SUMMARY

The Center for Media Engagement analyzed how different buttons, such as the “Like” button, affect peoples’ responses to comments in an online comment section. We wanted to know whether buttons – and the concepts they convey – affect commenters’ behavior. In particular, we analyzed when people pressed a button corresponding with a counter-attitudinal post, or a post that conveyed a point of view that was the opposite of one’s own view. We tested whether people responded differently to counter-attitudinal comments depending on whether they saw “Like,” “Recommend,” or “Respect” buttons.

The results show that button word choices are consequential. In several instances, the “Respect” button yielded more clicks on counter-attitudinal comments than the “Recommend” or “Like” buttons. In another instance, the “Respect” button garnered more clicks overall than the other buttons.

PROBLEM

People use social media buttons, such as “Like” or “Share,” on news sites to share information with others, to indicate high-quality information, and to express their agreement.1 But it can be difficult to “Like” a post about a tragic event2 or a post that expresses a different political perspective.

Some news sites use different buttons, such as “Recommend,” “Share,” and “Follow,” rather than (or in addition to) “Like.” Others have introduced creative button labels. The Huffington Post included buttons, such as “Amazing” and “Inspiring,” that allowed readers to react to a story. Several Nexstar local television news websites had a feature that allowed readers to express whether they felt “Bored,” “Furious,” or “Happy” about a news story. The Tampa Bay Times allowed readers to click “Important,” “Inspiring,” and “Sad” in response to articles. As these examples show, several newsrooms have innovated in labeling buttons.

The words we choose can — and do — change individuals’ attitudes and decisions. It’s possible that the “Like” button encourages people to think about political issues in terms of agreement or disagreement, rather than quality, for example. In this study, the Center for Media Engagement examined a new button — “Respect” — and tested how the buttons “Like,” “Recommend,” and “Respect” affect how people engage with the news.

KEY FINDINGS

- In several, although not all, instances, the “Respect” button yielded less polarized comment section behavior than the “Like” button.

- People were more likely to click on comments that expressed their political viewpoint. In one instance, people were more likely to use the “Respect” button than other buttons.

IMPLICATIONS FOR NEWSROOMS

The results of the study suggest that button word choices are consequential. People respond differently when they can “Respect” a comment, rather than “Like” or “Recommend” it. Given the findings, we recommend the use of a “Respect” button.

In several instances, the “Respect” button yielded more willingness to click on comments from a differing political perspective compared to the “Recommend” or “Like” buttons. In particular, the “Respect” button resulted in less polarized clicks on right-leaning comments. In one case, people were more likely to click “Respect” on left-leaning comments than they were to use the other buttons.

FULL FINDINGS

Participants first answered questions about their attitudes toward right-to-work laws and gay rights, the article topics used for this study.3 They were then randomly assigned to read either a news story based on an article from The Washington Post that focused on a right-to-work law passed in Michigan or a news story based on an article from The New York Times that discussed the perspective of a Republican lesbian. We used two different articles in order to evaluate whether our findings applied beyond one topic.

After reading one of the two news stories, participants had the opportunity to engage with a comment section. Eight comments related to the article were already posted – four that expressed left-leaning political views and four that expressed right-leaning political views. Some of the comments were from the actual site commentary on the articles selected. Other comments were created and added to showcase different views and tones.

Although the comment sections were identical, we varied the available buttons. One-third of the participants saw “Like” buttons next to each comment, one-third saw “Recommend” buttons, and the final third saw “Respect” buttons.

Beside each button, a number indicated how many people had “Liked,” “Recommended,” or “Respected” the comment. The number associated with each comment was the same for all participants. When a participant clicked the button, the number increased by one. We unobtrusively tracked whether participants clicked the buttons to measure whether they interacted with the comments differently depending on the button they saw.

This design allowed us to examine three things. First, we could determine whether button- clicking behaviors differed depending on which button was present. Second, we could investigate whether people reacted differently to opposing views based on the button they saw. And third, we could analyze whether the patterns held across two news issues.

We found that the buttons did influence how people interacted with the comment section. Overall, the results support use of the “Respect” button.

Clicks in the Right-To-Work Comment Section

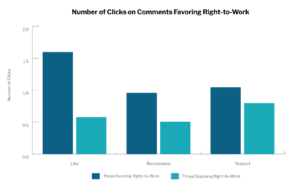

We looked at the number of times participants clicked a reaction button on comments about right-to-work laws. As expected, people were more likely to click on comments expressing a view that they shared.

For comments opposed to the right-to-work, respondents’ clicking behavior did not change depending on the text of the button.

For comments favoring right-to-work laws, the button text mattered. The “Like” button led people who favored the right-to-work to click on comments also favoring the right-to-work at much higher rates than those who opposed the right-to-work. For both the “Respect” and “Recommend” buttons, the differences between those supporting and opposing right-to- work laws were less pronounced and the “Respect” button increased counter-attitudinal clicks.4

Clicks in the Gay Rights Comment Section

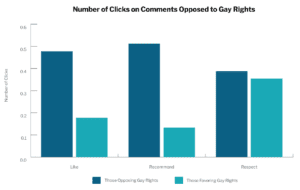

As with the right-to-work article, people were more likely to click on comments expressing a view that they shared about gay rights.

For comments favoring gay rights, the “Respect” button yielded more overall clicks than the “Like” or “Recommend” button, regardless of what the person believed. In total, people clicked an average of 1.02 times when they saw the “Like” button, 1.13 times when they saw “Recommend,” and 1.69 times when they saw “Respect.”

For comments opposing gay rights, the “Respect” button also mattered, albeit in a different way. “Like” and “Recommend” yielded similar click rates for both political views. The “Respect” button encouraged about the same number of clicks by people who opposed gay rights as the other buttons, but encouraged more clicks on right-leaning comments by people who support gay rights. In other words, people who disagreed with the comments were more likely to “Respect” them than to “Like” or “Recommend” them.6

Time with Comment Section

Participants were required to spend at least 30 seconds on the comments section before they were permitted to advance to the next survey page. After five minutes on this section, the survey automatically advanced to the next page. We evaluated whether there were any differences in the amount of time spent on the site depending on (a) which article respondents saw and (b) which buttons were on the site.

Results revealed no differences in how much time respondents spent on the site. Across all conditions, respondents spent an average of 130 seconds with the comments.

METHODOLOGY

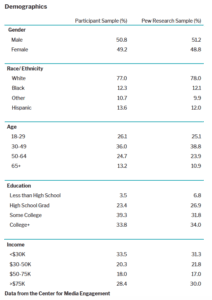

We recruited 780 people through the online survey research company Survey Sampling International (SSI). The participants, while not nationally representative, matched the demographic information of Internet users according to the Pew Research Center’s most recent findings.7 Participants had to be U.S. residents who were at least 18 years old.

SUGGESTED CITATION:

Stroud, Natalie Jomini, Muddiman, Ashley, and Scacco, Joshua. (2013, September). Engagement Buttons. Center for Media Engagement. https://mediaengagement.org/research/engagement-buttons/

- Data were gathered from a survey fielded through Amazon.com’s mTurk in August, 2012. Although the sample is similar to the United States general population in terms of gender (51% male), it is younger (M=36 years of age), more highly educated (48% with a four-year college degree or higher), and more Democratic (43% Democrat, 17% Republican) compared to the U.S. population. For this reason, the results do not represent the entire population. Although 306 respondents completed thesurvey, this portion analyzes data from the 123 respondents who said that they had hit a “like” or “recommend” button on a news article or political opinion site. Thanks to Cynthia Peacock for her assistance in developing the coding scheme and coding these articles. Reliability was assessed with two coders evaluating all of the responses to this open-ended question. Krippendorff’s alpha, a metric to measure reliability, was .88 for share information, .71 for quality article, and .74 for agreement. These reliabilities are adequate; see Krippendorff, K. (2004). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology. 2nd Ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [↩]

- Pariser, E. (2011). The filter bubble: What the Internet is hiding from you. New York, NY: The Penguin Press. [↩]

- Using questions from the Pew Research Center, respondents in the gay rights condition were asked: Do you favor or oppose allowing (1) gay and lesbian couples to enter into legal agreements with each other that would give them many of the same rights as married couples (civil unions) and (2) gays and lesbians to marry legally (1 = strongly oppose, 5 = strongly favor). We averaged the items to form one measure, with higher values indicating greater support of gay rights (M = 3.52, SD = 1.32; r = .74, p < .01). Respondents in the right-to-work laws condition were asked whether they favored or opposed laws stating that employees can hold a job regardless of whether they pay union dues (1 = strongly oppose, 5 = strongly favor) and their attitude toward unions (1 = very favorable, 5 = very unfavorable). The two items were averaged, with higher values indicating more support for right-to-work laws and unfavorable attitudes toward unions (M = 3.40, SD = 0.87; r = .32, p < .01). [↩]

- The interaction between the button displayed and right-to-work beliefs, with “like” as the reference category, for clicking on right-leaning comments was: right-to-work attitude (B=0.69,SE=0.15, p<.01), respect button (B= -0.15, SE=0.17, n.s.), recommend button (B= -0.37, SE=0.17, p<.05), right-to-work attitude x respect button (B= -0.47, SE=0.20, p<.05), right-to-work attitude x recommend button (B= -0.33, SE=0.20, p < .10). [↩]

- We controlled for education, age, gender, race/ethnicity, partisanship, ideology, and income. [↩]

- The interaction between the button displayed and gay rights beliefs, with “like” as the reference category, for clicking on right-leaning comments was: gay rights attitudes (B=- 0.11, SE=0.04, p < .01), recommend button (B=0.0005, SE=0.07, n.s.), respect button (B= 0.05, SE=0.07, n.s.), gay rights attitudes x respect button (B=0.10, SE=0.05, p<.10), gay rights attitudes x recommend button (B= -0.04, SE=0.06, n.s.). With “recommend” as the reference category, the gay rights attitudes x respect button coefficient is significant (p<.05). [↩]

- Demographics obtained from the Pew Research Center’s Internet & American Life Project August 2012 tracking survey. The Pew Research data asked a combined race/ethnicity question where we asked two separate questions. We recalculated the racial composition of the Pew data for non-Hispanic identifiers to compare with our data. [↩]