Taking creative liberty in film-making is not uncommon. In films based on historical events, facts are often morphed to create drama or align with the director’s desired message. Some facts about historical people or events aren’t known, but filmmakers may need to add such details to their works for aesthetic or dramatic purposes. But how much liberty should we allow filmmakers when someone’s reputation is at risk? Upon its December 13, 2019, theatrical release, Richard Jewell landed at the center of this debate. Directed by Clint Eastwood, the film tells the story of Richard Jewell, the security guard wrongly accused of attempting to bomb the 1996 Atlanta Olympics; in reality, he had actually helped clear the crowd from the area threatened by a reported bomb and saved hundreds of lives. Kathy Scruggs, the Atlanta Journal-Constitution journalist who reported that Jewell was being investigated, plays a major role in the film. Scruggs’ character, played by Olivia Wilde, is depicted as sleeping with the FBI agent who informed her that Jewell was a suspect.

Outside of the film’s narrative, there is no evidence that Scruggs exchanged romantic favors for information. Kent Alexander and Kevin Salwen, the authors of The Suspect: An Olympic Bombing, the FBI, the Media, and Richard Jewell, the Man Caught in the Middle, surveyed the evidence over the course of five years of research on the high-profile case, and never came across any indication that Scruggs ever used sex to get her stories (Miller, 2019). Does the insertion of this element into the dramatized film cross the line in tarnishing Scruggs’ reputation? Not necessarily, argue Hollywood studies and directors. Fabricating unknown or ambiguous parts of story lines or emphasizing some historic elements over others often improves the overall film experience, and audiences have grown to expect dramatization and some creative liberty to make a great film.

Nevertheless, the Atlanta Journal-Constitution sent a letter to Warner Bros., director Clint Eastwood, and screenwriter Billy Ray demanding that a statement be released informing the public that some events in the film were imagined for dramatic purposes, in addition to adding a disclaimer as part of the film itself. Warner Bros. responded, “It is unfortunate and the ultimate irony that the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, having been a part of the rush to judgment of Richard Jewell, is now trying to malign our filmmakers and cast” (Garvey, 2019). It turns out a disclaimer already existed at the end of Richard Jewell that explains, “Dialogue and certain events and characters contained in the film were created for the purposes of dramatization” (Jones, 2019). The company contends that this statement is sufficient in informing viewers that caution is needed in deciphering fact from fiction. Many films use similar phrasing without specifying which scenes or character qualities were manipulated.

Yet Poynter reporter Tom Jones writes, “That disclaimer hardly excuses saying an actual person did something as unethical as sleeping with a source just for the sake of ‘dramatization.’” One could also raise concerns about the vagueness of the disclaimer—it states that certain things are altered, but viewers may be hard pressed to identify which parts of this film reflect true occurrences and what parts are fictional additions. Beyond its truth or falsity, Melissa Gomez of the Los Angeles Times argues that the film’s narrative emphases perpetuate a damaging public perception of women in journalism. Gomez wrote on Twitter that “Hollywood has, for a long time, portrayed female journalists as sleeping with sources to do their job. It’s so deeply wrong, yet they continue to do it. Disappointing that they would apply this tired and sexist trope about Kathy Scruggs, a real reporter” (Miller, 2019).

Questions about this film’s treatment of women, its viewers, and the truth still linger. Are filmmakers and artists responsible for creating a vivid and moving artwork, or do they share an obligation similar to journalists to truthfully depict real life events even if it means sacrificing some of their artwork’s power and drama?

Discussion Questions:

- Did the makers of Richard Jewell do anything ethically problematic in their fictionalization of a real person? Why? What values are in conflict in this case?

- Was the studio’s response appropriate? To what extent do disclaimers provide cover for taking creative liberties while representing historical events? What problems might you anticipate if you want filmmakers to use more detailed disclaimers?

- Are there facts about this case that differentiate it from other examples of creative license? Is it possible for filmmakers to “go too far” in altering facts? If so, how would you propose defining the limit? And what is an ethical response when filmmakers exceed such a limit?

- Scruggs died in 2001 before the film was made. Does it make an ethical difference whether the person at issue is alive or dead?

Further Information:

Coleman, N. (2019, December 13). “How the Investigation Into Richard Jewell Unfolded.” The New York Times. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/12/13/movies/richard-jewell-bombing-atlanta.html

Garvey, M. (2019, December 13). “Olivia Wilde addresses controversy around her ‘Richard Jewell’ character.” CNN, Cable News Network. Available at: https://www.cnn.com/2019/12/13/entertainment/olivia-wilde-richard-jewell-kathy-scruggs/index.html

Jones, T. (2019, December 10). “Reporter Kathy Scruggs maligned in Clint Eastwood’s ‘Richard Jewell.’” Poynter. Available at https://www.poynter.org/newsletters/2019/reporter-kathy-scruggs-maligned-in-clint-eastwoods-richard-jewell-bill-hemmer-is-the-new-shepard-smith-objectified-at-work-on-air/

Lang, B. (2019, December 9). “Clint Eastwood’s ‘Richard Jewell’: Atlanta Newspaper Demands Disclaimer on Depiction of Female Reporter.” Variety. Available at: https://variety.com/2019/film/news/clint-eastwood-richard-jewell-kathy-scruggs-1203429660/

Miller, J. (2019, December 13). “The Richard Jewell Controversy—And the Complicated Truth About Kathy Scruggs.” Vanity Fair. Available at: https://www.vanityfair.com/hollywood/2019/12/richard-jewell-movie-kathy-scruggs

Authors:

Page Trotter, Justin Pehoski, & Scott R. Stroud, Ph.D.

Media Ethics Initiative

Center for Media Engagement

University of Texas at Austin

February 17, 2020

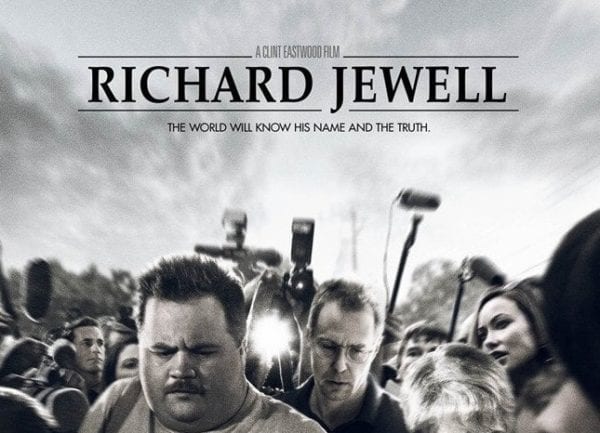

Image: Theatrical Poster / Warner Bros. / Modified

This case study can be used in unmodified PDF form for classroom or educational settings. For use in publications such as textbooks, readers, and other works, please contact the Center for Media Engagement.

Ethics Case Study © 2020 by Center for Media Engagement is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0