SUMMARY

Anonymity has become an increasingly common aspect of everyday society, appearing in the form of anonymous leaks and unnamed media sources, anonymous chat rooms, undisclosed political donors, and even groups like “QAnon” and “Anonymous.” Use of anonymous communication can be controversial amid tensions between the desire to hold people accountable for their communicative behaviors and the desire to protect people from unjust retaliation when they do speak.

Despite the prevalence of these tensions, we have very little data substantiating and exploring the challenges of anonymity on a wide-scale basis. The Center for Media Engagement sought to better understand how certain socio-political differences — including where people get their news, time spent online, political views, and age — relate to people’s views about anonymity. We found that:

- People’s attitudes about anonymity vary widely, but tend to be more positive.

- People’s attitudes about anonymous communication relate to the types of news sources they use.

- The number of news sources people use relates to their views on anonymous communication. Specifically, when people rely on a greater variety of news outlets, they are more likely to have stronger attitudes toward anonymity (both positive and negative).

- People who spend more time online have stronger and generally more positive views about anonymous communication.

- Millennials report more overall positive attitudes about anonymous communication compared to most other age groups.

- People with highly conservative political views have somewhat more negative views of anonymity compared to slightly conservative or moderate individuals.

BACKGROUND

Anonymity is commonly viewed on a continuum (allowing for partial anonymity) and is usefully seen as a perception of the communicators involved. Those perceptions of anonymity can vary sometimes dramatically.

Anonymity can be linked to potential power and status differentials and is sometimes used to overcome such differences. On the one hand, anonymity can be seen as having the potential to be quite valuable — promoting open and honest communication and free speech, protecting people from unjust retaliation, and promoting risk-taking and innovation. It can help provide voice to those who might otherwise be reluctant to speak. On the other hand, its use can be very destructive — facilitating criminal or questionable acts, reducing accountability for harmful communication and other behaviors, and avoiding disclosure of certain information.1 Interestingly, it is even possible to hold a view that anonymity is both constructive and destructive.

These variations are reflected in attitude assessments of the appropriateness of various forms of anonymity. The current polarized political climate in the U.S. suggests several differences across the population that may lead to varied attitudes about anonymity. For example, where people get their news and how well informed they are overall may influence attitudes toward anonymity. Age may also matter given generational differences and expectations, as well as time spent online, considering that anonymity is commonly linked to mediated environments. Of even greater interest is how political views reflecting beliefs about personal accountability, rights and freedoms, and protection of the marginalized may lead to variations in views about the role anonymity plays in our society.

To examine links between these socio-political factors and different attitudes towards anonymous communication, the Center for Media Engagement analyzed responses gathered in late fall 2019 from a sizable survey questionnaire.

KEY FINDINGS

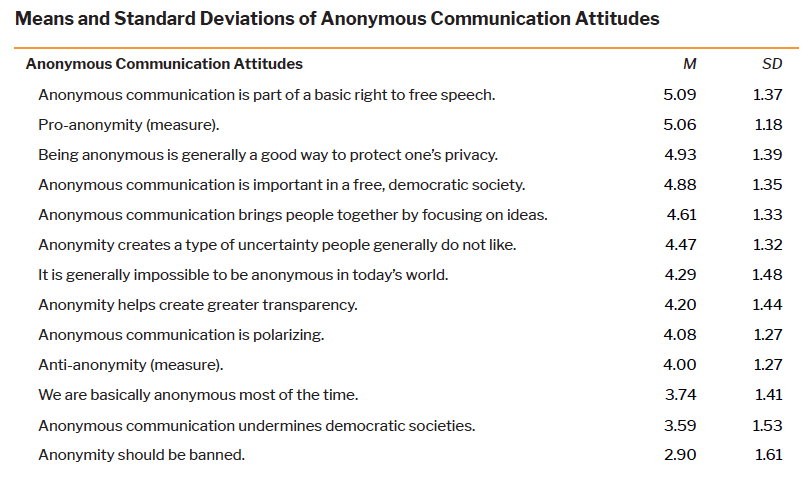

Overall, people have diverse opinions about anonymity in our society, though they are generally more positive than negative.2

- People clearly agree that anonymous communication is part of a basic right to free speech and is important in a free democratic society.

- People tend to view anonymity as a good way to protect privacy, and think that anonymous communication brings people together by focusing on ideas.

- People generally disagree that anonymity undermines democratic societies and that it should be banned.

A richer engagement with a variety of news sources tends to relate to people’s stronger opinions, both positive and negative, about anonymity.

- Consumers of multiple news sources tend to hold positive views about anonymity and see it as creating greater transparency and protecting one’s Individuals who use more news sources also tend to see anonymous communication as part of a basic right to free speech and as playing an important role in a free, democratic society.

- The more news sources people rely on, the more likely they also believe anonymous communication to be polarizing and something that creates unwanted uncertainty.

- People who do not use Internet news sources are more likely to have more singularly negative views of anonymity — including the beliefs that anonymity should be banned and that we are generally anonymous most of the time — than those who do consume online news.

Findings for time spent online and for generation show some parallels.

- Those who spend more time online are more likely to have pro-anonymity views and to believe anonymity protects privacy and promotes transparency.

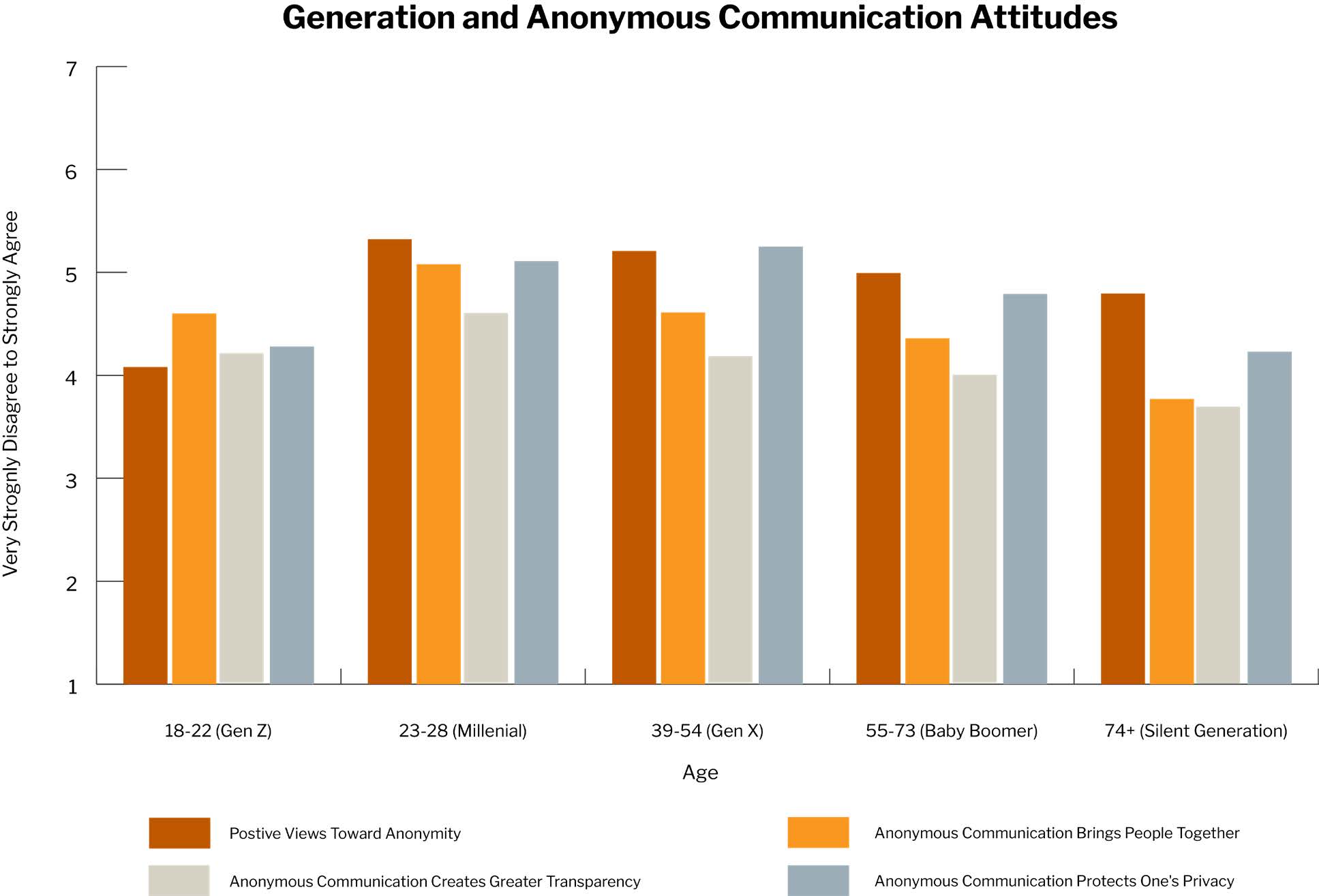

- Millennials tend to have stronger beliefs about anonymity bringing people together and promoting transparency than baby boomers and individuals from the silent generation. People in the Gen X cohort tend to have stronger views about anonymity protecting privacy than those considered Gen Z. Both millennials and Gen X individuals comprise adults who generally spend more time in a wide variety of online settings.

There are relatively few differences in how people view anonymous communication based on political views, although there are differences for some of the more extreme attitudes.

- Highly conservative individuals are more likely than those with moderate political views to believe anonymity should be banned.

- Highly conservative individuals are more likely than slightly conservative or moderate individuals to hold anti-anonymity views overall.

IMPLICATIONS

Overall, we consistently found that heavier news engagement, generation (i.e., millennials), and greater time spent online are all linked to stronger pro-anonymity views as well as beliefs that anonymity creates greater transparency. Journalists, political leaders, and other decision makers may be able to use our results as they incorporate forms of anonymity (such as unnamed sources, anonymous suggestions, and unidentified leaks) in their work with various stakeholder groups:

- Our findings emphasizing positive attitudes for anonymous communication run somewhat counter to conventional wisdom that anonymity is problematic because it reduces accountability.

- As people are exposed to news through multiple sources, they may be more likely to form opinions about the value (or not) of anonymity in our society and experience it as a nuanced form of idea expression.

- Well-informed individuals who spend a sizable amount of time online may view the role of anonymity in creating ideals like transparency differently than other groups.

- Time spent online may include more exposure to some of the anonymity found in parts of the Internet and may thus be linked to more positive views of that anonymity.

- In some cases, older generations, who may have experienced less anonymity, may not as readily see how it could facilitate certain positive goals.

Beyond studying age and length of time spent online, future research should examine relationships between types of online experiences and attitudes about anonymous communication.

FULL FINDINGS

Differences in News Source Preferences and Anonymous Communication Attitudes

People’s attitudes about anonymous communication are related to the types of news sources they use. For instance, individuals who get news from the Internet tend to have stronger pro-anonymity views than those who do not rely on the Internet for news. Individuals who do not use the Internet as a news source are more likely to believe anonymity should be banned and that people are basically anonymous most of the time compared to people who do access news from the Internet. Overall, people are more likely to obtain their news from Internet and television sources compared to other media (e.g., newspaper and radio).

Getting news from most television sources (e.g., local TV news, Fox TV news) does not seem to affect people’s attitudes about anonymous communication. A major exception to that concerns CNN. People who turn to CNN for news report stronger attitudes about anonymous communication in a variety of areas. For example, CNN consumers have stronger overall pro-anonymity views and are more likely to see anonymous communication as serving an important role in a free, democratic society and bringing people together by focusing on ideas. People who get news from CNN are also more likely to view anonymity as helping to create greater transparency and as a good way to protect privacy; they are also more likely to think that communicating anonymously is part of a basic right to free speech. However, CNN viewers also feel more strongly that being anonymous is polarizing and creates a type of uncertainty people ordinarily do not like; additionally, they are more likely to believe that it is generally impossible to be anonymous in today’s world. The only other exception we found to the trend of television sources not impacting people’s views on anonymous communication was that people who do not use other national TV news sources (i.e., sources other than CNN or Fox TV news) are more likely to believe that anonymity should be banned.

People who get their news from local newspapers have stronger pro-anonymity as well as anti-anonymity views compared to individuals who do not use this news source. Local newspaper consumers are also more likely to perceive anonymity as creating a type of uncertainty people generally do not like. This same pattern is also found with consumers of national newspapers. People who read local newspapers are also more likely to view anonymous communication as polarizing, yet also believe that anonymity helps to create greater transparency and that communicating anonymously is part of a basic right to free speech. People who read national newspapers are more likely to believe that people are anonymous most of the time.

Those who get their news from radio talk shows tend to believe anonymity helps to create greater transparency and agree that being anonymous is a good way to protect one’s privacy.

As the number of news sources people use increases, they are more likely to have stronger pro-anonymity views and see anonymous communication as playing an important role in a free, democratic society. They are also more likely to view anonymity as polarizing. Additionally, using more news sources is linked to a greater tendency to believe that anonymity protects privacy and is part of a basic right to free speech. Using more news sources is also associated with perceiving anonymity as helping to create greater transparency while also creating a type of uncertainty people generally do not like. Finally, the greater the number of news sources people consume, the more likely they are to believe it is generally impossible to be anonymous in today’s world.

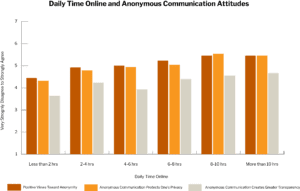

Differences in Time Spent Online and Anonymous Communication Attitudes

People who spend larger amounts of time online have stronger and generally more positive views about anonymous communication. Specifically, people who spend six or more hours a day online have greater pro-anonymity views compared to people who spend fewer than two hours a day online. Individuals who spend eight or more hours a day online are also more likely to believe that being anonymous is generally a good way to protect privacy compared to people who spend fewer than two hours a day online. Finally, people who spend 10 or more hours a day online are more likely to view anonymity as helping to create greater transparency than individuals who spend fewer than two hours a day online.

Differences in Political Views and Anonymous Communication Attitudes

There are relatively few differences in how people view anonymous communication based on their political views. However, individuals who have highly conservative political views report stronger anti-anonymity views compared to slightly conservative individuals or moderate individuals. Highly conservative people also are more likely to believe anonymity should be banned compared to more moderate individuals. Having more liberal political views is not significantly different from other political orientations when it came to attitudes about anonymity.

Generational Differences In Anonymous Communication Attitudes

Millennials tend to report more overall positive attitudes related to anonymous communication compared to other generations. Millennials are more likely than baby boomers to assess being anonymous as helping to create greater transparency. Millennials are also more likely than baby boomers and members of the silent generation to see anonymous communication as bringing people together by focusing on ideas. Notably, Gen X individuals are more likely to view being anonymous as a means to protect privacy compared to people in the Gen Z cohort. People from the millennial, Gen X, and baby boomer cohorts are also each more likely to have pro-anonymity views compared to Gen Z individuals.

METHODOLOGY

A representative sample — based on age, education, gender, race, income, and geographic region — of 617 respondents from across the U.S. was collected through Qualtrics panels, though the data reported here was from one of two subsets that answered more extended questions about anonymity.

Researchers captured sociodemographic measures using the following criteria. Respondents reported their age range, which corresponded with generational cohorts: 18-22 (Gen Z), 23-38 (Millennials), 39-54 (Gen X), 55-73 (Baby Boomers), and 74+ (Silent Generation). People indicated their political views according to one of five options: very liberal, slightly liberal, neither liberal nor conservative (moderate), slightly conservative, and very conservative. Time spent online each day was answered in these categories: rarely if ever online; less than two hours; two to four hours; four to six hours; six to eight hours; eight to ten hours; more than ten hours. We asked about a wide range of news sources (each answered as yes/no): local newspapers, national newspapers, local TV news, CNN TV news, Fox TV news, other national TV news, radio talk shows, other radio news, Internet/online news sources, discussions with friends/family, and other. In addition to looking at individual news sources, we also combined them to look at the total number of news sources utilized.

Before completing the attitude measures for anonymous communication, respondents were told “Anonymous communication concerns the degree to which the identity of a communicator is unknown or invisible. This assessment of anonymity is based on people’s perceptions.” Two general anonymity attitudes, informed by prior research, were created for this study and examined here. Pro-anonymity attitude reflects a positive orientation toward anonymity as a reasonable right that communicators should have. It was measured with three items: “people have a right to communicate anonymously when they want to”; “if someone is communicating anonymously, they must have a good reason for doing so”; and “it is important that people have the option to communicate anonymously.”3 Anti-anonymity reflects a negative orientation toward anonymity as something unacceptable where people are hiding something. It too was measured with three items: “if something is worth saying, it’s worth attaching your name to it”; “if someone is communicating anonymously, they must be hiding more than their name”; and “it is usually unacceptable for people to communicate anonymously.”4 Both scales were assessed on a 7-point Likert-type scale ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree. Factor analysis confirmed these are separate measures and indeed the items are uncorrelated with one another,5 suggesting they measure distinct attitudes toward anonymity. Several more specific attitudes about the appropriateness of anonymity were also assessed with one item on a 7-point Likert-type scale ranging from very strongly disagree to very strongly agree. These items (along with the two scales) are listed in the table below.

Suggested Citation

Scott, C. R. and Schlag, K. E. (August, 2021). How politics, generation, news use, and time online play into attitudes about anonymity. Center for Media Engagement. https://mediaengagement.org/research/how-politics-generation-news-use-and-time-online-play-into-attitudes-about-anonymity

- Bronco (2004). Benefits and drawbacks of anonymous online communication: Legal challenges and communicative recommendations. In S. Drucker (Ed.), Free speech yearbook (vol. 41, pp. 127-141). Washington, DC: National Communication Association. [↩]

- All socio-political differences on attitudes of anonymity described in this study were significant at p < .05. [↩]

- Cronbach’s alpha for the Pro-anonymity measure was a = .80. [↩]

- Cronbach’s alpha for the Anti-anonymity measure was a = .73. [↩]

- Factor analysis confirmed the Pro-anonymity and Anti-anonymity scales were separate measures and uncorrelated with one another (r = -.003). [↩]