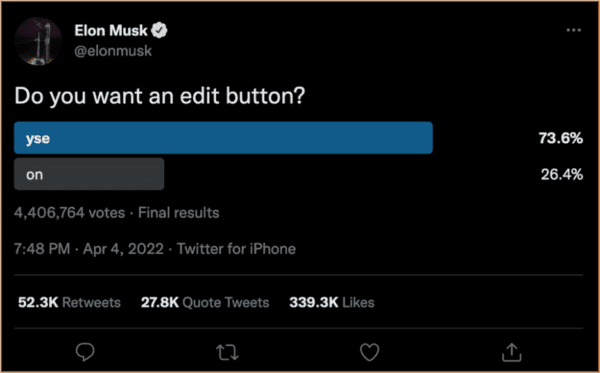

On April 4, 2022, billionaire business and tech mogul Elon Musk published a Twitter poll with a simple question: Do you want an edit button (Musk, 2022)? The resounding answer: “yse” – a sly, tongue-in-cheek response indicating what would come from a Musk-owned Twitter. At the time, Musk was already the majority stakeholder of the social media company. Ten days later, the Tesla CEO offered to purchase the platform. Although the acquisition would be mired with legal complications in the months after, culminating in Musk’s intention to terminate the agreement by early July and then finally agree to purchase it (again), the results of the original survey proved critical. For reference, look no further than now-former Twitter CEO Parag Agrawal, who “retweeted Musk’s tweet shortly after with a caption saying: ‘The consequences of this poll will be important. Please vote carefully’” (Duffy, 2022). Ultimately, 73.6% of the poll’s 4.4 million Twitter respondents selected the misspelled option for “yes,” and on September 1, Twitter announced testing for a new “Edit Tweet” feature (Musk, 2022 and Twitter, 2022). Despite the apparent popularity for the edit feature, such a potential feature raises significant ethical questions about the integrity of correcting the digital record, especially in an era marked by online sleuthing, exposing, and “canceling.”

Proponents of editing tweets, seemingly a significant portion of the platform’s users, have requested this option for years (Conger, 2022). After all, Facebook and Instagram, both owned by parent company Meta, already have an edit feature for posts. While fixing typos and adding forgotten tags attract the most attention, savvy journalists might rejoice in a new ability to quickly rectify false information. A breaking news story, like the 2013 Boston Marathon bombing for example, might be live-tweeted by reporters using social media for crowdsourcing. In that case, journalists at Buzzfeed and other digital outlets initially identified a missing student as a police suspect (Shih, 2013). However, while the rumor circulated online with ferocity, the accusation was later revealed to be false. Although these news sites issued corrections the next day, millions of people who did not follow up on the story possibly remained misinformed by only attending to the original tweets. If journalists could edit their tweets, the argument might go, mistakes like this could be quickly corrected on the app they originated from. Instead, the current option only allows for news accounts to delete the tweets entirely, which comes with its own ethical conundrums, since deleting tweets bypasses public accountability for errors by disappearing the incorrect content quietly and permanently.

Critics of the new edit feature are concerned about other ethical dilemmas that may arise if this function becomes fully implemented in the rapid and dynamic ecosystem of Twitter. For example, some are concerned about whether editing tweets will lead to new forms of delayed self-censorship. One can imagine that much individual restraint already exists on the platform, leading to users concealing their opinions on controversial subjects. During the initial testing of the edit feature, Twitter argued that the ability to edit will make tweeting “feel more approachable and less stressful” (Twitter, 2022). Others, however, are more convinced that tweeters will publish contentious positions, receive pushback from other users seeing the tweet, and then edit the tweet to be more benign. In such a scenario, “Defund the police” becomes “Rethink police budgets,” and “Make America Great Again” becomes “God Bless America,” all without notice of the original content that provoked certain responses. While individual citizens engaging in forms of self-censorship already blurs one’s genuine position, the damage in a democratic society would be exacerbated when politicians on Twitter do the same. For example, during the 2022 election cycle, Republican candidates have shown a willingness to scrub anti-abortion positions from their campaign websites (McCammond & Solender, 2022). At best, editing tweets in this way could lead to softening emotive discourse. At worst, it could result in a confused public that can’t trust their politicians to hold firm to their beliefs when criticism arises.

Similarly, the new edit feature creates a potential for risk when it comes to editing tweets that have been retweeted. In other words, what happens when a user retweets a post, generally expressing some form of endorsement, that is later edited to alter the core meaning of the original tweet? Surely a retweet isn’t always a note of support, but it at least links two tweeters interested in similar topics. Trouble emerges when internet trolls, for instance, post a link to a news article, receive several retweets that boost the content, then edit the tweet to include inappropriate or NSFW content. In such a case, Twitter users may be unfairly reprimanded for having content on their feed that they never intended to endorse, or they might be observed and judged by others as retweeting objectional content. At the very least, the individual retweeting the content has not consented to retweet the edited content, whether their retweet is critical or supportive. The nuances of criticism and support are only muddied further if one comments on a post through a retweet, only to have the original tweet’s content edited at a later time.

In the face of such criticisms, Twitter has toyed with implementing certain guardrails to try to prevent abuse of the new edit feature. Tweets will be editable only for 30 minutes after posting and edited tweets will appear with an icon, timestamp, and link to their “Edit History” to “protect the integrity of the conversation and create a publicly accessible record of what was said” (Twitter, 2022). However, despite these stipulations, some nonetheless worry that they are not enough. Indeed, while a semi-visible “edit history” may dampen the effect of tweeters attempting to make major edits quietly, many users are likely to scroll past without investigating further. The content of tweets by its very nature is short and ephemeral, and many viewers will not have the time or the patience to click into a detailed editing history of a short message.

Given the power social media companies wield in society, the policies of each platform should be scrutinized carefully. Currently, the edit feature is still being tested and its exact implementation is very uncertain. However, whether Twitter ultimately decides to roll out an edit feature fully or with additional provisions, the very process of editing something as momentary and ever-changing as one’s tweets at all raises ethical concerns related to accountability, self-censorship, and association between users. Twitter is both an ever-changing conversation and a semi-permanent archive of the ever-changing momentary thoughts and postings of millions of users. Will the edit button improve the quality of online discourse, or simply spoil the “‘receipt’ uniqueness of the platform” (Adetona, 2022), leading to more misinformation, miscommunication, and trolling in the digital era?

Discussion Questions:

- Editing tweets sounds simple. What are the most persuasive concerns with adding an editing feature?

- How does the ability to edit tweets differ from editing other social media content, like Facebook posts?

- What ethical values are in conflict when it comes to the dispute over editing tweets?

- Do you think Twitter’s proposed limitations on editing tweets are sufficient? If not, what additional restrictions would you suggest the company implement?

- After weighing all of the benefits and ethical concerns of Twitter’s proposed editing feature, do you think it should be implemented? Explain your position.

Further Information:

Adetona, Adewale [@iSlimfit]. “Why is Twitter bowing…?” Twitter, September 1, 2022, http://www.tinyurl.com/2s42uj8h

Conger, Kate. “Farewell, Typos! Twitter Unveils an Edit Button.” The New York Times, September 1, 2022. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2022/09/01/technology/twitter-edit-button.html

Duffy, Kate. “Elon Musk asks Twitter users whether they’d like an ‘edit’ button. Twitter’s CEO says results of the poll will be ‘important.’” Business Insider, April 5, 2022. Available at: https://www.businessinsider.com/elon-musk-polls-twitter-edit-button-ceo-agrawal-results-important-2022-4

McCammond, Alexi & Solender, Andrew. “The big scrub.” Axios, August 31, 2022. Available at: https://www.axios.com/2022/08/31/republicans-midterms

Musk, Elon [@elonmusk]. “Do you want an edit button?” Twitter Post. April 4, 2022. Available at: https://twitter.com/elonmusk/status/1511143607385874434

Shih, Gerry. “Boston Marathon bombings: How Twitter and Reddit got it wrong.” The Independent, April 22, 2013. Available at: https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/americas/boston-marathon-bombings-how-twitter-and-reddit-got-it-wrong-8581167.html

Twitter. “This is a test of Twitter’s new Edit Tweet feature. This is only a test.” Twitter Blog, September 1, 2022. Available at: https://blog.twitter.com/en_us/topics/product/2022/twitter-new-edit-tweet-feature-only-test

Authors:

Dex Parra, Kat Williams, & Scott R. Stroud, Ph.D.

Media Ethics Initiative

Center for Media Engagement

University of Texas at Austin

November 30, 2022

Image: Screenshot from Twitter

This case was supported by funding from the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. It can be used in unmodified PDF form in classroom or educational settings. For use in publications such as textbooks, readers, and other works, please contact the Center for Media Engagement.

Ethics Case Study © 2022 by Center for Media Engagement is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0