SUMMARY

The Center for Media Engagement tested journalist responses to Facebook comments on news stories in order to find out which responses led to more positive perceptions regarding the news outlets and its comment moderation. The messages were tested in the U.S. and Germany to see how well they worked across different cultures. We found that:

- In both countries, responses that acknowledged – rather than dismissed – a commenter’s emotions led to more positive attitudes toward the news outlet and its handling of the comment thread.

- These findings were true regardless of the topic of the discussion.

The results suggest that journalists should try to acknowledge a commenter’s emotions when engaging in comment threads and should avoid dismissing the commenter’s emotions, even when trying to redirect their behavior to be civil.

THE PROBLEM

Center for Media Engagement (CME) research shows comment threads have more productive discussions when journalists engage1 in them. Even though journalists are often expected to engage, another CME report suggests they often receive little training about what to say.2

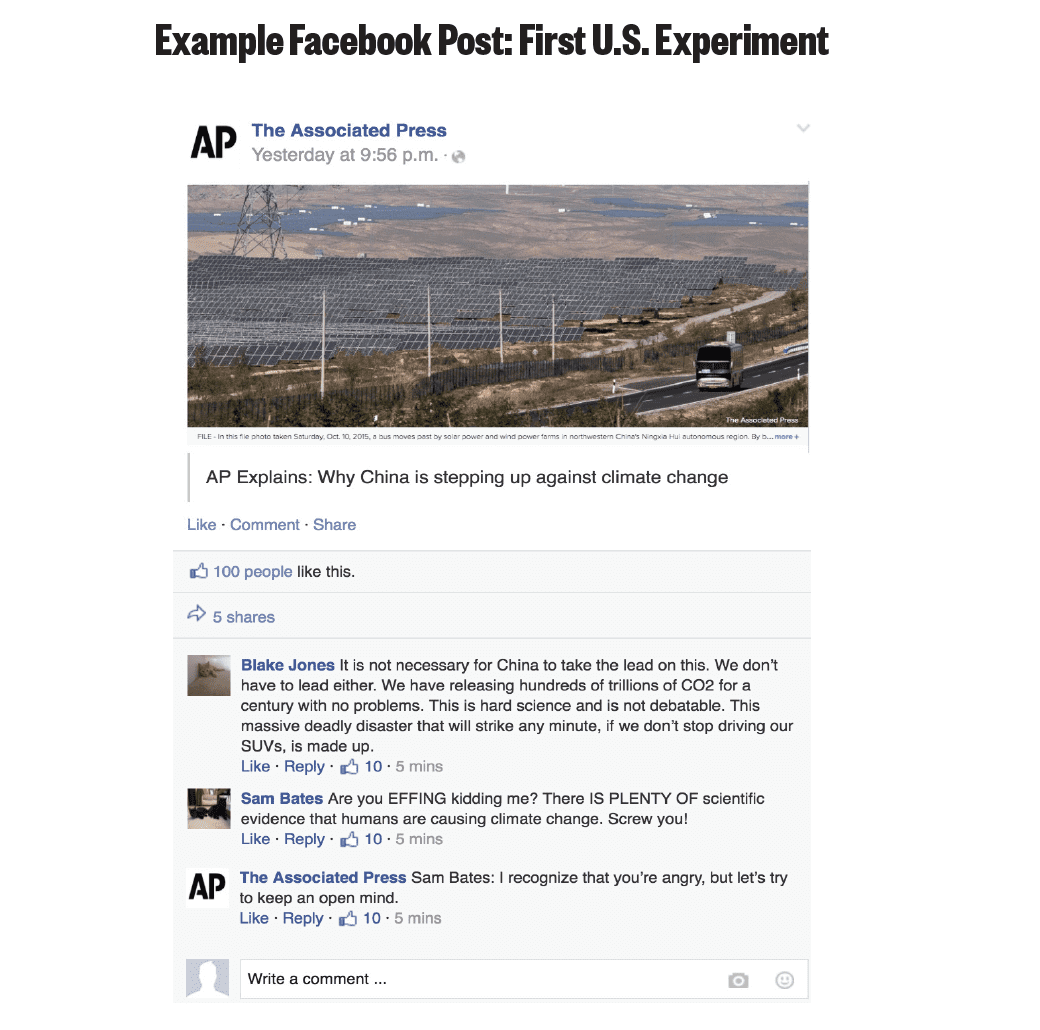

This study examined what messages journalists should use to respond to commenters on their news organizations’ social media pages, especially when trying to encourage civility. We tested two types of messages: one that acknowledged a commenter’s emotions – “I recognize that you’re angry, but let’s try to keep an open mind” – and one that dismissed the commenter’s emotions – “Don’t get bent out of shape.”3

We tested these messages in both the United States and Germany in order to see how well they worked in different cultures. Experiment 1 was funded by The Vice President for Research at The University of Texas at Austin. Support for the U.S. portion of Experiment 2 came from the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation. Support for the German portion of Experiment 2 came from the Center for Media Convergence at the Johannes Gutenberg University of Mainz, Germany.

KEY FINDINGS

- In both countries, responses that acknowledged – rather than dismissed – a commenter’s emotions led to more positive attitudes toward the news outlet and its handling of the comment thread.

- In the U.S., this result held up regardless of whether the discussion was impolite (containing swear words), uncivil (containing stereotypes or threats to democracy),4 or civil (making rational points). In Germany, civil discussions led to significantly more positive attitudes toward the news outlet, compared to impolite discussions, regardless of what message was used to respond to those comments.

- In both countries, these findings were true regardless of the topic of the discussion or whether the person making the response was a journalist or another commenter.

IMPLICATIONS

- Journalists should try to acknowledge commenters’ emotions when they engage in comment threads.

- Journalists should avoid dismissing commenters’ emotions, even when they are trying to redirect their behavior to be civil.

- This approach was largely effective for civil, uncivil, and impolite comments. But we do not advocate that it be used when responding to more virulent comments, such as hate speech or abuse. In those cases, engagement is too risky, and the comments should be removed.

FULL FINDINGS

For the first experiment, we created mock discussions on what appeared to be a Facebook page5 for The Associated Press. The discussion consisted of three comments on a news post. The first comment civilly discussed the news post. The second comment impolitely criticized the first commenter. The third comment was from a journalist attempting to diffuse the second commenter’s emotions. There were two types of journalist comments: one that acknowledged and one that dismissed the second commenter’s emotions.

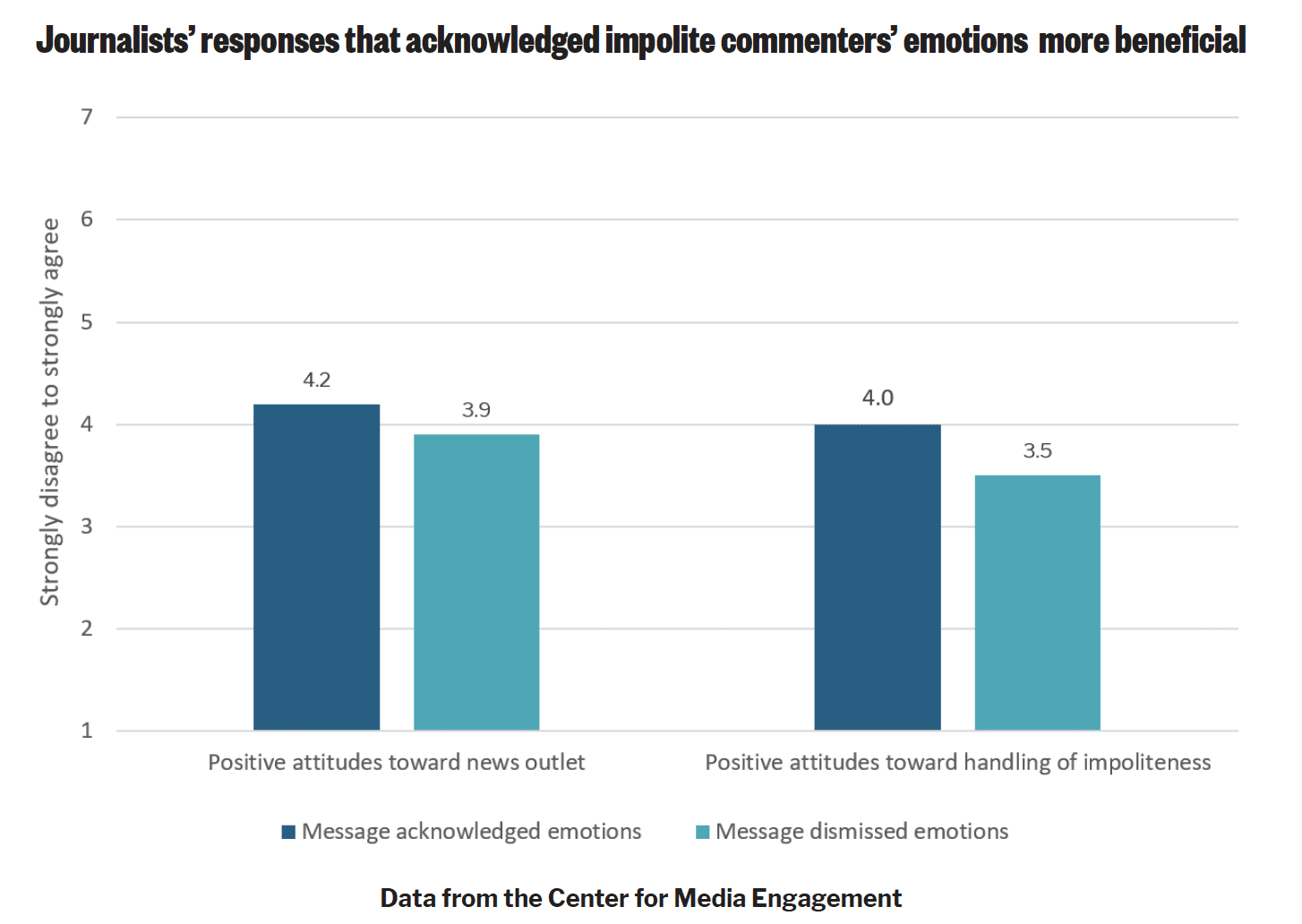

This experiment was conducted only in the United States. Participants had significantly more positive perceptions of the news outlet if they were exposed to a Facebook post with a journalist’s response that acknowledged the impolite commenter’s emotions – rather than a journalist’s message that dismissed the impolite commenter’s emotions. This was true for both outcomes we examined: positive attitudes toward the news outlet and positive attitudes toward the news outlet’s handling of the impoliteness.6 We examined these messages regarding two controversial news topics, climate change and immigration. Across both topics, participants perceived the response that acknowledged the commenter’s emotions as more beneficial.

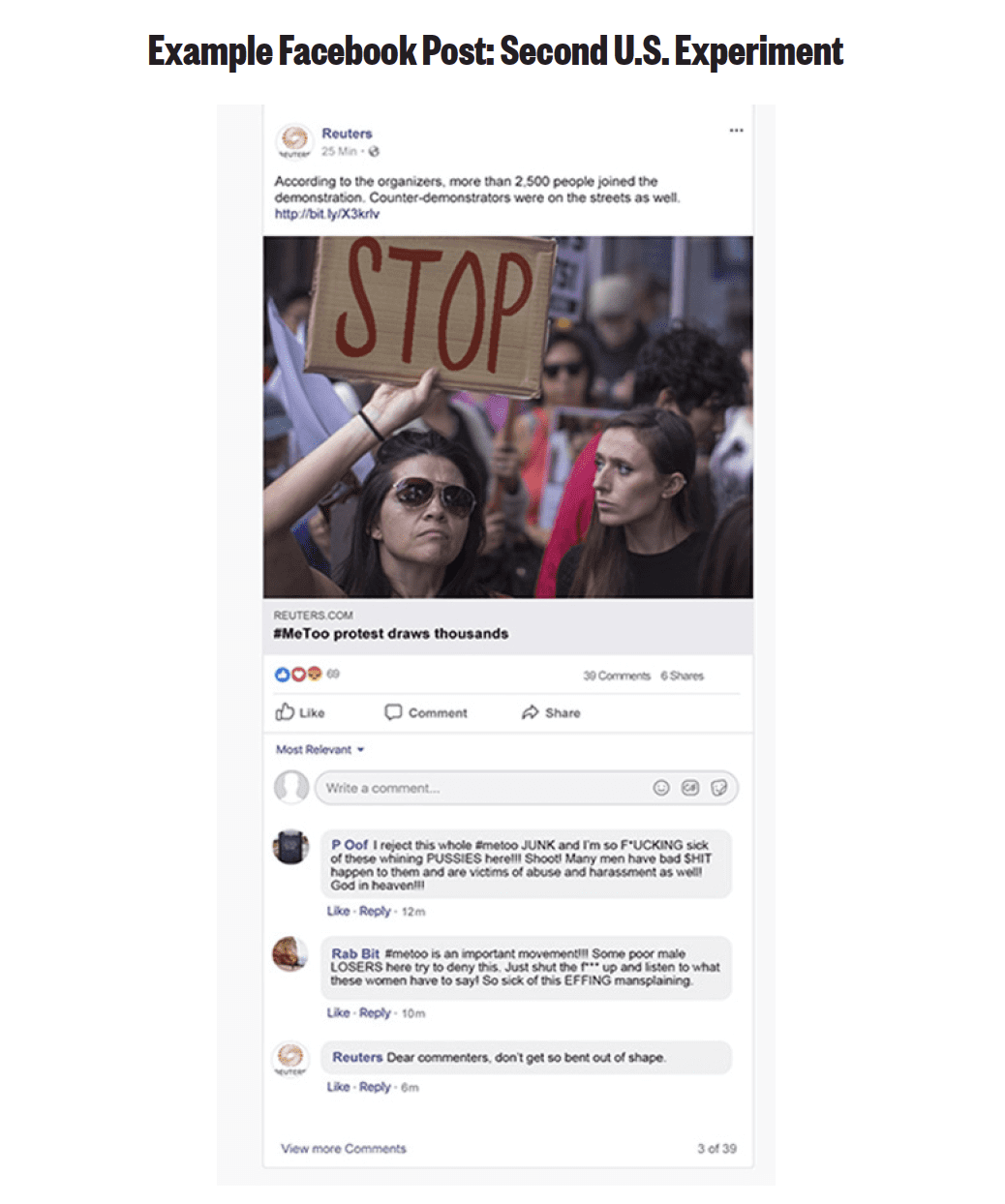

The second experiment was conducted in both the U.S. and Germany in a similar manner as Experiment 1, but Reuters was used as the new outlet because it has a more global reach than The Associated Press. Participants saw a mock Facebook post with a photograph, headlines, and three comments.

In this experiment, we wanted to see if the tone of the initial two comments – whether they were uncivil, impolite, or civil – changed the results. We also wanted to see if it mattered whether a journalist, another commenter, or no one responded to the initial two comments. As a result, participants were randomly assigned to see two initial comments that were either uncivil, impolite, or civil. They also were randomly assigned to see a either a third comment that acknowledged the commenters’ emotions, a third comment that dismissed the commenters’ emotions, or no third comment in the control condition.

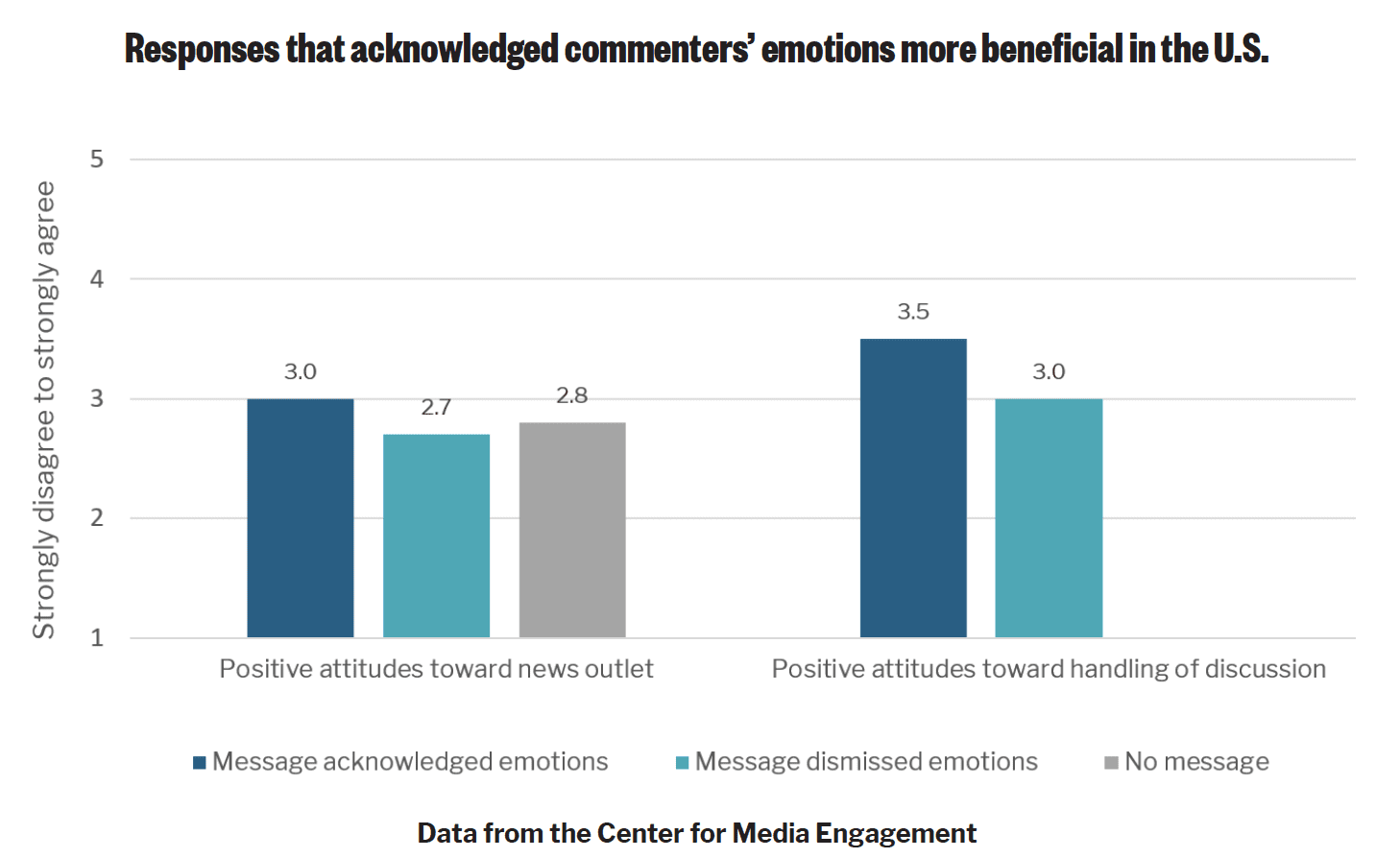

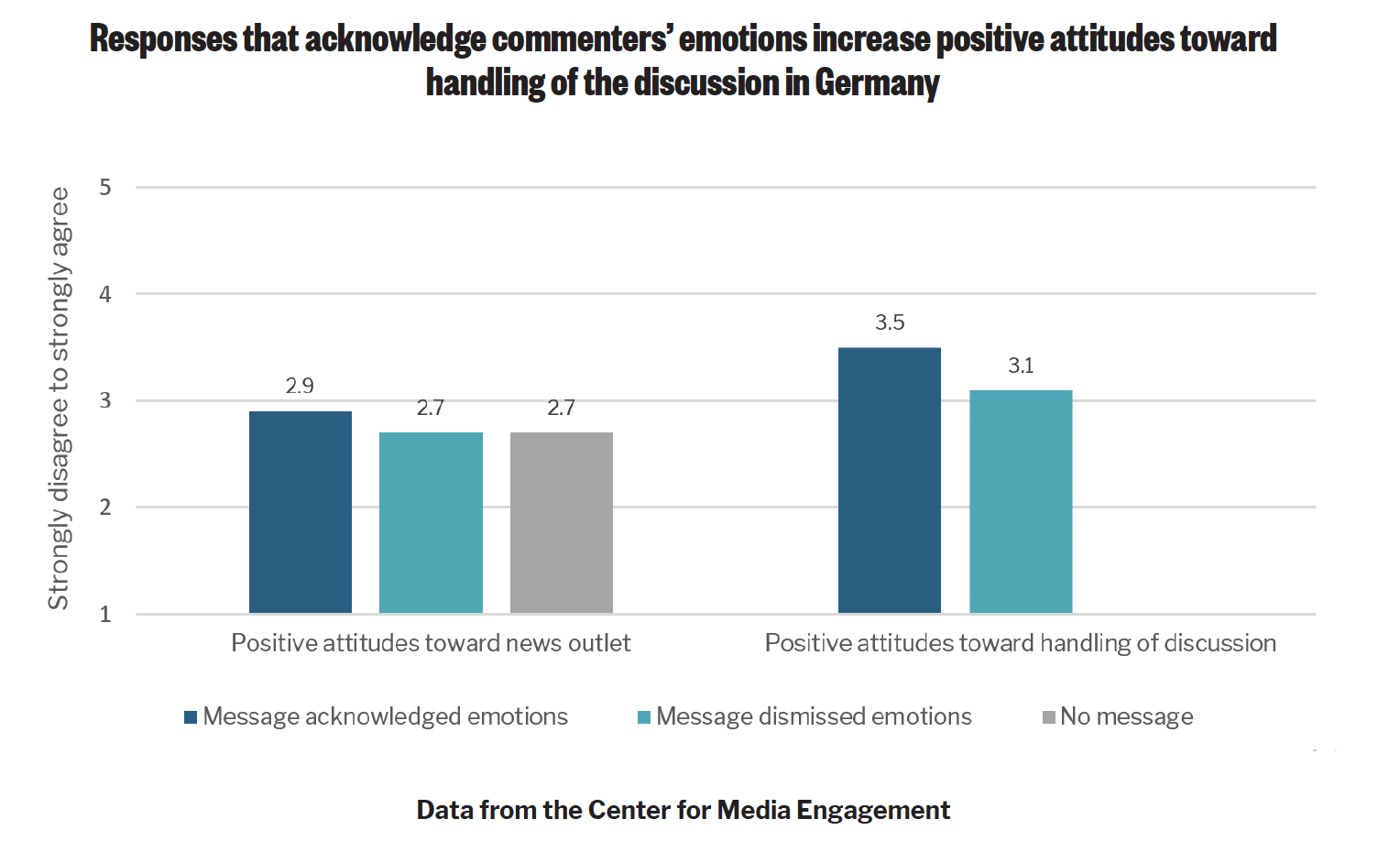

In the both countries, participants exposed to the response that acknowledged – rather than dismissed – the commenters’ emotions had more positive attitudes toward the news outlet and its handling of the comment thread, just like in Experiment 1. In both the U.S. and Germany, responses that acknowledged emotions were more effective regardless of whether a journalist or another commenter posted them. In the U.S., it did not matter whether the online conversation was uncivil, impolite, or civil – the results were the same. But, in Germany, civil discussions led to more positive attitudes toward the news outlet, regardless of what type of response to the discussion was used. All results held up regardless of the topic of the posts, which was either about immigration/refugees or the #MeToo movement that exposed widespread sexual abuse and harassment of women.7

METHODOLOGY

Experiment 1

Participants were recruited through Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (MTurk) platform, an online site of self-selected participants who perform small tasks.9 Participants had to be at least 18 years old, reside in the United States and consent to take the survey.10 A total of 798 participants met these criteria. They were paid $1 each to complete the survey, which took about 10 minutes.

Participants were shown what appeared to be a Facebook news post from The Associated Press with a photograph, a headline, and three comments posted on it. In all cases, the first comment on the Facebook post responded civilly to the topic of the post, the second comment impolitely criticized the first commenter, and the third comment came from an AP moderator who was attempting to manage the impoliteness.11 The first two comments were always the same, but the moderator’s comment varied across experimental conditions. Participants were randomly assigned to see a moderator’s comment that either acknowledged the upset commenter’s emotions or that dismissed that person’s emotions. Each participant saw a climate change post and then an immigration post. This was done to ensure the moderator’s message worked effectively across two topics. However, in the analysis reported here, the two topics were combined because no significant difference was found between them.

After seeing the Facebook posts, participants answered questions about their attitudes toward the AP12 and its handling of the impoliteness.13

Experiment 2

Participants in the U.S. and Germany were recruited through Dynata, an international survey company that provides researchers with access to panels that aim to represent the demographics of the adult population in that country. Participants had to be at least 18 years old, reside in the respective country, and consent to participate in the study. A total of 1,164 people in the U.S. and 1,154 people in Germany met these criteria.14

Participants saw what appeared to be a Facebook page from Reuters that contained a photograph, a headline, and comments. Two commenters were discussing the post civilly, uncivilly, or impolitely. Then, in some cases, a third comment responded to the discussion. This comment came from a Reuters’ journalist, from another commenter, or was absent in the control condition. People either saw a post about the #MeToo movement or about immigration/refugees.

After seeing the Facebook post, participants answered questions about their attitudes toward Reuters15 and its handling of the discussion.16 The Facebook posts and questions were translated into German by German-speaking researchers.

SUGGESTED CITATION:

Masullo, Gina M., Riedl, Martin J., Ziegele, Marc, Naab, Teresa, Jost, Pablo, and Huang, Q. Elyse. (2021, March). Journalist engagement in Facebook comments: Try acknowledging commenters’ emotions. Center for Media Engagement. https://mediaengagement.org/research/journalist-engagement-in-facebook-comments

- Stroud, N.J., Scacco, J.M., Muddiman, A., & Curry, A. (2014, September). Journalist involvement in comment sections. Center for Media Engagement. https://mediaengagement.org/research/journalist-involvement/; Stroud, N. J., Scacco, J. M., Muddiman, A., & Curry, A. L. (2015). Changing deliberative norms on news organizations’ Facebook sites. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 20(2), 188–203; See also Ziegele, M., Jost, P., Bormann, M., & Heinbach, D. (2018). Journalistic counter-voices in comment sections: Patterns, determinants, and potential consequences of interactive moderation of uncivil user comments. SCM Studies in Communication and Media, 7(4), 525-554. [↩]

- Chen, G. M., & Pain, P. (2016, August). Journalists and online comments. Center for Media Engagement. https://mediaengagement.org/research/journalists-and-online-comments; Chen, G. M., & Pain, P. (2017). Normalizing online comments, Journalism Practice, 11(7), 876–892. [↩]

- The message that acknowledged the impolite commenter’s emotions is a high-person-centered message, while the message that dismissed that impolite commenter’s emotion is a low-person-centered message. These are based on the verbal-person-centered theory of social supportive outcomes. See Burleson, B. R. (2010). Explaining recipient responses to supportive messages: Development and test of the dual-process theory. In S.W. Smith & S. R. Wilson (Eds.), New Directions in Interpersonal Communication Research (pp. 159–179). Sage.[↩]

- We defined uncivil comments as containing stereotypes or threats to democracy, impolite comments as containing profanity or name-calling, and civil comments as containing none of these, in accordance with Papacharissi, Z. (2004). Democracy online: Civility, politeness, and the democratic potential of online political discussion groups. New Media & Society, 6(2), 259–283. [↩]

- For the first experiment, the mock Facebook pages were created using PrankMeNot, an online Facebook status generator: http://www.prankmenot.com/. For Experiment 2, we created the mock Facebook pages using Photoshop. [↩]

- This was tested using two multi-factorial ANOVAs with repeated measures. Journalist’s message type (either acknowledging emotions or dismissing emotions) showed a significant main effect on positive attitudes toward the news outlet, [F(1, 794) = 9.34,η2 = 0.02, p = .002], and positive attitudes toward the handling of the impoliteness, [F(1, 794) = 16.72, η = 0.02, p < .001]. For these analyses, we tested interactions between the message type and political beliefs and attitudes toward the two topics of the news posts (climate change and immigration) to ensure results did not change based on these factors. No significant interactions were found, so these interactions were dropped from the models reported here. All models also treated the topic of the news posted as a within-subjects variable subjected to repeated measures analyses. This was done to test robustness of results across topics, not because we expected differences and, indeed, no significant differences were found. Each model also included two additional between-subjects variables that are outside the scope of this report. These were whether the journalist’s message consoled the person being attacked, or confronted the attacker, and the stance toward the news topic (e.g., pro or con the belief that climate change is real). No significant main effects were found for stance. However, a significant main effect was found that showed confronting, rather than consoling, messages led to more positive attitudes toward handling of the impoliteness, [F(1, 794) = 7.09, η2 = 0.01, p = .01] , but no main effects were found for the other variable. [↩]

- This was tested using two multi-factorial ANOVAs in both the U.S. and Germany. In the U.S., message type (either acknowledging emotions or dismissing emotions) showed a significant main effect on positive attitudes toward the news outlet, [F(2, 1158) = 8.82, η2 = 0.01, p < .001], and on positive attitudes toward the handling of the discussion, [F(1, 924) = 47.29, η2 = 0.05, p < .001]. The same model was tested in Germany, and it showed a significant main effect on positive attitudes toward the news outlet, [F(2, 1148) = 3.9, η2 = 0.01, p = .004], and on positive attitudes toward the handling of the discussion, [F(1, 911) = 35.29, η2 = 0.04, p < .001.] Sidak post hoc corrections were used for pairwise comparisons. In both countries, each model also tested tone of the discussion (civil, uncivil, or impolite) and person responding (journalist, another commenter, or no response) as additional between-subjects’ variables. In the U.S. neither tone nor person responding produced significant main effects. In Germany, person responding did not produce a significant effect, but tone of the discussion did. In Germany, civil discussions led to an average rating of 2.9 on the 5-point scale measuring positive attitudes toward the news outlet. This rating was significantly different that average rating for impolite discussions (M = 2.6, SE = 0.05, p = .003) but not than the mean for uncivil discussions (M = 2.8, SE = 0.05, p = .40). In both countries, results held up regardless whether the topic of the discussion with the #MeToo movement or refugees/immigration. [↩]

- The mean for no moderation was 2.71 and the mean for the message that dismissed emotions was 2.72, but they appear the same on the graph because of rounding. [↩]

- Paolacci, G., J. Chandler, & P. G. Ipeirotis. 2010. Running experiments on amazon mechanical turk. Judgment and Decision Making, 5 (5), 411–419.[↩]

- This project was part of a larger project that received Institutional Review Board approval from The University of Texas at Austin on November 26, 2018. [↩]

- Students in the first author’s COM 370 Online Incivility course helped generate ideas for some of the comments. The comments for both experiments were also created using a multi-step process with 508 pretest participants. They were paid $0.50 on Amazon Mechanical Turk. Some participants created comments that fit the criteria of the experiment, and others rated these comments to ensure they fit the message conditions we sought. This testing was an iterative process done across four separate pretests to ensure reliability. Ultimately, a series of t tests showed that the comments that acknowledged commenter’s emotions were perceived as significantly different than the comments that dismissed their emotions. Participants in pretest 1 (n = 25) were 39.5 years old on average (SD = 9.52), and 48% were male, and 80% were white. Pretest 2 participants (n = 207) were 34.09 years old on average (SD = 11.11), and 57.5% were male, and 81.6% were white. For the third pretest (n = 72), participants were 36.42 years old on average (SD = 11.61), and 62.5% were male, and 70.8% were white. Pretest 4 participants were 34.28 years old on average (SD = 11.49), and 60.3% were male, and 69.1% were white. The authors thank Alanis N. King for creating the comments for Experiment 1. [↩]

- These questions were adapted from Chen, P. S., Wilson, N., Chen, G.M. & Chang, C. (2015). Longer higher quality videos preferred by news viewers, Newspaper Research Journal, 36(2), 212–224; Chock, T. M., Wolf, J.M., Chen, G.M., Schweisberger, V.N., Wang, Y., (2013). Social media features attract college students to news websites, Newspaper Research Journal, 34(4), 96–108. Participants rated on a 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) scale their level of agreement or disagreement regarding the following: “I find the content on this site to be engaging,” “The time I spent on this page is valuable to me in gathering news and information,” “I would like to visit this news organization’s Facebook page again,” “I would like to share content from this news organization’s Facebook page,” “This Facebook page is what I expect from a professional news organization,” “I rate this news organization’s Facebook page favorably,” and “I like The Associated Press’ Facebook page.” Responses were averaged into separate indices for the climate change and immigration posts: (climate change, M = 4.12, SD = 1.58, Cronbach’s α = .94; immigration, M = 3.97, SD = 1.70, Cronbach’s α = .96). [↩]

- Positive attitudes toward how the impoliteness was handled was measured using ratings on the same 1 to 7 scale regarding one statement: “I thought The Associated Press’ moderator did a good job of engaging in the comment stream,” (climate change, M = 5.37, SD = 1.75; immigration, M = 5.06, SD = 1.80). [↩]

- Positive attitudes toward how the impoliteness was handled was measured using ratings on the same 1 to 7 scale regarding one statement: “I thought The Associated Press’ moderator did a good job of engaging in the comment stream,” (climate change, M = 5.37, SD = 1.75; immigration, M = 5.06, SD = 1.80). [↩]

- Positive attitudes toward Reuters was measured using five statements similar to those in Experiment 1. Participants rated on a 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) scale, their agreement or disagreement with the following: “I would like to visit the Reuters’ Facebook page again,” “I would like to share content from the Reuters’ Facebook page,” “This Reuters’ Facebook page is what I expect from a professional news organization,” “I rate the Reuters’ Facebook page favorably,” and “I like the Reuters’ Facebook page.” Response were averaged into separate indices for each country, (Germany: M = 2.78, SD = 1.03, α = .94; U.S.: M = 2.82, SD = 1.05, α = .93). [↩]

- Positive attitudes toward the discussion was measured using different questions, depending on whether a journalist or another commenter responded to the discussion. If a journalist had responded, they rated their attitudes on a 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) scale for two items, “The Reuters moderator did a good job of engaging in the comment stream” and “I liked how the Reuters moderator responded to the comments.” If another commenter responded, they rated their attitudes on the same scale for two different items: “The user who intervened in the discussion did a good job of engaging in the comment stream” and “I liked how the user who intervened in the discussion responded to the comments.” Ultimately, the items were combined into a single variable for each country (Germany: M = 3.31, SD = 1.02; U.S.: M = 3.28, SD = 1.12). [↩]