As of September, the United States has seen over 170,000 deaths due to the spread of the coronavirus (The COVID Tracking Project, 2020). These figures have shocked many into taking precautionary measures recommended by health experts such as self-quarantine and wearing face coverings in public in an effort to stop the spread of the virus. However, there have also been a number of skeptics who argue that the scale of the pandemic has been exaggerated and the lockdown prolonged for too long (Black, 2020). While these “COVID deniers” may be written off as conspiracy theorists that no one will listen to, in reality some of them are high-profile figures with large platforms – including the President himself. Donald Trump has had a variety of responses to the COVID-19 outbreak as it has progressed, such as referring to the virus as a Democratic party hoax attempting to distract from the November election, accusing hospitals of hoarding medical supplies, and suggesting Americans ingest disinfectant as a treatment (Egan, 2020; Milman, 2020; BBC News, 2020).

Perhaps most concerning is Trump’s disregard for the advice of medical experts and scientists. For example, “Trump and some of his aides have begun questioning whether deaths are being over-counted” while Dr. Anthony Fauci, the director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases as well as the chief medical advisor of the White House Coronavirus Task Force, indicated that “the opposite could be true: that coronavirus deaths are being undercounted as people die at home without going to hospital” (Liptak & Acosta, 2020). Fauci has also suffered “sustained criticism from the President’s allies in conservative media for his willingness to directly refute Trump and counter his more optimistic rhetoric about the pandemic” (LeBlanc, 2020). This has resulted in a number of Trump’s supporters taking to social media and calling to “#FireFauci;” though Trump has not said the same directly, he did passively retweet one of these calls on Twitter (Duster, Acosta, & Liptak, 2020). Similarly, federal immunologist Rick Bright recently filed a whistleblower complaint, arguing that he was ousted from his position as director of the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA) for political reasons after raising concerns about the development of what he claimed a “questionable” coronavirus treatment endorsed by Trump. While the President simply dismissed his case as that of a “disgruntled employee who’s trying to help the Democrats win an election,” Dr. Bright expressed “I am frustrated at a lack of leadership. I am frustrated at a lack of urgency to get a head start on developing life-saving tools for Americans. I’m frustrated at our inability to be heard as scientists” (Segers, 2020).

The President’s resistance to medical expertise presents us with an interesting ethical challenge to consider: Does Trump, or any other political leader, have a social responsibility to affirm the opinions of professionals and specialists? On the one hand, all U.S. citizens (regardless of occupation or leadership status) have a right to their own beliefs and to free speech, including the right to question, challenge, and criticize authority. In fact being skeptical, rather than just accepting information at face-value, is generally considered an important aspect of critical thinking. Furthermore, some may argue that despite their extensive education, experts are not infallible. In fact, there have been plenty of times throughout history when professionals in a variety of fields have been wrong in making predictions. For example, renowned economist Irving Fisher famously declared that “stocks have reached what looks like a permanently high plateau” just three days before Great Depression stock market crash and even various ship-building experts believed the Titanic to be “unsinkable” (Bukszpan, 2011). Even in medicine, there have been times when experts have given unsafe advice. In the 1960’s for instance, some OBGYNs began to recommend thalidomide to alleviate their pregnant patient’s morning sickness, only to later discover that the drug caused severe birth defects (Fintel, Samaras, & Carias, 2009). In this sense, skepticism appears to be a healthy reaction, since too much uncritical trust in anyone might prove dangerous.

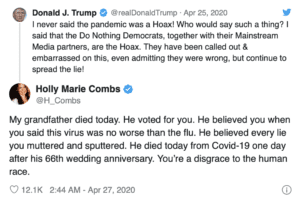

On the other hand, others insist that this is a case where the experts are clearly right and, rather than being merely skeptical, Trump is in denial. Beyond this stance, unlike the recommendation of thalidomide, the coronavirus precautionary advice causes no harm in the case that experts are mistaken. Even if COVID-19 isn’t as serious as experts claim, the argument goes, wearing masks and staying home cannot hurt anyone – isn’t it better to be safe than sorry? Regardless of Trump’s personal beliefs and the legal right to express his doubts, perhaps the larger issue at hand is if doing so is ethical. “COVID acceptors” believe that the powerful have a social responsibility to tread cautiously and defend the recommendation of medical specialists due to the large influence they have over their followers. Unlike ordinary skeptics of COVID who have no platform, the example set by the President matters for those watching his actions and words. A recent study found that republicans “are more likely to view the President’s response to the pandemic more favorably. Holding the view that the virus is not a threat or severe may lead more republicans to engage in unsafe behavior such as congregating in larger groups of people and taking fewer health precautions” (Johnson, Pollock, & Rauhaus, 2020, p. 260). Thus, political leaders must consider the weight of their words and actions as they have a direct impact on those who look up to them. Indeed, it was this exact reasoning that actress Holly Marie Combs held Trump directly responsible for the death of her grandfather, tweeting:

In her tweet, the Charmed star suggests that had the President confirmed the seriousness of the disease and advocated for preventative measures as outlined by health experts, her Trump-supporting grandfather would have taken his advice and might still be alive.

Though Combs’ loss and the many others like it are tragic, it is difficult to place ultimate responsibility for one’s own health on anyone but that individual. Like the age-old question parents ask of their children: If your friend jumped off of a cliff, does that mean you would do it too? In other words, just because we admire someone, doesn’t mean we have to follow their lead. Just as some citizens choose to follow the advice of experts, others may choose otherwise and that is exactly what Comb’s grandfather did – the President did not force him out of his home-based quarantine.

While experts may be “powerful” in the sense that they are recognized authorities of knowledge and their recommendations are taken seriously by their followers, they do not have platforms nearly as large as the President of the United States nor any material power to require, enforce, and aid citizens in isolation efforts – only political authorities have such power. As the COVID-19 pandemic continues, we must consider what obligation political leaders have toward professionals and how much skepticism they should display in attempting to disrupt accepted authorities and narratives. Skepticism of received views, or of views that have traditionally been in the mainstream or held by those in power, has often been seen as a hallmark of critical and independent thinking. But here, Trump’s skepticism might please his supporters while plunging them into great risk: since seniors are not only the most likely to be harmed by COVID-19 but also more likely to vote republican, Trump’s massive influence over this particularly vulnerable population could risk thousands of lives (Johnson, Pollock, & Rauhaus, 2020). Should powerful individuals like Trump err on the side of following the experts of the day or in evincing a certain amount of skepticism about traditional knowledge sources?

Discussion Questions:

- What are the central values at stake in this case?

- What distinguishes healthy skepticism from harmful habits of denial?

- Do you agree or disagree that politicians have a social responsibility to uphold the professional opinions of experts? Why or why not?

- Does anyone with power and a large platform (e.g. celebrities or Instagram influencers) share this responsibility? Why or why not?

- How does the setting of a global pandemic impact your evaluation of Trump’s actions? For example, do you think the powerful should always affirm expertise, regardless of their own beliefs, or do you think such a responsibility is only required in times of crisis?

- How can ordinary citizens strike a balance between trusting expertise and uncritically accepting anything from educated, yet imperfect, people?

- If Trump acted against his own skeptical beliefs and advocated for following medical officials’ advice, would he be lying or acting dishonestly? Why or why not would such a circumstance be considered deceptive or inauthentic?

Further Information:

BBC News. (2020, April 24). Coronavirus: Outcry After Trump Suggests Injecting Disinfectant as Treatment. Available at: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-52407177

Black, C. (2020, May 8). Fear of COVID-19 Is Overblown, It’s Time to Get the Economy Moving Again. National Post, Available at: https://nationalpost.com/opinion/conrad-black-fear-of-covid-19-is-overblown-its-time-to-get-the-economy-moving-again

The COVID Tracking Project. (n.d.). Available at: https://covidtracking.com/

Bukszpan, D. (2014, August 27). 14 Spectacularly Wrong Predictions. CNBC News. Available at: https://www.cnbc.com/2011/05/19/14-spectacularly-wrong-predictions.html

Duster, C., Acosta, J., & Liptak, K. (2020, April 13). Trump Retweets Call to Fire Fauci Amid Coronavirus Criticism. CNN News. Available at: https://www.cnn.com/2020/04/13/politics/donald-trump-anthony-fauci-tweet/index.html

Egan, L. (2020, February 29). Trump Calls Coronavirus Democrats’ ‘New Hoax.’ NBC News Available at: https://www.nbcnews.com/politics/donald-trump/trump-calls-coronavirus-democrats-new-hoax-n1145721

Fintel, B., Samaras, A. T., & Carias, E. (2009, July 28). The Thalidomide Tragedy: Lessons for Drug Safety and Regulation. Helix. Available at: https://helix.northwestern.edu/article/thalidomide-tragedy-lessons-drug-safety-and-regulation

Henderson, C. (2020, April 29). Holly Marie Combs Blames Trump for Grandfather’s COVID-19 Death: ‘He Believed Every Lie.’ USA Today. Available at: https://www.usatoday.com/story/entertainment/celebrities/2020/04/28/holly-marie-combs-blames-trump-grandfathers-covid-19-death/3045687001/

Johnson, A. F., Pollock, W., & Rauhaus, B. (2020). Mass Casualty Event Scenarios and Political Shifts: 2020 Election Outcomes and the U.S. COVID-19 Pandemic. Administrative Theory & Praxis, 42(2), 249–264.

LeBlanc, P. (2020, May 5). Fauci Says Calls for His Dismissal are ‘Part of the Game.’ CNN News. Available at: https://www.cnn.com/2020/05/04/politics/fauci-coronavirus-cnntv/index.html

Liptak, K., & Acosta, J. (2020, May 13). Trump Privately Questions Whether Coronavirus Deaths are Being Overcounted as Fauci Projects the Opposite. CNN News. Available at: https://www.cnn.com/2020/05/13/politics/trump-fauci-coronavirus-deaths/index.html

Milman, O. (2020, March 31). Seven of Donald Trump’s Most Misleading Coronavirus Claims. The Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2020/mar/28/trump-coronavirus-misleading-claims

Segers, G. (2020, May 14). Ousted Virus Expert Rick Bright Warns of ‘Darkest Winter in Modern History.’ CBS News. Available at: https://www.cbsnews.com/news/rick-bright-whistleblower-hhs-testimony-house-of-representatives-coronavirus-research-today-2020-05-14/

Authors:

Kat Williams & Scott R. Stroud, Ph.D.

Media Ethics Initiative

Center for Media Engagement

University of Texas at Austin

September 14, 2020

Image: Charles Deluvio / Unsplash / Modified

This case study is supported by funding from the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. It can be used in unmodified PDF form for classroom or educational settings. For use in publications such as textbooks, readers, and other works, please contact the Center for Media Engagement.

Ethics Case Study © 2020 by Center for Media Engagement is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0