A July 2020 fundraising email for Marco Rubio for Senate sent from the Republican fundraising platform WinRed compared “cancel culture,” a phrase that some use to capture public shaming movements on social media, to the possibility that National Football League games might be cancelled in the fall of 2020 because of the COVID-19 pandemic. The email concluded that “the cancel culture must be stopped. And it starts with sports.” The email is noteworthy partially because of its confusing argument. But it does highlight the fact that ethical choices reside in the “smaller” things in political communication—including how we choose to construct our appeals, and how we treat our audiences. The email’s message raises several ethical questions.

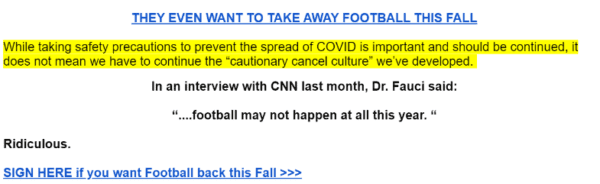

First, it raises the question of when specific quotations are unethically torn from their context and result in possible audience manipulation. The email in question selectively quotes the director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Dr. Anthony Fauci, as saying that “football may not happen this year.” These are the last few words of a longer statement from Dr. Fauci that reads in full, “”Unless players are essentially in a bubble — insulated from the community and they are tested nearly every day — it would be very hard to see how football is able to be played this fall. If there is a second wave, which is certainly a possibility and which would be complicated by the predictable flu season, football may not happen this year” (Sterling and Gupta, June 18 2020). He later expanded on his statement by indicating that the decision to play the professional football season depended on the state of the pandemic, and that the decision was ultimately the NFL’s. (McDaniel, June 24 2020). Yet the email bluntly went on to conclude that “THEY EVEN WANT TO TAKE AWAY FOOTBALL THIS FALL” (emphasis in original). The email does not indicate who “they” are (Dr. Fauci heads a federal agency and has no say over sports leagues). Dr. Fauci’s comments were about the safety of playing, not its legality, a position he later reinforced.

Second, the email asks supporters to sign a petition, the link to which leads to a page asking for donations. There is no obvious petition. Finally, the email equates “cancel culture” with cancelling large events to protect public health. “Cancel culture” in today’s parlance means something different than cancelling an event. Conservative commentator Ross Douthat defines cancel culture as “an attack on someone’s employment and reputation by a determined collective of critics, based on an opinion or an action that is alleged to be disgraceful and disqualifying” (Douthat, July 14 2020). Examples of this sort of social ostracism include comedians Kevin Hart being “cancelled” for homophobic segments in his standup comedy and Louis C.K. being “cancelled” after a number of allegations of sexual misconduct (Romano, 2019).

This email’s choice to conflate social or cultural “cancelling” with cancelling events brings up the larger issue of advocates using buzzwords that may be poorly understood to advance a political position or campaign. What are the ethical concerns with trying to get this sort of rhetorical leverage with your persuasive appeals? Cancelling the 2020 NFL season would be frustrating for fans, and have a significant financial impact on everyone from team owners to beer vendors. Television networks alone could lose more than $2 billion, with NFL games accounting “for 41 of the 50 top-rated telecasts of any kind in 2019” (Strauss, July 2 2020). What should be done about planned sporting events is a question with which leagues around the world are wrestling during the global outbreak.

But conflating the different sorts of cancelling activities has its cost. Whether or not efforts at “cancelling” someone by forcing them to lose their job or public platform is ethical is an important question, one being debated both on and offline (see for example Alexander, July 14 2020). But those efforts are very different from cancelling large public gatherings or sporting competitions.

In this persuasive message, Senator Rubio is attempting to raise money by using one word to equate two things with different meanings – offline public gatherings and online political behavior. What “cancel” means in each case is different, but by putting them in the same context Senator Rubio is painting a larger political picture to argue people should “STAND AGAINST THE LIBERAL MOB” as the webpage to which the petition link takes readers says (WinRed 2020, emphasis in original).

This piece of rhetorical sleight of hand might be effective, since it involves a transference of something incredibly important in politics—emotional valence. One could see a new meaning, and a new importance, in the cancellation of sporting events when this connection is made to something they already feel strongly about, such as social ostracism. Those angry about the possibility of sporting events not taking place might also be angry about attempts to silence the public expression of some political or social views. Other readers might recognize that Senator Rubio is engaging in a bit of clever word play that voters may have come to expect from politicians. Some, however, may not see Senator Rubio’s appeal as wordplay, and may equate cultural criticism with efforts to promote public health and safety. Senator Rubio could be trying to be clever – or he could be trying to deceive would-be donors by using similar words with different meanings in a way that implies they imply the same thing. Even if he doesn’t mean to be deceptive, not everyone might get the joke and many may take him seriously.

Senator Rubio is far from the first or only politician to treat language casually. Candidates of all stripes talk about “socialism,” “Marxism,” “capitalism,” “fascism,” “racism,” and other words often without regard to academic or historical understandings of their meaning. People claim to be “real” Democrats, Republicans, feminists, and more, arguing that the popular understanding of those terms is incorrect and that their personal understanding, if used by others, would lead to correct thinking (and presumably agreement).

In his classic 1946 essay, “Politics and the English Language,” George Orwell wrote that words like “socialism” were used imprecisely to generate political enthusiasm, and that they had effectively lost their meaning because they were used so often by so many people to mean many different things. As Orwell wrote more than 70 years ago, “The word Fascism now has no meaning except in so far as it signifies ‘something not desirable’” (Orwell, 1946). He continued:

Words of this kind are often used in a consciously dishonest way. That is, the person who uses them has his own private definition, but allows his hearer to think that he means something quite different….Other words use in variable meanings, in most cases more or less dishonestly, are: class, totalitarian, science, progressive, reactionary, bourgeois, equality. (Orwell 1946)

A recent example of this is Republican Senator John Cornyn’s tweet that the “radical left” has a “socialist, anarchist agenda” (Cornyn 2020). Socialism in the U.S. generally implies greater government control and authority, while anarchism is the absence of central government authority – both cannot logically be on the same agenda. Senator Cornyn’s tweet is meant to inspire action, not increase understanding. Other examples across the political spectrum abound – including liberals comparing President George W. Bush to Hitler, and arguing the now-Senator Mitt Romney was the most conservative Republican presidential nominee since Goldwater (Graham, 2016).

Orwell’s position makes a critical assumption: that words have specific, agreed upon, meanings and that we ought to stick to those meanings. As he writes “What is needed above all is to let the meaning choose the word, and not the other way around” (Orwell 1946). There is a meaning to which the word attaches, and good writers look at the idea and find the right word to describe it. For Orwell, bad political writing on the other hand focuses on the words rather than the ideas. When we say “socialism really means…” or “cancel culture is not the same as cancelling sports” we imply there that the words “socialism” and “cancel” have specific, fixed meanings that advocates should stick to. We will point to dictionaries or public commentary (as this case study does) for “real” definitions. We assert that language is connected to something outside of language – that there is a “cancel culture” or “conservative” separate from our use of the terms. This question of whether there is a knowable social or political reality outside of our own description of it has been a topic of heated debate for thousands of years. As early as Plato and the sophists, philosophers wrestled with the nature of the relationship between words, ideas, and the world in which we live.

If there is no fixed or constant meaning for important words such as “cancel,” “socialist,” or “fascist” (or anything else) can we treat the words as if they mean whatever we want? If socialism didn’t exist before people invented it and stuck a word on the idea, it may not matter if we get the idea “wrong.” It may not even be possible to get something wrong that doesn’t exist beyond or our own word for it. If meaning is in the mouth (or email or tweet) of the user, then what Senator Rubio said is ethical because he said it.

Others argue that using words correctly matters, even if they do not have fixed meanings. The conservative scholar and former aide to presidents Bush and Reagan, Peter Wehner, wrote, “Democracy requires that we honor the culture of words” (Wehner 2019, p. 99). Definitions may not be eternally fixed, but there can be general and shared understandings of what specific words mean. When someone says “table” we may have different pictures in our heads but we largely agree it is a piece of furniture with a flat top at which we sit to do things like eat and read case studies. Words such as “socialist” or “cancel culture” might similarly conjure different details for each of us, but we may be able to broadly agree on what the terms mean.

The arguments for decreasing ambiguity and increasing precision are both deontological – it’s the right thing to do – and pragmatic. Without a shared general agreement about what the words mean it can be difficult to have a reasonable political debate. For many, one should be precise with one’s language for the same reason one shouldn’t lie: both are deceptive and both are wrong. For others, if we dilute the meaning of words when something we can all agree is bad is happening – fascism for example – it can be difficult to draw attention to it if we have used the term “fascism” imprecisely in the past. If we call a conservative leader with whom we disagree a “fascist” what do we call a leader with even more violent behavior that limits freedom and constrains democracy? As David Graham wrote in The Atlantic in 2016, “Once you’ve already used all of these insults once before, they start to lose their sting.” We risk becoming the voter who cried wolf; we shout about the threat to get attention so often, that when there is a real threat no one believes us.

If this is right, then politicians have an obligation to make their meaning as clear as they can, and to use words in ways that most of their constituents understand. For example, Senator Rubio has an ethical obligation not to conflate cancelling sporting events and attacking political views. Similarly, those who use the terms “socialist” “Marxist” “fascist” “anarchist” and so forth should take care to use the terms as they are used in political science or economics, which is where the terms originated rather than just as buzzwords the meaning of which does not matter beyond “something not desirable.”

Questions for Discussion:

- What ethical concerns or conflicts are raised by Senator Rubio’s email campaign?

- What are some of the ethical obligations that those arguing about political issues have? How must they use, and not use, language?

- Do you agree that most important words have a limited range of meanings? Is anything gained by creatively applying some charged words to new people or new phenomena?

- How should communicators go about challenging those who incorrectly use established terms?

Further Reading:

Alexander, Ella https://www.harpersbazaar.com/uk/culture/a33296561/cancel-culture-a-force-for-good-or-a-threat-to-free-speech/

Cornyn, John (July 13, 2020) Tweet https://twitter.com/JohnCornyn/status/1282790539495198720?s=20

Douthat, Ross. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/07/14/opinion/cancel-culture-.html

Goldman, Tom. https://www.npr.org/2020/06/11/874311586/bubbles-and-empty-seats-pro-sports-forge-ahead-with-comebacks-despite-the-pandem

Graham, David A. (August 3, 2016) The Democrats Who Cried Wolf. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2016/08/the-democrats-who-cried-wolf/493928/

McDaniel, Mike https://www.si.com/college/virginiatech/football/dr-anthony-fauci-clarifies-comments-on-football-being-played-this-fall

Orwell, George (1946) “Politics and the English Language” https://www.orwellfoundation.com/the-orwell-foundation/orwell/essays-and-other-works/politics-and-the-english-language/

Romano, Aja (December 30, 2019). Why We Can’t Stop Fighting about Cancel Culture. Vox. https://www.vox.com/culture/2019/12/30/20879720/what-is-cancel-culture-explained-history-debate.

Sterling, Wayne and Dr. Sanjay Gupta. (June 18, 2020) “Football may not happen at all this year, Fauci warns.” CNN Online. https://www.cnn.com/2020/06/18/us/football-happen-fauci-spt-trnd/index.html

Strauss, Ben. https://www.washingtonpost.com/sports/2020/07/02/tv-networks-nfl-season-coronavirus/

Wehner, Peter. (2019) The Death of Politics. New York: HarperOne.

Williams, Brenna. CNN. https://www.cnn.com/2017/08/17/politics/tbt-clinton-grand-jury-testimony/index.html

Author:

Peter Loge

Project on Ethics in Political Communication

George Washington University

September 28, 2020

This case study is supported by funding from the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. It can be used in unmodified PDF form for classroom or educational settings. For use in publications such as textbooks, readers, and other works, please contact the Center for Media Engagement.

Ethics Case Study © 2020 by Center for Media Engagement is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0