Summary

The Center for Media Engagement partnered with a local television news station to examine what happens when journalists take a more active role in the comments on the station’s Facebook page.

Our results demonstrate that a reporter interacting with commenters can improve the civility of the comments. The same was not true of an unidentified staff member using the station’s logo as their profile picture interacting with commenters. We suggest that newsrooms have a reporter interact in the comment section in ways that spark conversation and highlight productive comments. For example:

- Answer legitimate questions from commenters (e.g., “Good question, Mandy…”)

- Ask questions of commenters (e.g., “What are your thoughts on that?”)

- Provide additional information (e.g., “Here’s a link to the bill text.”)

- Encourage and highlight good discussion (e.g., “Tom, you bring up something interesting.”)

The Problem

Incivility can run rampant in online comment sections. From a democratic angle, incivility on news sites creates reasons for concern. Social science research finds that incivility in the news depresses trust in government institutions.1 Even more, incivility in comment sections can affect readers’ beliefs and even change what people think about the news itself. 2

From a business angle, some journalists worry that incivility-laced comment sections can damage their reputation and can harm the overall news brand.3 Although news organizations can employ moderators to remove uncivil comments from these online forums, the practice can be both time-consuming and expensive.

Some newsrooms are hesitant to have journalists get involved in online comment sections, believing that such engagement could be a distraction from the primary job of reporting the news. Other newsrooms see the comment section as a place to learn from and engage with the news audience, as well as build loyalty to the news outlet. Our study seeks to uncover whether newsroom engagement in the comment section has benefits.

With this in mind, we conducted a field study with a media partner to examine what happens when journalists take a more active role in comment sections. We looked at what happens when newsroom staff engages in comment sections – does having a reporter or a staff member from the newsroom change the substance of the comments?

Key Findings

To reduce uncivil comments, have a reporter interact in the comment section in ways that spark conversation and highlight productive comments. For example:

- Answer legitimate questions from commenters (e.g., “Good question, Mandy…”)

- Ask questions of commenters (e.g., “What are your thoughts on that?”)

- Provide additional information (e.g., “Here’s a link to the bill text.”)

- Encourage and highlight good discussion (e.g., “Tom, you bring up something interesting.”)

Implications for Newsrooms

Optimistically, online comment sections offer a forum for gathering and sharing diverse opinions. Newsrooms have much to gain from these spaces – a loyal online community, feedback on the news, and a reason for visitors to come back and spend more time on the site. But the potential downsides are daunting.

News comment sections – while hopeful representations of what democratic participation online could be – can turn into uncivil hotbeds of distortion, attack, and vulgarity.4 Uncivil comment sections can change impressions of the news and may hurt the news brand. How can news organizations foster the benefits of comment sections and limit the downsides? Our research offers a practical suggestion. Reporters can get involved in the comment section, engaging politely with site visitors. Although this task may seem too time-consuming, the reporter and station in our study did not expend extraordinary efforts– the reporter interacted, on average, just over four times a day. This practice reduced, but did not cure, incivility in Facebook comments.

The Study

In our study, we partnered with a local television news station with a vibrant Facebook community. The station was an affiliate of a major television network in a top-50 Designated Market Area (DMA). Over 40,000 people had liked the station’s Facebook page at the time of the study.

The study took place between December 2012 and April 2013.5 For each day of the study, the station posted a political story on Facebook and then varied their interactions with commenters according to a randomized schedule.6

One of three things happened on each of the 70 days of the study:

- Reporter Interaction: The station’s well-known political reporter would comment and respond to commenters.

- Station Interaction: The station’s web team, using the station’s logo as their identity, would interact in the comment section.

- No Interaction: No one from the station would interact in the comment section.

We gave the reporter and the station several tips for interacting on the site:7

- Responding to questions. For example, the reporter posted the following when a commenter asked a question of her fellow commenters: “Good question, Mandy. That would seem to me where legal clashes could happen. I believe the Nebraska bill does include exceptions for the life of the mother.”8

- Asking questions. Some of the interactions involved asking questions related to the post topic, such as: “We hear from both parties about the issue of undocumented immigrants being freed from federal custody. What are your thoughts on that?”

- Providing additional information. When the reporter or station had more information to offer, they were encouraged to add these additional insights to the discussion. For example, the reporter shared this comment and a hyperlink in a discussion related to regulating medical marijuana: “FYI, here’s the text of the bill filed by State Rep. Smith. Just in case you’d enjoy some light reading: [LINK]”

- Encouraging and highlighting good discussion. The reporter and station recognized commenters who were adding to the depth and breadth of the online conversation. In the following example, the reporter acknowledged the contribution of a commenter and then used his comment to ask a question: “Tom, you bring up something interesting: This issue is often seen as ‘Democrats vs. Republicans’ as much as it is seen as ‘Pro-Choice vs. Pro-Life.’ I’m curious, do any of you consider yourselves pro-choice Republicans or pro-life Democrats?”

Research Findings:

- No effects on number of comments. The number of comments was unrelated to whether the station or reporter interacted in the comment section.9

- Reduced incivility with reporter interaction. When the reporter interacted in the comment section, incivility declined. As shown in the figure below, the chances of an uncivil comment declined by 17 percent when a reporter interacted in the comment section compared to when no one interacted. When the station interacted, it had no effect on the incivility of comments.10

Three explanations may account for the reporter interaction reducing incivility, but not the station. First, the reporter commented more per post than did the station. For posts where the station interacted with commenters, the station had an average of 1.13 comments. On average, the reporter wrote 4.48 comments on posts where he was tasked with interacting. Higher rates of commenting may explain why the reporter, and not the station, reduced incivility.

Second, the station had, from time to time, commented in the past. The novelty of the reporter interacting may account for the results.

Third, it is possible that seeing a recognizable reporter from the news broadcast – as opposed to a generic station logo accompanying each comment – sparked additional civility. This study cannot sort out whether one, two, or all three, of these explanations account for the effects. What is clear, however, is that having a reporter engage in the comment section can affect the civility of the comments.

Method

We looked at all 2,408 comments that were left on the site in response to the 70 station posts and recorded the number of comments generated by each post. After monitoring the site, we noticed that commenting generally subsided within a day or two after the post was published. Thus, we archived comments three days after publication. On average, posts received 33 comments.

To evaluate whether each comment was uncivil, we looked for a series of different characteristics.11 To be coded as uncivil, the post needed to include one or more of the following attributes:

- Obscene language / vulgarity

- Insulting language / name calling

- Ideologically extreme language (e.g.,“Sure, Jeffrey, that’s what it was. It couldn’t possibly be that the majority of voters saw through the GOP’s distortions and their desire to only help the rich get richer. Oh, and let’s not forget their plan to kick women back to the 1950’s.”)

- Stereotyping (e.g., “I just don’t want them to smoke & drive. Like drunks do. Let’s make streets safer not worse.”)

- Exaggerated argument (e.g., “HAH! They’ll never do it! These A@$#*les make wayyy too much moola off the public for this stuff.”)

Any comment that contained any of these characteristics was coded as uncivil. Across all of the comments, we coded 47% as uncivil.

Additional Attributes

In addition to the attributes previously mentioned, we also coded for several other attributes of the posts and comments which were controlled in our analysis.

Post Attributes

- Topic. Posts discussed crime / guns (26%), economy (26%), education (30%), and health (23%). Posts could be coded for multiple categories; for example, a post about how state budget cuts might affect education would fall under economy and education.

- Conversation Starter. We recorded whether each post included a closed-ended question (26%), an open-ended question (44%), or a discussion starter where commenters were prompted to participate without a question (e.g., “Leave your comments below”; 31%). Thirty-one percent of posts did not include an open-ended question, a closed-ended question, or a discussion starter.

Comment Attributes

- Reporter / Station Comment. We recorded whether the comment made was by the reporter, the station, or an audience member. Only 5 percent of posts were from the station or reporter. These were removed from our analyses.

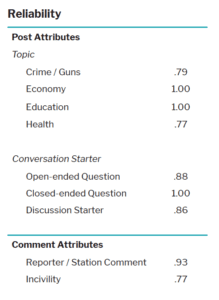

Reliability

We went through several rounds of coding to establish reliability. In this process, multiple people coded the same post or comment, and their responses were compared to see if they reached the same conclusion about the content. For example, we measure whether multiple people identified (or did not identify) incivility in a comment when following the rules we established for identifying incivility. To measure reliability, we used Krippendorff’s alpha. Values of Krippendorff’s alpha closer to 1.00 indicate more reliable coding, with values in excess of .80 considered particularly strong and values in excess of .67 considered acceptable.

SUGGESTED CITATION:

Stroud, Natalie Jomini, Joshua M. Scacco, Ashley Muddiman, and Alex Curry. (2014, September). Journalist Involvement in Comment Sections. Center for Media Engagement. https://mediaengagement.org/research/journalist-involvement/

- Mutz, D. C., & Reeves, B. (2005). The new videomalaise: Effects of televised incivility on political trust. American Political Science Review, 99, 1-15. [↩]

- Brossard, D., & Scheufele, D. (2013, March 2). This story stinks. New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2013/03/03/opinion/sunday/this-story-stinks.html?_r=0; Anderson, A. A., Brossard, D., Scheufele, D. A., Xenos, M. A., & Ladwig, P. (forthcoming). The “nasty effect:” Online incivility and risk perceptions of emerging technologies. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication. [↩]

- Singer, J. B., & Ashman, I. (2009). “Comment is free, but facts are sacred:” User-generated content and ethical constructs at the Guardian. Journal of Mass Media Ethics, 24, 3-21. See also Hermida, A., & Thurman, N. (2008). A clash of cultures: The integration of user-generated content within professional journalistic frameworks at British newspaper websites. Journalism Practice, 2, 343-356. [↩]

- Diakopoulos, N., & Naaman, M. (2011, March). Towards quality discourse in online news comments. In Proceedings of the ACM 2011 conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work (pp. 133-142). ACM. [↩]

- Note that we did not conduct the study on weekends, holidays, or days when there was breaking news that prevented the station from taking part. [↩]

- This study is appropriately understood as a quasi-experiment. Although we randomly assigned the type of interaction (e.g., whether the station interacted, a reporter interacted, or neither), other factors, such as the topic of the post, were not under our control. Further, we did not randomly assign the conversation starter (e.g., open or closed-ended question). For this reason, we control for post topic, retaining education and health in our final model as these were the only two significant topical predictors. We also control for mentions of partisanship / ideology in the comments, a variable unrelated to who interacted or the presence / absence of any conversation starters, but significantly related to incivility. [↩]

- As we discuss later, the reporter interacted more and used these techniques more frequently than the station. [↩]

- Example comments have been slightly altered, and names have been changed, to protect the identity of the commenters. [↩]

- As the dependent variable (number of comments) was measured at the post-level, rather than the comment-level, ANOVA was used. An ANOVA predicting the number of comments revealed no significant effect of interaction (F(2,64)=.57, p=.57). Note that we removed all comments made by the reporter or the station from the analysis as the presence of these comments could inflate artificially the number of comments. [↩]

- We used a logistic regression analysis predicting incivility, controlling for topic and conversation prompt. The reporter reduced incivility (B = -0.70, SE = 0.32, p < .05), whereas the station had no effect (B = 0.10, SE = 0.20, n.s.). [↩]

- Papacharissi, Z. (2004). Democracy online: Civility, politeness, and the democratic potential of online political discussion groups. New Media & Society, 6(2), 259–283. doi: 10.1177/1461444804041444; Sobieraj, S., & Berry, J. M. (2011). From incivility to outrage: Political discourse in blogs, talk radio, and cable news. Political Communication, 28(1), 19–41. doi: 10.1080/10584609.2010.542360 [↩]