SUMMARY

It can be challenging to talk to people who disagree with you politically. In this study, the Center for Media Engagement interviewed people who live in communities with a mix of political beliefs to glean their best strategies for talking to those with whom they disagree. The results offer five main approaches to talking across political differences.

- Focus on the people, not the politics

- Find common ground

- Stick to the facts and avoid confrontation

- Be an advocate, rather than an opponent

- Pick your battles

The study also revealed suggestions for putting these five strategies into action. We have outlined these approaches in the Key Findings.

THE PROBLEM

Animosity across political and social groups – where people disrespect or even hate those who believe differently than them – is one of the most pressing problems of our time.1 It leads to divisions between family members and friends, co-workers and colleagues, politicians, and the public. The acrimony between political groups makes it challenging for people and the government that serves them to solve societal problems. These divisions also cause people to become skeptical of each other, paving the way for misinformation to spread and take hold.2

In this project, the Center for Media Engagement examined best practices for talking across political differences, based on interviews with 56 Americans who live in communities with a mix of political viewpoints. This research is part of our connective democracy initiative, funded by the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. Connective democracy seeks to find practical solutions to the problem of divisiveness.

KEY FINDINGS

Our findings revealed five main strategies for talking across political differences:

- Focus on the people, not the politics

- Build a relationship before talking politics

- Don’t take comments personally

- Share your own relevant experiences

- Give a relatable hypothetical situation

- Find common ground

- Bond over less polarized issues

- Be open to listening and understanding

- Ask questions to understand a different viewpoint

- Focus on shared beliefs

- Stick to the facts and avoid confrontation

- Stick to information that can be verified

- Back up your opinions with evidence

- Limit emotion in discussion

- Avoid confrontational language

- Be an advocate rather than an opponent

- Adapt conversational style to audience

- Avoid words that might upset people

- Pick your battles

- Talk about local politics instead of national politics

- Focus on policy instead of party

- Avoid hot-button issues

We also examined if people whose own beliefs are less polarized used a different approach when talking to those they disagree with than people with more divided opinions. We found:

- Overall, both groups of people shared the same five strategies we identified

- Less polarized people reported that they frequently avoided political conversations completely or tried not to talk about politics online

- When less polarized people did talk about politics, they frequently adopted the “focus on the people, not the politics” strategy over the other approaches

SOLUTIONS

Our participants offered five main strategies for talking across political differences, as described below. All participants are identified using their chosen pseudonym.

Focus on the People, Not the Politics

This approach involves seeing the humanity in people you disagree with. “You know, maybe I didn’t know how they felt about a particular topic, but I tend not to let it change my overall view of the person,” explained Rex, 35, of Illinois. “I mean, they’re still a friend of [mine] or someone I’ve had a history with, and I try to be respectful of what they think and, so, it’s the same that I would like anybody to do for me … try to be respectful of my views.”

Focusing on the person includes building a relationship before talking about politics. Cornelius, 38, of Michigan, said he wouldn’t start talking about a political topic with someone until he knows the person. “If it’s someone new or someone who I don’t know how they’ll react. .. [I] generally won’t be the person to bring it up. … I don’t know how people will react, and I generally just try to avoid that conflict if I can,” he said.

Another aspect of this strategy, according to our interviews, is not taking comments personally and not defining people based only on their political beliefs. By separating people from their political views, our participants reported they could see past differences and focus on shared humanity.

“I’m from Brooklyn, so I grew up with, I guess, a thick skin,” explained Tim, 33, who now lives in Pennsylvania. “There’s certain things that I know that if … someone is opinionated, I know … it’s just their opinion and that’s it. … It doesn’t make any sense to take things to heart.”

Participants also sought to elicit empathy for their beliefs from those who disagreed with them by sharing stories of their own experiences. “And I said, ‘You know, I’m disabled, too. … Are you calling me a slacker?’” recalled Keith, 59, of Kentucky. “They won’t call me out because now they know a firefighter that, that’s disabled. And it doesn’t jibe with their worldview.”

Explaining a hypothetical situation can sometimes help people see a viewpoint they would not normally embrace, our participants said. Nancy, 42, of Iowa, recalled using a hypothetical situation to explain her support of government social services. “People should work. One, it gives you purpose in life. It gives you drive. It, it rewards you as a person. [It] feels valued and useful. … What if, what if this tragedy happens to you, and you mentally cannot work or physically cannot work. But you have worked. You’ve worked 20 years, and you paid your taxes. Should you not be taken care of by your community in that situation?” she asked.

Find Common Ground

Multiple people we interviewed found that it was easier to talk about divisive topics if they first bonded with people over less polarized issues.

Part of finding common ground is being open to listening to and understanding others’ viewpoints and finding parts to agree with, according to our participants. “Your whole approach, it just has to be open,” noted James, 48, of Alabama. “Like making sure you’re not using anything to, like, blatantly disagree with anybody. Just saying, ‘Yeah, but we can look at it like this’ or ‘I agree with you, but …’”

JoJo, 32, of Florida, said in her family, they try to ask questions to understand each other’s viewpoints. “Well, this is how I feel on it. … Okay, so what’s really best for everybody here?” she said. “…You know, we definitely like to discuss it and see what is actually good for the middle ground.”

Decker, 40, of Illinois, suggested focusing on shared beliefs, rather than party affiliations. “I think party politics construes and confuses the whole thing to the point where no one can know anything, and, so, they just go by the party because the party says … historically Democrats are more liberal, Republicans are more conservative,” he said.

Stick to the Facts and Avoid Confrontation

This strategy focuses on limiting emotion in discussions, sticking to information that can be verified, and avoiding confrontational language. Participants said this approach includes backing up their own opinions with evidence – such as information from news stories from reputable sources – or researching a point before engaging in a conversation.

“So, I try to do a little bit of research and find out if it’s true or fake news or whatever,” said Julie, 66, of Tennessee. “…You just got to, you just got to hope that they’re looking at more than what the talking heads on any of the networks [are saying].”

Avoiding a confrontational tone also helps head off conflict and encourages openness to differing viewpoints, participants said. “Certainly, I think they might respect me more if I’m not, you know, I don’t come off maybe as argumentative or I don’t sound like I’m attacking them,” said Kathleen, 42, of Indiana. “I think they’d be more liable to listen to me if I can, you know, back up what I’m saying and say [it] calmly.”

Sierra, 55, of Washington state, said that it’s also important to end a discussion before it gets out of hand. “Yeah, I’ll just kind of stop the conversation because it’s not getting anywhere, and I don’t want it to escalate,” she said. “… Because then people’s emotions take over when it escalates, and then they’re not … in their rational mind.”

If a discussion seems to be heating up, injecting humor into the conversation or taking a break can help. “Sometimes just to shut somebody up or to get them to go away, you know, I’ll, I’ll go, ‘You know what? I think you’ve made your point’ and … ‘I need to think about that a little bit more,’” said Matt, 46, of California. “… And walk way.”

Be an Advocate, Rather than an Opponent

This strategy involves adopting a conversational style that is more palatable to those you disagree with. Janie, 38, of Ohio, said she changes her speech style for both Democrats and Republicans to mimic what she thinks they prefer. “When I’m speaking with liberals … I talk a lot more slower. I put in a lot of, ‘um’s’ and ‘yeah, I feel ya.’ With conservatives I, I speak very clearly. I’m very conscious not to break or pause.”

Similarly, Sophia, 22, of Pennsylvania, avoids words that might upset someone. “So, like if I’m talking, my father does not believe in white privilege,” she said. “If I sit down and I try to have a conversation with him about anything regarding race and I use the word ‘white privilege,’ that’s it, the conversation’s basically done.”

Pick Your Battles

Advocates of this approach suggest talking about local politics, which might be less divisive than national politics, and avoiding hot-button issues. Joe, 49, of North Carolina, said he tries this approach on NextDoor, a neighborhood app, and on Facebook by avoiding topics that “might possibly rub people the wrong way.” Carla, 56, of Oregon, takes a similar tack. “We can talk about events like that new road going in or should we, you know, should we pass the bond for the new park measure or, you know, the local community college bond,” she explained. “We can talk about things like that. … Definitely easier to talk about local issues and even state issues.”

Other tactics people mentioned included focusing on discussions about policy – rather than focusing on particular parties, not tying particular policies to a party, and not assuming that because someone belongs to a specific party that they agree with all of that party’s beliefs. “I try to be tolerant because … there’s just so much political divide that I really just try to stick to the issues and not just try to make a generalization about a person overall,” explained Robert, 37, of Florida. “Or, for instance, if they vote a particular way, I don’t want to automatically assume … that they voted for or … have certain views that I just find very offensive.”

Some topics, however, are so intense, people said they just avoid them. “I honestly wouldn’t talk about [President Donald] Trump too much. I have opinions. I have information. I have, you know, things that I wouldn’t even bring up. I think that person would probably just leave the room. It would become very personal,” noted Kate, 46, of South Carolina.

DIFFERENCES BASED ON POLARIZATION

We were interested in seeing if people whose own beliefs are less polarized used a different approach when talking to those they disagree with than people with more divided opinions. Overall, both belief sets embraced all five strategies. We found two notable differences in how people who are less polarized approached these conversations:

- Less polarized people frequently avoided political conversations completely or tried not to talk about politics online

- When less polarized people did talk about politics, they frequently adopted the “focus on the people, not the politics” strategy over the other approaches

People with less polarized viewpoints seemed more likely to avoid political discussions than those with more entrenched opinions. But many participants mentioned avoidance as a strategy for dealing with political disagreement. People particularly avoided discussing politics if they worried a conversation was in danger of getting too heated or would impact how others viewed them. This was especially true if people lived in a community where they felt their political views were in the minority.

Some people tried to talk about politics only in person because they felt they could better convey their feelings face to face than online. Others would silence themselves or pretend to agree rather than face a conflict. “Like I’m just afraid of being berated, you know. And I don’t want to be berated,” explained Max, 36, of North Carolina. “And I don’t want to dislike you.”

Others, like, Lou, 64, of Florida, reined themselves in when they were offline but felt freer online. “I don’t do conflicts, and I don’t do drama. But when I have the urge to, I’ll go on

Facebook … and get on like a CNN post and, you know, post snarky comments to people that I think are, you know, talking crazy. I don’t do that with people that I actually know.”

Some people steered clear of political talk altogether. This was most pronounced among those who had less polarized views or those who felt their beliefs did not jibe with most people they know.

“I kind of shut down,” noted Julie, of Tennessee. “You know, I, I take the, the attitude of: Okay, this is getting us nowhere.”

But when people who were not very polarized did discuss politics, they often tried to focus on the person and not their political beliefs that they might disagree with.

“A lot of my friends are from very rural areas, and they have very different opinions than I do because I’m kind of from the city,” said 22-year-old Claire, of North Carolina. “…We’ll drink together, and we’ll talk about politics. We’ll eat dinner together, and politics will come up, and we’ll have different opinions, but it’s never a fight. It’s never like, Oh, I don’t like this person because of what they believe. I think that it helps me kind of see things clear and see kind of why people feel that way.”

METHODOLOGY

This project was funded by Knight Foundation as part of the connective democracy project. Interviews were conducted via Zoom from May 8 to June 29, 2020. Interviews ranged from 26 to 86 minutes and were recorded and transcribed.

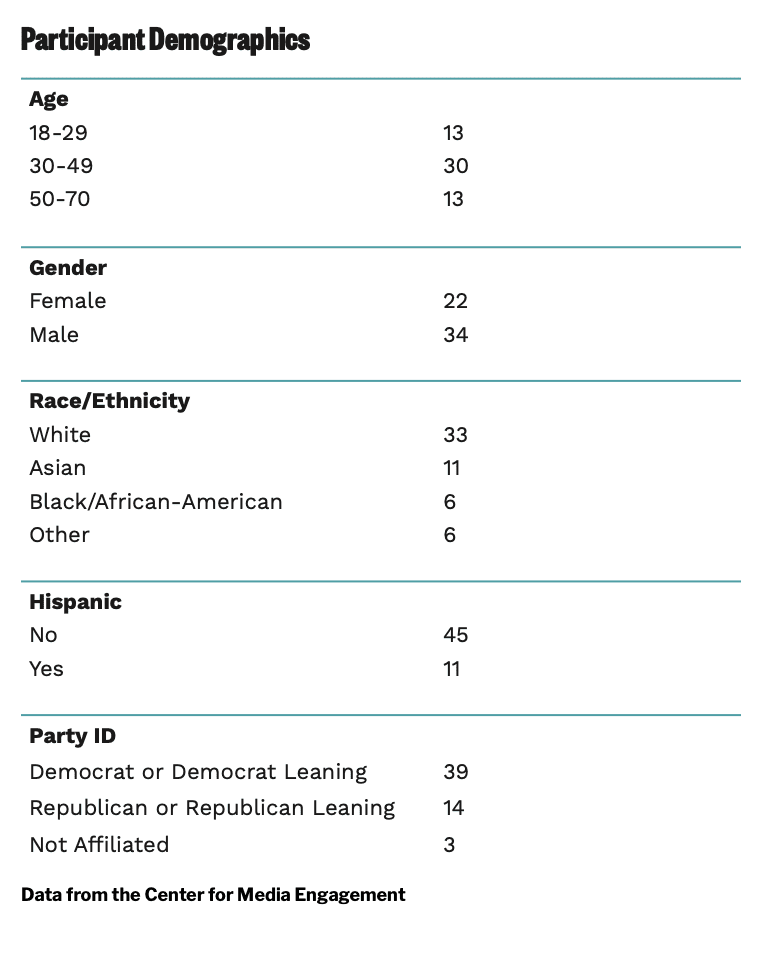

Participants had to be at least 18 years old and come from a community that had a mix of political viewpoints.3 We sought participants who were diverse in terms of age, gender, political beliefs, feelings of polarization, state of residence, and race/ethnicity. Participants were recruited through CloudResearch, an online platform that culls research subjects from Amazon Mechanical Turk.

Our sample of 56 people comprised 22 women and 34 men. They ranged in age from 20 to 70 years and included 39 people with Democrat views, 14 with Republican beliefs, and three who considered themselves not aligned with either party.4 Forty-two interview participants reported more divided viewpoints about the party they do not affiliate with, and 14 had less polarized beliefs.5 Participants hailed from 26 states.6

During interviews, participants were asked a series of questions about their communities, their political beliefs, and how they navigate talking to people who disagree with them politically. We reviewed the transcripts of the interviews to find commonalities in what people were saying and developed the categories explained above.

SUGGESTED CITATION:

Duchovnay, Marley, Moore, Casey, and Masullo, Gina M. (2020, July). How to Talk to People Who Disagree with You Politically. Center for Media Engagement. https://mediaengagement.org/ research/divided-communities

- Levendusky, M.S. (2018). Americans, not partisans: Can priming American national identity reduce affective polarization? The Journal of Politics, 80(1), 59–70; Iyengar, S., Lelkes, Y., Levendusky, M., Malhotra, N., & Westwood, S.J. (2019). The origins and consequences of affective polarization in the United States, Annual Review of Political Science, 22(1), 129–46. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-051117-073034. [↩]

- Jamieson, K.H. (2018). Cyberwar: How Russian hackers and trolls helped elect a president what we don’t, can’t, and do know. Oxford University Press. [↩]

- Participants were recruited through four surveys, conducted on May 1, May 19, June 3, and June 16. Four surveys were conducted in order to get enough participants willing to be interviewed and to ensure adequate diversity in terms of gender and race/ethnicity. Across the four surveys, a total of 1,391 people answered questions about their political views and how they discuss politics with people who disagree with them, but data from 279 were excluded from analysis because it appeared they attempted to take the survey more than once. This left 1,112 respondents. All participants were invited to be interviewed more in-depth about these topics, but they had to meet two inclusion criteria to be considered for interviews. First, they had to live in what we considered a “divided community,” defined as a community where there was a gap of 60 or fewer percentage points between the percentage of people in that ZIP code who voted for Donald J. Trump compared to the percentage who voted for Hillary Clinton in the 2016 presidential election. Voter percentages were based on an interactive graphic published by The New York Times: https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2018/upshot/ election-2016-voting-precinct-maps.html#10.95/30.465/-97.613. Additionally, participants only qualified to be interviewed if they expressed either feelings of being highly polarized or not very polarized, leaving out those who were in the middle. Polarization was measured by asking participants to rate how they felt about Republicans and Democrats on two separate 1 (extremely negative) to 10 (extremely positive) scales. We then calculated the absolute value of these scores and divided the scores into tertiles. Those in the top tertile were considered “high polarization,” those in the bottom tertile were defined as “low polarization,” and those in the middle tertile were not eligible to be interviewed. Overall, a total of 565 people met these criteria and 56 people were interviewed. Interview participants were paid $25 each for completing an interview. [↩]

- Participants were asked “generally speaking, do you think of yourself as a …,” and could select “Democrat,” “Republican,” “Independent,” or “other.” Those who responded “Independent” or “other” were then asked: “Do you consider yourself closer to the …,” and could select “Democratic Party,” “Republican Party,” or “neither.” Of the total interview participants, 36 indicated they were Democrats, 11 reported being Republicans, and the remaining nine selected Independent. Of those who selected Independent, three said their beliefs were closer to the Democratic Party, three to the Republican Party, and three said neither. [↩]

- The definition of high and low polarization scores is described in endnote 3. [↩]

- The number of interview participants from each of the 26 states is: Alabama (1), Arizona (1), California (5), Florida (6), Georgia (1), Hawaii (1), Iowa (1), Idaho (1), Illinois (3), Indiana (2), Kentucky (1), Michigan (2), Montana (1), North Carolina (8), Nebraska (1), Nevada (1), New York (3), Ohio (3), Oregon (3), Pennsylvania (3), South Carolina (1), Tennessee (2), Texas (2), Virginia (1), Washington state (1), and Wisconsin (1). [↩]