EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Read the executive summary in Arabic (عربي) here and in Amharic (አማርኛ) here.

By 2022, the exploitation of social media platforms by malevolent actors has been documented extensively. In Western contexts, the dichotomy is seen as extremist actors exploiting social media platforms, such as Telegram, on one hand and other societal or state actors largely using these platforms for beneficial, benign purposes on the other. In non-Western countries, however, it is often authoritarian state actors who are most prolific in spreading propaganda, including disinformation, due to their access to state resources and their desire to dominate the information landscape. Our understandings still lag behind in comprehending which platforms are most important for which political communication in those environments. This is relevant since we recognize that propagandists are adaptive and rarely hold back from capitalizing on emerging technologies — and countries experiencing political transformations are more volatile to the effects of propaganda. Therefore, the Center for Media Engagement examined: How are encrypted messaging apps (EMAs) relevant for propagandists and/or activists in Egypt, Ethiopia, and Libya? How do these platforms fit into the existing (dis-)information landscape?

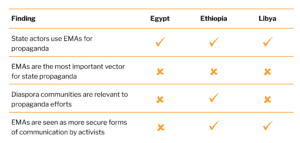

We found that:

- Key actors in all three countries use encrypted messaging apps (EMAs) as a medium for propaganda — combining them with the utilization of traditional social media, targeted internet shutdowns, and the mobilization of social media influencers and diaspora

- Yet EMAs also remain crucial for secure communication among activists in both Ethiopia and Libya in particular — two countries that benefit from the increased privacy of EMAs.

INTRODUCTION

In the Middle East and Africa, online space is often incorporated into power struggles and associated media manipulation efforts. 1 The resulting manipulation of public opinion triggered by these campaigns can be particularly potent in countries undergoing political transitions or repeated rounds of hostility and tumult after a revolution, such as in Libya. Generally, in Egypt, Ethiopia, and Libya, information ecosystems are defined by polarization as key actors aim to portray their often-belligerent actions and political visions as the only solution for the countries’ problems — ranging from corruption and poor socio-economic conditions in Egypt, to civil war in Ethiopia, and to divided authorities and reverberating insecurities in Libya.2 Previous studies have proven that propagandists are adaptive in their behavior and messaging.3 The Center for Media Engagement’s research focuses on encrypted messaging apps (EMAs) and their potential to be exploited for disinformation nurturing polarization. This report aims to contribute to a niche that is often neglected — how these more private platforms fit into existing (dis-)information landscapes.4

The utilization of EMAs, such as WhatsApp, Viber, or Telegram, for communication in Egypt, Ethiopia, and Libya is generally undisputed. WhatsApp is the most popular messaging app in Egypt, Viber has been widespread in Libya for several years, and Telegram has increased its penetration in Ethiopia significantly over the last several years.5 Furthermore, the political relevance of EMA usage in these countries surfaced in 2011 when WhatsApp was used to coordinate protests, especially within Egypt.6 However, due to the perceived novelty and reverberating surprise of the Arab revolts that year, the relevance of other, more open platforms quickly grabbed the attention of most analysts.7 It is clear from the resulting analysis that social media platforms like Facebook, YouTube, and Twitter are not only important for news consumption, but they also provide platforms for spreading misinformation and dangerous speech.8 The latter often lacks the local nuances complicating the designation of harmful content and the resulting difficulty for companies to deal with the spread adequately.9

What is unclear is whether EMAs are largely acting as facilitators of propaganda and disinformation10 due to their barely-existent content moderation, which could embolden actors to spread misleading messages with increased impunity, or whether EMAs simply facilitate a more open exchange between citizens that trust their encryption features and hence embark on exchanges removed from state censorship and surveillance. This report aims to provide insights into these questions that carry relevance for Egypt, Ethiopia, and Libya, as all three countries have undergone significant transformations recently and exhibit open revolt or simmering grievances that define parts of the population’s relation to state actors currently.11 In all three countries, citizens’ hopes and demands are largely disregarded in favor of the aims of self-serving actors such as the Egyptian Sisi regime; Ethiopian prime minister Abiy Ahmed and his close circle of confidants; and elites including Dbeiba, Bashaga, Saleh, and Haftar in West and East Libya.12

WHY THESE THREE COUNTRIES?

We selected the North African countries of Egypt and Libya as well as Ethiopia, located in the Horn of Africa, in order to explore the importance of EMAs in non-Western countries. Three research rationales drove this decision:

- Inter-case comparability based on recent history. All three countries have experienced political turmoil within the last ten years. In Egypt, protesters managed to topple the authoritarian government in 2011, but after the brief interval rule of a popular, Islamist president, the country is once again under authoritarian military rule.13 Ethiopia has been experiencing brief internal skirmishes but most significantly entered a locally focused war with Eritrea in the country’s Tigray region in the north.13 In Libya, revolutionaries violently overthrew eccentric dictator Muammar al-Gaddafi with international support in 2011 but since then the country has not found stability.14 These dynamics of profound political changes accompanied by uncertainty about the countries’ futures, for Libya and Ethiopia especially, lend themselves to a comparative analysis with Egypt, which has surpassed these instabilities by overpowering any challenge to its military leadership. With this case study selection, it is therefore possible to examine two non-Western political environments: chronic instability and military dictatorship. Further, we can compare differences in propaganda efforts in chronically unstable countries with the efforts of a country that has transitioned into a post-conflict, authoritarian phase.

- A track record of foreign interference in all three countries. Officials in these countries often decry foreign interference and regularly blame the countries’ problems on foreign meddling. While these interferences can be traced online, regional issues seem to overshadow Western online interference. Egypt and Libya share a 1,115 km long border and have been affected by each other’s political developments regularly.15 Ethiopia shares a 1,051 km long border with Eritrea — the two states were one country until 1952, before the nearly 30-year-long Eritrean War of Independence. In selecting these case studies, we aimed to contrast the cases and add to existing research that highlights the different levels of foreign, often regional, online interference and contrasts them.16

- Feedback from social media companies. Anonymous social media company representatives informed us prior to this research that these countries are of increasing concern for their platforms when it comes to the spread of disinformation, political propaganda, and the resulting violence, in part due to the issues we outlined above.

METHODOLOGY

Our team conducted 21 qualitative, semi-structured interviews across Egypt (6), Ethiopia (9), and Libya (6). Speaking to producers of disinformation in these countries proved particularly difficult due to skepticism of Western institutions, so to gain an understanding of the state of disinformation and the relevance of EMAs in the space, we interviewed regional experts and civil society members. Our interview subjects included fact-checkers (3), academics(4), journalists (3), disinformation researchers (6), community organizers (4), and a human rights lawyer (1). The three countries we selected are understudied by both academia and by social media platforms in comparison to Western countries, therefore the experiences of those on the ground in these countries are particularly important for understanding the disinformation landscapes.

Prior research from the Propaganda Research Lab at the Center for Media Engagement has found that EMAs are crucial vectors for propaganda and disinformation in the United States, Mexico, India, Brazil, Ukraine, and several Southeast Asian countries.17 Throughout these countries, EMAs have been utilized to spread disinformation in different ways.18 Scholars have even found that EMAs are the primary source of misinformation in Nigeria, India, and Pakistan, surpassing social and mainstream media.19 Concurrently, EMAs are also emerging or concretizing across various countries and communities as important spaces for democratic activism and dissent. Given this, we seek to answer two research questions related to the spread of propaganda over EMAs in Africa: How are EMAs relevant for propagandists and activists in Egypt, Ethiopia, and Libya? How do they fit into the existing (dis-)information landscape?

OVERVIEW OF FINDINGS

Collective Findings

- State propagandists are utilizing EMAs to spread political propaganda and disinformation. However, their propaganda efforts seem unsophisticated, indicating an ongoing learning process of how to best integrate EMAs into existing disinformation.

- State propagandists are fine-tuning the combinations of people and tools, such as bots, that act as their messengers online. Those who once relied solely on human labor to spread their content are now coming up with ways to automate its delivery and those who previously relied on cheap, rudimentary bots are deploying more advanced combinations of humans and bots, known as cyborg messengers.

- State propagandists are turning to new groups of people, including social media influencers and African diaspora communities in the West, to further spread their message.

Egypt

Egypt’s president, Abdulfattah El Sisi, and his military regime are preoccupied with warning citizens of an Islamist conspiracy aiming to take over the country, a message which has been a systematic and integral part of state propaganda.20 The popular win of a member of the Muslim Brotherhood in the country’s first fair election in 2012 shocked the military and the security apparatus, the foundational strength of Sisi’s regime. In 2022, however, the suppression by Sisi’s regime is so elevated that any real challenge to it is unfathomable.21 This is consistent with what our civil society interviewees emphasized. Overall, the relevance of EMAs in Egypt is three-fold:

- EMAs became integrated into a powerful authoritarian regime effort to control the country’s information landscape, with different ministries pursuing different approaches;

- Signal and Telegram gained popularity among activists, which is surprising due to their disparate levels of encryption.22 Most people are generally using WhatsApp for everyday communication;

- Trust in the safety and security of encryption is low, as people witness the totalitarian character of the Sisi regime regularly and hence believe the regime is able to infiltrate EMAs.

Ethiopia

In Ethiopia, a war between the Tigray Defense Force (TDF) and the Ethiopian government under Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed began in late 2020. In 2021, human rights abuses and atrocities were first reported in the Tigray region, which sits in the northern most corner of Ethiopia on the border with Eritrea.23 Hand-in-hand with this military confrontation, the media landscape has grown partisan, with individual journalists and news outlets touting either the Ethiopian government or the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF).24 Largely, this is a matter of survival in a contentious environment.25 We found three main dynamics concerning EMAs and propaganda in Ethiopia:

- Diaspora communities are connecting with people in the country via EMAs and are partially integrated into state propaganda efforts through pre-written, click-to-tweet campaigns organized by diaspora groups that spread support for the Ethiopian government;

- Internet shutdowns have unclear consequences on people’s opinions and mobilization via EMAs;

- Telegram has transcended WhatsApp as the most popular platform for the general population and has been rising in importance among activists. This increasing popularity seems less connected to the apps’ inherent security level, which remains low, and instead attached to perceptions that Telegram provides better, less biased information. The popularity is particularly tied to increased use by diaspora communities.

Libya

In Libya, the formation of a unity government under the umbrella of a United Nations-led negotiation process did not achieve anticipated successes. Instead, Libya in 2022 finds itself once again confronted with the prospect of two rival governments.26 Important to these political developments are parallel military and social interests, as individual politicians need to rely on military backing as well as popular support to convince Libyans to join their side — with Bashaga arguably betting on the former and Dbeiba on the latter.27 Embedded into this context of division, polarization, and bickering, we found three main dynamics concerning EMAs and propaganda in Libya:

- Propaganda is commonplace and escalates via social media when there are new political developments, such as a new military offensive;

- EMAs have been occasionally integrated into propaganda efforts targeting more open social media as well as traditional media due to their competitive advantage of being seen as platforms that are trusted messengers, as people largely connect with family and friends on them;

- There is a need for resources to address misinformation and propaganda on EMAs and other platforms, but an unfortunate mix of limited non-partisan local funding and Libya’s suspicions of foreign funding make addressing this gap difficult.

FULL FINDINGS

Polarization defines the information landscapes in Egypt, Ethiopia, and Libya. In addition, a lack of independent, well-funded media contributes to the proliferation of disinformation and propaganda as powerful actors that can manipulate information flow when employing resources to bolster their narratives. Disinformation is spreading on traditional social media platforms, but our research shows that propagandists seem to become more sophisticated as they aim to circumvent takedowns or content removal by, for example, switching between bots and human-controlled accounts in Libya or capitalizing on grassroots legitimization by taking advantage of diaspora communities and human-controlled accounts spreading favorable messaging in Ethiopia. Overall, EMAs are crucial vectors in this disinformation ecosystem as they allow for more private and hidden messaging that facilitates the two mentioned tactics. The following examines the similarities and differences in how Egypt, Ethiopia, and Libya utilize this trend.

Egypt

We found three main dynamics concerning EMAs and propaganda in Egypt: (1) EMAs become integrated in a powerful whole-of-regime effort to control the country’s information landscape. In this scenario, they are simply another vector incorporated into a powerful system of propaganda and suppression; (2) Facebook and WhatsApp are used most by state propagandists simply because they know these platforms best and are well-connected on them. With this, they further capitalize on macro-features that work in their favor: the prevalence of Facebook and WhatsApp usage by Egyptians; (3) Social media influencers (paid and unpaid) are experimenting with different forms of propaganda.

President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi has controlled Egypt with a strong authoritarian hand since seizing control in a coup in 2013. Heavy restrictions on civil liberties, such as the freedom of speech and assembly, have left many journalists, human rights defenders, and protesters imprisoned. 28 Legislation outlawing the spread of fake news on social media, paired with intolerance for expressions of government dissent, leaves no room for citizens to safely challenge the state. Freedom House rates Egypt as ‘Not Free.’29 The regime’s efforts ensure this situation includes online disinformation campaigns.30 The internet penetration rate in Egypt as of January 2022 was almost 72%, with over 75 million people in the country using the internet. 31 Facebook is widely used with over 44.70 million users throughout the country, accounting for over 60% of the total population.32 Overall, the internet has been incorporated as another repressive tool for the Egyptian government to further restrict free speech and government dissent.33 Internet shutdowns have persisted in Egypt’s history since the Arab Spring and politically-motivated new media legislations have allowed for government control of information.34

1. EMAs as Part of the State-Dominated Information Ecosystem

Access to unbiased information in Egypt is complicated by the state’s influence over the media ecosystem. Government influence is fed throughout this media ecosystem, including on radio stations, TV stations, (online)newspapers, and magazines.35 Other media content, including social media, has been policed by the government since legislation passed to “control” fake news, and disinformation — under the rationale of protecting national security.28 As a result of these crackdowns, journalists and social media users have been jailed or exiled for spreading alleged fake news online. The government’s heavy control of the media landscape makes it difficult for the population to gain access to unbiased or unfiltered news.36 The controlled narratives on major news channels, evening TV shows, radio stations, and newspapers trickle onto Facebook, Twitter, and other social media sites and also land in private chat groups on WhatsApp. An internet researcher in Egypt37 explained,

“Considering how centralized Egypt’s government is, they never just focus on one platform. It is a sort of ecosystem approach. When you see campaigns that are happening on Twitter, they are also happening on Facebook as well. They’re also related to what is happening on the nighttime news talk shows. There is also the same narrative that’s happening in the newspapers.”

In this way, government-sponsored information floods the entire media ecosystem. Journalists often self-censor due to fear of government violence or action, making unbiased information and news even scarcer. In this scenario, EMAs are simply another vector incorporated into a powerful system of propaganda and suppression.

2. Facebook and WhatsApp are Preferred Propaganda Outlets

As is the case in many countries across the globe, Facebook remains the dominant social media site in Egypt.38 But EMAs are also widely used for communication, with Telegram, WhatsApp, and Signal identified as the most popular three by our interviewees. According to them, it appears that WhatsApp is used for communication between family, friends, and neighbors, while activists and civil society groups tend to flock to Signal and Telegram for more secure communication. This is surprising, as WhatsApp offers end-to-end encryption (E2EE), while onTelegram, E2EE is only available for one-on-one chats. We learned that this distrust of, and exodus from, WhatsApp by people concerned with data privacy was due to a confusing message about WhatsApp’s data sharing policies with Facebook in 2021.39

Despite this, WhatsApp is heavily used for easy communication by Egyptians who are unconcerned with private messaging. Even so, Facebook remains the most prominent online platform for disinformation, according to the people we spoke with. According to our interviewees, the reasons for this are straightforward, namely that state employees in charge of spreading propaganda are most familiar with Facebook and — use WhatsApp regularly — and so pivot their efforts to these platforms. With this, they further capitalize on macro-features that work in their favor: the prevalence of Facebook and WhatsApp usage by Egyptians.

Furthermore, government officials capitalize on WhatsApp’s affordances in other ways. Government officials and journalists, who work for state-run media outlets, are connected through WhatsApp groups. A media researcher in Egypt explained that officials often utilize WhatsApp to distribute press releases to editors-in-chief from major newspapers throughout the country. The researcher explains,

“People joke, but it’s actually quite true that the [official] media landscape is operated out of a WhatsApp group and often times you will see, not just the exact same headline, but the exact same wording of an article in different newspapers.”

Planting identical narratives across media channels in this way is a well-established propaganda tactic that has been deployed by propagandists for years, as seen in the case of Russian propaganda.40 Controlling the media system gives the government the ability to gatekeep all news and information the public receives.

Finally, we were told by several of our interviewees that it is unlikely that the Egyptian government actively runs sophisticated and coordinated campaigns online simply because they don’t have to: “If the control is all newspapers and all platforms and all stations and all theaters and all schools and all curriculums and everything else, what’s the point of disinformation? You already control everything else…there’s no point pushing content if you control all the newspapers,” one disinformation researcher said. Consequently, this information also reaches WhatsApp. The state is likely not deploying specific disinformation tactics on EMAs in Egypt, our interviewees say, because the information spreads on its own. Given how much state content Egyptians come across on EMAs and the prosecutions of individuals for spreading “fake news,” trust in the safety formally attached to encryption is low.

3. Social Media Influencers are Experimenting Nationally and Regionally

On the other hand, our interviewees were adamant that online influencers in Egypt have grown their following for spreading propaganda. While it’s unclear who is behind these campaigns, it’s certainly possible that this is a new government tactic. Interviewees shared their observations of foreign actors spreading propaganda across the Middle East through the use of bots and through human-powered accounts. It is suspected that these campaigns are led by marketing firms hired to push content online. According to a researcher,

“Targeting would happen by flooding the internet with state-oriented traffic, and there have been various companies hiring content moderators and people who would draft and script and publish and handle many bots online or accounts online.”

At the same time, it would be simplistic to believe that all content in line with state messaging is paid for or created by paid state employees.

Existing information campaigns, also relying on influencers, have been detected already.41 Libya, a neighbor to powerful Egypt, especially suffered from influence operations coordinated by Egypt that aimed to prop up General Khalifa Haftar.42 Khalifa Haftar identified himself as the Libyan version of Egyptian president Abdelfattah El Sisi by emphasizing a counter terrorism agenda and general condemnation of Islamist groups. These aims are in accordance with Sisi’s political vision. Haftar became Egypt’s trusted partner and instilled hope to up security for the long border the two countries share.

Our sources recounted seeing content flow both ways: Egyptian-based accounts spreading pro-state propaganda in other regions as well as internationally-based accounts spreading propaganda in Egypt. Another disinformation researcher told us that the content was “very niche” and attempted to “shift public opinion about particular projects or economic issues (like projects with economic impact) … in one country or another.” They went on to describe specific observations of this strategy, “We were looking at the attempts to shore up domestic support versus the attempts to seemingly target Arabic speakers in other places. And so, there was a little bit of a spread in, not all networks did the same thing. Some appeared to be more like domestically focused, like writing for Egyptians to influence the domestic population, and others appeared to be outwardly focused, and just to kind of create discord among particular groups in the region.”These accounts are either real people or are sock puppet accounts or impostor of real people. One example involved the hijacking of an Eastern European athlete’s persona online where disinformation actors used the name of a real, established person to spread propaganda throughout the MENA region. Some of those we spoke to believed that these tactics are so heavily used by propagandists in Egypt that they have grown to rely on them. “There’s really a dependence on outsourced content,” said one analyst whose focus is on human rights.

Summary of Findings

The combination of the centralized nature of the regime-dominated media system in hand with the societal fear of Sisi’s apparatus makes for a polluted and confusing information environment in Egypt. There is an interesting, albeit disheartening dynamic we found when analyzing whether EMAs are relevant vectors for disinformation in Egypt — namely that the government’s hold on the media landscape is so strong that additional coordinated disinformation campaigns might not be necessary. However, existing research, as well as observations by our interviewees, found evidence of bot and human-powered disinformation campaigns across the region. Political frictions in the region have prompted foreign influence campaigns that make use of these tactics. While it is difficult to tie these campaigns explicitly to the Sisi government, it is clear that citizens of Egypt are inundated with state propaganda and EMAs, especially WhatsApp, largely facilitate this inundation.

Ethiopia

We found three main dynamics concerning EMAs and propaganda in Ethiopia: (1) Diaspora communities are connecting with people in the country via EMAs and are partially integrated into state propaganda efforts; (2)Internet shutdowns have unclear consequences on people’s opinions and mobilization via EMAs; (3)Telegram has transcended WhatsApp as the most popular platform for the general population and has been rising in importance among activists — this increasing popularity seems less connected to the apps’ lower inherent security level and instead attached to perceptions of Telegram as providing better, less-biased information.

Freedom House rates Ethiopia as “Not Free,” given the violence, political turmoil, and human rights abuses ongoing in the nation.43 Fighting between the Tigray Defense Force (TDF) and the Ethiopian government began in late 2020, and in 2021, human rights abuses and atrocities were reported in the Tigray region, which sits at the northernmost corner of Ethiopia, on the border with Eritrea. The disinformation and propaganda in these countries are thus imbricated, as Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed of Ethiopia, and President Isaias Afwerki of Eritrea only recently signed a peace agreement in 2018 after decades of conflict between the two countries.44 Now, they are allied over their shared goal of defeating the Tigrayans in the war on Tigray.45 Concurrently, the media landscape is partisan — with individual journalists and news outlets touting either the Ethiopian government or the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF). Largely, this is a matter of survival in a contentious environment. Given this overlap with Eritrea on the overshadowing political matter in Ethiopia, namely the war in Tigray, Eritrea also factored into our analysis.

Internet penetration in Ethiopia was at 25%, with just over 29 million people having access to the internet as of January 2022. Eritrea has just over 290,000 internet users, accounting for 8% of the population.46 The Facebook penetration in Ethiopia is 7.6% of people over 13 (5.95 million users) as of January 2022, while Eritrea’s is only 0.3% (7,300 users). Despite this, “Facebook is the internet” was a constant refrain in our interviews.47 Our interviewees did not believe that Facebook is doing enough to counter the widespread disinformation and propaganda on the platform: “Facebook makes a lot of money trying to be the internet in these emerging economies…But they do not invest the same amount of human capital and money into these markets,” the human rights lawyer told us.

1. State Propaganda and Diaspora Communities

Most of the disinformation and propaganda in Ethiopia and Eritrea is related to the war in Tigray, a fact-checker told us. The human rights lawyer we spoke with echoed this sentiment:

“There’s just no space for a neutral voice or an objective voice in this media climate and social media climate at all.”

This was reiterated by an Eritrean Ph.D. candidate, “Those of us from the horn….. in general, our political stance is either pro or anti-TPLF, being that they’re like the major floating signifier here,” she said.“Those who are pro will believe absolutely anything and those who are not will not believe anything.” A researcher shared that misinformation, disinformation, and conspiracy theories about both sides abound, “There’s a very strong and prominent narrative within pro-government groups, now within the ecosystem in general, of the TPLF having seeded the international diaspora, including refugees, with disinformation operatives or potentially actually violent operatives who are gonna be rebels later on down the line.” The Eritrean researcher we spoke to echoed this narrative, “TPLF-ites have a huge lobby power, they have a lot of money. It is under the impression of many, including myself, that they are in the pockets of different international media channels.” Whether true or not, this demonstrates that there is a persistent disconnect between the international news about the war and what Ethiopians and Eritreans are hearing on the ground. This is reinforced due to the locally polarized information landscape in these countries that pits journalists against each other as they are seeking to thrive, or at least survive in their respective areas.

Additionally, state propaganda seems to be increasingly trying to incorporate the diaspora. Interviewees told us about the disinformation campaigns that target or are started by Ethiopian diaspora groups and communities abroad; about the use of humans rather than automation for these campaigns (notoriously more difficult to catch); and about the emerging use of encrypted messaging apps, especially Telegram, for disinformation and propaganda. A journalist we spoke to highlighted the difficulty in controlling this content: “The diaspora had a really, really big role … and still does have are ally big role in spreading narratives. I’ve spoken with a couple of the diaspora groups … and they’ve all said that they are connecting with community members within the diaspora … and showing them how to make a Twitter account and then using the prewritten click-to-tweet campaigns.” She continued, saying it’s “kind of a grey area … because they are influencing a narrative by encouraging people to use a hashtag, but then it’s also like, activism.” Limiting this content is challenging, as sharing political messaging on Twitter is not necessarily problematic. However, this becomes worrying when there are large-scale click-to-tweet campaigns that spread disinformation or propaganda about the war.

2. Internet shutdowns and potentially unintended consequences

Both countries are plagued by government internet shutdowns, poor media literacy, and a lack of independent news, making it extremely challenging to decipher what information is true and what is false. When violence breaks out, the Ethiopian government is known to simply shut down the internet, another fact-checker informed us.48 When the internet is available, it’s a mess of misinformation, disinformation, and propaganda. We learned that especially in Eritrea, the internet connection is spotty at best and the media is entirely state- controlled. An Ethiopian fact-checker told us that independent Ethiopian media outlets have been forced to close, not because of the government, but because of the loss of revenue: “The audience has shifted to social media.”

This makes internet shutdowns all the more problematic, as they completely cut the population off from information. Another fact-checker relayed that because the media literacy is so low,

“It’s easy to manipulate and deceive people through just a simple photoshop.”

The human rights lawyer agreed: “You’ll see fake photos of a church burning or something and people will really believe it’s happening,” she said. “People are quick to mobilize around it.” This is something we heard repeatedly throughout our interviews: fake photos and videos, or photos and videos taken out of context, are particularly successful for spreading disinformation within Ethiopia. Finally, internet shutdowns seem to lead to potential heightened offline mobilization. As one local academic explained: “On the one hand, it limits coordination capabilities (…) [but it also] drives everyone in the streets because they have no other option. And (…) in Ethiopia(…) [internet shutdowns] increased (…) protests, not decreased it.”

3. Telegram is on the rise and brings with it hopes and fears

The human rights lawyer we spoke with shared that activists are relying more and more on Telegram. Already, she said, “things fly over WhatsApp really quick,” but according to our interviewees, and supported by data, WhatsApp has lost its number one spot to Telegram in Ethiopia.49 A fact-checker told us that, though it’s very difficult to fact-check,

“Telegram is widely used as a social source of information.”

Telegram, we learned, has become a space for gathering “real news,” engaging in activism, and also for spreading disinformation and propaganda. The lawyer we spoke with said that, “people generally do not feel comfortable mobilizing on WhatsApp or Facebook.” Two fact- checkers agreed, saying that WhatsApp is generally used for work, while Telegram is more popular and used for social engagement. Among some, there is a belief that identity is not tied to it.

Surprisingly, activists feel more comfortable on Telegram than on WhatsApp, given WhatsApp’s much strong encryption (as previously mentioned, Telegram does not offer E2EE for group chats, and E2EE must be manually selected by choosing “Secret Chats”). A journalist told us that Ethiopian diaspora communities tend to use WhatsApp, but we heard from an Ethiopian researcher that as the Ethiopian diaspora communities in the UnitedStates and the Middle East have begun to download Telegram more, domestic use has grown too. This, in combination with the fact that it’s cheaper since it requires less data,49 and since it is used by the news media, has caused Telegram to rise in popularity. As for political propaganda, the journalist we spoke with said that she was on some Telegram channels where they shared images of military personnel, which is concerning given what we know about the use of images to disseminate propaganda and manipulate the Ethiopian population. Our interviewees expressed just how difficult it is to monitor Telegram, a feat nearly impossible if you don’t speak Amharic. Despite this, many believe the government is actively supporting disinformation campaigns in these spaces. As disinformation flows through diaspora communities and diaspora communities increasingly adopt Telegram, our research indicates that it is likely that propaganda and disinformation will also increase on those platforms. Telegram, in particular, is a platform to watch.

Summary of Findings

The war in Tigray is affecting all of Ethiopia as well as parts of Eritrea due to its resource intensity and the conflict’s repercussions — most significantly the effect on food prices.50 Unfortunately, EMAs have largely shown to be incorporated into a polarized system where only one side is allowed to be right. However, Telegram has especially grown in importance with activists who try to exchange unbiased information and create (relatively) safe spaces away from the government’s prying eyes and propaganda machines. One of the most prevalent dynamics concerning EMAs, Ethiopia, and propaganda is the role of the diaspora community — this is an area to watch as the conflict drags on. A settlement might be necessary soon, however, due to increased pressure from the U.S.51

Libya

We found three main dynamics concerning EMAs and propaganda in Libya: (1) Propaganda is commonplace and upticks via social media have been linked to political developments, such as a new military offensive; (2) EMAs have been occasionally tied to propaganda efforts targeting more open social media, as well as traditional media, due to their competitive advantage of being seen as platforms comprised of trusted messengers, as people usually connect largely with family and friends on them; and (3) There is a need for resources to address misinformation and propaganda on EMAs and other platforms, but an unfortunate mix of little, non-partisan local funding and Libyan suspicions of foreign funding make addressing this gap difficult.

Libya’s political landscape in 2022 is marked by internal polarization and divisions stemming back to the 2011 uprising which deposed dictator Mu’ammar al-Gaddafi. In the decade since Gaddafi’s overthrow, hundreds of thousands of people have been displaced by violence as militias, often with foreign backers, vie for control of the country’s political system.52 In March 2021, international efforts helped bring Libya’s two rival administrations— the Government of National Accord (GNA) based in Tripoli and in control of much of western Libya, and the interim government affiliated with the House of Representatives (HoR) operating out of the East — together to form a precarious unity government (the Government of National Unity, GNU). According to Freedom House, Libya was rated as partly free in 2021, but internet freedom in the country had declined as local authorities throttled mobile service during protests over government corruption and living conditions in the country.53 As of January 2022, there were 3.47 million internet users in Libya, accounting for almost 50% country’s population of 7 million people.54 Notably, the number of Facebook users in the country was nearly 5.5 million,54 emphasizing the importance of the platform in daily life.

1. Propaganda is commonplace and ebbs and flows with political developments

Without a well-funded independent media, Libya’s media landscape has become increasingly factionalized in recent years depending on where different outlets are located.55 One of our interviewees, a community organizer, explained more broadly:

“Very few things in life in Libya are apolitical (…) in terms of media, and information and reporting, that is one institution in the country that is openly political and openly affiliated with various groups because of funding sources.”

Media outlets often report on the same events, but frame them in a way that is sympathetic to their cause, blurring the line between what is true and what is not. This change, however, has, in part, stemmed from demand from the public. “The change wasn’t in the media, but in the viewer,” said a former journalist who worked with DW in Libya. Our interviewees said that news consumers in Libya largely live in echo chambers when it comes to their news consumption — turning to outlets and news sources that affirm their already-held beliefs. This state of highly-political news has decreased the need to spread intentional disinformation on platforms. One researcher said that though much of the misleading information on platforms gets labeled as mis- or disinformation, it would be better categorized as propaganda since the facts themselves may be correct, but the framing and proportion are often distorted.

Efforts to correct distorted claims and disinformation are impeded by the lack of a centralized and trusted news media. “We don’t have reliable news,” said the former Libyan journalist. “Even if we had an official [news media],what is official? We have 2 governments: East and West.” This conflict between East and West is a central theme in the disinformation spread on platforms. Other issues, such as local conflicts, and, more recently, the presidential elections are also common. “Basic facts about the government are always contested in Libyan social media,” the researcher said. For example, rumors spread online about whether parliament is in session or whether a politician is still alive. False claims come from within Libya — from news organizations whose owners influence their content, and also from outside — from foreign actors who have a vested interest in the outcomes of Libya’s political conflicts. Twitter and Facebook takedown reports have shown content targeted at Libyan audiences from foreign actors in the United Arab Emirates, Morocco, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Turkey, Russia, and Iran.56 Accounts spreading disinformation sometimes rely on cultural values such as respect for elders by using images of older, bearded men in their profiles to lend a sense of authority to their claims, a community organizer told us.

2. EMAs as a space of exploration for propaganda

Facebook use is widespread in the country57 and remains the most popular platform for news consumption among Libyan citizens because they trust information consumed on social media more than the information coming from news outlets, interviewees said. However, the platform is also rife with misinformation. Unfortunately, the company is relatively slow to respond when false claims are made on the site since it is still lagging in its Arabic natural language processing. These issues raise concerns for one fact-checker, who said that people consuming information on the platform assume “if it’s on Facebook, it’s true.” Disinformation on the platform became more sophisticated after the 2019 invasion of Tripoli, he said, when actors began using bots on Twitter and Facebook to amplify content. Some accounts have also turned to a cyborg approach, using a combination of automation like schedulers and bots at times, but also turning to humans to interact with the users who engage with their content. The researcher told us,

“They’re coming up with different arguments, they’re responding, they’re engaging.”

Interviewees told us this change has coincided with an increase in dangerous speech and harassment, especially toward women and activists on the platforms — an issue exemplified by the harassment of prominent women rights activist and politician Siham Sergiwa in the days leading up to her violent abduction in 2019.58

Though WhatsApp and Viber are widely used by the general public for personal messaging, their increased security levels due to E2EE, for example, are not the reason EMAs have been widely adopted, according to our interviewees.WhatsApp, along with Facebook Messenger, has become widespread in part because it works well in areas with poor internet connection. Though the bulk of Libyan misinformation seems to spread on open platforms like Facebook and Twitter, one interviewee said there has been an increase in misinformation jumping from encrypted chat applications to those platforms. Claims spread in these closed spaces are often perceived as credible because they originate from a “trusted messenger” such as a relative or close friend, which leads them to spread from person to person, the researcher said. Telegram, Viber, and Signal are popular with groups and individuals who have increased security concerns, such as activists and members of militant political groups.

3. The Need for More Local Resources

Though fact-checking organizations have sprung up in the country to address growing concerns over the rampant disinformation and propaganda spreading across platforms in recent years, their efforts are stymied by a lack of resources and an unreceptive public. The fact-checker we spoke with said that fact-checkers like himself struggle to keep up with the barrage of claims because of a lack of funding and manpower. His organization, for example, is only able to address one to two claims per day, which barely scratches the surface of claims circulating online. Another major issue facing these organizations comes from their funding sources. With few resources available for such work within Libya, many fact- checking organizations rely on Western organizations for funding and training. The former journalist told us,

“We see any foreigner as spies … We have trust issues.”

This general distrust of foreign actors creates a difficult path for fact-checkers trying to address false claims online because they’re seen as another form of foreign interference in Libyan life.

Summary of Findings

The combination of ongoing divisions in the country and of regular military flare-ups affects the information environment as different actors are keen to establish the righteousness of their actions.

Our analysis suggests that Libya’s information ecosystem will likely continue along the same fractured path in the future. Interviewees expressed specific concerns about disinformation increasing as time draws closer to potential. presidential elections in 2022, which were postponed from December 2021. “If [the election] gets postponed again, from a disinfo point of view, that’s a terrible setback because it will just create even more chances for more rumors to spread,” the researcher said.

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

In sum, our analysis supports existing research that argues that much of the propaganda, including disinformation, in Egypt, Ethiopia, and Libya is rooted in the political turmoil that exists throughout the region.59 Turbulent regional conflicts have inspired propagandists to focus on this political unrest, capitalizing on the existing cleavages and tensions within the countries. Disinformation is coming from all three governments, as well as from outside the countries — such as from diaspora groups or other foreign actors, like Egyptian propagandists for hire, who are targeting Libya. Our interviewees in Ethiopia told us that the Ethiopian government is working on starting their own social media platform, which would presumably be full of pro-government and anti-TPLF messaging, which would likely lead to increased disinformation from the TPLF as well. EMAs are likely to continue to be manipulated for the spread of misinformation, disinformation, and propaganda and their popularity, combined with their characterization as a trusted messenger platform, makes them attractive avenues for propagandists to target.

Overall, it is necessary to invest more time and resources in researching and developing counter mechanisms for propaganda both on platforms, like Facebook and Twitter, and on more private ones like EMAs. Especially with authoritarian countries like Egypt, it is important to emphasize the existing legislative infringements on people’s human rights online as the laws target freedom of speech and also prohibit using encryption-based services, presumably under the rationale of protecting national security.60 Western- based social media platforms should enhance their existing responsibilities given their crucial position as tools for communication and sources of information in non-Western, less free countries. Investing resources to understand how social media, including EMAs, contributes to political polarization might seem arduous but if society as a whole, and not just regime allies, is supposed to benefit, social media companies should strive for better understandings of their platforms’ impacts in the Global South.

Many local activists emphasized that they often feel unheard and never feel like they have a seat at the table when it comes to decision-making by major social media companies. Frustratingly, propaganda and disinformation are more harmful more quickly in countries exhibiting political division or experiencing civil wars — both of which are overwhelmingly present in countries of the Global South, not the West.61 Many of our interviewees are not optimistic that social media sites will allocate sufficient resources to tackle this problem. “[They are] American companies with international reach, and they don’t really care about that last part,” says a lawyer from Ethiopia.

The findings of our report lead to three suggestions:

- Collaborating with locally-based civil society groups throughout the MENA region would provide the necessary resources to mitigate disinformation in these regions, both through earning credibility with locals, as well as through improving the accuracy of the companies’ language-processing abilities.62 Local populations should be involved in developing solutions if real effects are to be seen on the ground in North Africa and in the Horn of Africa.

- EMAs play a role in enhancing disinformation campaigns across the globe, and company representatives would be well-advised to draw up mid- to long-term strategies about how to take on responsible policies in different contexts — not just ad-hoc policies like those adopted after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Most important with regard to EMAs is balancing the protection of civil society activists with the combatting of exploitation for disinformation purposes.

- Supporting (1) and (2), platforms would need to invest additional resources, not only into quantitatively increased and qualitatively more nuanced content moderation, but also into understanding local contexts and consulting non- Western communities when rolling out new features for their platforms.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Sahar Khamis for providing extensive feedback on previous versions of this paper. Thank you to Alexandra Whitlock, Mirya Dila, and Emily Flores for their diligent research. This study is a project of the Center forMedia Engagement (CME) at The University of Texas at Austin and is supported by the Open Society Foundations, Omidyar Network, The Miami Foundation, and the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the funding bodies.

SUGGESTED CITATION:

Trauthig, I. K., Glover, K., Martin, Z., Goodwin, A., and Woolley, S. (August 2022). Polarized information ecosystems and encrypted messaging apps: Insights into Egypt, Ethiopia, and Libya. Center for Media Engagement. https://mediaengagement.org/research/polarized-information-ecosystems-and- encrypted-messaging-apps

- Banaji, Shakuntala, and Cristina Moreno-Almeida. (2021). Politicizing participatory culture at the margins: The significance of class, gender and online media for the practices of youth networks in the MENA region. Global Media and Communication 17.1: 121-142; Bassil, Noah, and Nourhan Kassem. (2021). The subtle dynamics of power struggles in Tunisia: Local media since the Arab Uprisings. Media and Communication 9.4: 286-296; Bradshaw, Samantha, and Philip N. Howard. (2019). The global disinformation order: 2019 global inventory of organised social media manipulation; Hinnebusch, Raymond. (2018). Understanding regime divergence in the post- uprising Arab states. Journal of Historical Sociology 31.1: 39-52; Yilma, Kinfe Micheal. (2021). On Disinformation, Elections and Ethiopian Law. Journal of African Law 65.3 (2021): 351-375.[↩]

- Egypt: Freedom in the World 2022 Country Report. (n.d.). Freedom House. Retrieved May 16, 2022, from https://freedomhouse.org/country/egypt/freedom-world/2022; Ethiopia: Freedom in the World 2022 Country Report. (n.d.). Freedom House. Retrieved May 6, 2022, from https://freedomhouse.org/country/ethiopia/freedom- world/2022; Libya: Freedom in the World 2022 Country Report. (n.d.). Freedom House. Retrieved May 16, 2022, from https://freedomhouse.org/country/libya/freedom-world/2022; Tahrir Institute for Middle East Policy. (2019, October 23). TIMEP Brief: Export of Surveillance to MENA Countries.TIMEP. https://timep.org/reports-briefings/ timep-brief-export-of-surveillance-to-mena-countries/.[↩]

- Porter, Hannah. (2022). Propaganda, Creativity, and Diplomacy: The Huthi’s Adaptive Approach to Media and Public Messaging. The Huthi Movement in Yemen: Ideology, Ambition and Security in the Arab Gulf.[↩]

- Ncube, Lyton. (2019). Digital media, fake news and pro-Movement for Democratic Change (MDC) alliance cyber- Propaganda during the 2018 Zimbabwe election. African Journalism Studies 40.4 (2019): 44-61.[↩]

- Dallal, Alina. (2022, Nay 18). Most Popular Messaging Apps Around the Globe. Similar Web. https://www.similarweb.com/corp/blog/research/market-research/worldwide-messaging-apps/; Orpaz, Inpal (2016, June 22). The Israeli Answer to WhatsApp Is Big in Eastern Europe – and Iraq. Haaretz. https://www.haaretz.com/israel- news/business/2016-06-22/ty-article/.premium/the-whatsapp-of-greece-ukraine-and-iraq/0000017f-e056-df7c- a5ff-e27eb7a80000; Dahir, A. L. (2018, February 23). In a continent dominated by WhatsApp, Ethiopia prefers Telegram. Quartz. https://qz.com/africa/1214381/in-a-continent-dominated-by-whatsapp-ethiopia-says-yes-to- telegram/.[↩]

- Gerbaudo, Paolo, and Emiliano Treré. (2015). “In search of the ‘we’ of social media activism: introduction to the special issue on social media and protest identities.” Information, communication & society 18.8 (2015): 865-871.[↩]

- Al-Jenaibi, Badreya. (2014). The nature of Arab public discourse: social media and the ‘Arab Spring’. Journal of Applied Journalism & Media Studies 3.2 (2014): 241-260; Comunello, Francesca, and Giuseppe Anzera. (2012). Will the revolution be tweeted? A conceptual framework for understanding the social media and the Arab Spring. Islam and Christian–Muslim Relations 23.4 (2012):453-470; Wolfsfeld, Gadi, Elad Segev, and Tamir Sheafer. Social media and the Arab Spring: Politics comes first. The International Journal of Press/Politics 18.2 (2013): 115-137.[↩]

- Bicher, Lama, and Shrook A Fathy. (2021). Infodemic and Digital Literacy: The Role of Digital Literacy in Combating Misinformation of COVID-19 on Facebook. ةلجملا ةيبرعلا ثوحبل مالعالا لاصتالاو 2021.31; Pourghomi, Pardis, Milan Dordevic, and Fadi Safieddine. (2020). Facebook fake profile identification: technical and ethical considerations. International Journal of Pervasive Computing and Communications; Srinivasan, Ramesh. (2014). What Tahrir Square has done for social media: A 2012 snapshot in the struggle for political power in Egypt. The Information Society 30.1: 71-80.[↩]

- Shackelford, S. (2020, November 2). How tech firms have tried to stop disinformation and voter intimidation – and come up short.The Conversation. http://theconversation.com/how-tech-firms-have-tried-to-stop-disinformation- and-voter-intimidation-and-come-up-short-148771.[↩]

- This follows Derakhshan and Wardle (2017), who define propaganda as “true or false information spread to persuade an audience,(that) often has a political connotation and is often connected to information produced by governments.” Derakhshan, H., & Wardle, C. (2017). Information disorder: definitions. AA. VV., Understanding and addressing the disinformation ecosystem, 5-12. Derakhshan, H., & Wardle, C. (2017). Information disorder: definitions. AA. VV., Understanding and addressing the disinformation ecosystem, 5-12. And also Wardle and Derakhshan‘s definitions of misinformation and disinformation: disinformation is“information that is false and deliberately created to harm a person, social group, organization or country;” misinformation is“information that is false, but not created with the intention of causing harm;” malinformation is “information that is based on reality, used to inflict harm on a person, organization or country.” Wardle, C., & Derakhshan, H. (2017). Information disorder: Toward an interdisciplinary framework for research and policy making. Council of Europe, 27, 20.[↩]

- Arriola, Leonardo R. (2013). Protesting and policing in a multiethnic authoritarian state: evidence from Ethiopia. Comparative Politics 45.2 (2013): 147-168; Barakat, Zahraa, and Ali Fakih. (2021). Determinants of the Arab Spring Protests in Tunisia, Egypt, and Libya:What Have We Learned? Social Sciences 10.8 (2021): 282; Trauthig, Inga Kristina. (2019). Assessing the Islamic State in Libya: The current situation in Libya and its implications for the terrorism threat in Europe. EUROPOL.[↩]

- Lynch, J. (2022, June 29). Iron Net: Digital Repression in the Middle East and North Africa. ECFR. https://ecfr.eu/publication/iron-net-digital-repression-in-the-middle-east-and-north-africa/; Tasci, Ufuk Necat. (2022, April 27). Libya’s power struggle and the politics of oil. The New Arab. https://english.alaraby.co.uk/analysis/libyas-power- struggle-and-politics-oil.[↩]

- Housden, Oliver. 2013. Egypt: Coup d’Etat or a Revolution Protected? The RUSI Journal 158.5: 72-78. APA[↩][↩]

- Trauthig, Inga Kristina and Lukas Kupfernagel. 2022, March 22. Libya’s Leadership Chaos: About Failed Elections and Shifting Alliances. Al Sharq Forum. https://research.sharqforum.org/2022/03/15/libyas-leadership-chaos/.[↩]

- Tamara Cofmann-Wittess. 2020. Egypt: Trends, politics, and human rights. Brookings Institution. https://www.brookings.edu/testimonies/egypt-trends-politics-and-human-rights/.[↩]

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies. (2022, April 26). Mapping Disinformation in Africa. Africa Center for Strategic Studies.https://africacenter.org/spotlight/mapping-disinformation-in-africa-russia-china/; Africa Center for Strategic Studies. (2020, October 9). A Light in Libya’s Fog of Disinformation – Africa Center. Africa Center for Strategic Studies. https://africacenter.org/spotlight/light-libya-fog-disinformation/.[↩]

- Gursky, J., Glover, K., Joseff, K., Riedl, M. J., Pinzon, J., Geller, R., & Woolley, S. C. (2020). Encrypted Propaganda: Political Manipulation Via Encrypted Messaging Apps in the United States, India, and Mexico. Center for Media Engagement. https://mediaengagement.org/research/encrypted-propaganda/; Martin, Z., Glover, K., Trauthig, I. K., Whitlock, A., & Woolley, S. C. (2021). Political Talk in Private: Encrypted Messaging Apps In Southeast Asia and Eastern Europe. Center for Media Engagement. https://mediaengagement.org/research/encrypted-messaging- apps-in-southeast-asia-and-eastern-europe/; Trauthig, I. K., & Woolley, S. C. (2022, March). Escaping the Mainstream? Pitfalls and Opportunities of Encrypted Messaging Apps and Diaspora Communities in the U.S. Center for Media Engagement. https://mediaengagement.org/research/encrypted-messaging-apps-and-diasporas/.[↩]

- Bandeira, L., Barojan, D., Braga, R., Peñarredonda, J. L., & Argüello, M. F. P. (2019). Disinformation in democracies: Strengthening digital resilience in Latin America. Atlantic Council.; Banaji, S., Bhat, R., Agarwal, A., Passanha, N., & Sadhana Pravin, M. (2019). WhatsApp vigilantes: An exploration of citizen reception and circulation of WhatsApp misinformation linked to mob violence in India.Department of Media and Communications, London School of Economics and Political Science, London, UK; Dias, N. (2017, August 17). The Era of Whatsapp Propaganda Is Upon Us. Foreign Policy. https://foreignpolicy.com/2017/08/17/the-era-of-whatsapp-propaganda- is-upon-us/; Evangelista, R., & Bruno, F. (2019). WhatsApp and political instability in Brazil: Targeted messages and political radicalisation. Internet Policy Review,8(4), 1-23.; Pasquetto, I. V., Jahani, E., Baranovsky, A., & Baum, M. A. (2020). Understanding misinformation on mobile instant messengers (MIMs) in developing countries. Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics, and Public Policy. https://www.shorensteincenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/ Misinfo-on-MIMs-Shorenstein-Center-May-2020.pdf.[↩]

- Pasquetto, I. V., Jahani, E., Baranovsky, A., & Baum, M. A. (2020). Misinformation on Mobile Instant Messengers (MIMs) in Developing Countries (p. 27). Shorenstein Center.[↩]

- Brown, Nathan J., and Michele Durocher Dunne. (2019). Unprecedented pressures, uncharted course for Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood. Vol. 29. Washington, DC: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 2015; Pratt, Nicola, and Dina Rezk. Securitizing the Muslim Brotherhood: State violence and authoritarianism in Egypt after the Arab Spring. Security Dialogue 50.3 (2019): 239-256. For a valuable overview also see: https://journalistsresource.org/ economics/research-arab-spring-internet-key-studies/.[↩]

- Edel, Mirjam, and Maria Josua. (2018). How authoritarian rulers seek to legitimize repression: framing mass killings in Egypt and Uzbekistan. Democratization 25.5: 882-900; Grimm, Jannis, and Cilja Haders. (2018). Unpacking the effects of repression: The evolution of Islamist repertoires of contention in Egypt after the fall of President Morsi. Social Movement Studies 17.1: 1-18; Koehler, Kevin. (2016). “Don’t Listen to Anyone But Me! Will al-Sisi Consolidate Military Rule in Egypt?.” Florence: Mediterranean Research Meeting.[↩]

- Users must manually turn on end-to-end encryption (E2EE) on Telegram, and this feature is unavailable for group chats, as opposed to WhatsApp and Signal, which both offer E2EE. Greenberg, A. (2021, January 27). Fleeing WhatsApp for Better Privacy? Don’t Turn to Telegram. Wired. https://www.wired.com/story/telegram-encryption- whatsapp-settings/.[↩]

- Abai, Mulugeta. (2021). War in Tigray and Crimes of International Law.” First Light–A Publication of the Canadian Centre for Victims of Torture. Bernal, Victoria (2006). Diaspora, cyberspace and political imagination: the Eritrean diaspora online, Global Networks, 6.2:161-179.[↩]

- Fisher, Jonathan. (2022). #HandsoffEthiopia: ‘Partiality’, Polarization and Ethiopia’s Tigray Conflict.” Global Responsibility to Protect 14.1: 28-32; Wilmot, Claire, Ellen Tveteraas, and Alexi Drew. (2021). Dueling information campaigns: The war over the narrative inTigray. The Media Manipulation Casebook 20.[↩]

- Wilson, S. L., Lindberg, S., & Tronvoll, K. (2021). The best and worst of times: The paradox of social media and Ethiopian politics. First Monday, 26(10). https://firstmonday.org/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/10862; Knight, Tessa. (2021, December 17). Influential Ethiopian social media accounts stoke violence along ethnic lines. DRFLab. https://medium.com/dfrlab/influential-ethiopian-social-media-accounts-stoke-violence-along-ethnic-lines-6713a1920b02.[↩]

- Assad, Abdulkader. (2022, June 18). Al-Namroush supports neither Dbeibah nor Bashagha, aims to keep Tripoli away from conflicts. Libya Observer. https://www.libyaobserver.ly/news/al-namroush-supports-neither-dbeibah- nor-bashagha-aims-keep-tripoli-away-conflicts.[↩]

- Golden, Rabia. (2021, September 17). Dbeiba allocates the initial batch of funding from the “Marriage Support Fund.” Libya Observer. https://www.libyaobserver.ly/inbrief/dbeiba-allocates-initial-batch-funding-%E2%80%9Cmarriage-support-fund%E2%80%9D.[↩]

- Egypt: Freedom in the World 2022 Country Report. (n.d.). Freedom House. Retrieved May 16, 2022, from https://freedomhouse.org/country/egypt/freedom-world/2022.[↩][↩]

- Ibid[↩]

- Fekri, Amira. (2020, August 28). Egyptian officials try to co-opt social media influencers, spark doubts. The Arab Weekly.https://thearabweekly.com/egyptian-officials-try-co-opt-social-media-influencers-spark-doubts; Michaelsen, Ruth and Michael Safi. (2021, January 29). Sugar-coated propaganda? Middle East taps into power of influencers. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/jan/29/sugar-coated-propaganda-egypt- taps-into-power-instagram-influencers.[↩]

- Data Reportal. 2022. https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2022-egypt.[↩]

- Ibid.[↩]

- For a comparison on how Egyptian bloggers were able to at least provide a counter discourse in the past, see El- Nawawy, Mohammed, and Sahar Khamis. (2016). Egyptian revolution 2.0: Political blogging, civic engagement, and citizen journalism. Springer, 2016.[↩]

- Reuters (17 July 2018). Egypt targets social media with new law. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/article/us- egypt-politics/egypt-targets-social-media-with-new-law-idUSKBN1K722C.[↩]

- TIMEP Brief: Press Freedom in Egypt. 2022. https://timep.org/reports-briefings/timep-briefs/timep-brief-press- freedom-in-egypt/.[↩]

- Shea, Joey and Alexei Abrahams. (2020, October 26). Disinformation Wars in Egypt: The Inauthentic Battle on Twitter between Egyptian Government and Opposition. Just Security. https://www.justsecurity.org/72961/disinformation-wars-in-egypt-the-inauthentic-battle-on-twitter-between-egyptian-government-and-opposition/.[↩]

- All interviewees are referred to broadly by their role (i.e., journalist, activist, researcher, etc.) without identifying specifics as to their position, job title, company, etc. to protect the safety and privacy of interviewees, in line with University of Texas’ Institutional ReviewBoard-approved specifications.[↩]

- Statista. 2022. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1263755/social-media-users-by-platform-in-egypt/#:~:text=As%20of%20December%202021%2C%20Facebook,and%20close%20to%2015.9%20million%2C.[↩]

- Nast, C. (2021, July 24). All the data WhatsApp and Instagram send to Facebook. Wired UK. https://www.wired.co.uk/article/whatsapp-instagram-facebook-data; Newman, L. H. (2021, January 8). WhatsApp Has Shared Your Data WithFacebook for Years, Actually. Wired. https://www.wired.com/story/whatsapp-facebook-data-share- notification/.[↩]

- Abrams, S. (2016). Beyond Propaganda: Soviet Active Measures in Putin’s Russia. Connections: The Quarterly Journal. 15(1), 5-31.[↩]

- Michaelson, Ruth and Michael Safi. (2019, December 15). #Disinformation: the online threat to protest in the Middle East. TheGuardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/dec/15/disinformation-the-online-threat- to-protest-in-the-middle-east.[↩]

- Abrahams, A., & Shea, J. (2021, February 5). Coordinated Behavior in Libya’s Regional Disinformation Conflict. Lawfare. https://www.lawfareblog.com/coordinated-behavior-libyas-regional-disinformation-conflict.[↩]

- Ethiopia: Freedom in the World 2022 Country Report. (n.d.). Freedom House. Retrieved May 6, 2022, from https://freedomhouse.org/country/ethiopia/freedom-world/2022.[↩]

- Walsh, D., & Dahir, A. L. (2022, March 16). Why Is Ethiopia at War With Itself? The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/article/ethiopia-tigray-conflict-explained.html.[↩]

- Walsh, D. (2021, December 15). The Nobel Peace Prize That Paved the Way for War. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/12/15/world/africa/ethiopia-abiy-ahmed-nobel-war.html.[↩]

- Data Reportal. 2022. https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2022-ethiopia?rq=ethiopia; https://datareportal. com/reports/digital-2022-eritrea.[↩]

- Hao, K. (2021, November 20). How Facebook and Google fund global misinformation. MIT Technology Review. https://www.technologyreview.com/2021/11/20/1039076/facebook-google-disinformation-clickbait/; Rogers, A. (2018, January 25). You Can’t Trust Facebook’s Search for Trusted News. Wired. https://www.wired.com/story/ you-cant-trust-facebooks-search-for-trusted-news/; Mitchell, A., Jurkowitz, M., Oliphant, J. B., & Shearer, E. (2020, July 30). Americans Who Mainly Get Their News on Social Media Are Less Engaged, Less Knowledgeable. Pew Research Center’s Journalism Project.https://www.pewresearch.org/journalism/2020/07/30/americans-who- mainly-get-their-news-on-social-media-are-less-engaged-less-knowledgeable/.[↩]

- Hernandez, M. D., Nunes, R., Anthonio, F., & Cheng, S. (2021, June 7). #KeepItOn update: Who is shutting down the internet in2021? Access Now. https://www.accessnow.org/who-is-shutting-down-the-internet-in-2021/.[↩]

- Dahir, A. L. (2018, February 23). In a continent dominated by WhatsApp, Ethiopia prefers Telegram. Quartz. https://qz.com/africa/1214381/in-a-continent-dominated-by-whatsapp-ethiopia-says-yes-to-telegram/.[↩][↩]

- Macau Business. (2022, June 19). Abiy walks fine line in possible peace talks in Ethiopia. https://www.macaubusiness.com/abiy-walks-fine-line-in-possible-peace-talks-in-ethiopia/.[↩]

- Garrison, Ann. (2022, June 19). Democrats Not Only Game in Town for Ethiopian-American Voters. LAP Progressive.https://www.laprogressive.com/election-reform-campaigns/democrats-are-not-the-only-game-in- town.[↩]

- Libya: Freedom in the World 2022 Country Report. (n.d.). Freedom House. Retrieved May 16, 2022, from https://freedomhouse.org/country/libya/freedom-world/2022.[↩]

- For some recent reports by Meta see: https://about.fb.com/news/2020/12/removing-coordinated-inauthentic- behavior-france-russia/; https://about.fb.com/news/2019/10/removing-more-coordinated-inauthentic-behavior- from-russia/;https://about.fb.com/news/2019/08/cib-uae-egypt-saudi-arabia/.[↩]

- Data Reportal. 2022. https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2022-libya#:~:text=Data%20show%20that%20Libya’s%20population,percent%20lived%20in%20rural%20areas.[↩][↩]

- Wollenberg, Anja and Carola Richter. (2014). Political Parallelism in Transitional Media Systems: The Case of Libya. International Journal of Communication. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/12698.[↩]

- Borger, Julian. (2020, April 3). Twitter deletes 20,000 fake accounts linked to Saudi, Serbian and Egyptian governments. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2020/apr/02/twitter-accounts-deleted- linked-saudi-arabia-serbia-egypt-governments; for some recent reports and analysis see: https://fsi.stanford.edu/ content/oya-cluster-takedown;https://about.fb.com/news/2020/11/october-2020-cib-report/.[↩]

- Statista. 2022. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1284862/number-of-social-media-users-in-libya-by-platform/#:~:text=Number%20of%20social%20media%20users%20in%20Libya%202021%2C%20by%20platform&text=Facebook%20was%20the%20leading%20social,1.7%20million%20Libyans%20used%20Instagram.[↩]

- https://www.amnesty.org/en/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/MDE1950972021ENGLISH-1.pdf.[↩]

- For an overview of research on MENA see Leber, Andrew, and Alexei Abrahams. (2021, August). Social media manipulation in theMENA: Inauthenticity, Inequality, and Insecurity. Digital Activism and Authoritarian Adaptation in the Middle East, POMEPSStudies.[↩]

- Privacy International. (2019, January 26). State of Privacy Egypt. https://privacyinternational.org/state- privacy/1001/state-privacy-egypt.[↩]

- Allen, C. (2022, April 19). Facebook’s Content Moderation Failures in Ethiopia. Council on Foreign Relations.https://www.cfr.org/blog/facebooks-content-moderation-failures-ethiopia.[↩]

- Oliver, L. (2021, September 30). The fight for facts in the Global South: How four projects are building a new model. ReutersInstitute for the Study of Journalism.[↩]