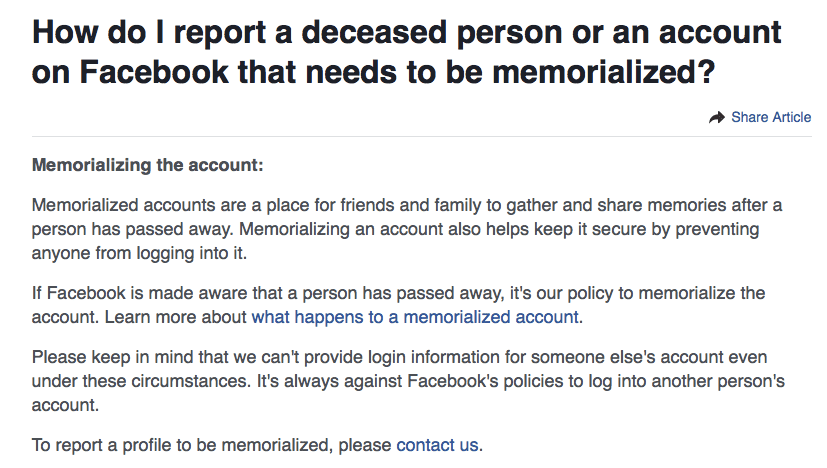

Social media has become a feature of the daily lives of many people. How will it feature in the time after their daily lives end? Most people don’t stop think about what happens to their online selves after they pass away. Who has the rights to the digital image or record of a person after they are dead? Social media platforms have been adapting to a growing presence of the online dead. When Facebook is alerted of a user death, they can freeze or “memorialize” the account. This serves two functions: first, it prevents anyone from hacking the account or gaining access to it. Second, it turns the profile into a memorial space which allows friends and family to publicly post their memories about the deceased individual.

Such memorialization prevents embarrassing “normal” online interactions with the account of the deceased such as the sending of friend requests or invitations to shared events. But are these online memorials without controversy? David Myles and Florence Millerand point out that norms have yet to be established when it comes to online mourning, which leads to controversy “regarding what constitute acceptable ways of using SNS [social network sites] when performing mourning activities online.” For example, many people may view the act of posting on a deceased person’s Facebook page as immoral or as disrespectful for close family and friends trying to privately grieve. At the same time, this digital realm of mourning could provide closure for a geographically-dispersed group of acquaintances and allow people to continue talking to their loved ones by honoring their legacy. As the Huffington Post notes, death surrounds us online, as “increasingly the announcements and subsequent mourning occur on social media.”

Such memorialization prevents embarrassing “normal” online interactions with the account of the deceased such as the sending of friend requests or invitations to shared events. But are these online memorials without controversy? David Myles and Florence Millerand point out that norms have yet to be established when it comes to online mourning, which leads to controversy “regarding what constitute acceptable ways of using SNS [social network sites] when performing mourning activities online.” For example, many people may view the act of posting on a deceased person’s Facebook page as immoral or as disrespectful for close family and friends trying to privately grieve. At the same time, this digital realm of mourning could provide closure for a geographically-dispersed group of acquaintances and allow people to continue talking to their loved ones by honoring their legacy. As the Huffington Post notes, death surrounds us online, as “increasingly the announcements and subsequent mourning occur on social media.”

Facebook’s memorialization policy can be seen as a way to protect the privacy and dignity of the deceased. But the initiation of the memorialization process does not have to come from special agents such as one’s lawyers, parents, or relational partners. This feature of Facebook’s memorialization process came into focus in the aftermath of the tragic death of a 15-year-old German girl in 2015. The girl died when a train struck her at a Berlin railway station and a loyal friend quickly reported her death to Facebook, initiating the memorialization process. Only at a later point did the deceased girl’s parents wonder if her Facebook messages could answer questions about her death being a suicide spurred on by online bullying. The girl’s mother reported having her daughter’s login information, but she could not access the account because of its “memorialized” status. Facebook refused to budge from its policy governing locked memorial accounts, since the conversations people have on Facebook messenger are considered private and often involve third parties. Facebook stated that they were “making every effort to find a solution which helps the family at the same time as protecting the privacy of third parties who are also affected by this.” Revealing the daughter’s messages may prove the existence of online bullying, but it would surely reveal conversations between the girl and various parties—bullies and non-bullies—that all or some of the participants thought were private. The German court system eventually agreed that this concern for privacy was paramount, ruling that the parents “had no claim to access her details or chat history,” and that this decision was “based on weighing up inheritance laws drawn up almost 120 years ago.” The parent’s need to know (and to respond to any bullying) was judged as less important than upholding a predictable and general principle of privacy governing the exchange of messages between third parties that affected a vast majority of social media users.

Even though this tragic case is unusual, it highlights the challenges Facebook and its users are navigating as more and more Facebook users wind up dead. How do we deal with the fact that social media is, in some ways, quickly becoming a virtual graveyard? How do we deal with the digital remains of friends, loved ones, and strangers in a way that respects the living and the dead?

Discussion Questions:

- What is the best way to treat the digital remains of those who have died? How is this optimal for the deceased—and those still living on social media?

- Do you agree with Facebook’s policy on not allowing access to messages of the deceased? If you disagree, how would you protect the privacy interests of third parties who corresponded with the deceased individual?

- If the parents of the deceased girl wanted access to her emails for a less pressing matter—perhaps to gather more material to remember her by—would this alter your stance on the strong privacy stance taken by Facebook concerning memorialized accounts?

- What do you want done to your social media accounts, if any, after you die? What ethical values do your choices emphasize?

Further Information:

Kate Connolly, “Parents lose Appeal over Access to Dead Girl’s Facebook Account.” The Guardian, May 31, 2017. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2017/may/31/parents-lose-appeal-access-dead-girl-facebook-account-berlin

David Myles & Florence Millerand. “Mourning in a ‘Sociotechnically’ Acceptable Manner: A Facebook Case Study.” In: A. Hajek, C. Lohmeier, & C. Pentzold (eds) Memory in a Mediated World. 2016. Palgrave Macmillan, London. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1057/9781137470126_14

Jaweed Kaleem, “Death on Facebook Now Common As ‘Dead Profiles’ create vast Virtual Cemetery.” The Huffington Post, December 6, 2017. Available at: https://www.huffingtonpost.com/2012/12/07/death-facebook-dead-profiles_n_2245397.html

Authors:

Anna Rose Isbell & Scott R. Stroud, Ph.D.

Media Ethics Initiative

University of Texas at Austin

April 12, 2018

This case study can be used in unmodified PDF form for classroom or educational settings. For use in publications such as textbooks, readers, and other works, please contact the Center for Media Engagement.

Ethics Case Study © 2018 by Center for Media Engagement is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0