In October 2019, CNN declined to air two 30-second paid advertisements from President Donald Trump’s re-election campaign. The two advertisements, titled “Biden Corruption” and “Coup,” came in the aftermath of Nancy Pelosi, Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives, announcing the launch of a formal impeachment inquiry against Trump.

The inquiry was the result of revelations of a reported phone call President Donald Trump had with Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky in July 2019 in which Trump insinuated the Ukranian government should investigate former Vice President Joe Biden and his son Hunter Biden. Hunter Biden worked for a Ukranian energy company whose owner was being investigated by Ukranian prosecutor general Viktor Shokin (Vogel, 2019). In 2016, Shokin was ousted as prosecutor general in light of accusations of corruption (Kramer, 2016). Trump and his supporters argue that Biden used his power as vice president to protect his son’s employer and influence the dismissal of Shokin. The New York Times reports, however, that “no evidence has surfaced that the former vice president intentionally tried to help his son by pressing for the prosecutor’s dismissal” (Vogel, 2019).

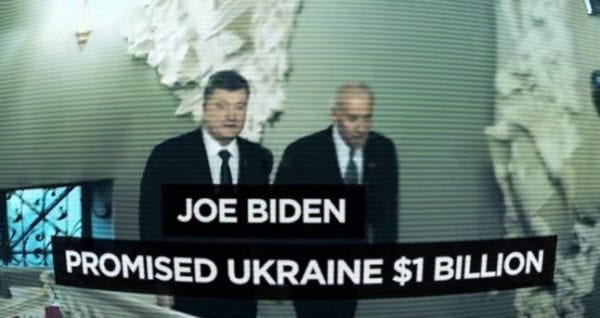

It was revealed that days before Trump and Zelensky’s July 2019 phone call that Trump directed his chief of staff “to place a hold on about $400 million in military aid for Ukraine,” (Pryzbyla & Edelman, 2019), leading some to believe the president issued a quid pro quo in order to tarnish a political rival. The pro-Trump advertisements that CNN refused to air attack network journalists such as Don Lemon and Chris Cuomo, calling them “media lapdogs,” label the House impeachment inquiry as a “coup,” and accuse Joe Biden of promising $1 billion to the Ukraine if Shokin was ousted (Grynbaum, 2019). CNN rejected the advertisements on the grounds they “contained inaccuracies and unfairly attacked the network’s journalists” and stated one ad in particular made “assertions that have been proven demonstrably false” (Grynbaum & Hsu, 2019).

Despite partisan pushback, the network’s move is not an unusual one. Unlike broadcast channels such as NBC, CBS, and ABC, cable networks are not obliged to follow regulations from the Federal Communications Commission pertaining to political advertisements. Because cable networks do not broadcast over “public” airwaves (Tompkins, 2019), they have more power to choose what political advertisements they showcase. Alternatively, broadcast channels are required “to air ads that come from legally qualified political candidates, according to the FCC” (Vranica & Horwitz, 2019), even if they may be laden with what the channel might consider spin, inaccuracies, and fabrications.

CNN wasn’t the only network that decided not to air the two Trump advertisements. NBCUniversal made the decision to pull the “Biden Corruption” ad after it aired once on the company’s cable network channels MSNBC and Bravo (Vranica & Horwitz, 2019). The controversy over these advertisements leads many to ask the question: Should national cable news networks have the power to pick and choose the political advertisements their viewers are exposed to? For those who agree that news networks should have the capability to reject political ads, an argument could be that rejecting ads with false information protects voters from believing and spreading misinformation. Despite the rise of social media, television has remained the main source of election news for a majority of people in the United States. A Pew Research survey found that during the 2016 presidential election, 24% of respondents said they learned information about the presidential election through cable news, followed by 14% receiving information from social media and local television (Gottfired et al., 2019). CNN’s decision could be seen as a way to protect the public from an ad that entangles political persuasion and unconfirmed accusations.

Those opposing CNN’s decision boiled down to two points: partisanship and free speech. Trump has been known to denounce CNN on multiple occasions labeling them as the “fake news media,” and accusing them of partisan bias in favor of Democrats (Samuels, 2019). Tim Murtaugh, communications director for the Trump campaign, argued that the campaign’s “Biden corruption” ad was “entirely accurate and was reviewed by counsel” and that CNN was “protecting Joe Biden in their programming” (Grynbaum & Hsu, 2019). The notion that CNN’s rejection is a partisan ploy also connects to the fear of a suppression of political speech. Facebook’s decision to allow the “Biden Corruption” ad on its social media platform was based on a “fundamental belief in free expression, respect for the democratic process, and the belief that, in mature democracies with a free press, political speech is already arguably the most scrutinized speech there is” (Lima, 2019). Those supporting enabling access to this advertisement seem concerned that when political advertisements are censored and viewers are not equitably presented with arguments across multiple media platforms, democracy consequently suffers.

As the 2020 presidential election increasingly dominates news media, more controversial advertisements are likely to be released to the public for mass consumption on radio, print, social media, and television. Some might perceive an advertisement as well-argued and appropriately passionate, whereas others might accuse the same message of containing spin, emotional manipulation, or downright falsehoods. Outlets like CNN will continue to be faced with a choice: should they allow any kind of political advertisements on their channel —and leave conclusions and judgments of their veracity to viewers— or should they reject advertisements they believe contain some amount of misinformation in an effort to shield viewers’ political opinions from what they judge as abuse? How much power should a cable network wield in influencing, directly or indirectly, their audience’s exposure to a candidate’s message?

Discussion Questions:

- What are the ethical implications of CNN rejecting to air Trump’s two advertisements on its network? What values are in conflict?

- How could CNN have alternatively handled the situation other than rejecting to air the advertisements?

- Facebook said its decision to keep Trump’s two advertisements on its platform was based on the “belief in free expression” and “respect for the democratic process.” In what ways, if any, did CNN’s decision corroborate or contradict these beliefs?

- How does partisanship play a role in this scenario? Does partisanship affect the ways audience members consume media?

- Should news outlets be in the habit of fact-checking advertisements before they accept them? What is workable or problematic about this proposal?

Further Information:

Gottfried, J., Barthel, M., Shearer, E., and Mitchell, A. “The 2016 Presidential Campaign – a News Event That’s Hard to Miss.” Pew Research Center, February 4, 2016. Available at: https://www.journalism.org/2016/02/04/the-2016-presidential-campaign-a-news-event-thats-hard-to-miss/

Grynbaum, M. & Hsu, T. “CNN Rejects 2 Trump Campaign Ads, Citing Inaccuracies.” The New York Times, Oct. 3, 2019. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/10/03/business/media/cnn-trump-campaign-ad.html

Kramer, A. “Ukraine Ousts Viktor Shokin, Top Prosecutor, and Political Stability Hangs in the Balance.” The New York Times, March, 29, 2016. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2016/03/30/world/europe/political-stability-in-the-balance-as-ukraine-ousts-top-prosecutor.html

Lima, C. “How Trump is winning the fight on ‘baseless’ ads.” POLITICO, Oct. 11, 2019. Available at: https://www.politico.com/news/2019/10/11/trump-joe-biden-ad-social-media-misinformation-044267

Przybyla, H. & Edelman, A. “Nancy Pelosi announces formal impeachment inquiry of Trump.” NBC News, September 24, 2019. Available at: https://www.nbcnews.com/politics/trump-impeachment-inquiry/pelosi-announce-formal-impeachment-inquiry-trump-n1058251

Samuels, B. “Trump campaign threatens to sue CNN, citing Project Veritas videos.” The Hill, October 18, 2019. Available at: https://thehill.com/homenews/campaign/466473-trump-campaign-threatens-to-sue-cnn-citing-project-veritas-videos

Tompkins, A. “Do the networks have to give equal time? In a word, no.” Poynter, January 8, 2019. Available at: https://www.poynter.org/ethics-trust/2019/do-the-networks-have-to-give-equal-time-in-a-word-no/

Vogel, K. “Trump, Biden and Ukraine: Sorting Out the Accusations.” The New York Times, September 22, 2019. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/09/22/us/politics/biden-ukraine-trump.html

Vranica, S. & Horwitz, J. “NBCU Cable Networks Refuse to Air Trump Campaign Ad Aimed at Joe Biden.” The Wall Street Journal, Oct. 10, 2019. Available at: https://www.wsj.com/articles/nbcu-refuses-to-air-trump-campaign-ad-aimed-at-joe-biden-11570746377

Authors:

Allyson Waller & Scott R. Stroud, Ph.D.

Media Ethics Initiative

Center for Media Engagement

University of Texas at Austin

February 3, 2020

Image: Youtube.com / modified

This case study is supported by funding from the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. It can be used in unmodified PDF form for classroom or educational settings. For use in publications such as textbooks, readers, and other works, please contact the Center for Media Engagement.

Ethics Case Study © 2020 by Center for Media Engagement is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0