Most Americans think that special interests have too much power in Washington (De Witte, 2018). Many people see Washington as full of lobbyists and insiders trading money for access and favors – lobbying has even been called legalized bribery. Less appreciated is the information and support service, or legislative subsidy, that lobbyists provide policymakers. This subsidy can be invaluable to a legislator and her constituents – but comes with its own set of complicated ethical questions.

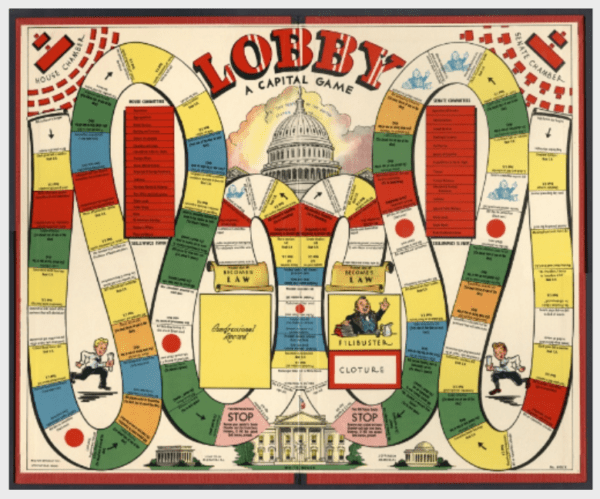

Advocates were cornering elected officials in lobbies of buildings for more than 100 years before the first US Congress met in 1789 (Hansen, 2006). Barely three years later “Virginia Revolutionary War veterans hired William Hull to lobby congress for more pay” (Keefe, 2017). The advocacy for hire industry has been humming along – for better and for worse – ever since. In 1949, the toy company Milton Bradley even sold a game called “Lobby: A Capital Game” (Art, 2019).

Complaints of corruption are just as old. In the 1850s the gun manufacturer Colt handed out pistols to try to persuade Congress to extend one of its patents, and in 1875 a lobbyist named Sam Ward got in trouble for allegedly doling out $100,000 in bribes (Grier, 2009). A political cartoon in 1889 featured overweight men with muttonchops and moneyed interests written on their chest standing behind United States Senators, and in 1937 Representative Alfred N. Phillips (D-CT) had a sign on his office door reading: “Come in! Everyone welcome except professional lobbyists” (National Museum of American History, n.d.). In 2020, Joe Biden’s presidential campaign was criticized for having lobbyists as part of his transition team organized in advance of a possible electoral victory (Nichols, 2020). And so it goes.

Public outcry about lobbying has led to attempts to reign it in, make the process more transparent, and otherwise ensure the public good is put ahead of private interest. Those attempts have not always worked. One critic of a 2007 reform bill wrote, “Not only did the lobbying reform bill fail to slow the revolving door, it created an entire class of professional influencers who operate in the shadows, out of the public eye and unaccountable” (Arnsdorf, 2016). Even when it’s legal, lobbying can still smell bad.

Most lobbyists and elected officials are honest, hardworking people doing the best job they can. Sometimes elected officials, like everyone else, let greed overwhelm good judgment. As Republican and Democratic lobbyists Matthew L. Johnson and Israel S. Kline write, “Like a baseball umpire who makes a bad call, the public only knows a lobbyist’s name when the person messes up” (Johnson & Kline, 2020).

Those who support lobbying point out that it is protected under the First Amendment of the US Constitution – lobbying is exercising the right to petition our government – and that it is also necessary. Lobbyists have long provided expertise and insight to policymakers. As Johnson and Kline note, in 1956 then Senator John F. Kennedy wrote that lobbyists “serve a useful purpose” because they are “often expert technicians and capable of explaining complex and difficult subjects in a clear, understandable fashion” (Johnson & Kline, 2020).

This need for outside expertise has grown more acute in recent years. A 2020 study from the New America Foundation found that Congress increasingly relies on lobbyists for substantive expertise (Furnas & LaPira, 2020). The number of constituents most Members of Congress represent is growing, while the budget every Representative gets to spend on staff is shrinking. More of the budget that is left goes to staff in the Congressional district, and less goes to policy staff. At the same time, budgets for Congressional support services such as the Congressional Research Service are also shrinking. Those in charge of establishing national policy on everything from taxes and trade, to national defense and climate change, and much more, have greater demands and fewer resources available to deal with them than in the past. The Congressional staff who remain are by and large young, inexperienced, and typically only work on Capitol Hill for three years before decamping to the private sector or advocacy organizations.

Two of the most important commodities any of us have are our time and our attention. While you are reading this you are not doing something else. While you are thinking about ethics in political communication, you are not thinking about the economy, civil rights, the environment, or your best friend’s birthday. Just like the rest of us, elected officials and their staff have neither the time nor the resources to do all they would like to do. And just like the rest of us who rely on review sites to help us choose where to eat and what computer to buy, Congress and their staff turn to outside experts with time and expertise needed to help make important decisions. Those decisions, of course, impact more than whether or not someone gets a good burger. Those decisions effect your life and mine.

That’s where lobbyist come in. Lobbyists provide outside expertise, write talking points, suggest legislative language, build and manage advocacy coalitions, and otherwise do the work of turning ideas into policy. Lobbyists do not ask elected officials for favors, they do favors for elected officials. They find an issue about which a legislator cares, attach their organization’s or client’s priority to that issue, and work to advance both at the same time. In this way, the lobbyist is helping a legislator achieve her goals by advancing the organization’s or client’s goals (Hall & Deardorff, 2006). They do the work of Congressional staff, but that work is paid for by whoever is paying the lobbyist rather than by the Congressional office. Lobbyists, in effect, subsidize the work of Congress.

For example, if a Representative wants to help small manufacturing firms in her district, a lobbyist might identify tax breaks that could help. The lobbyist would suggest how the break helps the Representative’s constituents, generate support for the idea both in Washington and in the Congressional district, reach out to the media supporting the idea, and so on. The lobbyist is helping an elected official do her job, and ensures she gets the credit she deserves from voters.

More often than not, those proposing the idea, talking to the Representative and her staff, writing the talking points, and so on are former Congressional staff. These former staff have policy expertise, know what the legislator cares about, and how the political and policy process works. They are doing the same things as lobbyists they did as staff – they are trusted advisors helping advance the legislator’s agenda. The difference is who pays them, and why.

A lobbyist doesn’t help a Congressional office out of the kindness of her heart. When, how, and on what issues they provide help is strategic (Ellis & Groll, 2020). The lobbyist is being paid by someone who will benefit from the new rules. The client or organization may be a good one, and the proposal might be sound, but the motivation is private interest rather than public good.

In the example above, while the Representative and her staff are working with the lobbyist on manufacturing jobs, they are not talking to teachers about conditions in schools. They are not using their limited time and attention to talk to scientists about climate, to doctors about vaccinations, to college students about debt, or other issues that may matter more to their constituents than a tax break for some kinds of companies (Hertel-Fernandez, Mildenberger, & Stokes, 2018). Lobbyists help decide which issues get discussed, and in what terms they are discussed. This also means they help decide which issues get ignored, and what angles of an issue are not considered.

The same holds for Congressional oversight of agencies. Lobbyists “raise the alarm” about issues that need attention, help legislators do the work of oversight of federal agencies, and provide solutions to the problems they have found (Hall & Miller, 2008) Lobbyists serve the role of staff or engaged citizens by drawing attention to problems and identifying possible solutions. Unlike citizens or staff, the lobbyists have a financial interest in the problems they find and solutions they propose –the problems are real, and the solutions may be good ones, but the action is driven by private interest.

The relationship between private interest and legislative action is more complex than simply trading money for favors or access (if it were just about money there would be no need for lobbyists with policy, process, and press expertise). The ethical question is not about buying laws, it is about giving time. Congress works on the problems in front of it and considers the problems – and solutions – from the angles it sees. Congress relies on outside expertise to help identify those problems and solutions to those problems. Policymakers rely on expertise they cannot maintain internally, and on help making the case for policies and to build support for new ideas. Selecting the experts, problems, solutions, and support requires considering policy, politics, and ethics.

Discussion Questions:

- Is lobbying a good practice for a democratic system of government representing the populace? What’s worrisome or beneficial about lobbying?

- One way to decrease the power of lobbyists is to increase the size of the House of Representatives and to significantly increase congressional office budgets to both spread the work around and make the job of being a congressional staffer more attractive. Should congress vote to effectively increase its own pay and power?

- If lobbying is both constitutionally protected and provides a useful service, how can advocates ensure the activity is as ethical as possible?

- Should policymakers ignore lobbyists and focus instead on issues more important to their constituents, even if the tradeoff means finding less effective solutions or possibly missing other important problems?

Further Information:

Arnsdorf, Isaac (July 3, 2016). “The Lobbying Reform that Enriched Congress.” Politico. Available at: https://www.politico.com/story/2016/06/the-lobbying-reform-that-enriched-congress-22484

Art (Jan. 21, 2015). “Lobbying in the Lobby.” Whereas: Stories from the People’s House, History, Art and Archives US House of Representatives. Available at: https://history.house.gov/Blog/2015/January/01-21-Lobby/#:~:text=The%20switch%20to%20a%20political,of%20the%20term%20in%20print

Art (Jan. 21, 2015). “Lobby: A Capital Game.” Whereas: Stories from the People’s House, History, Art and Archives US House of Representatives. Available at: https://history.house.gov/Blog/2019/October/10-2-lobby/

De Witte, Melissa (Feb. 26, 2018). “Americans’ low opinion of elected officials tied to perceptions of decision-making, Stanford researchers find.” Stanford News Service Available at: https://news.stanford.edu/press-releases/2018/02/26/americans-dont-tlected-officials/

Ellis, Christopher J. and Thomas Groll (2020). “Strategic Legislative Subsidies: Informational Lobbying and the Cost of Policy.” American Political Science Review Vol 114 No 1, pp 179-205.

Furnas, Alexander and Timothy M. LaPira (Sept. 8, 2020). “Congressional Brain Drain.” Available at https://www.newamerica.org/political-reform/reports/congressional-brain-drain/

Grier, Peter (Sept. 28, 2009) “The Lobbyist Through History – Villainy and Virtue.” Christian Science Monitor Available at: https://www.csmonitor.com/USA/Politics/2009/0928/the-lobbyist-through-history-villainy-and-virtue

Hall, Richard L. and Alan V. Deardorff (2006). “Lobbying as Legislative Subsidy.” American Political Science Review Vol 100 No 1, pp 69 – 84.

Hall, Richard L. and Kristina C. Miller (Oct. 2008). “What Happens After the Alarm? Interest Group Subsidies to Legislative Overseers.” Journal of Politics Vol. 70 No. 4 pp. 990- 1005.

Hansen, Liane (Jan. 22, 2006). “A Lobbyist by Any Other Name?” Weekend Edition Sunday, National Public Radio. Available at https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=5167187

Hertel-Fernandez, Alexander, Matto Mildenberger and Leah C. Stokes (Oct. 31, 2018). “Congress Has No Clue What Americans Want.” The New York Times Opinion Available at https://www.nytimes.com/2018/10/31/opinion/congress-midterms-public-opinion.html

Johnson, Matthew L. and Isreal S. Kline (2020). “The Ethics of Lobbying.” In Political Communication Ethics: Theory and Practice (ed. Peter Loge), Rowman & Littlefield.

Keefe, Josh (April 15, 2017). “Why Is Lobbying Legal? A Brief History of Lobbyists In the US.” International Business Times. Available at: https://www.ibtimes.com/why-lobbying-legal-brief-history-lobbyists-us-2525455

Kimball, David C., Frank R. Baumgartner, Jeffrey M. Berry, Marie Hojnacki, & Beth L. Leech (May 2012). “Who Cares About the Lobbying Agenda?” Interest Groups and Advocacy Vol. 1 No. 1, pp 5-25.

National Museum of American History (n.d.). “Lobbying.” Available at: https://americanhistory.si.edu/democracy-exhibition/beyond-ballot/lobbying

Nichols, Hans (Sept. 30, 2020). “Biden will allow lobbyists to join transition team.” Available at:

https://www.axios.com/biden-transition-ethics-lobbyists-20b87d08-a0ed-4d7f-a950-34efebc024a1.html

Author:

Peter Loge

Project on Ethics in Political Communication

George Washington University

October 27, 2020

Image from the Collection of the U.S. House of Representatives

This case study can be used in unmodified PDF form for classroom or educational settings. For use in publications such as textbooks, readers, and other works, please contact the Center for Media Engagement.

Ethics Case Study © 2020 by Center for Media Engagement is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0