Hyperlinks are standard fare on news websites. They can help site visitors find more information and learn more about important issues facing their communities. And from a business perspective, hyperlinks can increase time on site. What affects whether a person clicks on a link? Certainly the topic matters, as does where a link appears on a page. Prompts and labels that introduce hyperlinks also can have an effect. Labeling links as “Most Popular,” for instance, encourages people to click on the links to see what others find interesting.

Hyperlinks can be organized and labeled in many different ways. Take The Washington Post, for example. Opinion columns are categorized on left- and right-leaning opinion pages. The opposing partisan pages are hyperlinked, with the following prompt introducing the link: “Disagree with our opinions here? Check out our (left-leaning / right-leaning) opinions.”

Hyperlink prompts are interesting from a democratic perspective. We know that people are more likely to look at information agreeing with their political viewpoint than they are to look at counter- attitudinal information, or information that opposes one’s own point of view. Could hyperlink prompts, developed based on theories from communication, political science, and psychology, lead people to look at opposing viewpoints?

The Center for Media Engagement investigated new ways of labeling hyperlinks. What if instead of “Most Popular” or “Check out our left-leaning opinions,” hyperlinks were preceded with “Follow the issues that worry you,” for example? Research suggests that messages like this can affect what articles people select and what they take away from the news.

We asked: Are there hyperlink labeling strategies that have both business and journalistic implications? We tested whether six different prompts, like “Follow the issues that worry you,” influenced citizens’ appetite for hard news content and for news from different partisan perspectives. We also examined whether these prompts increased time on site, increased the number of page views, or improved assessments of site credibility.

Results of the project signal that prompts have complicated effects. Some prompts did not have any effect on business outcomes, like time on site, and others had a negative impact. And although some prompts increased the amount of time visitors spent with hard news content, other prompts led people to see opposing political views as less legitimate. Not one prompt of those that we tested had uniformly beneficial effects.

Key Findings

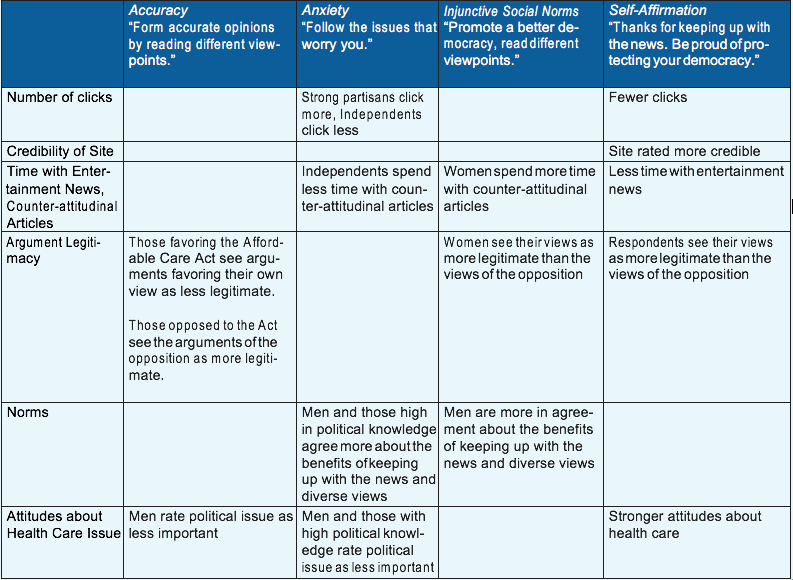

Our experimental results indicated that our prompts affected different people in different ways, leading to a mixed bag of democratic and commercial outcomes. Because of the complex nature of these results, we are not able to make any across-the-board recommendations for the use of prompts. We have provided, however, a table (see page 12) summarizing the results of our findings. This table should assist newsrooms in determining whether any of the prompts that we tested could help them reach their goals.

Implications for Newsrooms

News organizations must carefully consider their objectives, and then test hyperlink prompts before deploying them on their sites. If your only objective is to affect people’s perception of how legitimate the other side is, then an accuracy prompt like “Form accurate opinions by reading different viewpoints” would be a leading candidate. But if you were hoping that this prompt would have a business implication, such as increasing the number of clicks on your site, we don’t have any supportive evidence.

If you wanted site visitors to believe that there are many benefits from keeping up with the news and diverse views, then an anxiety prompt (“Follow the issues that worry you”) or a normative prompt (“Promote a better democracy, read different viewpoints.”) may be just the ticket, at least for some subgroups. But watch out – both prompts decrease the amount of time that some site visitors are willing to spend with counter-attitudinal articles and there is scant evidence of business implications. Finally, if you want people to see your site as more credible, try “Thanks for keeping up with the news. Be proud of protecting your democracy.” This prompt, however, also reduces the number of clicks on a site. Hardly good business. Even democratically speaking, the prompt is problematic. Although people seeing it spend less time with entertainment news compared to hard news content, they also see their own views as more legitimate.

In sum, it may seem innocuous to include a short phrase before hyperlinks, but our research indicates otherwise. The presence of a single phrase on a site can have both business and journalistic implications. And if these results are any indication, effects are far from simple. A desirable outcome, such as seeing a site as more credible, can be coupled with an undesirable one, such as fewer page views. Any change in hyperlink labeling should be carefully tested.

Introduction

News and Hyperlinking

Hyperlinking is standard practice on news webpages, having increased dramatically since the mid- 1990s.1 In the following section, we review studies on the use and effects of hyperlinks on news websites. Throughout, we emphasize what we know about how hyperlinks are organized and labeled on news websites and the influence these labels have on user behavior and perceptions.

Hyperlinking Practices

Newsrooms make extensive use of hyperlinks, whether linking to a news article, to documentation backing up a claim, or to an advertisement. The reasons for using hyperlinks are multiple. Communication scholars Tsan-Kuo Chang, Brian Southwell, and their colleagues conducted a survey of newspaper editors and television news directors to understand what they thought about hyperlinking.2 The results revealed that many believed that hyperlinking helped to provide information to readers, to offer alternative perspectives, and to assist site visitors in forming better understandings of the news.

There are many standard practices in the use of hyperlinking in newsrooms. Not unexpectedly, news hyperlinks typically are internal, whether to a parent company, to other articles on the same site, or to opportunities to email newsroom staff.3 An in-depth analysis of newspapers’ hyperlinking practices related to the news surrounding Timothy McVeigh’s execution provides an important perspective about news sites’ practices.4 The research found that most hyperlinks (90%) were text-based and many (95%) appeared in the sidebars, rather than embedded in the text.

Although most news organizations employ hyperlinks, there is some variability depending on the parent organization. Stories on broadcast news sites historically have included more hyperlinks in comparison to print news stories, for instance, and citizen journalists include more links in their articles compared to online newspapers located in the same locale.5 Of particular interest for the present project is how hyperlinks are organized and presented to site visitors. To understand current practices, we analyzed the content of 107 randomly selected local television news station websites to examine their linking practices.6 Many had “Top Stories” sections prominently displayed on their homepage. These often consisted of hyperlinked stories selected by news staff. Stations also organized hyperlinks into topic-based categories (e.g. Local News, U.S. News, etc.) to facilitate visitor browsing. Groups of links typically were featured around the perimeter of the webpage.

We paid particular attention to the words, or prompts, used to describe available hyperlinks. One of the most common prompts we found was “Most Popular,” which was included on 78 percent of sites. The “Most Popular” list often was found when scrolling down the station homepage or embedded within articles featured on the site. In addition to promoting stories viewed most frequently by site visitors, some sites also provided hyperlinks to stories that were garnering the most comments (11%). Another hyperlink prompt frequently found on the sites was to “Related” or “Recommended” content. In some instances, this content was selected by newsroom staff to correspond with the topic of an article. A story about a local crime, for example, was linked to related content about other crimes in the community. In other instances, recommended hyperlinks were automatically generated to correspond with a site visitor’s browsing behavior. In total, 57 percent of sites included a “Related” or “Recommended” prompt prior to a list of hyperlinks.

Hyperlinking Effects

By directing how site visitors navigate a website, hyperlinks can affect both business and democratic outcomes.

- Time on Site

- From a business angle, existing research demonstrates that links can increase the amount of time visitors spend on a news site.7 In particular, personalized links – those that are tailored to individuals based on their previous browsing behavior – have the potential to increase users’ engagement with a website.8

- Learning

- From a democratic angle, the presence of interactive online features, like hyperlinks, can help citizens to learn about politics.9 A series of studies demonstrate that hyperlinked news helps people learn in a different way than non-hyperlinked news.10 Those using non-hyperlinked news retain more factual information compared to those interacting with a hyperlinked site. Experienced browsers using a hyperlinked news site, however, gain more “knowledge structure density,” or an understanding of how various concepts fit together. Those with higher levels of knowledge structure density are more likely to see that diverse political topics, such as international relations, gasoline prices, and environmental protection, are related to one another.11 The rationale is that experienced browsers use hyperlinks to seek more information that gives them a greater perspective on how topics relate.

- Perceptions of Credibility

- As news organizations deploy hyperlinks on their sites, one potential concern is whether the presence of hyperlinks affects perceptions of site credibility. One study asked respondents to evaluate six different websites for how credible they found each site.12 Impressions of how easy it was to access and share information, an indicator of a site’s hyperlinking aptitude, related to seeing aggregator sites Yahoo! News and Google News as more credible. Ease of accessing information was unrelated to assessments of site credibility for traditional news sites like the New York Times and USA Today, however. In sum, hyperlinks can positively relate to credibility but are not guaranteed to do so.

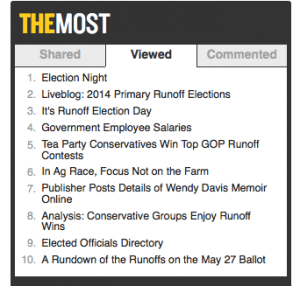

- Popularity Does Not Equal Importance…

- The possibility of tracking hyperlink use has provided new opportunities for news organizations to understand site visitors’ preferences. For example, do the articles viewed most frequently by site visitors match the articles featured on news websites? Research says no. Northwestern University professor Pablo Boczkowski and Limor Peer from Yale University compared “Most Popular” stories on news sites with stories prominently displayed on the sites.13 Visitors selected more soft news stories than the news sites featured. This study suggests a potential mismatch between the priorities of online news editors and the priorities of site visitors.

- … But Popularity Fuels Popularity

- Boczkowski and Peer’s findings show that articles appearing in “Most Popular” lists do not always link to hard news content. We also know that articles featured in “Most Popular” lists can attract even more page views. In one clever study, participants browsed a website consisting of seven news articles.14 Although the articles remained the same for each study participant, the number of times that each article had been viewed was randomly varied. For example, some study participants saw that an article titled “High school principal ponders loss of job” had been viewed by 64 others. Other study participants, however, saw that the same article had been viewed by 232 others. The more frequently each article was said to have been viewed, the more likely study participants were to select the article. Interestingly, least-seen articles also were more likely to be selected by study participants. The results demonstrate that information accompanying hyperlinks can affect decisions about clicking on a news link. Here, “Most Popular” content can increase page views.

Preferences for Like-minded Information

Research over the past several years consistently has demonstrated that people are more likely to select media messages that match their beliefs and to avoid messages that contradict their views, a behavior known as selective exposure.15

This is not to say that people always avoid information that runs contrary to their views. Although people do prefer like-minded messages, they still view messages with an opposing point of view from time to time.16 Yet when encountering messages with which one disagrees, people do not always process the messages in an unbiased manner. Indeed, some research has shown that when faced with counter-attitudinal messages, people can become even more convinced of the validity of their own views and more certain that the opposition’s take is objectionable.17 This is known as biased processing, where the interpretation of information is filtered based on one’s personal preferences.

Questions have arisen about how to curtail selective exposure and biased processing of political information. Few research studies have examined how to use prompts in a news setting in a way that reduces biased processing. One exception is a study conducted by Edith Manosevitch.18

Manosevitch analyzed how the inclusion of different prompts on a news website would affect what people thought. She analyzed what happened when visitors encountered two different prompts on a news webpage. The first, labeled a reflective cue, stated that the news organization was “committed to thinking about issues with readers.” The second, labeled a citizenship cue, said that the news organization was “committed to democracy and citizenship.” Citizens who saw the reflective cue gave more thought to the article and perceived the media to be more important to citizens than people who did not see the reflective cue. These results, however, were dependent on the topic of the news story – they appeared when the topic was Social Security, but disappeared for same-sex marriage. Although the results were not consistent, the overall findings are encouraging: Prompts have the potential to affect how people reason when approaching news articles.

The Study

To begin the Center for Media Engagement’s investigation into hyperlinking practices, we first combed through the research literature to find previous strategies that have worked to encourage people to seek out and think about information in unbiased ways. Our search yielded six different theoretical approaches. Based on this previous research, we developed a series of hyperlink prompts that could be employed on news websites. In particular, we designed prompts about:

- Taking pride in one’s values and actions. Self-affirmation research suggests that people with a bolstered sense of self-worth are more open to views unlike their own.19

- What good citizens should do. This is a type of injunctive social norm, or statement about socially approved or disapproved attitudes and behaviors. Reminding people of these norms can affect their attitudes and behaviors.20

- How looking at different points of view can help one form more accurate opinions. Motivating people to think about accuracy can lead to more balanced consideration of counter-attitudinal views, research shows.21

- Preparation for situations where people would want to display their news understanding. When people are accountable to others, they are more evenhanded in their consideration of information.22

- What other people do. Highlighting descriptive social norms, or factual descriptions of others’ behaviors or attitudes, can motivate people to reconsider their own thoughts and actions.23

- Fears and anxieties. Those feeling anxious are more inclined to spend time with news and information both for and against their views.24 Fear combined with guidance on how to resolve the fear is especially effective at motivating behavior.25

Based on these theories and research, we developed six different news prompts. Below, we provide an overview of our research, present the literature supporting each approach and then summarize our study’s findings.

To test our news hyperlink prompts, we conducted a pilot test followed by a laboratory experiment. We describe each, and provide an overview of our findings, in the following section. Full details about the studies and samples can be found in the appendix.

Pilot Test

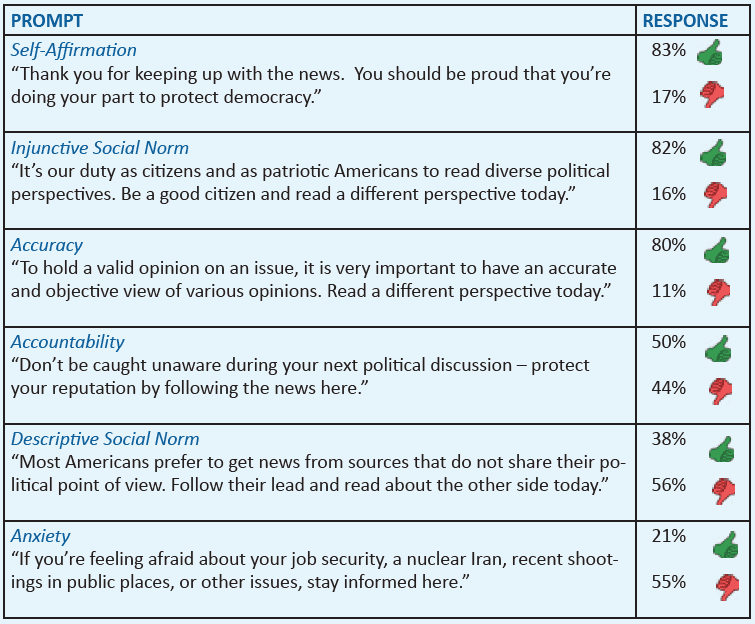

As a first step, we showed people the prompts shown in the table below and asked them to write a paragraph about their reactions. We wanted to understand people’s gut reactions to these words and phrases. We then categorized responses as favorable, meaning that the response expressed agreement with the prompt’s basic ideas, unfavorable, meaning that the response argued against the prompt, or other, which included responses not directly engaging the prompt. As shown in the summary table below, responses varied widely. Some prompts received favorable reviews, while others sparked substantially less favorable reactions.

Based on these results, we narrowed our focus from six prompts to four by eliminating the accountability and descriptive social norm prompts. Although the anxiety prompt was not favorably reviewed in the pilot test, we opted to continue with it given the volume of literature suggesting that it should work.

Laboratory Test

With revised versions of the four remaining prompts, we conducted an online experiment with 681 participants to find out whether the prompts affected people’s behavior.

All participants first answered a series of questions, including items asking them to report their attitudes about the Affordable Health Care Act. We chose this issue strategically and discuss our reasons in the appendix. Later, participants were asked to browse a website. All participants first saw an article matching their health care views. Those favoring the Affordable Care Act saw an article favoring the act and vice versa for those opposed to the legislation.

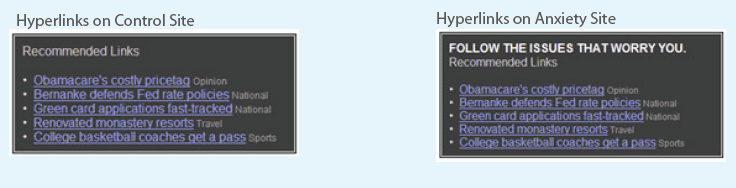

To design the study, we created a mock news website called Political Beat. In fact, we created five different versions of Political Beat. The versions were identical in every way but one: each version included a different prompt preceding a list of hyperlinks. In addition, one version included no prompt preceding the list of links. We refer to this version as the “control site.” At random, study participants browsed one of these five websites. An image of the full website can be found in the appendix; here we show two examples of the only part of the site that varied: the way in which the hyperlinks were labeled.

We tested whether the prompts changed how people used the site by unobtrusively tracking their online behavior. After participants finished browsing the website, we asked them a host of questions to see if the prompts affected their reactions to the site, views about those holding opposing views, norms about news use, and how credible they found the site.

We tested whether the prompts changed how people used the site by unobtrusively tracking their online behavior. After participants finished browsing the website, we asked them a host of questions to see if the prompts affected their reactions to the site, views about those holding opposing views, norms about news use, and how credible they found the site.

We also analyzed whether specific kinds of people reacted differently to the prompts. In particular, we looked at whether reactions to the prompts differed among: (1) those with high versus low political knowledge, (2) those with strong, weak, and no partisan leanings (3) those in favor of or opposed to the Affordable Care Act (the focal issue on the mock site), and (4) males versus females.

Our test is ambitious. We wanted to find a prompt that did it all: increased the number of links clicked on a site, improved assessments of site credibility, increased time with hard news over entertainment, increased time with political views unlike one’s own, led people to see oppositional views as more legitimate – even if they disagreed, and greater endorsement of beliefs about the benefits of news and exposure to diverse views. A prompt having even some of these outcomes and no negative effects could be seen as successful.

Lab Test Findings

Below, we summarize our findings. The results show what happens when we compare the attitudes and behaviors of those surfing the website with the various prompts to those surfing the website without any prompt. We include only statistically significant findings.

As the summary of effects illustrates, the prompts produced complex outcomes. For example, the anxiety prompt encouraged more clicks by partisans, but less clicks by those with weaker or no partisan views. In short, there was a pattern of prompts having both positive and negative effects. Because of this, we cannot recommend the use of any of these prompts in a wholesale fashion. Newsrooms should carefully consider their objectives, and in consultation with the table below, test any prompts to ensure that they are achieving their intended effects.

NOTE: In the pages below the table, we provide more detailed analyses and conclusions about our results for interested readers.

In-Depth Analysis of Pilot Test and Lab Results

For interested readers, we have provided here detailed analyses of the effects summarized in the table on the previous page. In the sections that follow, you will find explanations of the results for each of the six original prompts, as well as an overall conclusion to this study that seeks to explain its complex findings.

Accountability

When people feel accountable for their opinions or actions, they think and behave differently than they might otherwise.26 In particular, people expecting to be held accountable more carefully scrutinize arguments, rather than dismissing counter-attitudinal arguments without adequate reflection.27 We wondered if the same feeling could be inspired by a prompt on a news website.

To evoke feelings of accountability, past studies have told experimental participants to expect to explain and justify their opinions face-to-face with another person later in the study.28 These studies created the expectation among participants that they would be held accountable for their views and opinions in a one-on-one situation. One study, for example, increased feelings of accountability among respondents by telling them: “In the communication phase of the experiment you will be asked to explain and justify your opinions to another subject.”29

Pilot Test

Based on this research, we developed a prompt designed to increase feelings of accountability. Since our study did not actually involve subsequent interactions, we could not state that the users would be engaging in a conversation at a later point in time. Instead, we simply reminded users that they could be held accountable and that they would want to ensure that they had the correct information if/when that occurred.

We developed the following prompt:

ACCOUNTABILITY PILOT TEST PROMPT: “Don’t be caught unaware during your next political discussion – protect your reputation by following the news here.”

A pilot test with 32 respondents revealed some potential problems with this prompt. Although 50 percent wrote favorable responses, 44 percent counter-argued the prompt. For example, one respondent writing in support of the prompt noted: “I think it is saying that it’s best to be aware of the latest news before you get into conversation about politics and wind up looking like a boob because you are not informed.”

Yet counter-arguments we encountered included the following: “The most important reason to be politically aware is to not look dumb when talking to your friends about it. That’s kind of a silly reason. One should be politically aware so that they can make educated voting decisions and be aware of that is happening in your town, county, state, country.”

Based on respondents’ mixed reactions to this prompt, we did not further pursue it in the full laboratory test. It is possible that the threat of one-on-one interaction that took place in prior research is necessary for accountability to affect reactions.

Accuracy

As humans, we generally strive to be “right.” It doesn’t feel good to be proven wrong. To prevent this, and the disappointment that comes with it, we often have goals to be as accurate as possible. Psychologists have discovered that accuracy goals have interesting effects on us – they make us seek out a greater variety of information and lead us to think more carefully about our opinions.30

Accuracy goals have been induced in numerous ways in prior research. One noteworthy example comes from University of Wisconsin-Madison scholar Young Mie Kim, who told study participants: “To make a valid voting decision, it is very important to have an accurate and objective view of candidates.”31 Kim found that an accuracy focus led people to conduct a more unbiased search for information – exactly what we hope to find in the current project.

Pilot Test

We used wording similar to Kim in our pilot test:

ACCURACY PILOT TEST PROMPT: “To hold a valid opinion on an issue, it is very important to have an accurate and objective view of various opinions. Read a different perspective today.”

In the pilot test, respondents reacted positively to the accuracy prompt. Of the 102 people who provided their reaction, 80 percent of the reactions were favorable, 11 percent counter-argued the prompt, and 9 percent were unrelated. For example, one respondent wrote: “There is a lot of truth in the statement that we should all make ourselves aware of different opinions. Sometimes learning about a different perspective only strengthens our own position as we learn more information about why our own opinion is the right one (by learning about faulty reasons others have). Sometimes, however, exposing ourselves to different perspectives can change our own opinions for the better.”

Based on these results, we moved forward with testing the accuracy prompt in the full laboratory setting.

Lab Test

For the lab test, we shortened the prompt considerably in order to make it more usable by a news site with limited space:

ACCURACY LAB TEST PROMPT: “Form accurate opinions by reading different viewpoints.”

Overall, no main effects emerged when comparing the accuracy condition, where respondents browsed the site containing the above prompt, and the control condition, where respondents browsed a site identical in all ways except not containing the prompt above. The prompt did, however, have an effect that depended on respondents’ sex and opinions about the Affordable Care Act.

Time and Clicks

Compared to those receiving no prompt, those receiving the accuracy prompt were no different in terms of where they clicked and how long they spent with the articles.

Emotions and Credibility

There also were no differences between the accuracy and control conditions in respondents’ emotional responses to the website or their perceptions of the site’s credibility.

Health Care Attitudes

There were no differences between the control and accuracy conditions in terms of participants’ attitudes toward health care and the strength of these attitudes. One difference emerged in terms of the perceived importance of health care, but it was dependent on the respondent’s sex.32 As shown in the figure on the full report, men in the accuracy condition rated the health care legislation as less important than men in the control condition. The average importance rating was similar for women regardless of whether they saw the website without a prompt or a website with the accuracy prompt.

Legitimacy

The accuracy prompt affected how people rated the legitimacy of their views and the views of others compared to those seeing the website without a prompt. The effects depended on whether respondents favored or opposed the health care legislation, however. For those who opposed the legislation, the accuracy prompt led opponents to see greater merit in the views of supporters who favor the law.33 The accuracy prompt led those favoring the legislation to evaluate arguments favoring the law a bit less positively.34

Norms

There were no differences between the accuracy condition and the control condition in what respondents thought about norms regarding keeping up with the news and looking at multiple points of view.

Anxiety

Negativity has a bad reputation. Political attack ads and stressful current events often make people anxious and fearful about politics. But what if negative feelings lead to positive political behaviors? Recent research suggests exactly this.35 Namely, citizens who feel anxious about politics and current events are likely to look at political information from many perspectives, rather than sticking to information with which they agree. We wanted to know whether news outlets could use this important finding to encourage citizens to look at political information from other political views. Can online news outlets use anxiety about politics to encourage news users to seek out more information?

Experimental work on emotions has manipulated anxiety in a variety of ways. One way is to prompt respondents with a version of the following: “We would like you to describe something that has made you feel afraid when thinking about current events. Please describe how you felt as vividly and in as much detail as possible. Think about important issues facing the nation, politics, and international affairs. It is okay if you don’t remember all the details, just be specific about what exactly it was that made you afraid and what it felt like to be afraid. Take a few minutes to write out your answer.”36 We draw upon the language of prior work on anxiety which suggests that the most powerful prompt would not only induce anxiety, but also would provide a way to remedy the feeling.37

Pilot Test

For the pilot test, we used the following prompt:

ANXIETY PILOT TEST PROMPT: “If you’re feeling afraid about your job security, a nuclear Iran, recent shootings in public places, or other issues, stay informed here.”

The first part of our pilot test was to examine whether the issues we identified as most troubling in the prompt were the issues citizens actually believed were anxiety-producing. We asked a subset of respondents (n=31) who had not seen the prompt to tell us about something that made them feel afraid, using the question wording from prior literature reviewed above. The results were clear: the issues mentioned in the prompt were the most common issues mentioned by respondents as to what made them fearful. Fifty-two percent of the responses were about the economy, recent shootings, or a nuclear Iran. Although it seemed that we correctly captured anxiety-producing issues, the pilot test indicated troubling signs for the anxiety prompt. Of the 33 participants that saw this prompt, 55 percent had unfavorable reactions, 21 percent wrote favorable responses, and 24 percent noted something unrelated.

Here is a response from one respondent that demonstrates the sort of counter-argument we saw: “This statement makes me think about how much fear is put into our minds from news media. There is hardly ever any ‘good’ news in the media. There is a huge disproportion when it comes to the good and bad news we are fed every day. I feel like a big part of this is to drive us to consume more products. We are given bad news and filled with fear and then shown ads about how great our lives would be if we owned a specific product.”

The negative response to the prompt dampened our optimism about the potential for this prompt to encourage diverse news exposure. Given the extensive research suggesting that anxiety can have positive effects, however, we proceeded with the full laboratory test despite the pilot test results.

Lab Test

For the full laboratory test, we revised the prompt to be shorter and more general:

ANXIETY LAB TEST PROMPT: “Follow the issues that worry you.”

As with the accuracy prompt, all effects of this prompt were contingent on who was browsing the site – whether the person was male or female, strongly partisan or not, and politically knowledgeable or not.

Time and Clicks

The anxiety prompt affected how respondents spent their time on the site, but it depended on whether study participants identified as strong partisans, weak or leaning partisans, or as Independents. As shown in the following figure, Independents spent less time with counter-attitudinal articles on the site with the anxiety prompt compared to Independents seeing a site without a prompt. The pattern reverses as the strength of partisanship increases such that strong partisans spent slightly more time with counter-attitudinal articles when the site included the anxiety prompt compared to a site without a prompt.38

A similar relationship appears when looking at the number of clicks, as opposed to the amount of time spent with counter-attitudinal articles. Although the anxiety prompt increased the number of clicks among strong partisans, it decreased the number of clicks among Independents.39

Emotions and Credibility

There were no differences between the anxiety and control conditions in terms of respondents’ emotional responses to the website and their perceptions of site credibility.

Health Care Attitudes

Those in the anxiety condition and those in the control condition did not differ in their attitudes toward the health care legislation, nor did they differ in the strength of their attitudes about the legislation. Some differences did emerge on how important participants’ found the legislation. These differences were conditional, however. They depended on the participants’ sex and political knowledge. We explain each in turn.

Men in the anxiety condition rated the legislation as less important than men in the control condition; no differences appeared for women.40 When those with high political knowledge were exposed to the anxiety prompt, they rated health care as less important compared to those with similar levels of political knowledge in the control group. Those with low political knowledge displayed little difference in their ratings of the importance of the legislation – if anything, they rated health care as slightly more important when exposed to the anxiety prompt compared to those viewing the control website.41

Legitimacy

There were no differences between the anxiety and control conditions in terms of how legitimate respondents’ found arguments favoring their own view and how legitimate respondents found arguments favoring the opposition.

Norms

Respondents indicated whether they agreed or disagreed with four different statements about the importance of keeping up with the news and with different political perspectives. There were some differences in study participants’ endorsement of these normative ideas, but they were conditional based on the respondents’ sex and political knowledge. Men in the anxiety condition agreed more strongly with these normative ideas compared to men in the control condition.42 There were no significant differences in women’s endorsement of these ideas between the control and anxiety conditions. In terms of political knowledge, those with more political knowledge were more apt to endorse these norms for keeping up with the news and other points of view in the anxiety condition compared to the control.43 The difference among those with lower levels of political knowledge was not significant.

Self-Affirmation

Although pride may be one of the seven deadly sins, research suggests that it is not always such a bad thing. When we feel good about ourselves, we are more open to understanding different perspectives and giving other views a fair shake. The experience of seeing one’s self positively is what psychologist Claude Steele described as self-affirmation.44 Self-affirmation may be a key way to help people process alternative perspectives.

In comparison to many of the other prompts we considered, we found the most variability in how self-affirmation had been approached in previous research. First, participants in some studies were asked to identify and then write a paragraph about a value of importance.45 Second, participants in other studies unscrambled sentences containing words that primed values previously found to be meaningful.46 Third, in yet other analyses, participants were asked to reflect on instances that made them feel proud or that reflected positively on themselves.47

Pilot Test

As participants find many different values to be important, we created a prompt more in line with the third idea from prior literature:

SELF-AFFIRMATION PILOT TEST PROMPT: “Thank you for keeping up with the news. You should be proud that you’re doing your part to protect democracy.”

Results of the pilot test signaled the potential benefits of the prompt. Eighty-three percent of respondents (n=35) supported the prompt. Seventeen percent wrote a counter-argument. For ex- ample, one supportive respondent wrote, “You need to be aware of what is going on. If I hear about issues I know how I should vote or if I need to take action.”

Lab Test

SELF-AFFIRMATION LAB TEST PROMPT: “Thanks for keeping up with the news. Be proud of protecting your democracy.”

Time and Clicks

The self-affirmation prompt did have an effect on how participants allocated their time on the site and how many times respondents clicked on the links provided. Those viewing the self-affirmation prompt spent less time with entertainment compared to those in the control condition, who did not see any prompt before the hyperlinks.48 The self-affirmation prompt also affected the amount of time spent with counter-attitudinal articles, but the effect was dependent on participants’ strength of partisanship. Those without a major party affiliation who identified as Independents spent less time with counter-attitudinal articles when encountering the self-affirmation prompt in comparison to those not seeing a prompt (the control condition). The pattern is weaker for those with weak and leaning partisan identities. The pattern reverses for those with strong partisan identities, among whom the self-affirmation prompt modestly increases time with counter-attitudinal views.49 Those in the self-affirmation condition clicked on fewer articles in comparison to those on a website containing no prompt before the hyperlinks.50

Emotions and Credibility

Those who saw the self-affirmation prompt reported more pride and hope after viewing the website in comparison to those in the control group.51 Those in the self-affirmation condition also found the site to be more credible in comparison to those in the control condition.52

Health Care Attitudes

Women in the self-affirmation condition were more favorable toward health care legislation in comparison to women in the control condition.53 The differences for men were not statistically meaningful. There also were differences between the self-affirmation and control conditions in terms of how strongly respondents’ held their attitudes about health care. Those in the self-affirmation condition reported stronger attitudes in comparison to those in the control condition.54

Legitimacy

When looking at the perceived legitimacy of views in favor of one’s position and of views opposed to one’s position, the self-affirmation prompt again made a difference. For this measure, we looked at how legitimate respondents rated views of their own side, on average, and then how legitimate respondents rated the views of the opposition, on average. We subtracted them from one another, so that large, positive numbers indicate that a person believes that their views are far more legitimate than the view of the opposition. As shown in the figure, those in the self-affirmation condition rated their own views as more legitimate than the opposition compared to those in the control condition.55

Norms

There were no differences between those in the self-affirmation condition and those in the control condition in terms of whether they endorsed normative statements about keeping up with the news and attending to diverse political viewpoints.

Social Norms

By placing appeals to social norms on websites devoted to news, we hoped to encourage citizens to seek out more political information. We examined both injunctive social norms, statements about socially approved or disapproved attitudes and behaviors and descriptive social norms, or factual descriptions of others’ behaviors or attitudes. Hopefully, by reminding citizens of the democratic virtues of information seeking and informing them that many people already seek out information from many points of view, news organizations could both encourage users to stay on their website longer and help them learn more about current events in the process.

Pilot Test

Our first task in testing the effects of a descriptive norm was to find appropriate statistical evidence about what most people do. Data from the Pew Research Center’s Internet and American Life Project fit the bill.56 The results of a survey showed that “34% of online political users said that most of the political news and information they get online comes from sites that share their point of view- compared with 30% who typically get news from sites that don’t have a point of view, and 21% who get news from sites that differ from their point of view.” Further, “about six-in-ten (62%) say they prefer getting political news from sources that do not have a particular point of view. A quarter (25%) say they prefer getting news from sources that share their political point of view.” On the basis of these results, we devised the following prompt:

DESCRIPTIVE NORM PILOT TEST PROMPT: “Most Americans prefer to get news from sources that do not share their political point of view. Follow their lead and read about the other side today.”

On the pilot test, respondents were asked to write a paragraph about this prompt. The results of the pilot test were dismal. Fifty-six percent of respondents (n=104) counter-argued the prompt and 38 percent expressed a sentiment consistent with the prompt. For example, one respondent wrote, “If this were true Fox News would not be as popular as it is today. People watch the news from sources that share their political point of view and manipulate them in extreme fashions.”

On the basis of the dominant negative response to this prompt, we did not pursue it further in the full laboratory test. Happily, the injunctive norm prompt fared better in the pilot test.

INJUNCTIVE NORM PILOT TEST PROMPT: “It’s our duty as citizens and as patriotic Americans to read diverse political perspectives. Be a good citizen and read a different perspective today.”

The pilot test results suggested that the injunctive norm had potential. Eighty-two percent of the 103 respondents who evaluated this statement had favorable reactions. Sixteen percent offered some counter-argument or criticism of the statement. As an example of how respondents felt about this prompt, one wrote, “This is a good perspective to have. By looking at different sides, we can better learn why we support the position that we do.”

Based on the largely favorable responses, we proceeded with the experiment for the injunctive norm prompt.

Lab Test

For the lab test, we shortened the injunctive norm slightly so that it would be simpler for a news organization to include prior to a list of hyperlinks:

INJUNCTIVE NORM LAB TEST PROMPT: “Promote a better democracy, read different viewpoints.”

Time and Clicks

The injunctive norm condition did produce some changes in looking at counter-attitudinal views, but only among women.57 Women in the injunctive norm condition were more likely to look at counter-attitudinal views and to spend time with them compared to the control site. No such changes occurred for men.

Emotions and Credibility

There were no differences in perceptions of the credibility of the website or emotional responses to the site when comparing the responses of those viewing the website with the injunctive norm prompt and those viewing the control website that did not contain a prompt.

Health Care Attitudes

Similarly, the injunctive norm prompt did not yield any different attitudes about the health care legislation compared to the control.

Legitimacy

Respondent sex again emerged as an important factor in the effects of the injunctive norm prompt on the perceived legitimacy of one’s own views and the views of others. Women in the injunctive norm condition rated the legitimacy of their views, on average, 1.81 points higher than they rated the legitimacy of the other side’s views.58 Women in the control condition rated them only 1.26 higher. In other words, women in the injunctive norm condition see their views as more legitimate than the opposition and do so more than women in the control condition. The differences for men are not statistically meaningful.

Norms

Yet again for norms, respondent sex conditioned the effect. Men in the injunctive norm condition endorsed beliefs about keeping up with the news and diverse views more than men in the control condition; no differences appeared for women.59

Conclusion

The objectives of this research were twofold. First, we wanted to find prompts with democratic benefits, such as encouraging more time with hard news versus entertainment and bridging political divides in news consumption and interpretation. Second, our hope was to find prompts that had business benefits by increasing the number of page views or improving perceptions of a site’s credibility. The theoretical basis of this research held great promise: studies in psychology, political science, and communication had uncovered evidence that norms, emotions, accountability, accuracy, and self-affirmation could affect people’s political behavior and perceptions.

Some of the findings uncovered here could be read as confirming the results of prior research. How- ever, not all findings lead to clear recommendations. The accuracy prompt did promote more balanced consideration of one’s view vis-à-vis the opposition, yet it had no business implications. The anxiety prompt did encourage some respondents to click more. At the same time, some respondents spent less time with counter-attitudinal articles. Self-affirmation did make people feel more proud and hopeful and led them to spend less time with entertainment. Affirmed respondents also thought more of their own views, however, reporting stronger attitudes and awarding the arguments of their own perspective even more legitimacy than the views of the opposition. And the social norms prompt did increase agreement with news norms for some participants, but left some participants convinced of the greater validity of their own views.

What happened here? Why did we not find a prompt that would encourage respectful engagement with alternative views? Three possibilities present themselves; each is reviewed in turn.

Possibility 1: Prompts were misguided.

Based on a careful review of the research, we tried to create prompts that drew from prior work and, at the same time, were short enough that a news station could reasonably include them on a website. In crafting our prompts, we went through numerous iterations and brainstormed extensively on how to make prompts that were clear, short, and consistent with the research literature. Despite our best efforts, we may have missed the boat and created prompts that simply did not work. We are skeptical, however, that the design of the prompts is the main explanation for our mixed results. We say this for several reasons. First, our pilot testing of the phrases did not produce any indication that respondents were confused about the meaning of the prompts.

Second, the results were mixed both for those prompts where we drastically changed the wording from prior literature and for those prompts where we stayed true to previous work. Our efforts at creating a prompt for accountability and anxiety, for instance, involved notable departures from previous work. In other cases, such as accuracy, however, we were able to draw considerably on previous literature in crafting the wording of the prompt. Regardless of our fidelity to prior work, no prompt produced results that were in line with both democratic and business goals. Yet the prompts did have effects – not all effects were necessarily desirable, however.

Third, there are indications that the prompts worked as expected throughout the findings. Self- affirmation increased hope and pride. The injunctive norms and anxiety prompts increased endorsement of the normative statements, at least among some subgroups. And for some respondents, the accuracy prompt related to legitimacy ratings. Although we encourage testing of additional prompts, we suspect that other phrases will run afoul of some of the same mixed results we uncovered here.

Possibility 2: Article topic affected the results.

In this study, participants first encountered a pro-attitudinal article about health care. If they were opposed to the health care legislation, they saw an article discussing problems with the legislation. If they favored the legislation, the article touted the benefits of the law. We strategically chose health care as the topic of the initial article for several reasons detailed more extensively in the appendix, such as the partisan controversy about the issue. One may worry that the prompts did not work as planned for the health care issue, but that the prompts may have worked had we chosen another issue at the outset. The current research design cannot rule out that possibility. And previous work looking at cues did find differences in how people reacted to a prompt based on the article topic.60 What we can note is that to the extent that it is true that the effects of the prompts vary based on the issue, the effects are even more complicated than documented here. This would mean that newsrooms would have to be extremely cautious in using the prompts based on the web page’s subject. This would only confirm our assertion that prompts have complex effects.

Possibility 3: Context and objective produce unique results.

Another possibility, and the one we find most compelling, is that the context used in this study – prompts encountered while browsing a news site – is distinct. Although some prior research did look at news content, few studies examined the effects of prompts in the context of browsing a news web- site. Further, we analyzed both democratic and business outcomes, a combination that has not been the subject of previous research.

In some ways, it is disheartening not to have a prompt to recommend to newsrooms that will provide democratic and commercial benefits to a general audience. But knowing that reactions to these prompts are finicky is valuable. All of the prompts considered here produced complex results. Newsrooms should carefully consider their objectives and then test any proposed hyperlink prompt to make sure that it has the desired effect.

Please view the full report to see the appendix and more information about the study.

SUGGESTED CITATION:

Stroud, Natalie Jomini, Muddiman, Ashley, and Scacco, Joshua. (2013, September). Hyperlinks. Center for Media Engagement. https://mediaengagement.org/research/hyperlinks/

- Tremayne, M. (2004). The web of context: Applying network theory to the use of hyperlinks in journalism on the web. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 81, 237-253. [↩]

- Chang, T., Southwell, B. G., Lee, H., & Hong, Y. (2011). Jurisdictional protectionism in online news: American journalists and their perceptions of hyperlinks. New Media & Society, 14, 684-700. [↩]

- Chan-Olmsted, S. M., & Suk Park, J. S. (2000). From on-air to online world: Examining the content and structures of broadcast TV stations’ web sites. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 77, 321-339; Dimitrova, D. V., Connolly-Ahern, C., Williams, A. P., Kaid, L. L. & Reid, A. (2003). Hyperlinking as gatekeeping: Online newspaper coverage of the execution of an American terrorist. Journalism Studies, 4, 401-414; Schultz, T. (1999). Interactive options in online journalism: A content analysis of 100 U.S. newspapers. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 5(1). doi: 10.1111/j.1083- 6101.1999.tb00331.x. [↩]

- Dimitrova et al., 2003. [↩]

- Carpenter, S. (2010). A study of content diversity in online citizen journalism and online newspaper articles. New Media & Society, 12, 1064-1084. Tremayne, 2004. [↩]

- Stroud, N. J., Muddiman, A., & Scacco, J. (in press). Engaging audiences via online news sites. In H. Gil de Zúñiga (Ed.), New agendas in communication: New technologies and civic engagement. New York, NY: Routledge. [↩]

- Ketterer, S. (2011). Links engage readers of online crime stories. Newspaper Research Journal, 22(2), 2-13. [↩]

- Hindman, M. (forthcoming). Personalization and the future of news. In H. Gilde Zúñiga (Ed.), New agendas in communication: New technologies and civic engagement. New York, NY: Routledge. [↩]

- Tremayne, M. (2008). Manipulating interactivity with thematically hyperlinked news texts: A media learning experiment. New Media & Society, 10, 703-727. [↩]

- Eveland, W. P., Cortese, J., Park, H., & Dunwoody, S. (2004). How web site organization influences free recall, factual knowledge, and knowledge structure density. Human Communication Research, 30, 208-233; Eveland, W. P., Marton, K., & Seo, M. (2004). Moving beyond ‘just the facts’: The influence of online news on the content and structure of public affairs knowledge. Communication Research, 31, 82–108. [↩]

- Eveland, Marton, & Seo, 2004. [↩]

- Chung, C. J., Nam, Y., & Stefanone, M. A. (2012). Exploring online news credibility: The relative influence of traditional and technological factors. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 17, 171-186. [↩]

- Boczkowski, P. J. & Peer, L. (2011). The choice gap: The divergent online news preferences of journalists and consumers. Journal of Communication, 61, 857-876. [↩]

- Knobloch-Westerwick, S., Sharma, N., Hansen, D. L., & Alter, S. (2005). Impact of popularity indications on readers’ selective exposure to online news. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 49, 296-313. [↩]

- Iyengar, S. & Hahn, K. S. (2009). Red media, blue media: Evidence of ideological selectivity in media use. Journal of Communication, 59, 19-39; Knobloch-Westerwick, S., & Meng, J. (2009). Looking the other way: Selective exposure to attitude-consistent and counter-attitudinal political information. Communication Research, 36, 426-448; Stroud, N. J. (2008). Media use and political predispositions: Revisiting the concept of selective exposure. Political Behavior, 30, 341-366; Stroud, N. J. (2011). Niche news: The politics of news choice. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [↩]

- Garrett, R. K. (2009a). Echo chambers online? Politically motivated selective exposure among Internet users. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 14, 265-285; Garrett, R. K. (2009). Politically motivated reinforcement seeking: Reframing the selective exposure debate. Journal of Communication, 59, 676-699; Holbert, R. L., Hmielowski, J. D., & Weeks, B. E. (2012). Clarifying relations between ideology and ideologically-oriented cable TV news consumption: A case of suppression. Communication Research, 39, 194-216. Knobloch-Westerwick & Meng, 2009. [↩]

- Meffert, M. F., Chung, S., Joiner, A. J., Waks, L., & Garst, J. (2006). The effects of negativity and motivated information processing during a political campaign. Journal of Communication, 56, 27-51; Taber, C. S., & Lodge, M. (2006). Motivated skepticism in the evaluation of political beliefs. American Journal of Political Science, 50, 755-769. [↩]

- Manosevitch, E. (2009). The reflective cue: Prompting citizens for greater consideration of reasons. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 21, 187-203. [↩]

- Binning, K. R., Sherman, D. K., Cohen, G. L., & Heitland, K. (2010). Seeing the other side: Reducing political partisanship via self-affirmation in the 2008 presidential election. Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy, 10, 276-292; Cohen, G. L., Sherman, D. K., Bastardi, A., Hsu, L., McGoey, M., & Ross, L. (2007). Bridging the partisan divide: Self-affirmation reduces ideological closed-mindedness and inflexibility in negotiation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 93, 415-430; Nyhan, B., & Reifler, J. (2011, September 20). Opening the political mind? The effects of self-affirmation and graphical information on factual misperceptions. Unpublished manuscript. Available online at: http://www.dartmouth.edu/~nyhan/opening-political-mind.pdf; Steele, C. M., & Liu, T. J. (1983). Dissonance processes as self-affirmation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 45, 5-19. [↩]

- Cialdini, R. B. (2003). Crafting normative messages to protect the environment. Current Directions in Political Science, 12, 105-109; Cialdini, R. B., Demaine, L. J., Sagarin, B. J., Barrett, D. W., Rhoads, K., & Winter, P. L. (2006). Managing social norms for persuasive impact. Social Influence, 1, 3-15; Gerber, A. S., Green, D. P., & Larimer, C. W. (2008). Social pressure and voter turnout: Evidence from a large- scale field experiment. American Political Science Review, 102, 33–48; Gerber, A. S., Green, D. P., & Larimer, C. W. (2010). An experiment testing the relative effectiveness of encouraging voter participation by inducing feelings of pride or shame. Political Behavior, 32, 409–422; Kam, C. D. (2007). When duty calls, do citizens answer? Journal of Politics, 69, 17-29; Michelson, M. R. (2003). Getting out the Latino vote: How door-to-door canvassing influences voter turnout in rural central California. Political Behavior, 25, 247–263; Schultz, P. W., Nolan, J. M., Cialdini, R. B., Goldstein, N. J., & Griskevicius, V. (2007). The constructive, destructive, and reconstructive power of social norms. Psychological Science, 18, 429-434. [↩]

- Arkes, H. R. (1991). Costs and benefits of judgment errors: Implications for debiasing. Psychological Bulletin, 110, 486-498; Kim, Y. M. (2007). How intrinsic and extrinsic motivations interact in selectivity: Investigating the moderating effects of situational information processing goals in issue publics’ web behavior. Communication Research, 34, 185-211; Kunda, Z. (1990). The case for motivated reasoning. Psychological Bulletin, 108, 480-498; Quinn, A., & Schlenker, B. R. (2002). Can accountability produce independence? Goals as determinants of the impact of accountability on conformity. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28, 472-483. [↩]

- Chen, S., Schechter, D., & Chaiken, S. (1996). Getting at the truth or getting along: Accuracy- versus impression-motivated heuristic and systematic processing. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71, 262-275; Lerner, J. S., & Tetlock, P. E. (1999). Accounting for the effects of accountability. Psychological Bulletin, 125, 255-275; Lundgren, S. R., & Prislin, R. (1998). Motivated cognitive processing and attitude change. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 24, 715-726; Tetlock, P. E. (1983). Accountability and complexity of thought. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 45, 74-83; Tetlock, P. E. (1985). Accountability: The neglected social context of judgment and choice. Organizational Behavior, 7, 297-332; Tetlock, P. E., Skitka, L., & Boettger, R. (1989). Social and cognitive strategies for coping with accountability: Conformity, complexity, and bolstering. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57, 632-640; Thompson, L. (1995). “They saw a negotiation:” Partisanship and involvement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 68, 839-853. [↩]

- Cialdini, 2003; Cialdini, et al., 2006; Gerber, A. S., & Rogers, T. (2009). Descriptive social norms and motivation to vote: Everybody’s voting and so should you. The Journal of Politics, 71, 178–191. [↩]

- MacKuen, M., Wolak, J., Keele, L., & Marcus, G.E. (2010. Civic engagements: Resolute partisanship or reflective deliberation. American Journal of Political Science, 54, 440-458; redlawsk, D.P., Civetini, A.J.W., & Emmerson, K.M. (2010). The affective tipping point: Do motivated reasoners ever “get it”? Political Psychology, 31, 563-593. Valentino, N.A., Hutchings, V.L., Banks, A.J., & Davis, A.K. (2008). Is a worried citizen a good citizen? Emotions, political information seeking, and learning via the internet. Political Psychology, 29, 247-273. [↩]

- Witte, K. (1992). Putting the fear back into fear appeals: The extended parallel process model. Communication Monographs, 59, 329-349; Witte, K. (1994). Fear control and danger control: A test of the extended parallel processing model (EPPM). Communication Monographs, 61, 113-134. [↩]

- Lerner & Tetlock, 1999. [↩]

- Tetlock, 1983, p. 81; see also: Simonson & Nye, 1992; Tetlock & Kim, 1987; Tetlock et al., 1989. [↩]

- Simonson, I., & Nye, P. (1992). The effect of accountability on susceptibility to decision errors. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 51, 416-446; Tetlock, 1983; Tetlock, P. E., & Kim, J. I. (1987). Accountability and judgment processes in a personality prediction task. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52, 700-709; Tetlock et al., 1989; Thompson, E. P., Roman, R. J., Moskowitz, G. B., Chaiken, S., & Bargh, J. A. (1994). Accuracy motivation attenuates covert priming: The systematic reprocessing of social information. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 66, 474-489. [↩]

- Tetlock, 1983, p. 76. [↩]

- Arkes, 1991; Kunda, 1990. [↩]

- Kim, 2007. [↩]

- The interaction between condition (control vs. accuracy) and sex (male vs. female) was significant in an ANCOVA controlling for age, education, income, race/ethnicity, political knowledge, partisanship, ideology, opinion on the legislation, and strength of partisanship (F(1, 244)=3.98, p<.05). [↩]

- The interaction between condition (control vs. accuracy) and attitudes toward the legislation (favor vs. oppose) was significant in an ANCOVA controlling for the previously noted covariates (F(1, 209)=6.98, p<.01). [↩]

- The interaction between condition (control vs. accuracy) and attitudes toward the legislation (favor vs. oppose) was significant in an ANCOVA controlling for the previously noted covariates (F(1, 244)=4.89, p<.05). [↩]

- MacKuen et al., 2010. Redlawsk et al., 2010. Valentino et al., 2008. MacKuen, M., Wolak, J., Keele, L., & Marcus, G. E. (2010). Civic engagements: Resolute partisanship or reflective deliberation. American Journal of Political Science, 54, 440-458; Redlawsk, D. P., Civettini, A. J. W., & Emmerson, K. M. (2010). The affective tipping point: Do motivated reasoners ever “get it”? Political Psychology, 31, 563–593; Valentino, N. A., Hutchings, V. L., Banks, A. J., & Davis, A. K. (2008). Is a worried citizen a good citizen? Emotions, political information seeking, and learning via the internet. Political Psychology, 29, 247–273. [↩]

- Valentino et al., 2008, p. 255. [↩]

- Witte, 1992; 1994. [↩]

- The interaction between condition (control vs. anxiety) and strength of partisanship was significant in an ANCOVA controlling for the previously noted covariates (F(1,240)=4.69, p<.05). The result continues to hold if a dichotomized variable indicating whether or not a respondent clicked on a counter-attitudinal article is used (as opposed to the ratio-level variable employed in the figure). [↩]

- The interaction between condition (control vs. anxiety) and strength of partisanship was significant in an ANCOVA controlling for the previously noted covariates (F(1,240)=4.12, p<.05). [↩]

- The interaction between condition (control vs. anxiety) and sex (male vs. female) was significant in an ANCOVA controlling for the previously noted covariates (F(1,240)=5.63, p<.05). [↩]

- The interaction between condition (control vs. anxiety) and political knowledge was significant in an ANCOVA controlling for the previously noted covariates (F(1,240)=3.91, p<.05). The political knowledge measure was split at the median for the purposes of the graph. [↩]

- The interaction between condition (control vs. anxiety) and sex (male vs. female) was significant in an ANCOVA controlling for the previously noted covariates (F(1,240)=10.26, p<.01). [↩]

- The interaction between condition (control vs. anxiety) and political knowledge was significant in an ANCOVA controlling for the previously noted covariates (F(1,240)= 11.75, p<.01). The political knowledge measure was split at the median for the purposes of the graph. [↩]

- Steele, C. M., & Liu, T. J. (1983). Dissonance processes as self-affirmation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 45, 5-19. [↩]

- Cohen, G. L., Sherman, D. K., Bastardi, A., Hsu, L., McGoey, M., & Ross, L. (2007). Bridging the partisan divide: Self-affirmation reduces ideological closed-mindedness and inflexibility in negotiation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 93, 415-430. [↩]

- Sherman, D. K., Cohen, G. L., Nelson, L. D., Nussbaum, A. D., Bunyan, D. P., & Garcia, J. (2009). Affirmed yet unaware: Exploring the role of awareness in the process of self-affirmation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 97, 745-764. [↩]

- See review of different approaches by McQueen, A., & Klein, W. M. P. (2006). Experimental manipulations of self-affirmation: A systematic review. Self and Identity, 5, 289-354. [↩]

- Condition (control vs. self-affirmation) was significant in an ANCOVA controlling for the previously noted covariates (F(1,243)=4.39, p<.05). The same relationship holds for a dichotomized version of whether or not one viewed entertainment (M=.13 for self-affirmation, M=.24 for control, F(1, 243)=4.45, p<.05). [↩]

- The interaction between condition (control vs. self-affirmation) and strength of partisanship was significant in an ANCOVA controlling for the previously noted covariates F(1, 242)=4.70, p<.05. Testing the relationship with time with a dichotomized counter-attitudinal views variable (either did or did not click on a counter-attitudinal article) does not produce a significant interaction between condition (control vs. self-affirmation) and strength of partisanship, controlling again for the same battery of covariates F(1, 242)=2.43, p=.12. [↩]

- Condition (control vs. self-affirmation) was significant in an ANCOVA controlling for the previously noted covariates (F(1,243)=4.81, p<.05). [↩]

- Condition (control vs. self-affirmation) was significant in an ANCOVA controlling for the previously noted covariates (F(1,243)=3.04, p<.05, one-tailed). [↩]

- Condition (control vs. self-affirmation) was significant in an ANCOVA controlling for the previously noted covariates (F(1,243)=3.52, p<.05, one-tailed). [↩]

- The interaction between condition (control vs. self-affirmation) and sex (male vs. female) was significant in an ANCOVA controlling for the previously noted covariates (F(1,242)=5.81, p<.05). [↩]

- Condition (control vs. self-affirmation) was significant in an ANCOVA controlling for the previously noted covariates (F(1,243)=5.97, p<.05) [↩]

- Condition (control vs. self-affirmation) was significant in an ANCOVA controlling for the previously noted covariates (F(1,203)=3.07, p<.05, one-tailed). [↩]

- Smith, A. (2011, March 17). The Internet and campaign 2010. Pew Internet & American Life Project. [↩]

- The interaction between condition (control vs. injunctive norm) and sex (male vs. female) was marginally significant in an ANCOVA controlling for the previously noted covariates (F(1,239)=3.54, p<.10). Testing the relationship with time with a dichotomized counter-attitudinal views variable (either did or did not click on a counter-attitudinal article) does produce a significant interaction between condition (control vs. anxiety) and strength of partisanship, controlling again for the same battery of covariates F(1, 239)=6.67, p<.05. Here, on average, 58.0 percent of women clicked on the counter-attitudinal article in the injunctive norm condition and only 37.7 percent did so in the control, a significant difference (p<.05); 26.8 percent of men clicked on a counter-attitudinal article in the injunctive condition and 38.8 percent did so in the control, a non-significant difference. [↩]

- The interaction between condition (control vs. injunctive norm) and sex (male vs. female) was significant in an ANCOVA controlling for the previously noted covariates (F(1,199)=5.14, p<.05). [↩]

- The interaction between condition (control vs. injunctive norm) and sex (male vs. female) was significant in an ANCOVA controlling for the previously noted covariates (F(1,239)=5.74, p<.05). [↩]

- Manosevitch, 2009. [↩]