ABSTRACT

Encrypted messaging applications (EMAs)1 such as Signal, Telegram, Viber, and WhatsApp have experienced a usership boom in recent years. This uptick in adoption, with WhatsApp growing its user base by over a billion from 2016 to 2020,2 has occurred for several reasons: EMAs are a free alternative to SMS texting, they offer secure communication, and they are an alternative to embattled ‘traditional’ social media platforms like Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube. But as EMA use skyrockets worldwide, political groups around the world are working to leverage them as tools for sowing propaganda and manipulating public opinion.

Over the last year, the Center for Media Engagement propaganda research team studied political manipulation on EMAs. Our analysis is focused on the production of influence operations in three countries: the U.S., India, and Mexico. We conducted 32 interviews with producers of EMA-based propaganda and experts on this phenomenon and combined insights from these interviews with an analysis of country-specific and global news coverage of EMAs, dis- and mis- information, and propaganda in order to identify trends in political usage of these apps.

INTRODUCTION

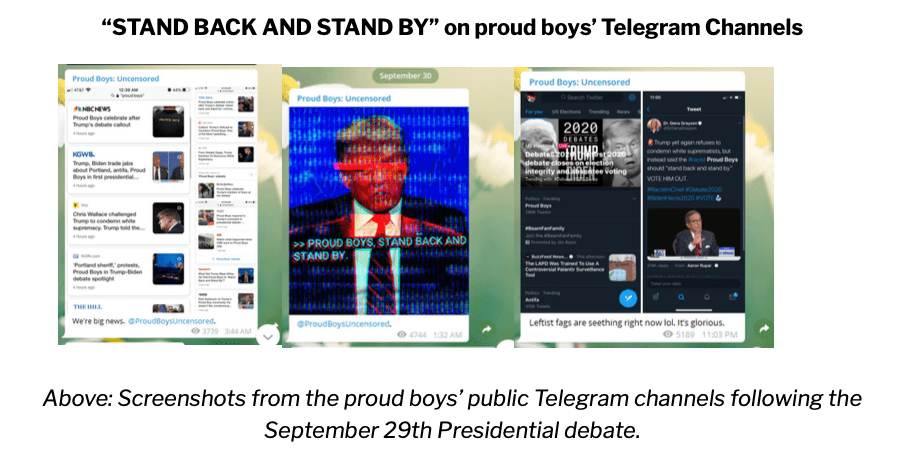

In the midst of the chaotic bickering of the first U.S. Presidential debate on September 29, 2020, Donald Trump called out to the well-known white supremacist group the proud boys. The moderator had asked President Trump to condemn such hate groups, many of which have offered support for his presidency.3 His response was, “Proud boys,4 stand back and stand by.” This call-to-action has been rapidly adopted by the organization’s online adherents as a slogan of sorts. On Telegram, an increasingly popular space for communication and organization amongst U.S. extremist groups,5 the group has begun using Trump’s comment as both an endorsement and a rallying cry.6

The proud boys used Telegram to proclaim a perceived ‘victory’ to staunch supporters, potential recruits, and internet users traveling down Presidential debate-fueled research rabbit holes. While often viewed as spaces used exclusively for private conversations, Telegram has an option for publicly accessible, large-scale, broadcast groups7 where one user can spread content to many others. In the case of extremist groups, these one-to-many messages offer a space where users that have been banned from other platforms can reach their networks.8 For such organizations, broadcasts can be used to funnel potential recruits into concentrically smaller and more hidden spaces, such as actual end-to-end (e2e) encrypted chats in Telegram.9 These public groups are accessible for researchers and others hoping to analyze communication on this particular portion of Telegram.10 In fact, anyone who looks up “proud boys” using Google after the first presidential debate could find and access their Telegram broadcasts.

In other circumstances, however, both extremist groups and mainstream political organizations use EMAs for their private communication capacity. For instance, these secure spaces can serve as useful incubators11 for designing disinformation campaigns intended to be amplified over publicly-accessible media—on Facebook, YouTube, and Reddit and amongst the broad ecosystem of media outlets—in networked propaganda efforts.12 Political actors around the globe are now using EMAs in attempts to rally their bases, recruit new members, broadcast party content, plan influence operations, share disinformation, and, ultimately, manipulate public opinion.

OUR RESEARCH

The Production Side of Propaganda on EMAs

To understand who designs, builds, and launches propaganda efforts on EMAs in the U.S., India, and Mexico, the Center for Media Engagement propaganda research team collected and analyzed instances in which EMAs were used to organize and/or disseminate coordinated influence operations. Through this process, we identified and cataloged 28 distinct cases of such EMA influence operations in India, 24 cases in Mexico, and 45 cases in the United States.13 We began our collection in fall 2019, but the cases themselves range from 2015 to 2020. Each country’s cases are divided by topic: elections, incitements of violence, and coronavirus-specific mis- and disinformation. Here we showcase some of these instances to illuminate country-specific strategies for the political use of EMAs and emerging international trends of a phenomenon we term encrypted propaganda.

Encrypted propaganda is a novel form of political manipulation that occurs over EMAs. It includes efforts to both sow disinformation and scale misinformation. Disinformation is defined as purposefully-spread false information, whereas misinformation is false information that is spread unintentionally or unknowingly.14 The term propaganda includes politically inclined versions of both, but also speaks to more general attempts by political groups to leverage communication tools in both veiled and overt efforts to affect peoples’ socio-political views and actions. Similarly, influence operations “describe efforts to influence a target audience, whether an individual leader, members of a decision-making group, military organizations and personnel, specific population subgroups, or mass publics.”15

Along with this case list, we have also conducted 32 interviews, primarily with people in each country who make and build propaganda campaigns on EMAs. We interviewed propagandists who work professionally or on a volunteer basis for political parties, governments, extremist groups, and other political entities. To enrich our understanding of their efforts—particularly in India and Mexico, where we have limited cultural and political understanding—we also spoke with journalists, researchers, marketing professionals, and digital political consultants.

We focused our attention on the U.S., India, and Mexico for several reasons. First, the U.S. and India are democracies that have shifted towards authoritarianism and populism in recent years.16 Mexico, meanwhile, is a democracy that has struggled with political corruption for decades.17 How might these countries’ political problems, and illiberal machinations be reflected in their political groups’ propagandistic use of EMAs? Each country is going through or has recently gone through, a competitive, contentious election. Social media plays a significant, ever-growing role in political communication across all three. Finally, EMA usage is diverse, in terms of penetration or reach, in all three countries. Take WhatsApp usage in each country: In the United States, 13% of internet users use the Facebook-owned EMA.18 In Mexico, approximately 76% of internet users use it.19 In India, there were over 400 million active users in 2019.20 Though this figure accounts for just 30 percent of the Indian population, it is larger than the total population of people living in either the U.S. or Mexico. India is, in fact, WhatsApp‘s largest market.21

EMAs: Trust, Secrecy, and Disinformation

Encrypted messaging applications are growing in popularity and amassing large active user bases. In India and Mexico, the popularity of EMAs (particularly WhatsApp) has increased in places where it is the most viable option for communication and developing an online presence. WhatsApp, in particular, provides incentives aimed at making adoption easy and feasible for new digital populations.22 Apps like WhatsApp23 and Telegram24 have become increasingly popular, although the convenience of the platform is often more important to adoption than an accurate understanding of the level of security provided.25 Nevertheless, content shared through EMAs is largely unmoderated by platforms, not to mention mostly private,26 making the tracking and correcting of disinformation and misinformation very difficult.

In the age of constant connectivity, propaganda–and the threat it poses to democracy– is amplified and accelerated.27 Discussions around the issue of “computational” or “network” propaganda have primarily revolved around platforms such as Facebook and Twitter, and broader “mainstream” media ecosystems. But EMAs have become increasingly important spaces in which propaganda thrives and spreads online. The central appeal of these platforms, for both users and for those seeking to manipulate them, is the ability to create relationally close-knit information silos. These more secure digital spaces are populated by anywhere from two to several hundred people who have a broader shared identity (e.g., Brazilian Americans based in Austin, Texas). Encrypted spaces are uniquely vulnerable because they require the development of specialized strategies to counter disinformation without compromising the security of a given platform.28

Trends in Political Usage of EMAs Across the U.S., India, and Mexico

Drawing on the case list and our interviews, there are several high-level trends in the ways in which encrypted messaging applications are impacting political discourse and decision making in the U.S., India, and Mexico:

- There are feedback loops between networks on encrypted platforms and politicians’ content on mainstream platforms, such as Twitter.

- In both the United States and India, the President and Prime Minister, respectively, have actively cultivated relationships with content creators and distributors who use EMAs to manipulate the mainstream media.29

- Offline violence tied to lies spread on EMAs has occurred.30

- In all three countries, violent and extremist individual organizations seek to use EMAs to stoke offline violence. In India and Mexico, there are particularly similar occurrences of rumors spread on EMAs leading to mob violence.31

- In all three countries, we see increasingly complex tactics for organizing disinformation campaigns.

- In the United States, alternative platforms are populated by radical groups that actively seek to get their message into the mainstream. Events like the White House Social Media Summit32 and the advent of “digital armies”33 in India seek to better capitalize on those relationships.

- In India, there are explicit government-coordinated disinformation campaigns conducted by “IT Cells” across WhatsApp. It is public knowledge that these cells often mass-share scripted content that has been approved by the Bharatiya Janata Party’s digital head.34

- EMAs do not follow international boundaries and thus allow for harmful information to flow across borders. For example, cartels in Mexico are able to harass their victims even after they have left the country by using WhatsApp.35 In the U. S., communities seeking to communicate internationally often rely on EMAs,36 as opposed to traditional SMS text messaging, because they allow for free and easy communication. Disinformation and radicalism have spread to the chats of these communities. International communities in Miami and Los Angeles have been particularly affected by this infiltration of harmful information.37

Country by Country Summary

United States

In the U.S., the creation of mis- and disinformation often happens in message boards like 4chan,38 alternative social media platforms like Gab,39 Mastodon,40 or Parler,41 and private groups in EMAs such as Discord42 and Telegram.43

- Alternative social media platforms, like Gab and Mastodon, are used by radical groups to spread hate speech that could potentially be regulated on mainstream social platforms.44 New trends indicate that radical groups are using video games, like Fortnite, to recruit members and further spread their ideology.45

- Disinformation pertaining to COVID-19 has spread anti-Asian sentiment, potentially dangerous fake “cures” for the virus, and conspiracy theories regarding the origin of the virus.46

- Disinformation is flourishing in EMAs used by several immigrant communities in the U.S., for instance in Latinx communities in Miami (on WhatsApp)47, or in Korean-American communities in Los Angeles (on KakaoTalk).48

As mentioned in our introduction, EMAs in the United States are often havens for actors who have been pushed off of Twitter, Facebook, YouTube, and Instagram onto platforms that are more secretive or specialized, such as Telegram, Gab, and Parler. They act as places for groups that have been banned from the mainstream to create large followings, communities, and broadcast messages in their own, unregulated, news feeds that can be accessed by anyone.49

Extremist Groups

As illustrated by the proud boys becoming part of the national conversation after the president name-dropped them in a debate, and their subsequent capitalization on the resulting media storm, the goal of groups on EMAs is often to manipulate the mainstream media. The idea is to take content from smaller spaces, like EMAs, and get it into the mainstream, as outlined in Claire Wardle’s “Trumpet of Amplification.”50

One of our interviewees, a self-described former member of a “violent white power movement,” argued that the value of Telegram and Discord lies not only in secrecy but also in broadcast and outreach as a step toward mainstream media (the subject also named Riot. IM and Wire as common platforms). On Telegram, users have the option to make messages end-to-end encrypted, but on Discord, messages are only encrypted in transit. Thus, Discord is used to broadcast and bring interested parties into the encrypted fold. EMAs serve a multi-faceted purpose for followers of radical groups who have been kicked off other platforms—it would be a mistake to only define them by their ability to afford the possibility of secret chats.

The interviewee walked us through the details of how spaces like Discord and Telegram are used to spread messages into the mainstream, using the specific example of a fraudulent, opportunistic, and small white supremacist group who managed to convince the mainstream media of the lie that the Parkland shooter was a member of their organization.51 The specifics included a detailed chat log of their real-time media manipulation as they organized on Discord:

Of course, Telegram and Discord are not the only secretive information silos. Facebook, too, enables groups of a closed (one must request membership to see content, but the group is publicly searchable) and secret (groups that cannot be found by those who have not been invited) nature.52 While many groups are used to share legitimate information and encourage comradery, other groups have also been commonly used to spread hate speech and disinformation. Concerningly, Facebook has made it easier for people to be brought into these potential echo chambers with a recent integration of group posts into the newsfeeds of nonmembers.53 Fringe figures have created a presence on Facebook through these groups, where they have been able to create communities and spread disinformation that then finds its way onto mainstream newsfeeds.54

Immigrant Communities in the U.S.

Although WhatsApp’s penetration in the U.S. isn’t as extensive as it is in India or Mexico, it is a popular form of communication in immigrant communities in the U.S.55 Deceptive claims started to spread through the Korean chat app KakaoTalk in Los Angeles and caused widespread fear and panic about infections of the coronavirus.56 Similarly, radicalism and conspiracy theories emerged in Latinx chats in Miami that were originally designed for community engagement and connection.57 For example, an interviewee described to us that they witnessed how WhatsApp groups originally created to connect families displaced by the pandemic with food banks and other services slowly became inundated with politically-motivated conspiracy theories. A Miami community leader and administrator of about 10 of these WhatsApp groups also attested to the increase in mis- and disinformation. They said: “Sometimes, in a period of 5 hours you could have hundreds of postings… When we’re close to an election, I would say 20-30% of them (users) tend to want to convert people or evangelize their political views.” At times, the messages promote harmful conspiracy theories like QAnon.58 After speaking with a member of Miami WhatsApp groups who also works as a political strategist, we were able to understand more deeply how serious these deceptive messages can be: “It hurts me that they would abuse my community this way.” This disinformation sometimes targets existing lines of tension across both the United States and the countries in which immigrant communities have their roots. At times, this targeted messaging is spread using WhatsApp-centric strategies fine-tuned in Latin America by politicians and strategists versed in manipulating messaging on the app: “There are a lot of Latino strategists in Miami that have done Latin American campaigns in Latin America who know how to use this because that’s what they use in Latin America and now they are infiltrating it here.”

EMAs are a vector for this sort of targeted disinformation across international lines. While the infiltration of WhatsApp groups is more difficult than public Facebook groups, our subject articulated that there are strategists and politicians with interests both in the U.S. and internationally that are adapting WhatsApp-centric strategies commonly used in Latin America within the U.S.

India

As internet access increases and the price of data decreases, over 400 million people in India have turned to WhatsApp, making it the app’s largest market.59 The app was widely used in digital political campaigns during the 2019 election, so much so that the election itself was referred to by journalists and academics as a “WhatsApp Election.”60 The disinformation environment on the app has become so apparent that the term “WhatsApp University” has been coined on social media as a satirical jab at WhatsApp as a place for learning, given the prevalence of propaganda and disinformation throughout the app’s chat channels.61

In an effort to quell Covid-19-related mis- and disinformation, WhatsApp implemented several new regulations in early 2020: (1) Limiting the number of users in a group to 256; (2) limiting messaging forwarding to 5 users; (3) offering the ability to search the web for the content of messages straight from the app;62 and, (4) labeling messages with “frequently forwarded flags” after they are shared a specific number of times.63 Nevertheless, the disinformation inside India’s WhatsApp channels has unfortunately resulted in widespread harm and manipulation in the form of rumors, election manipulation, and violence.64 Politically motivated mis- and disinformation spread on WhatsApp is routinely reported to fact-checkers in traditional and mainstream media, such as the Quint’s WebQoof initiative.65 Through our research, we identified several trends in WhatsApp’s role within India’s disinformation environment:

- WhatsApp rumors of child traffickers, thieves, murderers, or other public threats spread throughout channels. Fear and false information have led to the formation of violent mobs who killed dozens of innocent people who were believed to be guilty66

- Capitalizing on WhatsApp’s powerful connectivity and the opportunity for public manipulation, the ruling party runs and maintains what they refer to as “IT cells” across India.67 These IT cells are made up of workers and volunteers who strategically spread false content through WhatsApp channels. Content is designed by workers and leaders of the IT cells to purposely mislead voters and sway public opinion to favor their candidate. These set-ups are hardly a secret in India. In fact, the country’s ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) is widely known to deploy this campaign tactic.68 Such measures were widely used in the 2019 “WhatsApp Elections.”69

- Most of the false political content spread through WhatsApp in India seems to be in favor of Prime Minister Modi and the BJP. Most disinformation seems to have been created to portray his opponents in a negative light or to show Modi as a strong Hindu nationalist.70

- Other political messages aim to ignite religious division throughout the country between Muslims and Hindus. Modi and his party identify with strong Hindu values and have been known to be associated with anti-Muslim biases.71

BJP use of WhatsApp

With a large population in India using WhatsApp, political campaigns began to use WhatsApp as a tool to connect with voters, push their agendas, and spread disinformation. Operations were established to systematically collect data from voters and create and disseminate content to them via WhatsApp. In an interview with a former Indian electoral campaign consultant, we learned about the use of this data in creating messages. “All of these data sets that we compiled and all of these groups that we made of individuals are ultimately used to target people with messaging.” IT Cell workers and volunteers create thousands of WhatsApp groups with users compiled from these data sets and strategically push targeted content to them via WhatsApp chats.72 A senior member of the BJP’s IT operations told us that they work with “volunteers, graphic designers, a few who are good on videos” to create engaging content. They also crowdsource local news stories from followers, which are then reframed to serve the goals of the BJP and distributed on a national scale through the IT Cell WhatsApp groups.

The IT Cell chief has a rosy perspective on his role as a disseminator and democratic equalizer—choosing local news stories reported to him by WhatsApp users to highlight on a national scale that would be otherwise ignored or represented differently: “[The subject’s WhatsApp megaphone] is what the crowdsourcing is all about…that is how the democratic system should work. And, the technology and the social media enables the speed…It’s the people, you can find the people’s content.”

The interviewee stressed the scope and multi-level (from local to nationwide) nature of the WhatsApp groups he maintains and the significant time investment required to maintain them. When questioned about the consequences of WhatsApp’s new forwarding limitations and other regulations,73 they asserted that, due to the networks being maintained through humans and not automated processes like bots, they are not a worry:

Elaborate human-centered efforts, such as the BJP’s IT cells, are at the forefront of harnessing the power of encrypted propaganda, and political actors who have established networks have the advantage of staying one step ahead of regulations.

Mexico

Due to a high level of WhatsApp penetration, challenges with corruption, and a history of early adoption of innovative computational propaganda techniques, Mexico has had a significant share of encrypted propaganda.74 Here is a summary of insights from our top-level results:

- The 2018 presidential elections became a breeding ground for doctored memes, videos, and content meant to influence and intimidate voters across the political spectrum.75

- Amid the COVID-19 pandemic, false information claiming to have come from the government spread as chain messages or through group chats, often accompanied by misleading links, documents, or statements. The intent of the message varied but some pose a threat to public safety and national security.76

- Vulnerable moments, such as the 2017 earthquake, were used as amplifiers for false information to spread quickly about incoming quakes and people in need of aid.77

A prominent Mexican journalist described how WhatsApp interplays with other platforms to buoy and spread disinformation, tracking the case of the 2017 earthquakes described above:

As in India and the United States, EMAs in Mexico are used for mass broadcast and sharing in ways that interplay with other media outlets to increase amplification and eventually make it into mainstream and legacy media. However, much like the human-run networks of the BJP in India and the trend towards human-run networks in the U.S., Mexico is seeing a shift from automated bot networks to more human-centric approaches. A Mexican political consultant and social media manager who specializes in leveraging human accounts on Instagram to generate false support for political clients told us: “WhatsApp works with different strategies [than Facebook and Instagram], like the planting of false information. You build a solid base of WhatsApp numbers and create a bot to plant the information in whatever geographic location you want. … This has always happened, but it went from SMS to WhatsApp because it’s cheaper.”

The interviewee is one of many political actors in Mexico who consider their work to be, essentially, a form of social media marketing and an extension of the give and take between users and social media platforms. The same person further described their job as follows: “My main job focus is growth hacking, where I find new roads or new ways to reach a certain goal within social media by using different strategies and tools, a little bit of black sale and of maneuvering the terms and conditions of these different platforms … to accelerate their algorithms and growth in general.” This person presented themselves as a social media marketer and goes as far as featuring the term “astroturfing” on their public LinkedIn profile. This is a demonstration of the diverse, cross-platform nature and shifting strategies of actors seeking to stay ahead of platform regulations—the anonymity and scale provided by an encrypted space like WhatsApp is only one strategy in a larger set of services provided.

CONCLUSION

A Diverse Propaganda Tool Mistakenly Defined by One Feature

As encrypted messaging applications (EMAs) such as WhatsApp and Telegram enjoy a large popularity among users worldwide, they are also venues prone to the dissemination of disinformation—a phenomenon we call encrypted propaganda. In this study, we showcased national and international trends in encrypted propaganda, with a particular emphasis on white nationalists in the United States, the political use of these apps in India, perhaps best illustrated by the Bharatiya Janata Party, as well as false information spreading on WhatsApp in Mexico, elevated by campaigners under the guise of social media marketing. While conversations about encrypted spaces often focus on the dangers that emanate from the lack of access for authorities, especially in the tracing of rumors that lead to acts of physical violence, EMAs are also powerful tools for strategists that utilize their human-powered networks to get their message across. Additionally, and counterintuitively, EMAs are appealing to groups seeking to publicly broadcast information, but who have been removed from mainstream social media platforms. Public channels on EMAs facilitate the recruitment of new members, who are then invited into encrypted channels within the same platform. Recognizing that the uses of EMAs are as variable as those who are using them is a first step towards designing and implementing meaningful strategies to curb the freely-flowing disinformation that has come to define them in recent years.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Thank you to Joel Carter for his editorial help and Claire Coburn for her research assistance. This report was funded by Omidyar Network, Open Society Foundations, and the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation.

SUGGESTED CITATION:

Gursky, J., Glover, K., Joseff, K., Riedl, M.J., Pinzon, J., Geller, R., & Woolley, S. C. (2020, October 26). Encrypted propaganda: Political manipulation via encrypted messages apps in the United States, India, and Mexico. Center for Media Engagement. https://mediaengagement.org/research/encrypted-propaganda

- We define EMAs as digital communication platforms using both end-to-end and transport-layer encryption. [↩]

- Bucher, B. (2020, July 30). Messaging App Usage Statistics Around the World. MessengerPeople. https://www. com/global-messenger-usage-statistics/ [↩]

- Love, N. S. (2017). Back to the future: trendy fascism, the Trump effect, and the alt-right. New Political Science, 39(2), 263-268. https://doi.org/10.1080/07393148.2017.1301321 [↩]

- Proud boys. Anti-Defamation League. https://www.adl.org/proudboys ; Proud boys. Southern Poverty Law Center. https:// splcenter.org/fighting-hate/extremist-files/group/proud-boys. [↩]

- “There Is No Political Solution”: Accelerationism in the White Power Movement. (n.d.). Southern Poverty Law Center. https:// splcenter.org/hatewatch/2020/06/23/there-no-political-solution-accelerationism-white-power-movement. [↩]

- Frenkel, S., & Karni, A. (2020, September 30). Proud boys celebrate Trump’s ‘stand by’ remark about them at the debate. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/09/29/us/trump-proud-boys-biden.html.[↩]

- Rogers, R. (2020). Deplatforming: Following extreme Internet celebrities to Telegram and alternative social media. European Journal of Communication, 35(3), 213–229. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267323120922066 [↩]

- Urman, A., & Katz, S. (2020). What they do in the shadows: examining the far-right networks on Telegram. Information, Communication & Society. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2020.1803946 [↩]

- Bloom, M., & Daymon, C. (2018). Assessing the Future Threat: ISIS’s Virtual Caliphate. Orbis, 62(3), 372-388. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.orbis.2018.05.007 [↩]

- Baumgartner, J., Zannettou, S., Squire, M., & Blackburn, J. (2020, May). The Pushshift Telegram Dataset. In Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media (Vol. 14, pp. 840-847). [↩]

- Woolley, Samuel C., et al. “Incubating Hate: Islamophobia and Gab.” The German Marshall Fund of the United States, 21 June 2019, www.gmfus.org/publications/incubating-hate-islamophobia-and-gab. [↩]

- Benkler, Y., Faris, R., & Roberts, H. (2018). Network propaganda: Manipulation, disinformation, and radicalization in American politics. Oxford University Press. [↩]

- Case list available upon request at mediaengagement@austin.utexas.edu. [↩]

- Oxford English Dictionary. (n.d.). Disinformation. In OED. https://www.oed.com/; Wardle, C. (2017, February 16). Fake news. It’s complicated. First Draft. https://firstdraftnews.org/latest/fake-news-complicated/. [↩]

- Larson, E. V., Darilek, R. E., Gibran, D., Nichiporuk, B., Richardson, A., Schwartz, L. H., & Thurston, C. Q. (2009). Foundations of effective influence operations: A framework for enhancing army capabilities. RAND Arroyo Center. https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/ citations/ADA503375.[↩]

- Knuckey, J., & Hassan, K. (2020). Authoritarianism and support for Trump in the 2016 presidential election. The Social Science Journal. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soscij.2019.06.008 ; Chacko, P. (2018). The right turn in India: Authoritarianism, populism, and neoliberalisation. Journal of Contemporary Asia, 48(4), 541-565. [↩]

- Grillo, I. (2020, September 29). Mexico and the Gods of Corruption. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes. com/2020/09/29/opinion/international-world/mexico-corruption-lopez-obrador.html. [↩]

- Newman, N. (2020, May 23). United States. Digital News Report: Reuters Institute and University of Oxford. http://www. org/survey/2020/united-states-2020/. [↩]

- Newman, N. (2020, May 23). Mexico. Digital News Report: Reuters Institute and University of Oxford. http://www.digitalnewsreport.org/survey/2020/mexico-2020/. [↩]

- Bhushan , K. (2019, July 26). WhatsApp now has about 400 million users in India. Hindustan Times Tech. https://tech. hindustantimes.com/tech/news/whatsapp-now-has-about-400-million-users-in-india-story-CT4v7JjYjmcb8YKIQiSkXJ.html. [↩]

- The World Factbook: India. (2018, February 1). https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/in.html. [↩]

- Balkrishan, D., Joshi, A., Rajendran, C., Nizam, N., Parab, C., & Devkar, S. (2016, December). Making and breaking the user-usage model: Whatsapp adoption amongst emergent users in India. In Proceedings of the 8th Indian Conference on Human Computer Interaction (pp. 52-63). [↩]

- Clement, J. (2019, September 18). Topic: WhatsApp. Statista. https://www.statista.com/topics/2018/whatsapp/. [↩]

- Singh, M. (2020, April 24). Telegram hits 400M monthly active users. TechCrunch. https://www.yahoo.com/now/telegram-hits400-million-monthly-112614713.html?guccounter=1. [↩]

- Abu-Salma, R., Sasse, M. A., Bonneau, J., Danilova, A., Naiakshina, A., & Smith, M. (2017, May). Obstacles to the adoption of secure communication tools. In 2017 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP) (pp. 137-153). IEEE. [↩]

- Other than public group content on some EMAs and metadata on who is sending and receiving messages on e2e platforms. Transport layer encrypted apps, meanwhile, allow those who own the apps proprietary access to communication stored on their servers. [↩]

- Benkler, Y., Faris, R., & Roberts, H. (2018). Network propaganda: Manipulation, disinformation, and radicalization in American politics. Oxford University Press ; Woolley, S. C., & Howard, P. N. (Eds.). (2018). Computational propaganda: political parties, politicians, and political manipulation on social media. Oxford University Press. [↩]

- Reis, J., Melo, P. D. F., Garimella, K., & Benevenuto, F. (2020). Detecting Misinformation on WhatsApp without Breaking Encryption. arXiv preprint arXiv:2006.02471. [↩]

- Thinking of Giving Up’: How Narendra Modi Has Used Social Media to Fuel His Politics. The Wire. (2020, March 3). https:// thewire.in/politics/narendra-modi-social-media-account ; Breland, A. (2019, July 10). Trump is having a social media summit and the White House invited lots of right-wing trolls. Mother Jones. https://www.motherjones.com/politics/2019/07/whitehouse-social-media-summit-guest-list-1/. [↩]

- Goel, V., Raj, S., & Ravichandran, P. (2018, July 18). How WhatsApp Leads Mobs to Murder in India. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2018/07/18/technology/whatsapp-india-killings.html ; Roose, K. (2018, October 28). On Gab, an Extremist-Friendly Site, Pittsburgh Shooting Suspect Aired His Hatred in Full. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes. com/2018/10/28/us/gab-robert-bowers-pittsburgh-synagogue-shootings.html ; Martinez, M. (2018, November 12). Burned to death because of a rumour on WhatsApp. BBC. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-46145986. [↩]

- BBC. (2018, July 18). How WhatsApp helped turn an Indian village into a lynch mob. https://www.bbc.com/news/worldasia-india-44856910 ; Terzeon , J. (2018, November 13). This town descended into a murderous mob because of a rumour on WhatsApp. VT. https://vt.co/sci-tech/this-town-descended-into-a-murderous-mob-because-of-a-rumour-on-whatsapp/. [↩]

- Breland, A. (2019, July 10). Trump is having a social media summit and the White House invited lots of right-wing trolls. Mother Jones. https://www.motherjones.com/politics/2019/07/white-house-social-media-summit-guest-list-1/. [↩]

- Chaturvedi, S. (2016). I am a troll: Inside the secret world of the BJP’s digital army. Juggernaut Books. [↩]

- Chunduru, A. (2019, December 31). BJP’s pro-CAA surge ‘scripted’. Deccan Chronicle. https://www.deccanchronicle.com/ nation/politics/311219/bjps-pro-caa-surge-scripted.html. [↩]

- ‘Plevin, R. (2019, February 28). ‘We’re going to find you.’ Mexican cartels turn social media into tools for extortion, threats and violence. Desert Sun. https://www.desertsun.com/in-depth/news/2019/02/27/mexican-drug-cartels-use-social-media-forextortion-threats-violence-facebook-whatsapp-youtube/2280756002/. [↩]

- Manjoo, F. (2016, December 21). For millions of immigrants, a common language: WhatsApp. The New York Times. https:// nytimes.com/2016/12/21/technology/for-millions-of-immigrants-a-common-language-whatsapp.html. [↩]

- Markus, D., & Frank, A. (2020, March 5). How the coronavirus rumor mill can thrive in private group chats. Vox. https://www. com/2020/3/5/21165238/coronavirus-rumors-myths-facebook-whatsapp-podcast ; Rodriguez, S., & Caputo, M. (2020, September 14). ‘This is f—ing crazy’: Florida Latinos swamped by wild conspiracy theories. Politico. https://www.politico.com/ news/2020/09/14/florida-latinos-disinformation-413923. [↩]

- Krafft, P. M., & Donovan, J. (2020). Disinformation by Design: The Use of Evidence Collages and Platform Filtering in a Media Manipulation Campaign. Political Communication, 37(2), 194-214. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2019.1686094 [↩]

- Roose, K. (2018, October 28). On Gab, an Extremist-Friendly Site, Pittsburgh Shooting Suspect Aired His Hatred in Full. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/10/28/us/gab-robert-bowers-pittsburgh-synagogue-shootings.html. [↩]

- Makuch, B. (2019, July 11). Mastodon Was Designed to Be a Nazi-Free TwitterNow It’s the Exact Opposite. Vice. https://www. vice.com/en/article/mb8y3x/the-nazi-free-alternative-to-twitter-is-now-home-to-the-biggest-far-right-social-network. [↩]

- Timberg, C. (2020, October 7). Parler and Gab, two conservative social media sites, keep alleged Russian disinformation up, despite report. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2020/10/07/russian-trolls-graphika-parlergab/.[↩]

- Glaser, A. (2018, October 9). White Supremacists Still Have a Safe Space Online. It’s Discord. Slate Magazine. https://slate.com/ technology/2018/10/discord-safe-space-white-supremacists.html. [↩]

- Guhl, J., & Davey, J. (2020). A Safe Space to Hate: White Supremacist Mobilisation on Telegram. https://www.isdglobal.org/ wp-content/uploads/2020/06/A-Safe-Space-to-Hate.pdf. [↩]

- Makuch, B. (2019, July 11). Mastodon Was Designed to Be a Nazi-Free Twitter-Now It’s the Exact Opposite. Vice. https:// vice.com/en/article/mb8y3x/the-nazi-free-alternative-to-twitter-is-now-home-to-the-biggest-far-right-social-network ; Robertson, A. (2019, July 12). How the biggest decentralized social network is dealing with its Nazi problem. The Verge. https:// www.theverge.com/2019/7/12/20691957/mastodon-decentralized-social-network-gab-migration-fediverse-app-blocking ; Roose, K. (2018, November 4). We Asked for Examples of Election Misinformation. You Delivered. The New York Times. https:// www.nytimes.com/2018/11/04/us/politics/election-misinformation-facebook.html. [↩]

- Barlow, R. (2019, April 23). White Supremacy Is Metastasizing – In Video Games. Cognoscenti. https://www.wbur.org/ cognoscenti/2019/04/23/video-games-white-supremacy-rich-barlow ; Condis, M. (2019, March 27). From Fortnite to Alt-Right. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/03/27/opinion/gaming-new-zealand-shooter.html. [↩]

- Silverman, C. (2020, March 12). That Viral Post With Coronavirus Tips Has Some Really Bad Advice. BuzzFeed News. https:// buzzfeednews.com/article/craigsilverman/coronavirus-drink-water-advice-debunk?origin=thum ; Wilson, J. (2020, March 19). Disinformation and scapegoating: how America’s far right is responding to coronavirus. The Guardian. https:// www.theguardian.com/world/2020/mar/19/america-far-right-coronavirus-outbreak-trump-alex-jones ; Malik, N. (2020, March 26). Self-Isolation Might Stop Coronavirus, but It Will Speed the Spread of Extremism. Foreign Policy. https://foreignpolicy. com/2020/03/26/self-isolation-might-stop-coronavirus-but-spread-extremism/ ; Porter, T. (2020, April 23). Advocates of a toxic bleach fake “miracle cure” are telling desperate people it can cure the coronavirus in thriving groups on Telegram. Business Insider. https://www.businessinsider.com/mms-bleach-advocates-telegram-photos-child-injuries-2020-4. [↩]

- Rodriguez, S., & Caputo, M. (2020, September 14). ‘This is f—ing crazy’: Florida Latinos swamped by wild conspiracy theories. Politico. https://www.politico.com/news/2020/09/14/florida-latinos-disinformation-413923. [↩]

- Frank, A., & Markus, D. (2020, March 5). How the coronavirus rumor mill can thrive in private group chats. Vox. https://www. com/2020/3/5/21165238/coronavirus-rumors-myths-facebook-whatsapp-podcast. [↩]

- Bloom, M., Tiflati, H., & Horgan, J. (2019). Navigating ISIS’s preferred platform: Telegram. Terrorism and Political Violence, 31(6), 1242-1254. https://doi.org/10.1080/09546553.2017.1339695 [↩]

- Wardle, C. (2018, December 27). 5 Lessons for Reporting in an Age of Disinformation. First Draft News. https://firstdraftnews. org/latest/5-lessons-for-reporting-in-an-age-of-disinformation/. [↩]

- Beaty, T., & Decker, B. T. (2018, March 6). Source Hacking: A Disinformation Retrospective on the Parkland Shooting. https:// com/1st-draft/source-hacking-a-disinformation-retrospective-on-the-parkland-shooting-585990dbb669. [↩]

- Gebhart, G. (2020, July 10). Understanding Public, Closed, and Secret Facebook Groups. Electronic Frontier Foundation. https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2017/06/understanding-public-closed-and-secret-facebook-groups. [↩]

- Holt, K. (2020, October 1). Facebook will start surfacing public group posts in News Feeds. Engadget. https://www.engadget.com/facebook-groups-updates-features-public-posts-news-feeds-174954540.html?guccounter=1. [↩]

- Roose, K. (2018, September 3). Facebook’s Private Groups Offer Refuge to Fringe Figures. The New York Times. https://www. com/2018/09/03/technology/facebook-private-groups-alex-jones.html. [↩]

- Manjoo, F. (2016, December 21). For millions of immigrants, a common language: WhatsApp. The New York Times. https:// nytimes.com/2016/12/21/technology/for-millions-of-immigrants-a-common-language-whatsapp.html. [↩]

- Allegra Frank, D. M. (2020, March 5). How the coronavirus rumor mill can thrive in private group chats. Vox. https://www.vox.com/2020/3/5/21165238/coronavirus-rumors-myths-facebook-whatsapp-podcast. [↩]

- Rodriguez, S., & Caputo, M. (2020, September 14). ‘This is f—ing crazy’: Florida Latinos swamped by wild conspiracy theories. Politico. https://www.politico.com/news/2020/09/14/florida-latinos-disinformation-413923. [↩]

- Roose, K. (2020, August 18). What Is QAnon, the Viral Pro-Trump Conspiracy Theory? The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/article/what-is-qanon.html. [↩]

- Singh, M. (2019, July 26). WhatsApp reaches 400 million users in India, its biggest market. TechCrunch. https://techcrunch. com/2019/07/26/whatsapp-india-users-400-million/ ; The Economic Times. (2019, March 6). Mobile data price in India: India has the cheapest mobile data in world: Study. https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/tech/internet/india-has-the-cheapestmobile-data-in-world-study/articleshow/68285820.cms. [↩]

- Bengani, P. (2019, October 16). India had its first ‘WhatsApp election.’ We have a million messages from it. https://www.cjr. org/tow_center/india-whatsapp-analysis-election-security.php ; Poonam, S., & Bansal, S. (2019, April 1). Misinformation Is Endangering India’s Election. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2019/04/india-misinformationelection-fake-news/586123/. [↩]

- Iyer, S. (2019, November 23). The Great Indian WhatsApp University. The Cyber Blog India. https://cyberblogindia.in/thegreat-indian-whatsapp-university/. [↩]

- Still, J. (2020, October 2). How to use WhatsApp’s fact-checking feature to research the validity of viral, forwarded messages. Business Insider. https://www.businessinsider.com/how-to-use-whatsapp-fact-check. [↩]

- WhatsApp FAQ – Tips to help prevent the spread of rumors and fake news. https://faq.whatsapp.com/general/security-andprivacy/tips-to-help-prevent-the-spread-of-rumors-and-fake-news/?lang=en. [↩]

- Arun, C. (2019). On whatsapp, rumours, and lynchings. Economic & Political Weekly, 54(6), 30-35.; Narayanan, V., Kollanyi, B., Hajela, R., Barthwal, A., Marchal, N., & Howard, P. N. (2019). News and information over Facebook and WhatsApp during the Indian election campaign. Data Memo. [↩]

- Fact Check of Viral Fake News, Photos & Video on Social Media, Analysis of False Information Available Online – The Quint WebQoof. TheQuint. https://www.thequint.com/news/webqoof. [↩]

- Gani, A. (2018, June 11). India arrests 18 after two men lynched over WhatsApp rumours. Al Jazeera. https://www. com/news/2018/06/11/india-arrests-18-after-two-men-lynched-over-whatsapp-rumours/ ; N, S. (2018, May 10). Tiruvannamalai temple visit turns tragic as village mob beats 65-year-old woman to death, injures 4 others. The New Indian Express. https://www.newindianexpress.com/states/tamil-nadu/2018/may/10/tiruvannamalai-temple-visit-turns-tragic-asvillage-mob-beats-65-year-old-woman-to-death-injures-4-1812660.html ; Phartiyal, S., Patnaik, S., & Ingram, D. (2018, June 25). When a text can trigger a lynching: WhatsApp struggles with incendiary messages in India. Reuters. https://www.reuters. com/article/us-facebook-india-whatsapp-fake-news/when-a-text-can-trigger-a-lynching-whatsapp-struggles-with-incendiarymessages-in-india-idUSKBN1JL0OW ; Press Trust of India. (2018, July 4). Fuelled by WhatsApp rumours, Dhule mob wanted to burn bodies of ‘child abductors’. Hindustan Times. https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/furious-dhule-mob-wantedto-burn-bodies-of-child-abductors-after-beating-them-to-death/story-pqH4MFa8YRc9ofxJLPgWOK.html ; Saha, A. (2018, July 1). Three lynched in a day over ‘child-lifting’, Tripura minister stands by role in one rumour. The New Indian Express. https:// indianexpress.com/article/north-east-india/tripura/tripura-lynching-police-fake-news-social-media-north-east-5240292/. [↩]

- Arnimesh, S. (2020, July 1). 9,500 IT cell heads, 72,000 WhatsApp groups — how BJP is preparing for Bihar poll battle. ThePrint. https://theprint.in/politics/9500-it-cell-heads-72000-whatsapp-groups-how-bjp-is-preparing-for-bihar-pollbattle/451740/. Chaturvedi, S. (2016). I am a troll: Inside the secret world of the BJP’s digital army. Juggernaut Books. [↩]

- Chaturvedi, S. (2016). I am a troll: Inside the secret world of the BJP’s digital army. Juggernaut Books. [↩]

- Ayed, N., & Jenzer, S. (2019, May 17). ‘The battle is still on’: Fake news rages in India’s WhatsApp elections. CBC News. https:// cbc.ca/news/world/india-whatsapp-fake-news-1.5139726 ; Bengani, P. (2019, October 16). India had its first ‘WhatsApp election.’ We have a million messages from it. https://www.cjr.org/tow_center/india-whatsapp-analysis-election-security.php ; Poonam, S., & Bansal, S. (2019, April 5). Misinformation Is Endangering India’s Election. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic. com/international/archive/2019/04/india-misinformation-election-fake-news/586123/ ; Sharma, B. (2019, May 13). Election 2019: A BJP Voter’s WhatsApp Is The Stuff Of Nightmares. HuffPost. https://www.huffingtonpost.in/entry/election-2019-a-bjpvoters-whatsapp-is-the-stuff-of-nightmares_in_5cb06b64e4b098b9a2d22bf0. [↩]

- Patel, J. (2019, January 9). Death of priest at Raebareli temple communalised on social media. https://www.altnews.in/ death-of-priest-at-raebareli-temple-communalised-on-social-media/ ; Perrigo, B. (2019, January 25). How Whatsapp Is Fueling Fake News Ahead of India’s Elections. https://time.com/5512032/whatsapp-india-election-2019/ ; First Post Staff. (2019, April 8). Fact Check: Fake BBC survey claiming BJP’s landslide victory going viral on social media, media firm confirms inauthenticity – India News , Firstpost. https://www.firstpost.com/india/fact-checker-fake-bbc-survey-claiming-bjps-landslide-victory-goingviral-on-social-media-media-firm-confirms-inauthenticity-6423231.html ; Kudrati, M. (2019, May 16). This Picture Of Donald Trump Endorsing PM Modi Is A Hoax. https://www.boomlive.in/this-picture-of-donald-trump-endorsing-pm-modi-is-ahoax/?infinitescroll=1 ; Sidharth, A. (2019, December 26). Meme shared as pro-Modi cartoon on CAA and NRC published by European newspaper. https://www.altnews.in/meme-shared-as-pro-modi-cartoon-on-caa-and-nrc-published-by-europeannewspaper/. [↩]

- Patel, J. (2019, January 9). Death of priest at Raebareli temple communalised on social media. https://www.altnews.in/deathof-priest-at-raebareli-temple-communalised-on-social-media/ ; Perrigo, B. (2019, January 25). How Whatsapp Is Fueling Fake News Ahead of India’s Elections. TIME. https://time.com/5512032/whatsapp-india-election-2019/ ; Sharma, B. (2019, May 13). Election 2019: A BJP Voter’s WhatsApp Is The Stuff Of Nightmares. HuffPost. https://www.huffingtonpost.in/entry/election2019-a-bjp-voters-whatsapp-is-the-stuff-of-nightmares_in_5cb06b64e4b098b9a2d22bf0. [↩]

- Arnimesh, S. (2020, July 1). 9,500 IT cell heads, 72,000 WhatsApp groups — how BJP is preparing for Bihar poll battle. ThePrint. https://theprint.in/politics/9500-it-cell-heads-72000-whatsapp-groups-how-bjp-is-preparing-for-bihar-pollbattle/451740/. [↩]

- Still, J. (2020, October 2). How to use WhatsApp’s fact-checking feature to research the validity of viral, forwarded messages. Business Insider. https://www.businessinsider.com/how-to-use-whatsapp-fact-check ; WhatsApp FAQ – Tips to help prevent the spread of rumors and fake news. WhatsApp. https://faq.whatsapp.com/general/security-and-privacy/tips-to-help-prevent-thespread-of-rumors-and-fake-news/?lang=en. [↩]

- Armstrong, M. (2018, August 2). Here’s What We Can Learn From Disinformation in Mexico’s Recent Presidential Election. Slate Magazine. https://slate.com/technology/2018/08/mexicos-presidential-election-was-rife-with-disinformation-frominside-the-country.html ; O’Carroll, T. (2017, January 24). Mexico’s misinformation wars: How organized troll networks attack and harass journalists and activists in Mexico. Amnesty International. https://medium.com/amnesty-insights/mexico-smisinformation-wars-cb748ecb32e9. [↩]

- Patel, J. (2019, January 9). Death of priest at Raebareli temple communalised on social media. Alt News. https://www. altnews.in/death-of-priest-at-raebareli-temple-communalised-on-social-media/ ; Funke, D. (2018, July 9). WhatsApp on its misinformation problem: Fact-checking is going to be essential. Poynter Institute. https://www.poynter.org/fact-checking/2018/ whatsapp-on-its-misinformation-problem-%C2%91fact-checking-is-going-to-be-essential%C2%92/ ; Love, J., Menn, J., & Ingram, D. (2018, June 28). In Mexico, fake news creators up their game ahead of election. Reuters. https://in.reuters.com/article/ mexico-facebook/in-mexico-fake-news-creators-up-their-game-ahead-of-election-idINKBN1JO2Y1 ; Owen , L. (2018, June 1). WhatsApp is a black box for fake news. Verificado 2018 is making real progress fixing that. NiemanLab. https://www.niemanlab.org/2018/06/whatsapp-is-a-black-box-for-fake-news-verificado-2018-is-making-real-progress-fixing-that/. [↩]

- Medios, C. M. S. (2020, March 24). Detectan entrega falsa de bonos en WhatsApp por cuarentena. El Imparcial. https://www. com/mexicali/mexicali/Detectan-entrega-falsa-de-bonos-en-WhatsApp-por-cuarentena-20200323-0024.html ; Terzeon , J. (2018, November 13). This town descended into a murderous mob because of a rumour on WhatsApp. VT. https:// vt.co/sci-tech/this-town-descended-into-a-murderous-mob-because-of-a-rumour-on-whatsapp/ ; Megamedia. (2020, March 19). Cadena de Whatsapp del estado de emergencia en México es falsa. Diario de Yucatán. https://www.yucatan.com.mx/ mexico/cadena-de-whatsapp-del-estado-de-emergencia-en-mexico-es-falsa ; Sang, L. S. (2018, November 14). Mob burned to death two men falsely accused of child organ trafficking, report says. Fox News. https://www.foxnews.com/world/mob-beat-litof-fire-2-mexican-men-falsely-accused-of-child-organ-trafficking-on-whatsapp-report. [↩]

- Shareable. (2020, May 12). Fighting misinformation after the Mexico City earthquake. https://www.shareable.net/responsepodcast-fighting-misinformation-in-the-aftermath-of-the-mexico-city-earthquake/ ; Noel, A. (2017, September 20). The Great Mexico Quake: A Tale of Heroes and Trolls. The Daily Beast. https://www.thedailybeast.com/the-great-mexico-quake-a-tale-ofheroes-and-trolls. [↩]