The Center for Media Engagement set out to determine what readers don’t understand about the news process and to show newsrooms how they can build trust by addressing common reader concerns.

We asked readers to explain their questions about news stories and found they wanted newsrooms to do a better job of addressing four main areas:

- Digging deeper into stories.

- Explaining terminology.

- Clarifying why certain voices were included in stories and others were left out.

- Avoiding what readers perceived as journalists’ biased depiction of sources.

The Problem

News organizations are facing a crisis of trust with their audiences.1 Our earlier research2 shows that providing information alongside stories about how and why the stories were done can increase readers’ trust of news outlets.

This study tackles the problem in a new way – by going straight to the readers and asking them to share their questions about the news. The goal of this study, supported by the American Press Institute, is to boost readers’ news literacy, and, ultimately, help audiences identify and trust reliable news.3

Key Findings

What participants wanted to know about the news fell into four major categories. They wanted journalists to:

- Dig deeper into circumstances around the news story or take a more investigative.

- Explain specialized terminology.

- Explain why certain sources were included while others were left out.

- Guard against what the readers saw as bias, which they described as potentially cozy relationships between writer and subject.

Solutions for Newsrooms

Based on the questions raised by our focus group participants, we recommend that newsrooms:

- Provide more context in stories and link to previous coverage.

- Explain key terminology and government or police processes.

- Include a wide range of relevant sources and thoroughly explain source choices.

- Provide a statement of independence, stating lack of relationship with sources.

- Place key information up-front or in a box within the story.

The Study

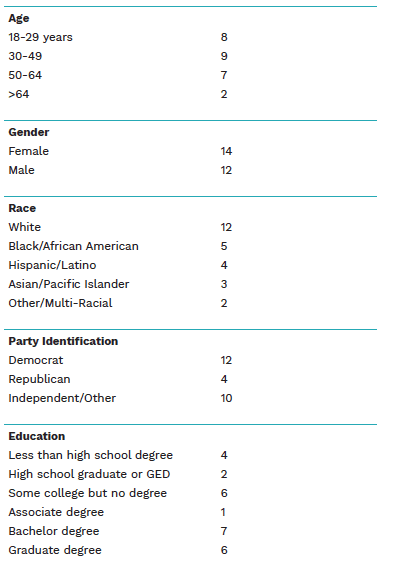

We conducted five focus groups in Texas. A total of 26 participants discussed their questions related to three news stories. The participants were varied in terms of gender, age, race, occupation, education, and political beliefs. Most read news frequently, but about a third of participants read news sometimes or rarely.

In all five groups, we presented participants with three articles chosen from three news organizations: one local newspaper and two newspapers with a national audience. We looked for stories that had general interest and that followed common journalistic standards but also might elicit questions from readers.

We tried to avoid the most polarizing political topics of the day, such as gun control and immigration. The articles were presented in this order:

- A story in a local newspaper about a fatal bus accident where the bus driver may have been impaired by drugs.

- A story in a newspaper with national reach about Wells Fargo Bank rebuilding trust after a series of financial scandals.

- A story in a newspaper with national reach about California considering abandoning the death penalty.

After reading the stories, participants raised questions that fell into four categories. Each participant was assigned a pseudonym that is used here, accompanied by their accurate ages and vocations.

Can You Dig Deeper?

Participants in all five focus groups frequently questioned why the journalists didn’t dig deeper into the stories. They felt the reporting seemed unfinished or superficial.

Many participants wanted the reporter to move beyond the specific news event. For example, after reading a story about Wells Fargo attempting to regain customer trust after a series of scandals, several participants felt the story failed to sufficiently investigate the scandals or link them to a wider network of similar events.

“The article is about Wells Fargo releasing their internal report and what Wells Fargo wants you to know (is what) they’re doing to make things better without any depth on, is this really going to happen, or what the real issues were, or is it just a, you know, puff piece?” asked Oscar, 50, a project manager.

A comment from Liz, 52, a retail warehouse worker, captures the sentiment of several participants, “They ought to be taking them apart. They ought to be going after them like Deep Throat in Watergate.”

The general takeaway is that newsrooms should attempt to fully explore all aspects of the story. This might include explaining background information, providing context beyond the facts of the latest update, and investigating deeper whenever possible.

Can You Break That Down?

Participants also wanted reporters to translate jargon and explain in more detail the procedures mentioned in the story.

After reading the story about a fatal bus crash, participants wanted to know why the bus driver was not arrested. The story reported that a police search warrant indicated she may have been impaired while driving but that she had not been charged with a crime. Participants wanted more explanation of police procedures in this story.

“The Good Samaritan that called the police, you know, and say police got there, right, why they didn’t take her to jail right there?” asked JoJo, 31, unemployed.

Claire, 49, a lawyer, raised a concern about the need to explain jargon after she read the story about Wells Fargo. “And the next paragraph talks about a ‘regulatory knock.’ I think that’s an insider term. That’s not a word, that’s not a term I’m familiar with. So it’s a problem,” she said.

In addition to explaining industry terms, newsrooms should consider detailing the processes and procedures associated with the story.

Why Did/Didn’t You Include This Voice?

Participants also frequently questioned reporters’ decisions to include or exclude specific voices. At times they felt the people quoted in the story seemed irrelevant while more critical voices were left out.

After reading the piece about the death penalty, Toni, 58, questioned why the newspaper included a quote from Pope Francis, “And then at the very end, just kind of popping in, ‘Pope Francis weighed in on the topic.’ And is that relevant?”

Participants were also vocal about the lack of inclusion of what they perceived as important voices. For example, in the bus fatality story, participants did not understand why eyewitnesses to the crash were not quoted. “It says (the bus driver) reacted to passenger warnings, but why don’t they talk to the passengers? I’d like to hear a quote from the actual passengers that were there,” said Trudy, 48.

In addition, this lack of inclusion was commonly associated with a perceived imbalance in the reporting that at times raised suspicion. In the story about Wells Fargo, for example, readers wondered why the bank’s customers were not quoted.

“Like I wonder now if the relationship between the reporter and the bank Wells Fargo – because one thing I noticed is there’s absolutely no quotes in here from anyone outside of the Wells Fargo system. Like there’s no quotes from customers,” said Preston, 22, a college student.

It’s important for newsrooms to include a variety of voices in the story and, perhaps more importantly, to explain why certain voices were chosen and why others were left out or unavailable.

Is This Biased?

More generally, participants raised questions about what they perceived as bias in the stories. These questions centered on the journalists’ motivations, possible affiliation with the subject of the story, and overall angle. As Tim, 46, a consultant, put it: “Well, I’m a news junkie. So I read a lot of news. And I’m always looking for underlying motive if there is any.”

Some participants felt the story about Wells Fargo was one-sided because it focused too much on how the bank had improved. Alex, a 20-year-old college student, asked:

And how far does their history go back?… Do they have a mutually beneficial relationship? Are they consistently against each other? Based on this article, I’d assume they’re actually on good terms. Because this article is pretty much saying, “Look at Wells Fargo. They’re trying to improve.” And it’s not giving any outside perspective.

Similarly, participants questioned why the reporter for the death penalty piece included certain information like the annual number of people executed and a list of the states that execute the most prisoners. This information made Amy, 47, an office manager, feel as if the reporter wanted the reader to oppose the death penalty. “Just the research that he did, the statistics that he gave…pretty much solidified that for me… I think that he chose these statistics just more or less to sway,” she said.

To guard against perceived bias, newsrooms should consider providing a statement of independence, stating a lack of relationship with story sources. Newsrooms could also clarify key information about how and why the story was reported up-front or in a box within the story.

Methodology

We recruited participants for the focus groups in two ways. For the first focus group, we recruited five University of Texas students from two classes, whose professors agreed to award extra credit for participation in the study. For the remaining four focus groups, we recruited 21 non-undergraduate adults from the Austin and Dallas areas. These participants were paid $10 for their time plus $5 to reimburse them for parking fees.

In Austin, we contacted civic and political organizations, religious organizations, and other community groups.4 We approached patrons of the Austin Public Library, where the focus groups were held, and worshipers leaving Sunday church services. We posted about the study on Reddit, Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and NextDoor. We also posted fliers around the Austin area, inviting people to participate.

In Dallas, we held a focus group at Literacy Instruction for Texas (LIFT), which prepares adults to take the GED high school equivalency exam. Participants at LIFT included staff members and students.

The three news stories participants read came from three news outlets chosen because they provide quality news from a mix of local and national outlets. The national outlets we chose are trusted by members of the public who rank as relatively middle-of-the-road ideologically.5

The focus groups each took about 90 minutes and were video recorded and transcribed. At each focus group, we asked participants to read each story, and then we asked a series of questions, such as “What questions did you have about the reporting or writing of this story?” We read through the transcripts multiple times to find commonalities in what participants were saying.

Participant Demographics

SUGGESTED CITATION:

Wilner, Tamar, Montiel Valle, Dominique A., and Chen, Gina Masullo. (2019, October). What people want to know about the news. Center for Media Engagement. https://mediaengagement.org/ research/what-people-want-to-know

- Knight Foundation. (2018, June 20). Perceived accuracy and bias in the news media. Retrieved from https://knightfoundation.org/reports/perceived-accuracy-and-bias-in-the-news-media [↩]

- Chen, G.M., Curry, A., & Whipple, K.N. (2019, February). Building trust: What works for news organizations. Center for Media Engagement. https://mediaengagement.org/research/building-trust [↩]

- Rosenstiel, T., and Elizabeth, J. (2018, May 9). Journalists can change the way they build stories to create organic news fluency. American Press Institute. https://www.americanpressinstitute.org/publications/reports/white-papers/organic-news-fluency/ [↩]

- We approached 29 religious organizations, 25 civic and political organizations, 13 parenting groups, 10 ethnic and cultural groups, eight instructional centers for the GED high school equivalency exam, seven sports and social clubs, five volunteer groups, two veterans’ groups and a rotary club. [↩]

- Data analysis by Michael Kearney, from the data set collected for: Kearney, M. W. (2017). Trusting News Project report 2017. Reynolds Journalism Institute. https://www.rjionline.org/reporthtml.html. We do not name the newspapers because the intent is to generate questions readers may have about typical news stories in general, not to scrutinize particular news organizations. [↩]