SUMMARY

Social media play an essential role in shaping public opinion and keeping citizens informed. But how well does the American public understand the workings of major platforms like Facebook and Google? To find out, the Center for Media Engagement fielded a survey in August of 2020 and asked 1,010 U.S. adults to answer questions about the platforms.

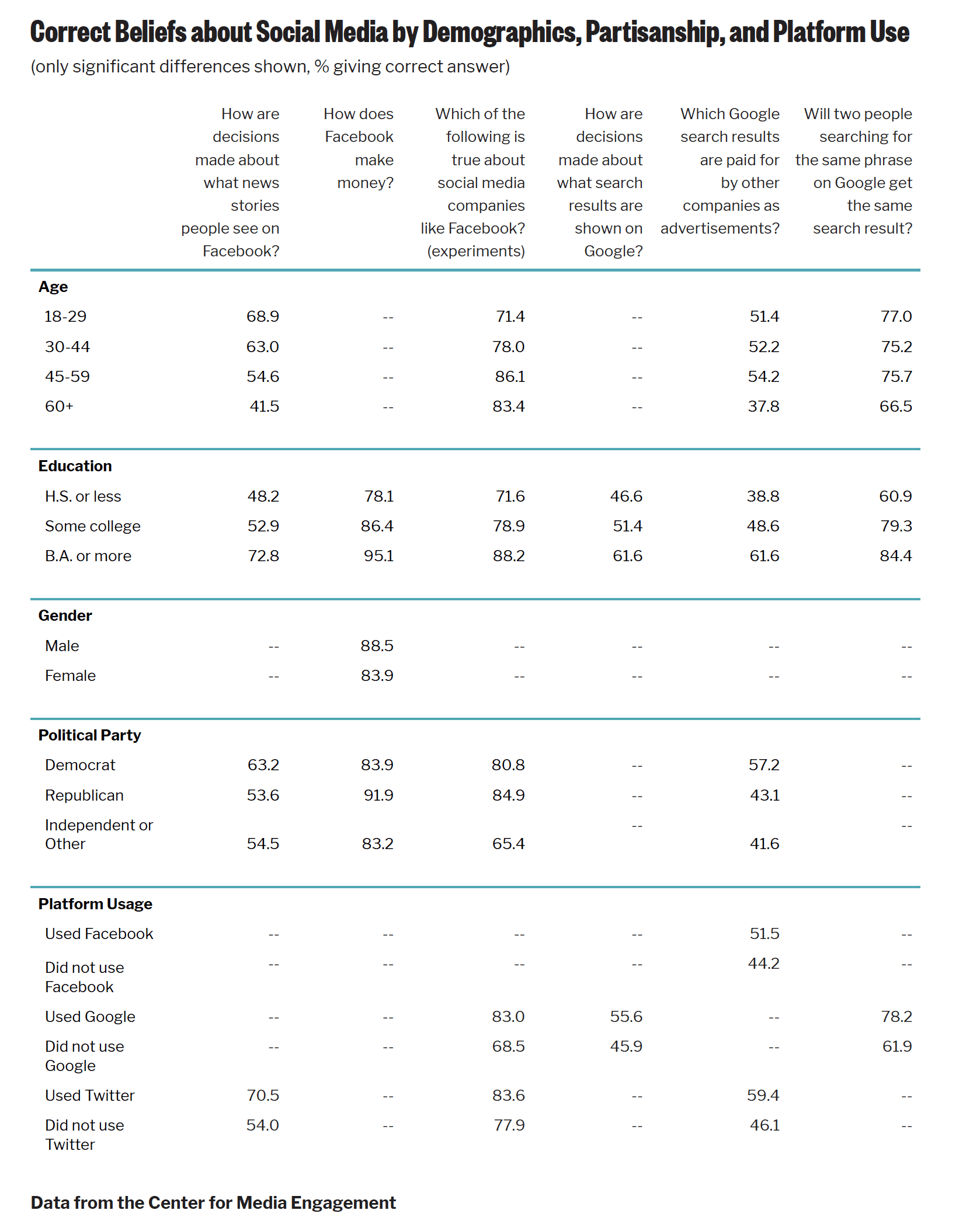

The questions covered topics such as how Facebook and Google make money, how they prioritize content, and whether people searching for the same keywords on Google always get the same search results (for a summary of the questions and responses, see the tables at the end of the report). The results revealed important gaps in the public’s understanding of how Facebook and Google work and showed how these gaps differ by people’s demographics, partisanship, and platform use.

FINDINGS

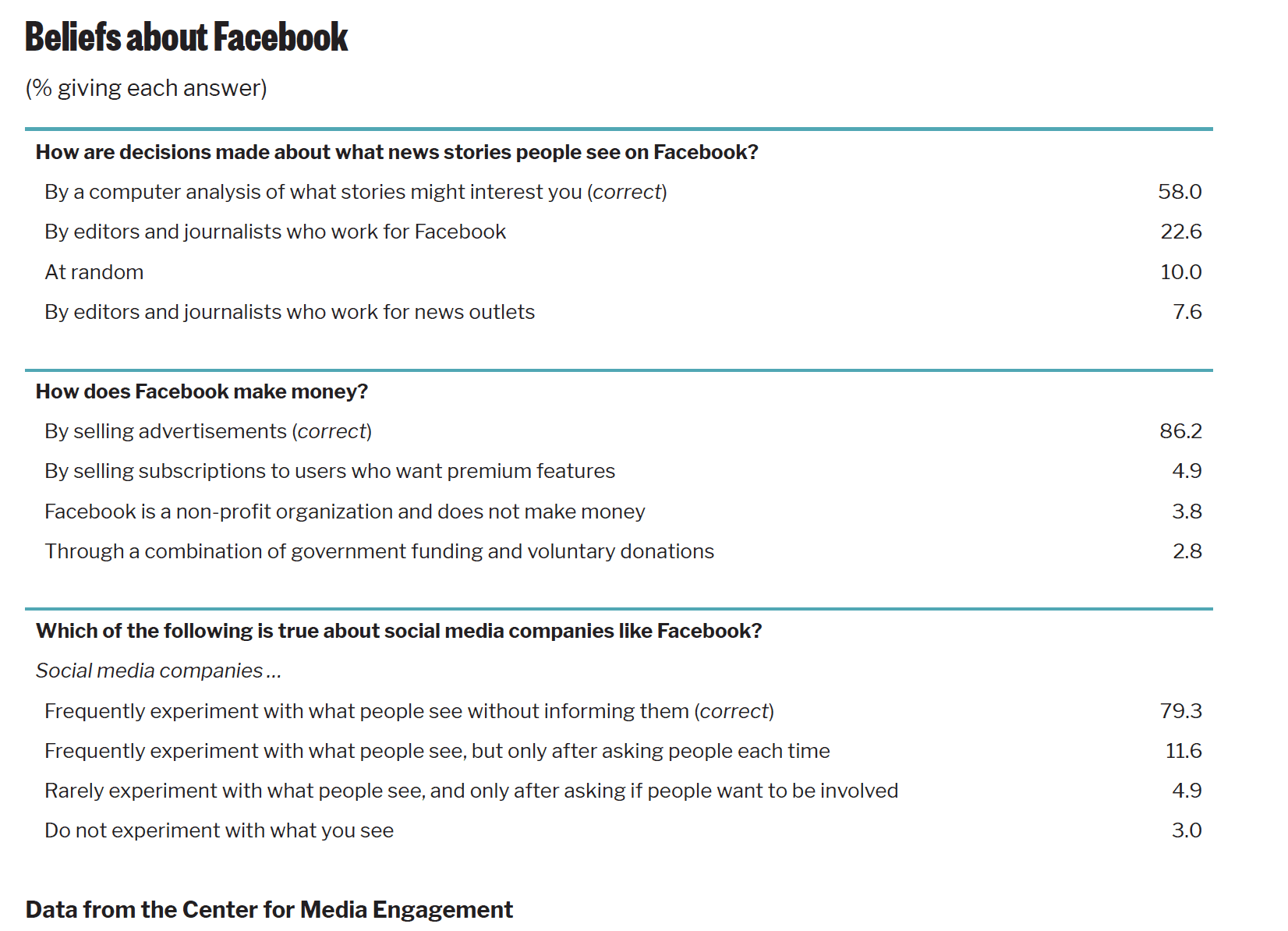

Beliefs about Facebook

Around six in ten respondents (58.0%) knew that decisions about what news stories people see on Facebook are made by a computer analysis of stories that might be of interest. Nearly a quarter of the public (22.6%) thought that these decisions are made by editors and journalists working for the company.

In terms of the business model, most respondents (86.2%) knew that Facebook makes money by selling advertisements.

Nearly eight in ten respondents (79.3%) knew that social media companies like Facebook frequently experiment with the content people see without informing them. Only 11.6 percent thought that experimentation happens frequently, but that platforms like Facebook ask people for their permission first.

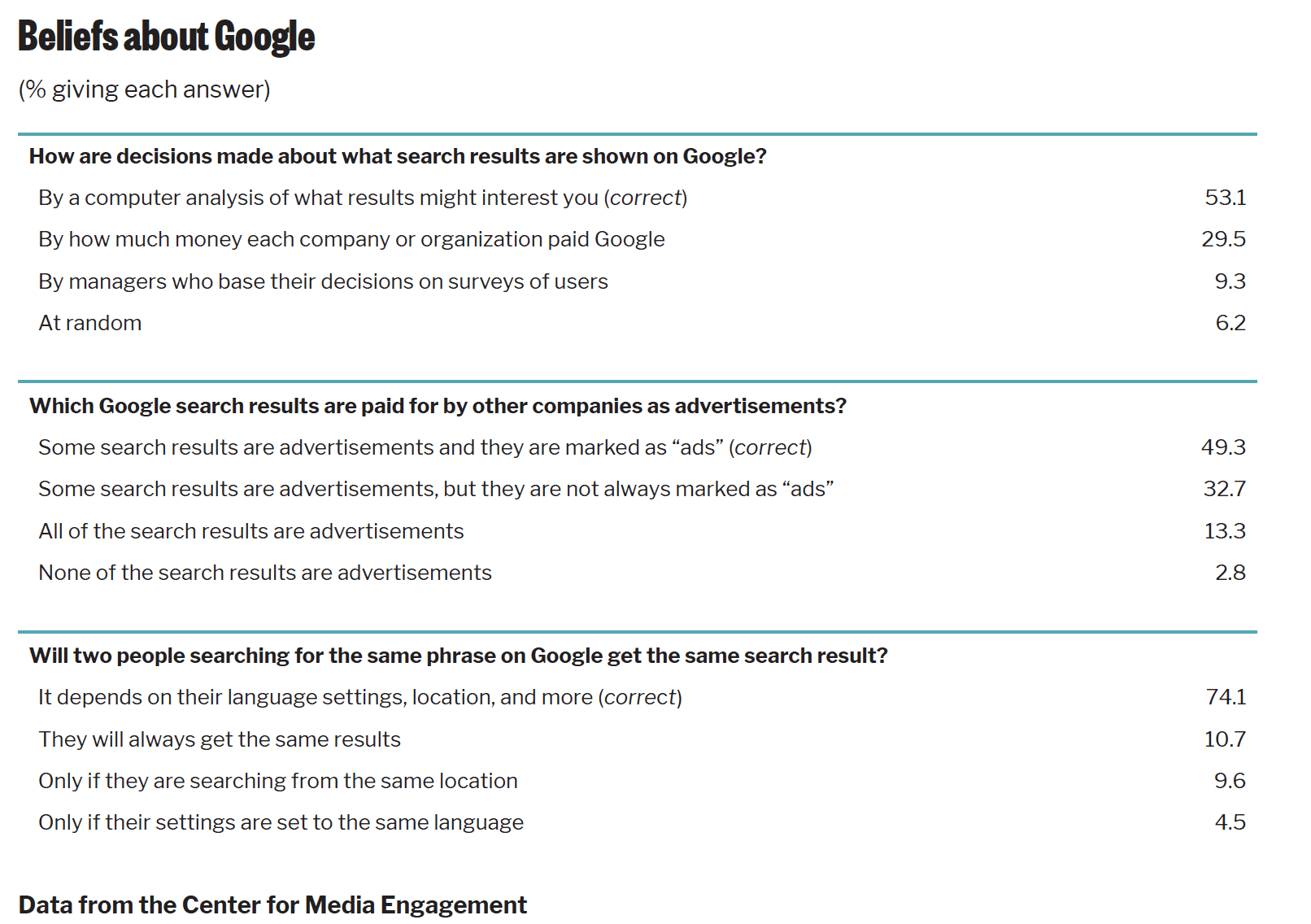

Beliefs about Google

Just over half of the respondents (53.1%) knew that decisions about what search results are shown on Google are made by a computer analysis of what results might be of interest. Three in ten (29.5%) thought that the decisions are determined by how much money companies and organizations pay Google.

Nearly half of the respondents (49.3%) knew that some Google search results are advertisements and that they are marked as “ads.” Nearly a third (32.7%) thought that advertisements on Google are not always marked as ads. And just over one in ten (13.3%) thought that all of Google’s search results are advertisements.

Three-fourths of respondents (74.1%) understood that two people searching for the same phrase on Google may not get the same result because of their language settings, location, and other factors. Only 10.7 percent thought that two people searching for the same phrase will always get the same results.

Demographic Differences

We looked at whether there were differences in the types of people who knew about how social media works. In the following section, we report only on the demographic factors of age, education, and gender, and only where there were statistically significant differences in what people knew.

When it came to age, there were significant differences in levels of knowledge. Older respondents were less likely to know how decisions are made about the news people see on Facebook, how Google indicates paid advertisements in search results, and whether two people searching on Google will get the same result. For one question, however, older respondents were better informed. When asked whether social media companies like Facebook obtain explicit consent for conducting experiments each time, older respondents were more likely to give the correct answer than their younger counterparts.

Education mattered across the board; more educated respondents had a better understanding of how the platforms work relative to those with less education.

In most cases, men and women were equally likely to offer the correct response. Only for one question — how does Facebook make money? — were men slightly more likely to provide the correct answer than women.

Political, Platform Use Differences

In the following section, we report only on political and platform use factors where there were statistically significant differences in what people knew.

Partisans differed in their knowledge about platforms in several instances. Democrats were more likely than Republicans and Independents to know that algorithms make decisions about the news stories people see on Facebook. They also were more likely to know that ads are labeled in Google search results.

Republicans were more likely than Democrats and Independents to know how Facebook makes money and that experimentation happens on platforms like Facebook without asking users for their permission. Democrats were also more likely than Independents to understand how experimentation works on the platforms.

Users of Facebook, Google, and Twitter performed better than non-users on some — but not all — questions.1

Facebook users were no more likely than non-Facebook users to know the correct answer to the three Facebook-related questions we posed.

Users of other platforms, however, were more knowledgeable about several Facebook-related practices. Twitter and Google users were more knowledgeable than non-users about the common practice of experimenting with what users see on platforms like Facebook. Further, Twitter users were more likely than non-users to know how decisions are made about what content is shown on Facebook.

When it came to Google’s practices, Google users were more knowledgeable than non-users for two of the three surveyed practices. Google users were more likely than non-users to know that search results are driven by algorithms and that two people searching for the same word may see different results, depending on their language settings, location, and other factors.

Facebook and Twitter users were more likely than non-users to understand how ads work on Google. Google users and non-users were similarly informed about how ads work on the search platform.

METHODOLOGY

This survey was conducted between August 4 and 17, 2020 among 1,010 Americans aged 18 and over. Survey funding was provided by the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation as part of our connective democracy initiative. Polling was conducted by NORC at the University of Chicago as part of their AmeriSpeak panel.

Panelists were selected using area probability and address-based sampling and were recruited using mail, telephone, and face-to-face interviews. They were able to complete the study either online (n = 978) or via phone (n = 32). The 95% margin of error for this study, adjusted for the design effect, is +/- 4.09%. The sample is weighted for demographics (age, gender, race/ethnicity, and education) as well as Census division, housing tenure, and other aspects of the sampling design.

The sample was 53.2% female, 66.1% white, 10.1% Black, 15.4% Hispanic, 8.3% other and represented all age groups (29.6% aged 18-29; 25.0% aged 30-44; 25.1% aged 45-59; and 20.2% aged 60 or above), education levels (22.0% high school or less, 42.7% some college, and 35.3% college degree or more), and political orientations (45.5% Democrats; 36.1% Republican; 17.6% Independent or Other, treating those who said that the leaned in favor of a party as partisans).

To determine whether there were significant relationships between the platform belief questions and people’s demographics, partisanship, and platform use, we ran logistic regression analyses for each belief question using the full range of responses (e.g., we included all ages, as opposed to four categories). In addition to the variables included in the chart, we also controlled for whether people indicated that they would/would not consult with outside sources when answering the questions. Only 2.7 percent of respondents said that they would not answer the questions without help from outside sources. This variable was inconsistently related with the knowledge questions. Results were similar if we remove those indicating that they wouldn’t answer the questions without outside help.

SUGGESTED CITATION:

Overgaard, Christian Staal Bruun & Stroud, Natalie Jomini. (March, 2021). What Americans know and don’t know about Facebook and Google. Center for Media Engagement. https://mediaengagement.org/research/what-americans-know-and-dont-know-about-facebook-and-google

- Platform usage was measured by asking respondents whether they had used each of the three platforms in the seven days leading up to the survey. [↩]