SUMMARY

Finding common ground with people you disagree with isn’t easy. Americans increasingly dislike and distrust people they disagree with politically, which can be harmful in a democracy.1 In this study, the Center for Media Engagement wanted to find out what habits were more common among people that buck this trend and don’t demonize those they disagree with. We found that:

- People who want to talk about political differences – rather than avoid the topic – are less likely to have negative views or prejudiced beliefs about people from the opposite political party.

- People who frequently discuss politics with neighbors they disagree with are less likely to have negative views about people from the opposite political party – but they may view that party with more prejudice.

- People who get along with neighbors they disagree with have less negative views toward the political party they disagree with, but there was no link to feelings of prejudice.

Our findings show that, though it may be tempting to avoid talking about political differences, people who are willing to have the tough conversations tend to have less negative views of members of the opposite political party and are less prejudiced against them. Given that we also found that people who frequently discuss politics with neighbors they disagree with could be more prejudiced toward the opposite party, it may be that having discussions with people you disagree with is helpful only up to a certain point or under certain circumstances.

THE PROBLEM

Americans are growing further apart. Republicans and Democrats dislike each other more than in previous decades.2 This has democratic consequences, such as leading to gridlock in Congress.3 It even has consequences outside the political arena. For example, studies show that Americans increasingly dislike the idea of family members marrying someone from a political party they disagree with, and that partisans discriminate against each other in professional settings.4

A recent Center for Media Engagement study shows that people can have fruitful conversations with those they disagree with politically if they take actions like focusing on the people, not the politics, or looking for common ground in beliefs.5 This project tackles the idea from a different angle – by looking at the attitudes and behaviors of people who manage to find common ground with those they disagree with.

This research is part of our connective democracy initiative, funded by the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. Connective democracy seeks to find practical solutions to the problem of divisiveness.

KEY FINDINGS

- People who want to talk about political differences – rather than avoid the topic – are less likely to have negative views or prejudiced beliefs about people from the opposite political party.

- People who frequently discuss politics with neighbors they disagree with are less likely to have negative views about people from the opposite political party – but they may view that party with more prejudice.

- People who get along with neighbors they disagree with have less negative views toward the political party they disagree with, but there was no link to feelings of prejudice.

IMPLICATIONS

It may be tempting to avoid talking about political differences with people who disagree with you. Our findings, however, show that people who engage in such conversations tend to have less negative views of members of the opposite political party and are also less prejudiced against them.

Talking with people who disagree with you is important because it may bring opportunities to learn from others. But it also has the potential to backfire. Our findings show that people who talked more frequently with neighbors they disagree with were more likely to have prejudicial feelings toward the opposite political party even though they were less likely to favor their own party over the out-party. It may be that having discussions with people you disagree with is helpful only up to a certain point or only under certain circumstances. If, for example, you spend a lot of time arguing with someone you not only disagree with but also dislike, it may make things worse. If, on the other hand, you spend a lot of time talking with someone you disagree with but like and respect, it may make things better.

Another characteristic of people who have less negative views toward their out-party is that they tend to get along with their neighbors who don’t share their political views. While our study focused specifically on getting along with neighbors, having friends and acquaintances that you disagree with politically may also be helpful. These relationships could help you see that people you disagree with politically may be reasonable people, rather than the caricatures they are often cast as in the media and on social media.

FULL FINDINGS

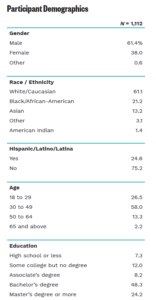

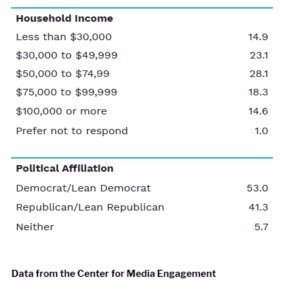

We surveyed 1,112 Americans to assess their attitudes about two types of hostility toward the “out-party,” which is the political party that people disagree with:

- Affective polarization – having negative views of the out-party while favoring members of their own party.6

- Out-party prejudice – attributing negative characteristics, such as being hateful and misinformed, to members of the other party.7

We also surveyed participants about their behaviors and attitudes regarding how frequently they discuss politics with neighbors who disagree with them politically,8 how well they get along with neighbors who disagree with them politically,9 and whether they prefer to talk about political differences or avoid such conversations.10

Then we performed statistical tests to see which attitudes and behaviors were more likely among people with less negative views and less prejudice toward the political party they disagree with.

Our results showed that the following habits were linked to people having less negative views of the opposite party:

- Frequently discussing politics with neighbors who disagree politically.

- Getting along with neighbors who disagree politically.

- Preferring to talk about political differences rather than avoiding such conversations.

When it came to prejudice toward the party people disagree with, the results were more mixed:

- Preferring to talk about political differences rather than avoiding such conversations was linked to lower levels of out-party prejudice.

- Frequently discussing politics with neighbors who disagree politically was linked to higher levels of out-party prejudice.

- Getting along with neighbors who disagree politically was not linked to out-party prejudice in either direction.

These results held up when controlling for participants’ age, gender, race, party affiliation, level of education, and strength of their partisan beliefs.11

METHODOLOGY

This project was funded by Knight Foundation as part of the connective democracy project.

We recruited 1,112 participants12 through CloudResearch, which culls participants from

Amazon Mechanical Turk. Participants had to be at least 18 years old and reside in the United States. This was not a representative nor a randomly selected sample because we specifically sought out Americans who actively follow government and public affairs13 and who live in a community that they believe has a mix of political viewpoints.14

Participants accessed the survey on their own computers or mobile devices and answered a series of questions about their political beliefs, attitudes toward people they disagree with politically, and how often they discuss politics with neighbors they disagree with.

SUGGESTED CITATION:

Overgaard, Christian Staal Bruun, and Masullo, Gina M. (August, 2020). Finding common ground: habits that may help. Center for Media Engagement. https://mediaengagement.org/research/finding-common-ground

- Hetherington, M. J., & Rudolph, T. J. (2015). Why Washington won’t work: Polarization, political trust, and the governing crisis. University of Chicago Press; Jacobson, G. C. (2016). Polarization, gridlock, and presidential campaign politics in 2016. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 667(1), 226–246; Iyengar, S., Lelkes, Y., Levendusky, M., Malhotra, N., & Westwood, S. J. (2019). The origins and consequences of affective polarization in the United States. Annual Review of Political Science, 22, 129–146. [↩]

- Iyengar, S., Sood, G., & Lelkes, Y. (2012). Affect, not ideology: A social identity perspective on polarization. Public Opinion Quarterly, 76(3), 405–431. [↩]

- Hetherington & Rudolph; Jacobson. [↩]

- Iyengar et al. [↩]

- Duchovnay, M., Moore, C., & Masullo, G. M. (2020, July). How to talk to people who disagree with you politically. Center for Media Engagement. https://mediaengagement.org/ research/divided-communities [↩]

- Affective polarization was measured using a “feeling thermometer.” Participants were given this prompt: “We’d like to get your feelings toward a number of people and groups. A rating of 0 means you feel extremely negative. A rating of 10 means you feel extremely positive. A rating of 5 means that you don’t feel particularly positive or negative.” Based on this prompt, respondents rated “Republicans” and “Democrats” on a 0-10 scale. Affective polarization was defined as the difference between feelings toward one’s in-party and feelings toward one’s out-party. [↩]

- Participants were asked: “How much do the following words describe people whose political beliefs are not the same as yours?” (1 = not at all; 7 = very much). The items were: “brainwashed,” “racist,” “hateful,” “misinformed,” and “misguided,” Mean = 4.67, Standard deviation = 1.49, Cronbach’s alpha = 0.89. [↩]

- Participants were asked, “How often do you discuss politics with neighbors who have different political views than you?” and could answer frequently, sometimes, rarely, or never. Answers were reverse-scored so that a higher number meant they more frequently discussed politics with a neighbor with different political views, M = 2.40, SD = 0.93. [↩]

- Participants rated their agreement or disagreement on a 1 (strongly agree) to 5 (strongly disagree) scale to the following: “I get along with my neighbors who don’t have the same political view as me,” M = 3.80, SD = 0.97. [↩]

- Participants were asked: “When you have different political views than people in your community, do you generally think it’s better to …” Participants could either select: “talk about these differences in order to try to find common ground” (56.5%) or “avoid talking about these differences because it usually makes things worse” (43.5%). [↩]

- These were the results of two ordinary least squares (OLS) regression analyses. When affective polarization was the dependent variable, the model was significant, R² = 0.26, Adjusted R2 = 0.26, F = 31.75, p < .001. Getting along with neighbors who disagree with you (β = -0.09, p = .001), talking with neighbors who disagree with you (β = -0.18, p < .001), and preferring to discuss differences (β = -0.15, p < .001) all showed significant relationships with affective polarization. Age (β = 0.13, p < .001), gender (β = 0.08, p = .01), race (β = 0.08, p = .01), and partisan strength (β = 0.42, p < .001) also showed significant correlations, but education and political party did not. The reference categories were female for gender and white for race. When out-party prejudice was the dependent variable, the model was also significant, R² = 0.07, Adjusted R² = 0.06, F = 6.81, p < .001. Talking with neighbors who disagree with you (β = 0.09, p = .02) and preferring to discuss differences (β = -0.09, p = .02) both showed significant relationships with out-party prejudice, but getting along with neighbors who disagree with you did not (β = -0.03, p = .38) did not. Age (β = 0.08, p = .02), being a Republican (β = -0.31, p = .001), being a Democrat (β = -0.28, p = .001) and partisan strength (β = 0.28, p < .001) also showed significant correlations, but gender, race, and education did not. In both models, partisan strength was coded as 1 = independent, 2 = lean (towards either party), 3 = weak partisan (either party), 4 = strong partisan (either party). [↩]

- The survey was conducted May 1 through June 3, 2020. A total of 1,391 people answered questions about their political views and how they discuss politics with people who disagree with them, but data from 279 were excluded from analysis because it appeared they attempted to take the survey more than once. This left 1,112 respondents. [↩]

- Participants were asked a screening question, “Would you say you follow what is going on in government and public affairs,” and were only permitted to continue with the survey if they answered “some” or “most of the time.” [↩]

- Participants were asked a screening question, “Do you feel like you live in a community where people hold different political views?” and were only permitted to continue with the survey if they answered “yes.” [↩]