ABSTRACT

As the 2020 general election nears, voter’s phones will likely be buzzing with texts from political campaigns and groups. Campaigns have used this form of communication as an intimate way to communicate with voters since 2016 and use of this strategy has only increased as door-to-door outreach continues to be limited by COVID-19 and companies who specialize in Peer-to-Peer (P2P) texting attempt to capitalize on what may be the last national election cycle before regulations on these forms of communication are put in place.1 The advantages are obvious: texting is fast and easy and the open and response rates2 of these types of messages exceed alternatives such as email or mass broadcast texting.3 P2P texting provides a valuable opportunity to send private, personalized messages to voters that allow campaigns to build relationships with their constituents.

But hyper-personalized messages in private spaces, as well as lax regulations on these political texts, also create ideal opportunities for misuse. Political campaigns continue to develop ways to circumvent content moderation and regulations in their quest to gain votes and are able to sidestep state campaign disclosure and ad attribution laws. New forms of direct communication, such as through campaign apps and digital wallet passes on smartphones, are poised to bring political messaging to even higher levels of intimacy and efficacy, and, disturbingly, render them difficult to factually audit by outsiders.

INTRODUCTION

“Joe Biden endorsed giving 8 and 10 year olds sex change treatments. This is way too extreme for me. I can’t support him.” This message, claiming to come from an unnamed ‘Democratic volunteer’, began lighting up on people’s phones in swing states like Michigan, Wisconsin, and Pennsylvania the week before the 2020 election. The text message contained a short video paid for by the American Principles Project (APP). Phone calls to the phone numbers sending the messages fail, as they are now disconnected. APP paid Rumble Up, a conservative company offering texting services, over $58,000, as of October 2020.4

Screenshots of the message in question were reported by confused people on Twitter.5

Biden’s remarks on children’s transgender rights have been widely misrepresented online and have been at the center of many recent fact-checking investigations.6 APP, in fact, has been at the center of additional misinformation regarding trans-youth healthcare. Facebook refused to run their ad as a paid advertisement due to its misleading language.7 With social media platforms cracking down on misinformation and ramping up fact-checking, political actors are moving their efforts to more private, unregulated spaces such as text messaging to avoid such regulations.8 In this private realm of communication, content moderation is virtually nonexistent, allowing for the dissemination of false or misleading information, such as what was featured in these text messages from APP.

WHAT IS P2P TEXTING?

Through the use of messaging companies, campaign volunteers, or paid senders, P2P text messaging allows for the mass broadcasting of messages, with the added benefit of coming from an anonymous source, which appears to the receiver as an unknown long-form phone number. This process undermines the current assumption from the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) that “P2P messaging traffic typically covers low-volume exchange of wireless messaging among individual wireless consumers.”9 This definition becomes more and more outdated as political campaigns take advantage of the loophole by hiring texting companies like GetThru, Hustle, Opn Sesame, or RumbleUp that create a wrapper application for text messaging and allow a single person to send many auto-filled texts rapidly from a long-form phone number. Sometimes, smaller firms provide paid employees to mass-send messages, eliminating the need for volunteers and allowing campaigns to turn money into mass direct-to-voter messaging.10 P2P text messaging is particularly useful because it allows campaigns to have personalized, one-on-one conversations with voters in a quick and simple way. As phrased by a self-described expert in political P2P messaging:

Contact information for voters is collected from third-party data broker companies or through internal efforts.11 Organizations and campaigns often share information such as events, fundraisers, or polling locations, and, through P2P messaging, voters are in turn able to ask questions or share concerns directly with the campaign by simply responding to the text message. Campaigns can keep track of these responses and use information from the conversations to build more advanced profiles on individual voters.12 Using this information, campaigns can personalize messages and identify the most effective way to speak to voters.

The utilization of P2P texting as a communication tool for political campaigns is not a new phenomenon. In 2016, P2P was used heavily by campaigns who contracted with Hustle, a firm that provides the technological infrastructure to send mass P2P messages.13 By the 2018 midterms, P2P had experienced rapid growth, with over 350 million messages sent by Democratic campaigns and other political organizations in that year alone.14 In 2020, Republican and Democratic campaigns are heavily relying on SMS messaging as an important avenue for voter outreach and communication, even more so than before.15 President Trump’s re-election campaign alone planned to send “almost a billion texts” this year before Election Day.15 On the Democratic side, the Joe Biden campaign reports an increase in P2P texting engagement and has focused largely on training supporters and volunteers on how to engage in these P2P conversations with fellow supporters.16

Legal Loopholes Prompt Pseudo-Automation

Different from Broadcast (Application-to-Person) text messaging, which requires the user to opt into receiving messages from a short code number, P2P messaging functions under a different set of regulations.17 P2P messages are unsolicited, meaning that the receivers of these messages have not given permission to be contacted via text message. The FCC states, “political text messages can be sent without the intended recipient’s prior consent if the message’s sender does not use auto-dialing technology to send such texts and instead manually dials them.”18

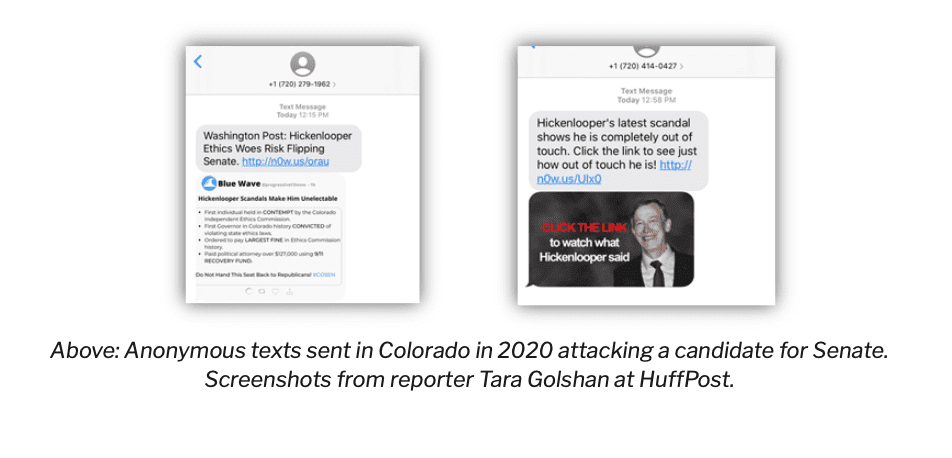

Capitalizing on this loophole, P2P texting uses forms of pseudo-automation to facilitate legal mass text campaigns. Technically not automated, these messages are sent by real people essentially pressing send over and over again. Campaigns can commission volunteers to send these scripted messages or they can hire companies to do it for them. By using subcontractors’ technology to send the messages, political actors are able to directly send content to people’s phones without appearing in Federal Election Commission (FEC) filings as paying to have sent the messages. Because of this, P2P text messages are able to work around state campaign finance laws and spread political messaging without attribution, such as was seen in Colorado earlier this year when voters received anonymous text messages spreading libel about democratic Senate Candidate John Hickenlooper.19

According to a 1983 opinion from the FEC elaborating disclosure rules for subcontractors, “payments to Consultants [may be reported] as expenditures without further itemization of payments made by Consultants to others.”20 For many P2P texts, the sender and number that appears on a voter’s phone fall under the category of “payments made by Consultants to others”. To outline this subcontracting process, a P2P texting “call center” like CampaignHQ21 which bills itself as “The Best Conservative Call Center in America,” may be paid directly and appear in FEC filings, but a subcontractor like Telephone Town Hall Meeting22 may be the one who actually sends the messages. These subcontractors are the traceable sender, and they have developed strategies to circumvent telephone companies’ self-imposed spam filters and conceal the firm that is being paid by politicians. This ties into a trend of undisclosed campaign spending in the U.S.23 For example, the P2P firm Opn Sesame, LLC appeared in the Campaign Legal Center‘s FEC complaint against the Trump campaign.24 Some of these subcontractors host in-house URL shorteners that allow clickthrough rates to be collected and, if a voter is linked to a campaign’s website, they may be surveilled by personally-identifying technology like tracking pixels and cookies.25 We have identified at least one misleading text messaging campaign that ultimately led to message recipients receiving an email with a tracking pixel. A prominent leader of one of these subcontractors described to us the value of an in-house URL shortener:

In another interview, the same expert who stressed the open rates of P2P messaging repeatedly stressed the importance of ‘best practices,’ using URL shorteners as an example: “The key thing with P2P texting and URL shorteners is that they are being flagged more and more as spam, especially in the first text, so a lot of best practices now tell folks to wait until the second text message to include a link.” When held under scrutiny, ‘best practices’ in P2P demonstrate an awareness within the P2P texting industry that this loophole, allowing for messages to legally be sent non-consensually as long as the process is not fully automated, is in danger of being closed if malicious texts gain enough attention. The same expert elaborated: “My biggest concern … is that people are not following best practices or not aware of best practices, and spamming people, and making it worse for people who have good intentions in using text … it could cause more regulations or restrictions by the carriers.”

P2P TEXTING: BROADCASTING DISINFORMATION

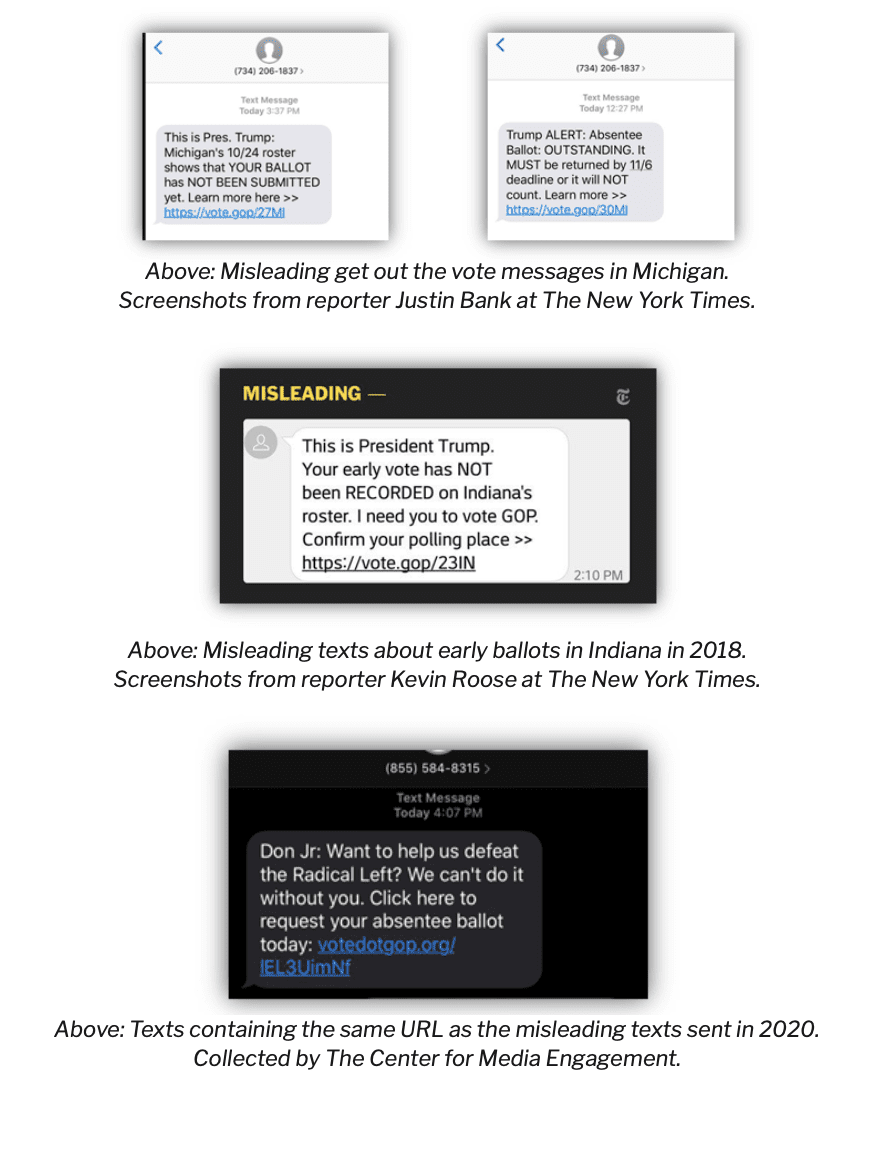

Despite the way that prominent P2P texting firms position themselves, not all messages are benign or are being successfully overlooked by the self-imposed spam filters and regulations that result from the give and take between the firms and telecarriers like Verizon.26 During the 2016 Presidential Election, fraudulent voter registration-related SMS messages, seemingly deployed by Republican campaigns, were sent to voters in several states. These messages provided misleading information about voter registration statuses. The New York Times collected screenshots of these messages, a few of which read, “This is Pres. Trump: Michigan’s 10/24 roster shows that your ballot has not been submitted yet. Learn more here.”27 Another read, “Trump Alert: Absentee ballot outstanding. It must be returned by 11/6 deadline or it will not count. Learn more.” Often, these messages contained information that was either inaccurate or misleading in relation to the receiver. Both texts attached a link to a website run by the Republican National Committee with a vote.gop domain, which can be purchased by anyone. Similar texts were received in several other states, such as Indiana and Kansas.28 These text messages sowed enough discord that the Monroe County Clerk’s Office in Michigan released a statement in an effort to correct the widespread confusion and urged voters to contact their clerk’s office if they encountered issues with absentee ballots.29 Further investigation revealed that the domain used in the messages is connected to Targeted Victory, a right-leaning digital strategy firm that formerly worked with Facebook.30

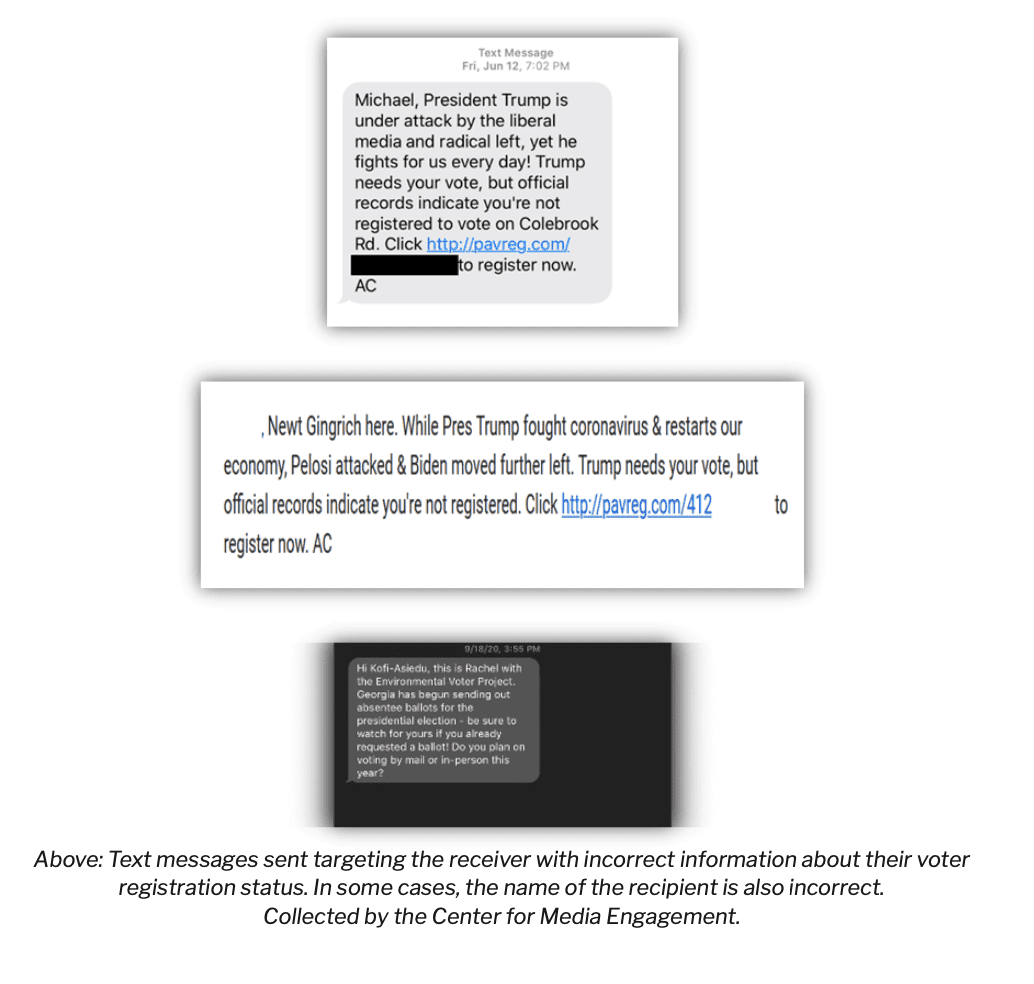

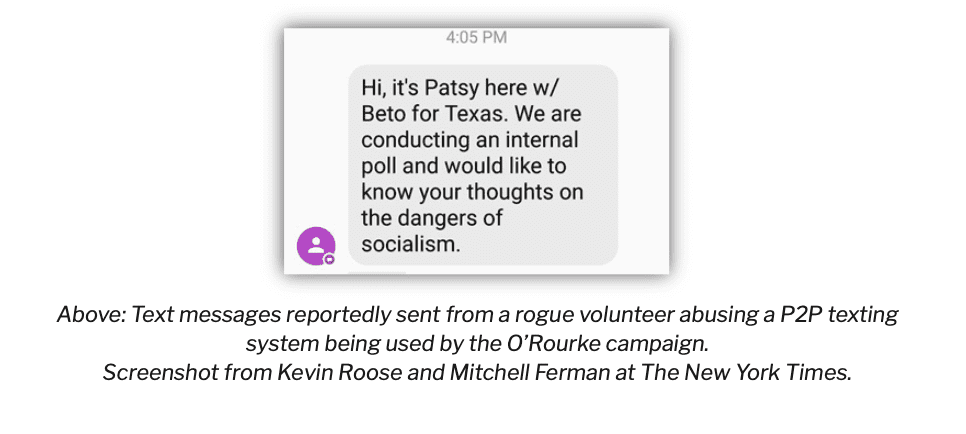

These voter suppression-like messages, and other disinformation-laden or misleading texts, are appearing again in 2020. We identified several text messages that warned voters of faulty voter registration statuses, including some from the same domain that prompted the Monroe County Clerk’s Office in Michigan to release a statement in 2016. Recent text messages tied to a company known as Advantage, Inc have often been mistargeted, for instance, addressing voters by the wrong name, which likely signals a sloppy data campaign.19 This mistargeting has caused confusion for many voters who received the messages. In another example of misleading P2P messaging, though reports of it have been rare, the current P2P infrastructure leaves some campaigns vulnerable to rogue volunteers who could edit the content of the messages they send.31

In addition to the FCC loophole concerning P2P versus Broadcast (Application-to-Person) texting, the FEC’s guidelines do not touch on MMS Multimedia Messaging Services. The regulations that do exist around SMS (Short Message Services) messaging are from 2002. SMS messages are limited to 160 characters per screen, with “characters” including letters, symbols, spaces, punctuation marks, and single digits. SMS texting falls under the same regulations as short-form messaging like political pins, bumper stickers, and skywriting, and is thus excluded from disclaimers.32 This framework does not consider the capabilities of MMS, which allows for content such as video (like the American Principles Project video outlined in the introduction), interactive surveys, and messages longer than 160 characters.33 Preparation and excitement for the past and future shift to MMS was expressed through multiple interviews with political consultants and digital strategists currently leveraging P2P messaging. When the anonymous subcontractors are combined with the lack of required disclosure, the result is mass political messaging sent from untraceable sources and received without consent in a space free from fact-checkers.

Given the loose regulations, the anonymity of the source, and the fact that P2P companies are making it more cost-effective to send MMS messages, which can include photos and videos, P2P messaging provides substantial opportunity for misuse. There are numerous examples that we collected in the course of our research that depict the ease with which P2P texting may be used to spread deceptive information. Additionally, as demonstrated in our interviews and in our lab’s own collection of text messages, phishing schemes previously seen predominantly in emails are beginning to appear in P2P texts, much to the chagrin of political consultants trying to keep regulators at bay. Below is a list of notable examples of mis- and disinformation spreading via P2P texts. Screenshots are sourced from the original reporting or from our own collection efforts:

Fake Bernie Sanders Campaign Text Refers To Elizabeth Warren As “Pocahontas”34

False Rumors Spread Via Text About Trump And Nationwide Quarantine35

False Texts In Kansas Spread Disinformation About COVID-19 Cases In The Area36

Misleading Texts From Trump About Successful Receipts Of Early Ballots37 Examples of Other Mis-targeted Get Out The Vote Text Messages

Examples of Other Mis-targeted Get Out The Vote Text Messages

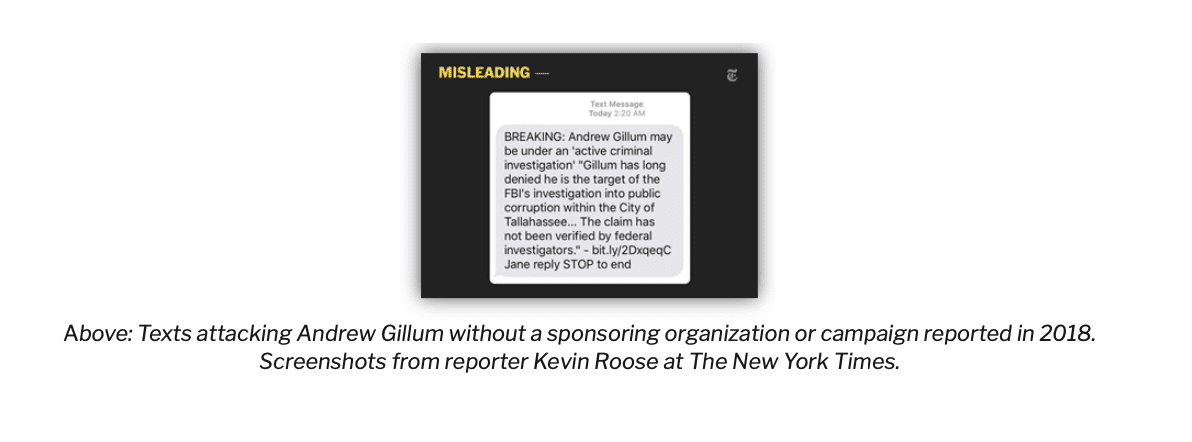

Fake and Unlabeled Texts Spread Lies about Andrew Gillum38

Fake and Unlabeled Texts Spread Lies about Andrew Gillum38

‘Impostor’ Sent Texts to Beto O’Rourke Supporters, Campaign Says39

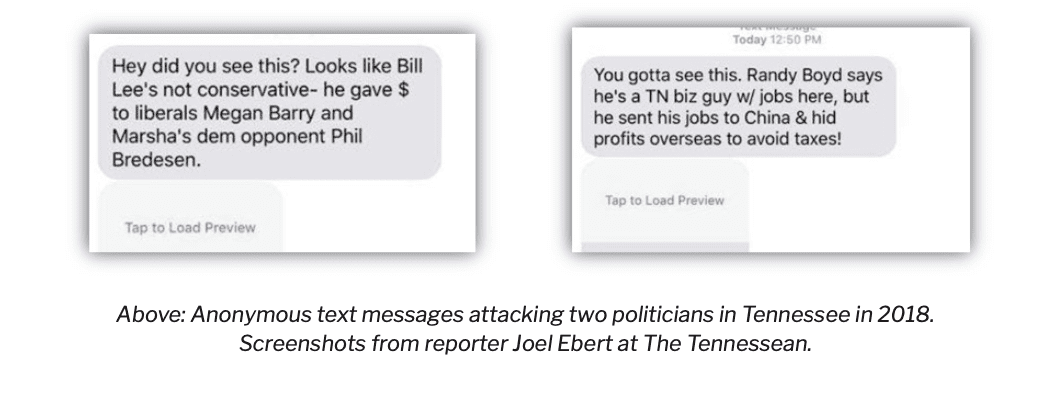

Fake Texts Smear Randy Boyd and Bill Lee in TN Election40

Fake Texts Smear Randy Boyd and Bill Lee in TN Election40

Anonymous Texts In Colorado Bashing John Hickenlooper41

Anonymous Texts In Colorado Bashing John Hickenlooper41

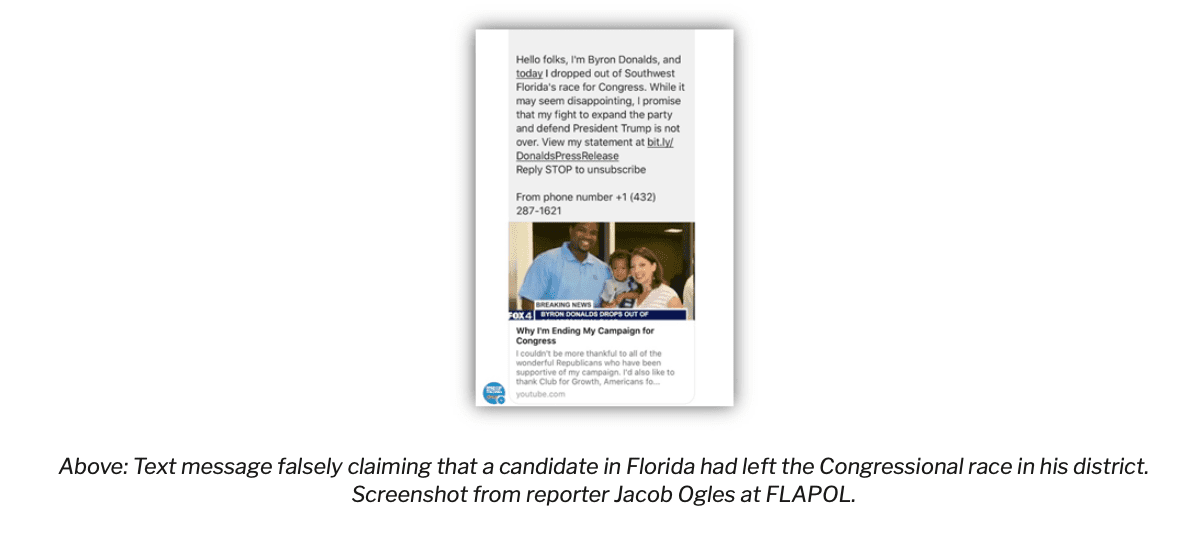

Fake Texts Spread In Florida About Byron Donald’s Dropping Out Of Election42

WALLET PASSES AND THE FUTURE OF P2P POST REGULATION

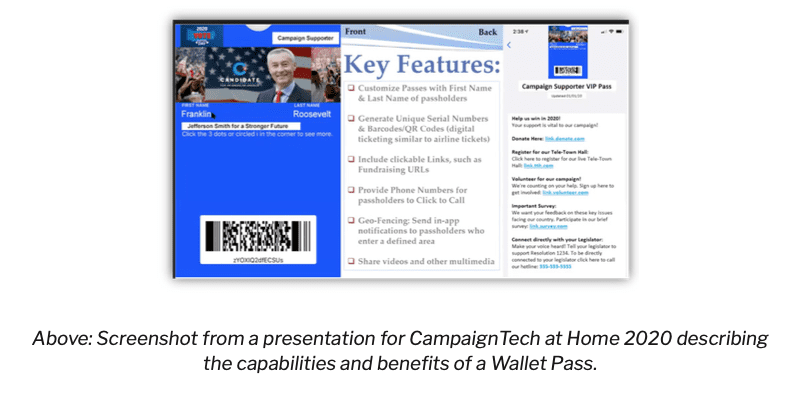

Preparing for incoming regulations on P2P texting, campaigns are beginning to access voters in a novel way—through the digital wallet app. Automatically installed on many smartphones, the digital wallet application is mostly used for storing credit/debit cards, boarding passes, movie tickets, coupons, or other items that are in need of easy access.43 Political campaigns are now using it to give voters easy access to their campaigns and, in turn, give the campaigns easy access to the voter. Several companies have created “a customized virtual supporter card for candidates than can be kept in voters’ wallets on their smartphones for an unlimited amount of time.”44 Users can add a campaign’s pass to their digital wallet through a customized link. Once a user clicks the link and adds the pass to their phone’s digital wallet app, they will have 24/7 access to the campaign—and the campaign will have access to them. Designed to be an alternative to a campaign app, which can be expensive to develop and difficult to convince people to download, a campaign pass serves as a “one-stop-shop for the most current information about a campaign” where voters can make donations, sign up for events, or take surveys, according to TeleTownHall’s Shaun Thompson, who spoke about this product at CampaignTech at Home.44 The content of these passes can also be edited in real-time by the campaign. Briefly touched on by Thompson in his presentation on July 17, 2020, the digital campaign wallet passes also have geo-fencing location tracking capabilities: “For voters who already have the Pass, [campaigns can] use geo-fencing to notify voters in advance of volunteers visiting their neighborhoods or events in their area.”45

These passes also allow a campaign to push unlimited notifications without needing a third-party texting service. Users simply download the pass and forget about it. In an interview with the CEO and founder of a prominent subcontractor for political P2P texting, “For example, if I would send Republicans a loyalty card, they will put it in their wallet and then I can invite them to Tucson for a rally … So if you put my ticket or pass into your wallet, I will be able to send you push notifications. The same as P2P texting, but it can be sent automatically, without volunteers or call centers.” Because these push notifications are not text messages, new regulations regarding SMS messaging will not affect them. These notifications also avoid the risk of getting flagged as spam and are not subject to carrier rate limits.46 Campaigns can also capitalize on the terms of service settings the user has already granted the wallet pass app, unlike a campaign app that requires a separate set of permission settings. Thompson explains:47 A provider of this service articulated that the intention is, in addition to providing Wallet Passes through avenues such as QR codes at campaign events, to use the current infrastructure of P2P texting to mass text Wallet Passes to users on behalf of clients before the loophole closes. One company offering Wallet Passes already offers to do this:48 “We send a Peer-to-Peer (P2P) Text to a targeted list of mobile phones inviting your members/ supporters to download the Wallet Pass for access to special benefits.”

A provider of this service articulated that the intention is, in addition to providing Wallet Passes through avenues such as QR codes at campaign events, to use the current infrastructure of P2P texting to mass text Wallet Passes to users on behalf of clients before the loophole closes. One company offering Wallet Passes already offers to do this:48 “We send a Peer-to-Peer (P2P) Text to a targeted list of mobile phones inviting your members/ supporters to download the Wallet Pass for access to special benefits.” In essence, the Wallet Pass is an attempt to pre-empt regulations and maintain a continuity of influence and direct access to people’s phones—replacing P2P texting with something functionally equivalent, on an equal scale, and just as open to abuse. Our team believes that regulations that aim to close the P2P texting loophole should also attempt to ensure that the current loophole is not used to exfiltrate targeted voters from P2P lists to Wallet Pass lists.

In essence, the Wallet Pass is an attempt to pre-empt regulations and maintain a continuity of influence and direct access to people’s phones—replacing P2P texting with something functionally equivalent, on an equal scale, and just as open to abuse. Our team believes that regulations that aim to close the P2P texting loophole should also attempt to ensure that the current loophole is not used to exfiltrate targeted voters from P2P lists to Wallet Pass lists.

Additionally, political campaign apps, like the Vote Joe app or Trump 2020 app, are on the rise in the United States. These apps provide politicians with a direct line to send messages to their supporters. For example, the Trump 2020 app has a news feed curated by the campaign and a hand-selected feed of pro-Trump tweets from various accounts. These apps, however, require a lot of time and engagement from supporters to download and use. The Wallet Pass will provide politicians which much cheaper and more accessible ways to build their own lines of news and messaging that go directly to individuals, opening up avenues for propaganda that are invisible to third-party fact-checkers.

THE POWER OF INTIMACY: P2P, RELATIONAL ORGANIZING, AND CAMPAIGN APPS

We have discussed P2P as an impersonal broadcasting tool, but it also is powerful when used to leverage preexisting relationships to send political messages from an intimate friend or relative.49 Defined as relational organizing, this concept of leveraging personal relationships to advance campaign agendas has long been used in political campaigning.50 In a guide to promote relational organizing digitally, Joe Biden defines the concept as, “when volunteers leverage their existing networks and relationships in support of our candidate … Friend-to-friend contact is one of the most effective methods for having meaningful conversations about our campaign, and it is an efficient way to persuade and identify supporters.” A strategy long used in campaigning, relational organizing is increasingly used in connection with digital tools, such as text messaging. Campaigns have built the designs of their apps around the knowledge that much of the contact we have with our friends is done via private messages. As an example, Joe Biden’s “Vote Joe” app calls on supporters to connect with their social circles via text message by accessing their lists of contacts and identifying potentially impressionable voters with whom the volunteers have a personal relationship.51 Users are provided with a script but encouraged to “tweak this language to reflect your relationship with the person and how you would typically talk to them. Press send and wait for a reply!”52

Campaign apps not only allow for a closed, unilateral messaging system from politicians to supporters, but they also leverage the loophole in P2P texting by auto-filling political messages out of the app into a users’ chosen messaging application. While this strategy of messaging takes longer to build to scale than mass P2P sent to purchased lists of phone numbers, political campaigns have begun the process of creating leverageable intimacy on a mass scale. The value of this was described to us by a prominent digital strategist known for staying ahead of the curve in the use of closed and intimate messaging:

Combining P2P texting and campaign apps allow for campaigns to identify supporters within their own networks and leverage their intimacy at scale and in a setting where fact-checking and outside validation is extremely hard to come by—leading to ubiquitous networks of personal influence that are invisible. Previously, having intimacy at scale was an oxymoron, but by combining campaign apps, relational organizing, and data-centric campaigning, volunteers are able to report their social networks directly to the campaigns. Volunteers are trained in sending P2P messages to their intimate networks in digital trainings or app trainings. These trainings are led by campaign members who teach volunteers best practices for navigating and operating the app.53 This quote from a recent app training demonstrates how to use the technology and how users can leverage their knowledge of personal networks to develop P2P text messaging as well as encourages reporting the information back to campaigns at scale:

The combination of relational organizing and personalized, private messages creates an impressively effective messaging strategy. “Not only does it allow you to reach a wider audience if your target audience is small,” a current expert in political text messaging shared, “but you can gain an air of legitimacy or credibility if you have a third party sharing your information and attaching your own credibility to the message that they share with their network. If you trust the person that’s sending it, you should trust the message.” In contrast to the use cases highlighted in the first half of this paper, where P2P messaging is used to send mass, anonymous messages from an unknown source, relational organizing and campaign apps use the same tool for hyper-personalized messages from a source who is very close to the receiver. They generate mass-scaled, highly-organized messaging from a source that is able to leverage an established rapport with the intended targets in ways that are poised to become increasingly invasive. As the process of combining large scale data analysis from campaigns with volunteers’ knowledge of their personal networks continues, personal contact lists become more and more effective. During training for the Vote Joe campaign app that researchers from our team attended, the relational manager demonstrated a hypothetical scenario in which a volunteer could leverage intimate knowledge of a friend’s health to benefit the campaign:

P2P text messaging in connection with relational organizing runs through a deeper thread in U.S. politics and technology’s role in political messaging and propaganda. The ability to collect and understand the social networks of supporters is something that digital political consultants lost in the past. As one prominent consultant explained to us:

The Open Graph API,54 and the doors it opened for combining personal data from sources like Facebook with a map of the social networks of millions of people, is what led to the Cambridge Analytica scandal, in which “Facebook’s default terms allowed their friends’ data to be collected by an app, unless they had changed their privacy settings.”55 The loophole in P2P messaging needs to be reevaluated if the sort of undue political influence of data analytics and social network analysis that has come to define the 2016 election cycle is to be avoided in the future.

CONCLUSION

P2P text messaging currently sits in a loophole that allows two opposite but parallel political uses. Its most prominent use is to send mass scale, anonymous messages that do not require campaign disclosure and to send to lists of cell phone numbers, a type of data that is becoming increasingly accessible because of the global shift to data-centric campaigning.26 The advent of the ‘campaign wallet pass’ is an attempt to maintain the power and scale of P2P messaging even after regulatory intervention comes into effect. We believe that, when regulations are put in place that encompass MMS and close the loophole for paid and unpaid volunteers to send consent-less messages that require no disclosure, there is additional consideration needed.

First of all, P2P messaging sent at mass scale with the help of specialized companies or through politician’s apps should require the same forms of opt-in consent as Application to Person messaging or mass emails. Second, political P2P messaging should have stricter campaign disclosure laws so that receivers are not left guessing who really sent them a message. Disclosure and consent should also apply to the messages sent through Wallet Passes. If the Wallet Pass and political push notifications are not also addressed, then messengers and companies who are taking advantage of the current loopholes will be able to use mass P2P texting to draw potential voters into downloading campaign wallet passes using networks built without consent or by using deceptive messages—such as a text lacking robust disclosure as to the true source of the Wallet Pass. This could become another potent vector for false information.

Without new regulations, voters will continue to receive these political texts throughout the election cycle. America is experiencing the 2020 ‘texting election,’56 where campaigns are systematically, but intimately, shifting their messaging to more private spaces than before. In the process, they’re leveraging personal networks. Loopholes in regulations, private spaces, and disinformation should catch the eye of regulators soon enough. And when they do, campaign apps and digital wallet apps are poised to offer politicians and political propagandists the versatility they need to stay ahead of regulations.

METHODOLOGY

This study is the result of a larger project examining propaganda on encrypted messaging applications conducted by the propaganda research team at the Center for Media Engagement at The University of Texas at Austin. In this project, we conducted 22 U.S.based interviews with political consultants and digital messaging experts over the course of 8 months. We also collected and analyzed instances in which P2P texting has been used to spread misleading or untrue information and categorized them based upon the nature of the information being spread.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Thank you to Martin Riedl and Joel Carter for their editorial help and Romi Geller and Jimena Pinzon for their diligent research. Gratitude to Paul Plevakas and Dr. Jolie Bookspan for their contribution and support. This report was funded by Omidyar Network, Open Society Foundations, and the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation.

SUGGESTED CITATION:

Glover, K., Gursky, J., Joseff, K., & Woolley, S. C. (2020, October 28). Peer-to-Peer texting and the 2020 U.S. election: Hidden messages and intimate politics. Center for Media Engagement. https://mediaengagement.org/research/peer-to-peer-texting-and-the-2020-election.

- Nagle, K. (2020, March 29). Politics: In a Time of Social Distancing, Person-to-Person Texting is Preserving Democracy: Sullivan. GoLocalProv. https://www.golocalprov.com/politics/in-a-time-of-social-distancing-person-to-person-texting-is-preserving- democ ; Shah, N. (2018, November 22). From Get-Out-To-Vote To Text-Out-To-Vote: The Rise Of Peer-To-Peer Texting. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2018/11/22/669591667/from-get-out-to-vote-to-text-out-to-vote-the-rise-of-peer-to-peer-texting. [↩]

- Open response rates of texts and emails refer to the percentage of receivers who open the message. Response rates of texts and emails refer to the percentage of receivers who respond to the message. From What is email open rate? Campaign Monitor. https:// www.campaignmonitor.com/resources/glossary/email-open-rate/. [↩]

- Why P2P Texting Over Mass Texting? (n.d.). RumbleUp. https://rumbleup.com/why-p2p-texting/. [↩]

- Expenditures by American Principles Project, 2020. OpenSecrets.org. https://www.opensecrets.org/outsidespending/expenditures.php?cmte=C00544387.[↩]

- PSU Blaze auf Twitter: “WTF is this? Just got this text an hour ago. What type of ‘Democratic volunteer’ would send this?…. https://t.co/ZZadMgKjm4.” (2020, October 25). Web.Archive.Org. https://web.archive.org/web/20201025222937/https://twitter. com/PSU_Blaze/status/1320470754803286018 ; MadDogPAC on Twitter: “This needs to be reported, and I don’t know wh…. (2020, October 27). Archive.Is. https://archive.is/mxfCg. [↩]

- Reuters Staff. (2020, October 22). Fact check: Fabricated Biden quote supports transgender children’s right to transition. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/article/uk-factcheck-biden-quote-transgender-chi/fact-check-fabricated-biden-quote-supports-trans- gender-childrens-right-to-transition-idUSKBN2772PM ; Swenson, A. (2020, October 21). Biden did not say transgender children should be able to ‘transition’. AP NEWS. https://apnews.com/article/fact-checking-afs:Content:9582957367fbclid=IwAR2zSey27tTUBRcb7vGWP6ZyXsGYfKpoiThD0XStKGs9sz6Q7ErIDrRJur4. [↩]

- Bauer, S. (2020, September 16). Facebook axes political ad saying trans athletes will ‘destroy girls sports’. NBCNews.com. https:// www.nbcnews.com/feature/nbc-out/facebook-axes-political-ad-saying-trans-athletes-will-destroy-girls-n1240262. [↩]

- Cowles, C. (2020, October 18). The Week in Business: Facebook Cracks Down. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/10/18/business/the-week-in-business-social-media-election-misinformation.html. [↩]

- (2018, November 21). Wireless Messaging Service Declaratory Ruling, WT Docket No. 08-7. https://docs.fcc.gov/public/attachments/DOC-355214A1.pdf [↩]

- Campaign Headquarters, The Best Conservative Call Center in America. Campaign Headquarters. https://www.campaign-head- quarters.com/. [↩]

- DeSilver, D. (2018, February 15). Q&A: The growing use of ‘voter files’ in studying the U.S. electorate. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/02/15/voter-files-study-qa/ ; Nickerson, D. W., & Rogers, T. (2014). Political campaigns and big data. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 28(2), 51-74. DOI: 10.1257/jep.28.2.51 [↩]

- Culliford, E. (2020, March 3). ‘Refused/Angry/Republican’: How 2020 text campaigns learn from voters’ replies. Reuters. https:// www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-election-texting/refused-angry-republican-how-2020-text-campaigns-learn-from-voters-replies- idUSKBN20Q1KI. [↩]

- Shah, N. (2018, November 22). From Get-Out-To-Vote To Text-Out-To-Vote: The Rise Of Peer-To-Peer Texting. NPR. https://www. npr.org/2018/11/22/669591667/from-get-out-to-vote-to-text-out-to-vote-the-rise-of-peer-to-peer-texting ; Hustle | Peer to Peer Texting Platform. (n.d.). Www.Hustle.Com. Retrieved October 26, 2020, from https://www.hustle.com/. [↩]

- Sullivan, M. (2020, March 4). Inside the 2020 campaign messaging war that’s pelting our phones with texts. Fast Company. https:// www.fastcompany.com/90469445/inside-the-2020-campaign-messaging-war-thats-pelting-our-phones-with-texts. [↩]

- Sullivan, M. (2020, March 4). Inside the 2020 campaign messaging war that’s pelting our phones with texts. Fast Company. https:// www.fastcompany.com/90469445/inside-the-2020-campaign-messaging-war-thats-pelting-our-phones-with-texts. [↩][↩]

- Trudo, H. (2020, April 1). Joe Biden’s ‘Text Team:’ Inside the Presumptive Nominee’s Shift to Digital. The Daily Beast. https://www. thedailybeast.com/joe-bidens-text-team-inside-the-presumptive-nominees-shift-to-digital ; Biden, J. (2020, October 21). VoteJoe Training. Vimeo. https://vimeo.com/458684381. [↩]

- What is P2P and APPLICATION-TO-PERSON messaging? (n.d.). https://support.twilio.com/hc/en-us/articles/223133807-What- is-P2P-and-A2P-messaging-. [↩]

- Rules for Political Campaign Calls and Texts. Federal Communications Commission. (2020, October 13). https://www.fcc.gov/ rules-political-campaign-calls-and-texts. [↩]

- Golshan, T. (2020, June 19). Coloradans Are Getting Mysterious Texts Bashing Democratic Senate Candidate John Hickenlooper. HuffPost. https://www.huffpost.com/entry/hickenlooper-colorado-senate-mystery-texts_n_5eecfe1ec5b6de061bd1458e. [↩][↩]

- Ifshin, D. (1983). CERTIFIED MAIL RETURN RECEIPT REQUESTED ADVISORY OPINION 1983-25. https://www.fec.gov/ files/legal/aos/1983-25/1983-25.pdf [↩]

- Campaign Headquarters, The Best Conservative Call Center in America. Campaign Headquarters. https://www.campaign-head- quarters.com/. [↩]

- Uniquely Interactive Mass-Communications by TTHM. TTHM. https://tthm.us/. [↩]

- Dark Money Process. OpenSecrets. https://www.opensecrets.org/dark-money/process. [↩]

- Christ, M. (2020, July 27). BEFORE THE FEDERAL ELECTION COMMISSION. Campaign Legal Center. https://campaignlegal. org/sites/default/files/2020-07/07-27-20%20Trump%20AMMC%20%28final%29.pdf ; Kim, S. R., & Will, S. (2020, July 28). Trump campaign accused of using “pass-through” vendors to obscure $170 million in payments. ABC News. https://abcnews.go.com/Poli- tics/trump-campaign-accused-pass-vendors-obscure-170-million/story?id=72020510 ; Peer to Peer Texting: Politics, Nonprofits, Commercial. Opn Sesame. https://opnsesame.com/. [↩]

- Hall, G. (2017, February -27). Cookies, Tags and Pixels– Tracking Customer Engagement. Nielson Marketing Effectiveness. https://resources.marketingeffectiveness.nielsen.com/blog/cookies-tags-pixels-tracking-customer-engagement. [↩]

- Krouse, S., & Glazer, E. (2020, October 27). Campaigns Clash With Cellphone Carriers Over Political Texts. The Wall Street Journal. https://www.wsj.com/articles/campaigns-clash-with-cellphone-carriers-over-political-texts-11603814631?mod=e2tw. [↩][↩]

- Bank, J. (2018, October 30). Election 2018 Misinformation Roundup: ‘Problematic’ Text Messages and Doctored Mailers. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/10/30/us/disinfo-text-messages-mailers.html. [↩]

- Associated Press. (2018, October 25). Kansas voters receive strange texts, purportedly from Trump. NBCNews.com. https://www. nbcnews.com/politics/elections/kansas-voters-receive-strange-texts-purportedly-trump-n924551 ; Roose, K. (2018, November 4). We Asked for Examples of Election Misinformation. You Delivered. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/11/04/ us/politics/election-misinformation-facebook.html. [↩]

- Taylor, C. (2018, October 19). Fraudulent texts on voter registration reported in Monroe County. The Monroe News. https:// www.monroenews.com/news/20181019/fraudulent-texts-on-voter-registration-reported-in-monroe-county. [↩]

- Hatmaker, T. (2018, November 30). Facebook quietly hired Republican strategy firm Targeted Victory. TechCrunch. https://tech- crunch.com/2018/11/30/facebook-targeted-victory-definers-gop/. [↩]

- Lapowsky, I. (2010, September 7). Fake Beto O’Rourke Texts Expose New Playground for Trolls. Wired. https://www.wired.com/ story/fake-beto-orourke-texts-expose-new-playground-for-trolls/. [↩]

- Sandstrom, K. J. (2002, August 23). ADVISORY OPINION 2002-09. https://www.fec.gov/files/legal/aos/2002-09/2002-09.pdf [↩]

- Eicher, R. Advances in MMS add interactive tools for mobile marketing. Mobile Marketer. https://www.mobilemarketer.com/ex/mobilemarketer/cms/opinion/columns/2440.html. [↩]

- Seitz, A. (2020, January 14). Text message wasn’t fabricated by Warren campaign. AP NEWS. https://apnews.com/article/8380009341. [↩]

- Robins-Early, N. (2020, March 17). Coronavirus Misinformation Is Spreading Through Bogus Texts And Group Chats. HuffPost. https://www.huffpost.com/entry/coronavirus-text-fake-misinformation_n_5e714e65c5b63c3b648682c5. [↩]

- KDHE warns Kansans of fake coronavirus texts. (2020, March 12). KWCH-12. https://www.kwch.com/content/news/KDHE-warns-of-Kansans-of-fake-coronavirus-texts-568746921.html?ref=921. [↩]

- Bank, J. (2018, October 30). Election 2018 Misinformation Roundup: ‘Problematic’ Text Messages and Doctored Mailers (Published 2018). The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/10/30/us/disinfo-text-messages-mailers.html ; Roose, K. (2018, November 4). We Asked for Examples of Election Misinformation. You Delivered. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes. com/2018/11/04/us/politics/election-misinformation-facebook.html.[↩]

- Roose, K. (2018, November 4). We Asked for Examples of Election Misinformation. You Delivered. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/11/04/us/politics/election-misinformation-facebook.html[↩]

- Roose, K., & Ferman, M. (2018, September 5). ‘Impostor’ Sent Texts to Beto O’Rourke Supporters, Campaign Says. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/09/05/us/politics/beto-orourke-texts-voting-texas.html.[↩]

- Ebert, J. (2018, July 13). Potentially illegal text messages attack Randy Boyd, Bill Lee as early voting begins. The Tennessean. https://www.tennessean.com/story/news/politics/tn-elections/2018/07/13/tn-governors-race-tennesseans-receive-potentially-illegal-text-messages-attacking-randy-boyd-billlee/783785002/.[↩]

- Golshan, T. (2020, June 19). Coloradans Are Getting Mysterious Texts Bashing Democratic Senate Candidate John Hickenloop- er. HuffPost. https://www.huffpost.com/entry/hickenlooper-colorado-senate-mystery-texts_n_5eecfe1ec5b6de061bd1458e.[↩]

- Ogles, J. (2020, August 18). Fake text says Byron Donalds dropped out of CD 19 race (he most certainly did not). Florida Politics. https://floridapolitics.com/archives/359419-fake-text-says-byron-donalds-dropped-out-of-cd-19-race-he-most-certainly-did- not.[↩]

- How to use Wallet on your iPhone, iPod touch, and Apple Watch. Apple Support. (2020, July 15). https://support.apple.com/en- us/HT204003 ; Wallet Passes | Passbook® Wallet for AndroidTM. (n.d.). Wallet Passes | Passbook® Wallet for AndroidTM. Retrieved October 22, 2020, from https://walletpasses.io/. [↩]

- Thompson, S. (2020, July). Phone-First Voter Contact P2P Text, Telephone Town Halls and In-App Notifications. CampaignTech at Home, online. [↩][↩]

- Thompson, S. (2020, July.) Phone-First Voter Contact P2P Text, Telephone Town Halls and In-App Notifications. CampaignTech at Home, online. [↩]

- Carrier rates are additional fees from mobile carriers for specific types of messages. From What are SMS and MMS Carrier Fees? Twilio Support. https://support.twilio.com/hc/en-us/articles/360016571913-What-are-SMS-and-MMS-Carrier-Fees-. [↩]

- Thompson, S. (2020, July) Phone-First Voter Contact P2P Text, Telephone Town Halls and In-App Notifications. CampaignTech at Home, online.[↩]

- App-Based Direct Connect. (n.d.). TTHM.US. https://tthm.us/tthm-toolbox/wallet-pass/. [↩]

- Han, H. (2014). How Organizations Develop Activists: Civic Associations and Leadership in the 21st Century. Oxford University Press ; McKenna, E., & Han, H. (2014). Groundbreakers: How Obama’s 2.2 Million Volunteers Transformed Campaigning in America. Oxford University Press ; Bond, R. M., Fariss, C. J., Jones, J. J., Kramer, A. D., Marlow, C., Settle, J. E., & Fowler, J. H. (2012). A 61-million-person experiment in social influence and political mobilization. Nature, 489(7415), 295-298 ; Green, D. P., and Gerber, A.S (2004). Get out the Vote! How to Increase Voter Turnout. Brookings Institution Press; Warren, M. R. (2001). Dry Bones Rattling: Community Building to Revitalize American Democracy. Princeton University Press. [↩]

- Bond, R. M., Fariss, C. J., Jones, J. J., Kramer, A. D., Marlow, C., Settle, J. E., & Fowler, J. H. (2012). A 61-million-person experiment in social influence and political mobilization. Nature, 489(7415), 295-298 ; Heaney, M.T., and Rojas, F. (2007). Partisans, Nonpartisans, and the Antiwar Movement in the United States. American Politics Research 35(4),431–64. https://doi. org/10.1177/1532673X07300763. [↩]

- Biden, J. (2020, October 21). VoteJoe Training. Vimeo. https://vimeo.com/458684381. [↩]

- Team Joe App iOS Guide Why is Relational Organizing Important? (n.d.). In Team Joe App iOS Guide – Joe Biden for President. https://go.joebiden.com/page/-/Team%20Joe%20App%20Guide%20%282%29.pdf [↩]

- Biden, J. (2020, October 21). VoteJoe Training. Vimeo. https://vimeo.com/458684381. [↩]

- Albright, J. (2018, March 21). The Graph API: Key Points in the Facebook and Cambridge Analytica Debacle. The Tow Center for Digital Journalism on Medium. https://medium.com/tow-center/the-graph-api-key-points-in-the-facebook-and-cambridge-ana- lytica-debacle-b69fe692d747 [↩]

- Cadwalladr, C., & Graham-Harrison, E. (2018, March 17). How Cambridge Analytica turned Facebook ‘likes’ into a lucrative political tool. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2018/mar/17/facebook-cambridge-analytica-kogan-data-algorithm?CMP=twt_a-media_b-gdnmedia. [↩]

- Zarroli, J. (2020, October 7). Getting Lots Of Political Messages On Your Phone? Welcome To “The Texting Election.” NPR. https:// www.npr.org/2020/10/07/920776670/getting-lots-of-political-messages-on-your-phone-welcome-to-the-texting-election. [↩]