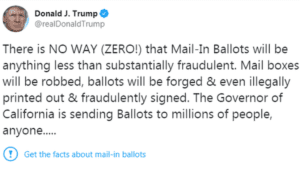

Twitter made both headlines and enemies after labeling a tweet from President Donald Trump as containing “potentially misleading information about voting processes” (Wong, 2020). By claiming there was “NO WAY that Mail-In Ballots will be anything less than fraudulent” and that the 2020 presidential race would “be a Rigged Election,” the President violated Twitter’s Civic Integrity Policy implemented only days before (Twitter 2020). The policy prohibits any interference with elections or other civic processes, such as the census, major referenda, and ballot initiatives. Violations include “posting or sharing content that may suppress participation or mislead people about when, where, or how to participate in a civic process” (Twitter, 2020). Twitter concluded discouraging users from voting by mail, despite growing health concerns over in-person voting amid a global pandemic met these criteria and flagged Trump’s tweet. They added a label advising users “get the facts about mail-in ballots,” including that “fact-checkers say there isn’t any evidence that mail-in ballots are linked to voter fraud” (Twitter 2020). The tech giant’s CEO, Jack Dorsey, once claimed that it “would be dangerous… to be arbiters of truth” (Burch, 2018). The decision to flag a tweet from the President of the United States—and one of the site’s most influential users—signals Twitter may be changing that stance. As social media companies like Twitter are increasingly bombarded by misinformation on their platforms, citizens, news organizations, and state actors alike continue to express concern over the role of big tech in balancing free speech and rampant falsehoods.

By navigating this uncharted virtual terrain, Twitter is potentially setting a standard for how U.S.-based tech companies will define the limits of free speech on their platforms in the face of digital misinformation. Twitter’s decision was met with mixed reviews. Only moments after Twitter launched the fact-check label, conservative users, including the President himself, took to their timelines. Trump wrote: “Twitter is completely stifling FREE SPEECH, and I, as President, will not allow it to happen!” Conservative Twitter users fear the company’s policies could be masking an anti-conservative agenda, citing anti-Trump tweets from “Yoel Roth, who oversees site integrity” as proof (Wong, 2020). Trump Campaign Advisor, Brad Parscale, blamed what he called the “fake news media” and fact checkers at private companies like Twitter who are simply a “smoke screen” to give “obvious political tactics some false credibility” (Wong 2020). Founded upon the “core tenets of freedom of expression,” Twitter has fervently defended its Civic Integrity Policy as a necessary means to fight “attempts to undermine the integrity of our service.” Spreading harmful misinformation, according to Twitter, is one such maneuver (Twitter, 2020). As a private social media company, Twitter is not beholden to the First Amendment, which only prohibits Congress from restricting free speech (Phillips, 2020). However, the public and policy makers are increasingly demanding companies like Twitter defend if and how their decisions relating to speech online are protecting or harming the public interest.

By navigating this uncharted virtual terrain, Twitter is potentially setting a standard for how U.S.-based tech companies will define the limits of free speech on their platforms in the face of digital misinformation. Twitter’s decision was met with mixed reviews. Only moments after Twitter launched the fact-check label, conservative users, including the President himself, took to their timelines. Trump wrote: “Twitter is completely stifling FREE SPEECH, and I, as President, will not allow it to happen!” Conservative Twitter users fear the company’s policies could be masking an anti-conservative agenda, citing anti-Trump tweets from “Yoel Roth, who oversees site integrity” as proof (Wong, 2020). Trump Campaign Advisor, Brad Parscale, blamed what he called the “fake news media” and fact checkers at private companies like Twitter who are simply a “smoke screen” to give “obvious political tactics some false credibility” (Wong 2020). Founded upon the “core tenets of freedom of expression,” Twitter has fervently defended its Civic Integrity Policy as a necessary means to fight “attempts to undermine the integrity of our service.” Spreading harmful misinformation, according to Twitter, is one such maneuver (Twitter, 2020). As a private social media company, Twitter is not beholden to the First Amendment, which only prohibits Congress from restricting free speech (Phillips, 2020). However, the public and policy makers are increasingly demanding companies like Twitter defend if and how their decisions relating to speech online are protecting or harming the public interest.

For example, Twitter previously declined requests from former Congressman Joe Scarborough that the site remove/flag tweets in which the President implied that Scarborough had murdered a former aide, Lori Klausutis. Although arguably misleading, these tweets from the President did not violate any existing policy and therefore warranted no action. While users may call for a post to be taken down because it is deceitful, misleading, or otherwise unethical, tech companies follow stringent guidelines, often crafted to preserve profit margins. Thus, tech company employees are not asking “is this post ethical” but rather “has a rule been broken?” and “is it a clear-cut violation, or can the post be viewed multiple ways?” (Newton, 2020). Employees creating platform-defining policies must “try to write the rule narrowly, so as to rule in the maximum amount of speech, while ruling out only the worst” (Newton, 2020). With the presumption against ruling too much speech out of bounds, some could argue the platform has historically protected misinformation—even when it stems from hugely influential voices. The recent change is seen by some as an attempt to right that ethical wrong.

Yet many are concerned about the ability of large companies like Twitter to place undue restrictions on an individual’s right to free speech and expression. European human rights lawyer Marko Milanovic argues the right to speech guaranteed in the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution “has no applicability whatsoever to restrictions by private actors” or actors in other countries, so the work to fight misinformation may require states and private entities to adhere to a common set of guidelines similar to international human rights law (Milanovic, 2020). With millions of users across the globe, online platforms like Twitter represent some of the largest public forums available, making the suppression of speech a valid ethical concern. How should such companies balance the fight against misinformation with democratic goals of increasing lines of communication among citizens of various nations? Some would argue these decisions regarding the limits of speech on social media platforms “that potentially involve balancing between competing human rights” should “be made by states, and be subjected to public scrutiny” (Milanovic, 2020). “The rules of speech for public space,” says UN Special Rapporteur, David Kaye, “should be made by relevant political communities, not private companies that lack democratic accountability and oversight” (Milanovic, 2020). Yet different countries have different understandings of what constitutes hate speech, legal speech, and misinformation, placing further obstacles in the way of unified legislation that affects social media platforms that feature speech across national boundaries.

Efforts to combat growing misinformation have been adopted by a number of platforms and publications. The Washington Post, for example, implemented their own fact-checking system in 2007 to provide a public resource verifying the truth or falsity of statements by prominent public figures and political actors (Kessler, Rizzo, & Kelly, 2020). Critics of the hands-off approach to moderation, including Facebook’s policy not to subject politicians to third-party-fact checking, say a lack of regulation or fact-checking is unethical. It provides “politicians a pass to spread misinformation to millions instantly” through their highly influential “network effect” (The Thread, 2020). So while a 2018 poll from Pew Research found that the majority of Americans favored protecting their freedoms of speech online over efforts against misinformation, those surveyed were increasingly open to action by private over public actors, creating an opening for tech giants to act. With over half of U.S. adults supporting actions by tech companies to restrict misinformation online “even if it limits the public’s freedom to access and publish information,” Twitter may find their current approach to addressing misinformation online broadly popular (Mitchell, Greico, & Sumida, 2018).

Ultimately, the goal for Twitter is laudable and simple; according to a spokesperson it is “to make it easy to find credible information on Twitter and to limit the spread of potentially harmful and misleading content” (Roth & Pickles, 2020). From banning political ads in 2019 to flagging the President of the United States for misleading tweets in 2020, Twitter’s ever-evolving moderation policies will continue to define the way users consume and share information online.

Discussion Questions:

- What ethical values are in conflict in the debate over fact checking or labelling Trump’s tweets as containing misinformation?

- Should the President be held to different standards than normal social media users when it comes to bombastic or potentially misinformed tweets or opinions? Why or why not?

- What political speech should be subject to fact checking on social media? Whose job should it be to address the truthfulness of content on social media?

- What’s more dangerous: misinformation or censorship? Is there a way to address one concern without promoting the other?

Further Information:

Burch, S. (2018, August 20). “Twitter Shouldn’t be ‘Arbiters of Truth,’ Says CEO Jack Dorsey.” The Wrap. Available at: https://www.thewrap.com/twitter-arbiters-truth-jack-dorsey/

Cummings, W. (2020, May 28). “Trump fuming at social media over Twitter fact check. How platforms handle misinformation differently.” USA Today. Available at: https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/politics/2020/05/27/social-media-platforms-different-approaches-misinformation/5265288002/

Kessler, G., Rizzo, S., & Kelly, M. (2020, July 13). “President Trump has made more than 20,000 false or misleading claims.” The Washington Post. Available at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2020/07/13/president-trump-has-made-more-than-20000-false-or-misleading-claims/

Milanovic, M. (2020, April 14). “Viral Misinformation and the Freedom of Expression: Part III.” European Journal of International Law. Available at: https://www.ejiltalk.org/viral-misinformation-and-the-freedom-of-expression-part-iii/

Mitchell, A., Greico, E., & Sumida, N. (2018, April 19). “Americans Favor Protecting Information Freedoms Over Government Steps to Restrict False News Online.” Pew Research Center. Available at: https://www.journalism.org/2018/04/19/americans-favor-protecting-information-freedoms-over-government-steps-to-restrict-false-news-online/

Newton, C. (2020, May 27). “Why Twitter is labeling Trump’s tweets as “potentially misleading” is a big step forward.” The Verge. Available at:

https://www.theverge.com/interface/2020/5/27/21270556/trump-twitter-label-misleading-tweets

Phillips, A. (2020, May 29). “No, Twitter is not Violating Trump’s Freedom of Speech.” The Washington Post. Available at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2020/05/29/no-twitter-did-not-violate-trumps-freedom-speech/

Roth, Y. & Pickles, N. “Updating our approach to misleading information.” Twitter. Available at https://blog.twitter.com/en_us/topics/product/2020/updating-our-approach-to-misleading-information.html

The Thread. (2020, June 2). “Should Politicians be Exempt from Fact-Checks on Facebook?” Available at: https://www.thethreadweekly.com/news/fact-checking-politicians-facebook

Twitter. (2020 May). “Civic integrity policy.” Available at: https://help.twitter.com/en/rules-and-policies/election-integrity-policy

Wong, Q. (2020, May 27). “Twitter faces conservative backlash for fact-checking Trump’s tweets for the first time.” CNET. Available at: https://www.cnet.com/news/twitter-faces-conservative-backlash-for-fact-checking-trumps-tweets-for-the-first-time/

Authors:

Chloe Young, Dakota Park-Ozee, & Scott R. Stroud, Ph.D.

Media Ethics Initiative

Center for Media Engagement

University of Texas at Austin

October 13, 2020

Images: Clemens Ratte-Polle / CC-BY-SA 3.0 // Twitter Screenshot

This case study is supported by funding from the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. It can be used in unmodified PDF form for classroom or educational settings. For use in publications such as textbooks, readers, and other works, please contact the Center for Media Engagement.

Ethics Case Study © 2020 by Center for Media Engagement is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0