SUMMARY

This report explores a small, yet impactful, way that journalists can connect with misrepresented or stigmatized audiences: using person-centered language, as opposed to stereotypical labels, to describe communities in news articles. The Center for Media Engagement partnered with Resolve Philly, an organization that promotes best practices for equitable and community-based journalism, to survey three often stigmatized groups: people who have experienced homelessness, people with disabilities, and people in recovery from substance use disorder. We found that people who read an article that used person-centered terms for their group (e.g., person with substance use disorder) felt more humanized and trusted the article more than people who read a story with stigmatizing labels (e.g., drug abuser). Based on this work, we recommend that journalists use person-centered language in their reporting.

PROBLEM

The labels journalists choose when describing certain communities, particularly those who are marginalized by society, can evoke negative stereotypes and create public stigma toward these groups. Harmful labels may also isolate communities and make them feel like journalists don’t understand them or serve them well. As an alternative, advocates have called for the use of person-centered or person-first language, but it has yet to be tested how marginalized communities themselves feel about person-centered terms in news. With support from Resolve Philly and Democracy Fund, the Center for Media Engagement addressed this question by soliciting feedback on news articles from three stigmatized groups: people in recovery from substance use disorder, people who have experienced homelessness, and people with a disability.

KEY FINDINGS

- Participants trusted articles that used person-centered terms for their group more than articles that used stigmatizing terms.

- News articles with person-centered terms boosted participants’ group esteem, or their perception that their group was humanized in the story.

- People in recovery from substance use disorder felt more accurately represented by articles that used person-centered terms instead of stigmatizing terms.

- People’s willingness to engage with the news and to share their story with a journalist didn’t vary depending on whether person-centered or stigmatizing terms were used.

- Participants shared that they preferred that journalists use person-centered terms to describe their group in news articles.

IMPLICATIONS

Advocates have suggested that stereotypical labels for marginalized groups emphasize ‘otherness’ and encourage stigma, while person-centered terms put focus on the humanity of every individual first. The results of this report reveal how even these small changes in language have the power to shift attitudes. Person-centered terms bolstered trust in news and helped some groups feel more holistically represented and humanized in news coverage. In order to better connect with stigmatized groups, news organizations should use person-centered language in news articles and engage in conversations with their sources about their preferred terms. To help journalists update dehumanizing language with person-centered terms in new articles, Resolve Philly is pioneering a community-informed style guide planned for release in early 2023.

FULL FINDINGS

Advocates contend that person-centered language highlights the dignity of individuals by defining them not by one aspect of their life, but as a human being first.1 If utilized more frequently by journalists, person-centered terms could communicate respect and act as a better bridge to trust than language that reinforces negative stereotypes. The focus of this report is to test this theory and explore whether person-centered terms can build better relationships between journalists and stigmatized groups.

In this study, we asked three stigmatized groups (people who have experienced homelessness, people in recovery from substance use disorder, and people with disabilities) to share their thoughts about how journalists cover them. Participants read a news article about their group that either used person-centered language (e.g., people with disabilities, people with substance use disorder, or people without housing) or stigmatizing language (e.g., the disabled, drug abusers, the homeless). They then answered questions about how much they trusted the news article and its author, their intentions to engage with the article, and how well the article represented their group.

Trust and Engagement

After reading a news article about their group, we asked people whether they felt that the article “is fair,” “is accurate,” “tells the whole story,” and “can be trusted.”2 Participants who read an article with person-centered terms rated the article as more trustworthy than those who read an article with stigmatizing terms.3

We also examined whether person-centered language could improve participants’ relationship with the journalist who wrote the story. Participants rated a series of statements related to whether they trusted the journalist enough to share their own story with them, such as “I would feel comfortable sharing my personal experiences with this journalist” and “If this journalist wrote an article about my life, I am confident that they would do a good job.”4 There were no significant differences between respondents who read an article with person-centered terms and those who read an article with stigmatizing terms.5

The use of person-centered terms versus stigmatizing labels also did not have an impact on participants’ intentions to take actions related to news engagement, such as sharing the article on social media or talking about the article with others.6

Representation in the News

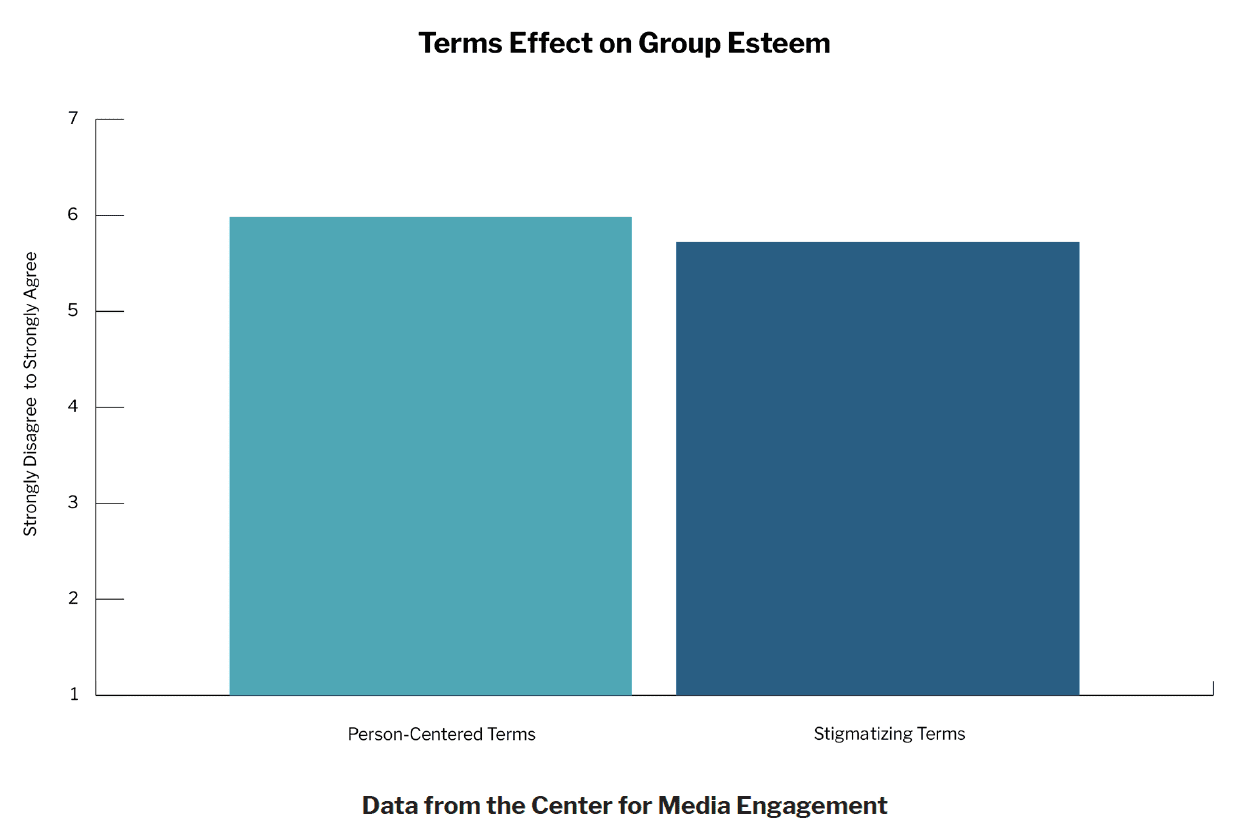

We were interested in whether labeling choices could have an impact on participants’ group esteem, or their perception that the article humanized their group. To measure this, participants indicated whether they agreed or disagreed with statements like “In general, this news article respects people who have [a disability/experienced homelessness/ experienced substance use disorder]” and “In general, this news article presents people who have [a disability/experienced homelessness/experienced substance use disorder] as unworthy.”7

Articles with person-centered terms made participants feel more respected and humanized than articles with stigmatizing labels.8

We also evaluated the impact different terms had on whether participants felt that the news article reflected their group’s true experiences and concerns. In the survey, participants shared whether they thought the article they read “Does a good job of showing what is going on with people like me,” “Is concerned with my interests,” “Is too negative about people like me” and “Is focused on helping people like me.”9

Whether person-centered terms prompted people to think that their group was accurately represented varied by group. People in recovery from substance use disorder felt better understood by articles that used person-centered terms instead of stigmatizing terms. However, participants with a disability and participants who had experienced homelessness did not rate the two versions of the article about their groups differently.10

How People Viewed the Terms Journalists Use

At the end of the survey, we asked people directly about the terms they prefer journalists use when reporting on their group. They were able to select as many terms as they wished and could provide their own terms if none of the available options were sufficient.

In general, participants selected person-centered terms much more often than alternatives. Across all three groups, only person-centered terms garnered more than 50% approval from participants. The most popular terms for each group were “Person who has experienced addiction” (75.6%), “Person in recovery from substance use disorder” (71.1%),

“People with a disability” (84.4%), and “People experiencing homelessness” (71.1%). In contrast, approval of the stigmatizing terms used in our study was much lower; 15.6% selected “the disabled,” 30.8% selected “the homeless,” and 6.7% selected “drug abusers.”

In open-ended responses, participants explained their thoughts about the terms journalists use to describe people and groups. One respondent wrote, “I think the terms journalists use to describe people is important because it can frame how they should be viewed by the reader. They should be assigned terms that respect their dignity as humans and reflect where they are at now in life.”

Another explained their preference for person-first language this way: “I think that when journalists use the term disabled people it makes the disabled part more dominant than the people part. I enjoy being a person first and has a disability second. I am still soul, mind, and body. I am not just my disability!!”

Some participants wrote that they thought stigmatizing labels erased complexity and discounted the societal forces behind substance use disorder and homelessness. One respondent shared: “I think the term drug user is an over simplification of what is going on with the person. Addiction is a disease, not a choice. I think I would like to see ‘a person suffering from addiction’ or something along those lines.” Similarly, another respondent said: “I think the terms used are pretty fair, but the term homeless sounds like a bum living on the street with a whiskey bottle in their hand. People without homes sometimes dress well and take care of themselves and are able to pull off this illusion of not being homeless. The cost of housing is high and it’s tough for a lot of people to afford the rising prices.”

One participant noted that the terms used in news articles can be an indicator of how deeply the journalist connected with and listened to the community: “I think you can tell a lot about the character and credibility of journalists and their publications based on how they describe people. If you describe someone as ‘wheelchair-bound,’ for example, I will doubt your credibility because that term has not been acceptable for a long time. It shows me that they’ve done little to no investigation or keeping up with the issues associated with those people, nor listened to their point of view.”

A smaller number of people expressed concern about the focus on specific terminology, sharing that person-centered terms may confuse people or downplay the intensity of the experiences of these groups. As one respondent wrote: “ I think it’s important to use terms that everyone understands, so common terms like ‘homeless’ is perfectly fine. When you start to use more ‘PC’ language, the general public might not understand the words being used. The problem needs to be solved, not the words used to define it.” Another said: “I think soft language often makes too light of problems and homeless means home less, no shelter, nothing, nowhere to be safe and warm for too long, no stability.”

At the same time, even some skeptical respondents still recognized the need to communicate respect for people in news articles. One respondent wrote, “I think they can be respectful without sugar coating it. Beating addiction is tough. But using flowery language isn’t going to help anything. At the same time, you don’t want to disrespect someone who has put effort into their recovery.”

Another shared, “I think balance is necessary. Don’t go woke with it, but keep it respectful. Treat it as a characteristic but not what defines the person.”

It is also clear from the responses that there are other term characteristics outside of person-centeredness that may also matter to stigmatized groups. For example, the most popular term among people who had experienced homelessness was “People experiencing homelessness” (71.05%), but other person-centered terms, such as “People without homes” (24.56%) did not perform as well. It’s possible that the word “experiencing” was particularly important for some people, as it avoids portraying homelessness as a permanent or defining trait. As one respondent explained, “Calling people who are experiencing homelessness that and other like phrases simultaneously allows these people to maintain their dignity, and it helps to show that homelessness is a temporary situation. These types of phrases also shows that homelessness can occur to anyone at any time.”

Given the variation in responses, journalists should consider asking their sources about their term preferences during the course of their reporting.

METHODOLOGY

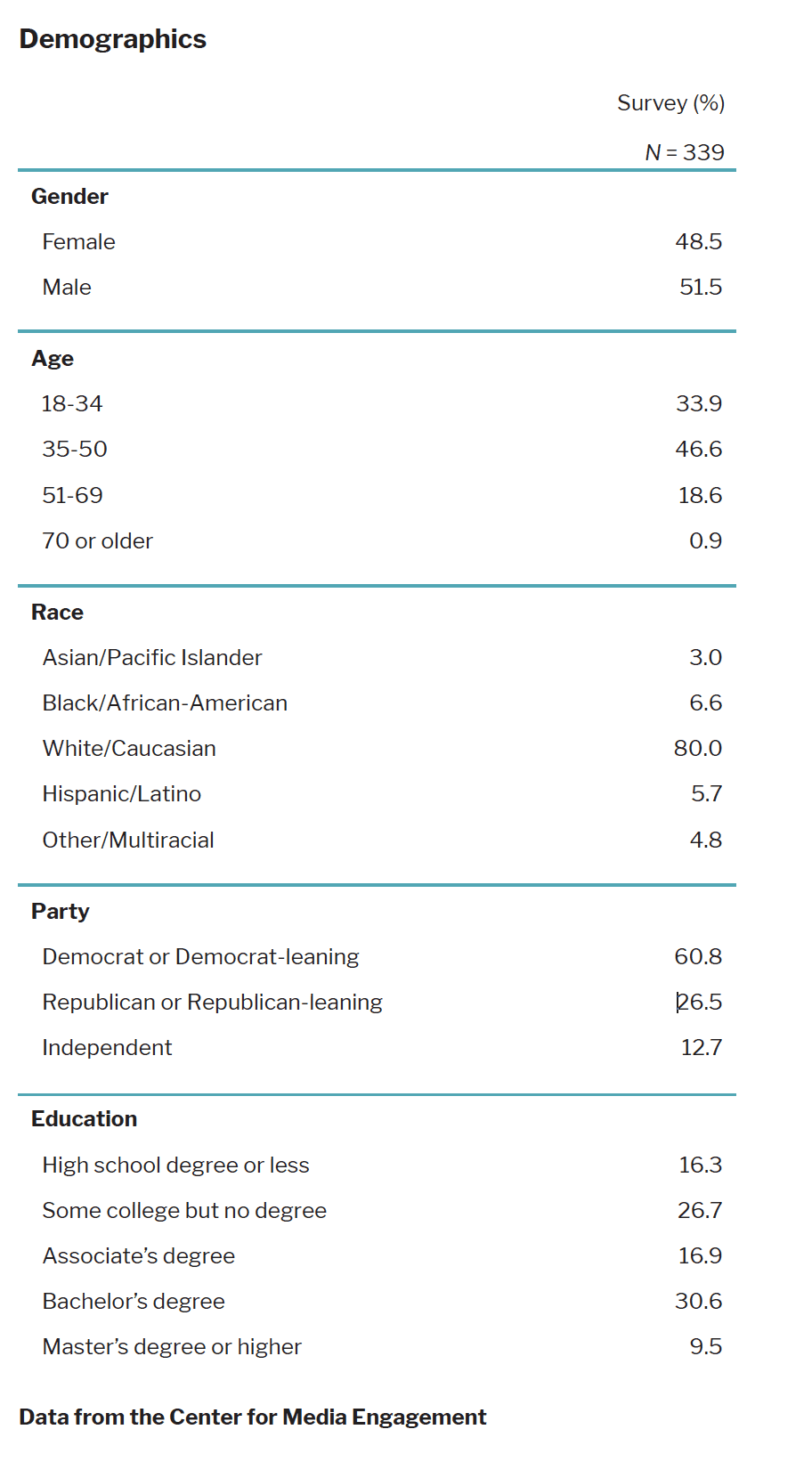

Responses were gathered between December 2021 and June 2022. In total, 324 participants were recruited from CloudResearch, a platform that draws respondents from Amazon’s Mechanical Turk, and 15 were recruited through outreach to organizations who serve those with substance use disorder, a disability, or issues with housing insecurity. In order to disguise the purpose of the study to gain participants who actually had these experiences, participants from CloudResearch were unaware of the criteria to participate in the study when they shared whether they had a physical disability, were in recovery from substance use disorder, or had been homeless.11

Participants were randomly assigned to read a news article about their group with stigmatizing terms (n = 169) or person-centered terms (n = 170). The news articles were adapted from real news articles from The Philadelphia Inquirer, Fast Company, and WWMT, a local news station in Michigan. The topics of articles were (1) how the end of a COVID-era plan for temporary housing in hotels affected people experiencing homelessness, (2) how the return to in-person offices impacted people with disabilities, and (3) how yoga can be a source of community and therapy for people in recovery.

We cleaned the data for straightliners (e.g., participants who selected the same answer for a series of contradictory statements), junk responses (e.g., gibberish in the open-ended responses), and duplicate respondents. We also removed respondents from the analysis who spent less than a third of the median time or more than three times the median time on the survey or the article.12

The final sample consisted of 90 people with a disability, 114 people who had experienced homelessness, and 135 people in recovery from substance use disorder. All participants were U.S. residents over the age of 18. More demographic information about the participants is available in the table below.

SUGGESTED CITATION:

Murray, C. and Stroud, N. J. (August, 2022). Person-centered terms encourage stigmatized groups’ trust in news. Center for Media Engagement. https://mediaengagement.org/research/person-centered-terms-encourage-stigmatized-groups-trust-in-news

- For reading on this topic, see these articles on person-first language in the news media, healthcare, and public discourse more broadly.[↩]

- Participants rated four statements about the trustworthiness of the article on a 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) scale. Responses to one statement were reverse coded so that higher values indicated higher levels of trust. Responses were averaged (M = 5.46, SD = 1.05, Cronbach’s alpha = .85). [↩]

- We tested for differences using ANOVA. There was a significant effect of condition F(1, 337) = 4.60, p = .03. There was not a significant interaction between condition and group F(2, 333) = 0.21, p > .05.[↩]

- Participants responded to five statements about their relationship with the journalist who wrote the article they read on a 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) scale. Responses were averaged (M = 5.15, SD = 1.22, Cronbach’s alpha = .89). [↩]

- We tested for differences using ANOVA. There was no significant effect of condition F(1, 337) = 1.00, p > .05 and no significant interaction between condition and group F(2, 333) = 1.88, p > .05.[↩]

- Participants rated their likelihood of participating in four actions related to news engagement on a 1 (very unlikely) to 7 (very likely) scale. Responses were averaged (M = 4.54, SD = 1.49, Cronbach’s alpha = .87). We tested for differences using ANOVA. There was no significant effect of condition F(1, 337) = 3.19, p > .05 and no significant interaction between condition and group F(2, 333) = 2.13, p > .05.[↩]

- Participants rated four statements about whether their group was respected in the news article on a 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) scale. Two statements were reverse coded so that higher values reflected more group esteem. Responses were averaged (M = 5.85, SD = 0.92, Cronbach’s alpha = .82). [↩]

- We tested for differences using ANOVA. A two-way ANOVA showed no significant interaction between group and condition F(2, 333) = 2.80, p > .05. Since the assumption of homogeneity of variance was not met for this variable, we used Welch’s adjusted F ratio, which showed a significant effect of condition F(1, 325.77) = 6.85, p < .05.[↩]

- Participants rated four statements about their representation in the news article on a 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) scale. Responses to one statement were reverse coded so that higher values reflected better representation. Responses were averaged (M = 5.46, SD = 1.03, Cronbach’s alpha = .82).[↩]

- We tested for differences using ANOVA. A two-way ANOVA showed no significant effect of condition F(1, 333) = 2.60, p > .05 and a significant interaction between group and condition F(2, 333) = 3.70, p = .03. Since the assumption of homogeneity of variance was not met for this variable and there were differences among groups, we used Welch’s adjusted F ratio to examine each group’s responses separately. Welch’s tests showed a significant effect of condition for people in recovery from substance use disorder F(1, 124.43) = 7.61, p < .05, but no effect for people who had experienced homelessness F(1, 109.60) = 2.61, p > .05 or people with a disability F(1, 87.24) = 2.26, p > .05.[↩]

- We inquired about the three experiences in a battery of nine other characteristics that were irrelevant to the study, such as “I would describe the area of the country I live in as rural,” “I have received welfare benefits” and “I have been employed as a journalist.” People who said all of the 12 possible characteristics applied to them were not allowed to proceed with the survey, and only those indicating that they had experienced the issues of interest in this study were able to proceed. [↩]

- Under this time criteria, 81 responses were excluded from the analysis. We performed the analysis using several different criteria for the minimum and maximum time spent with the survey and the article. The pattern of the results remained consistent across different criteria.[↩]