The Center for Media Engagement examined how clickbait content that hypes political outrage affects readers. The experiment exposed participants to articles and headlines focused on political leaders behaving in ways that include insults and name-calling, exaggeration, extreme partisanship, and obscenity.

The results showed that there is little commercial benefit and mixed democratic benefit to including outrage content in political news coverage. The effect on engagement is minimal and the reputation of the news outlet can suffer. This type of content can also add to the narrative that legitimate news is “fake news.”

The Problem

Newsrooms have employed a variety of strategies to engage audiences in today’s highly competitive digital news environment.1 In an earlier study about clickbait, we found that headlines using a question made audiences less likely to engage.

Here, we examine another type of clickbait content: outrage news. This type of news covers emotional content, such as insults and name-calling, verbal sparring, exaggeration, extreme partisanship, and obscenity.2 In this study, we look at whether news coverage that emphasizes this type of outrageous behavior by political leaders can engage or disengage news audiences.

To determine the effects of outrage coverage, we asked 1,535 study participants to read news headlines and articles about either immigration or banking regulation. The articles were attributed to a fictional news source called The News Beat. Participants viewed an outrage or non-outrage news headline and an outrage or non-outrage news article. They were then asked to answer questions about the news article and source.

Key Findings

- Outrage articles prompt perceptions of “fake news.”

- Outrage headlines decrease intended engagement.

- Readers recognize incivility in outrage news headlines and articles.

- Outrage headlines increase how much people learn from an article.

Implications for Newsrooms

This experiment looked at how people respond to news that hypes political outrage, like describing political leaders as acting in emotional and uncivil ways. Although some news outlets may believe that outrage drives engagement, our results show that newsrooms should think twice when making political news content choices. In this second CME clickbait study, we find additional evidence that clickbait-oriented content may not be so click-worthy after all, particularly when it comes to hard news and political content.

From a democratic perspective, it is concerning that people rate the news less credible when it uses outrage. Yet it is the case that individuals may learn a bit more from news articles employing such tactics.

There is little bottom-line benefit to emphasizing outrage content in political news. The reputation of a news outlet, including perceptions that it is engaged with community concerns, can suffer with little discernible effect on engagement. Although these effects are small, the experiment raises serious questions about the viability of engagement strategies that lean on outrage as an attention tool. At its worst, this type of content is adding to the narrative that legitimate news is “fake news.”

The Study

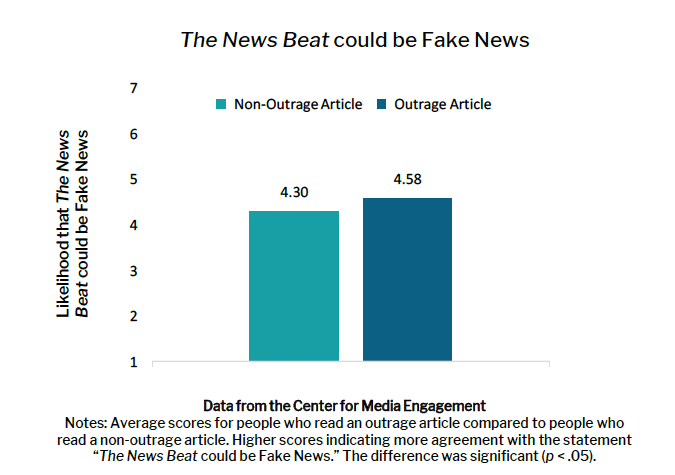

#1: Outrage Articles Prompt Perceptions of “Fake News”

Articles focused on politicians yelling at each other and refusing to make progress on issues made people more likely to agree with the statement that The News Beat could be “fake news.”3

One consequence of outrageous political behavior that others have documented is that it can decrease trust.4 In our study, we found evidence that this is also the case when newsrooms cover that outrageous behavior.

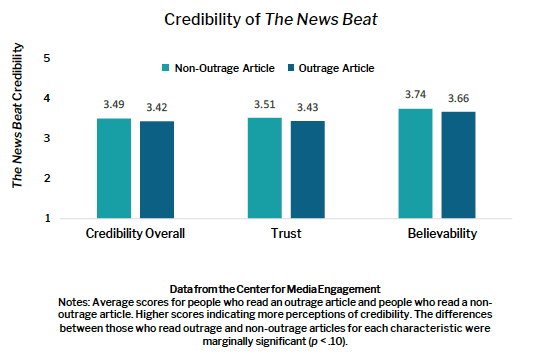

We found similar, though weaker, results when we asked participants about other types of news credibility. Participants were somewhat more likely to say that non-outrage articles were more credible, generally, and more trustworthy and believable, specifically, than outrage articles.5

We found similar, though weaker, results when we asked participants about other types of news credibility. Participants were somewhat more likely to say that non-outrage articles were more credible, generally, and more trustworthy and believable, specifically, than outrage articles.5

#2: Outrage Headlines Decreased Intended Engagement with News

#2: Outrage Headlines Decreased Intended Engagement with News

Some newsrooms lean toward outrage content due to the belief that negative news will draw audience attention.6 We find evidence that, at best, it does not increase intended engagement, and, at worst, backfires.

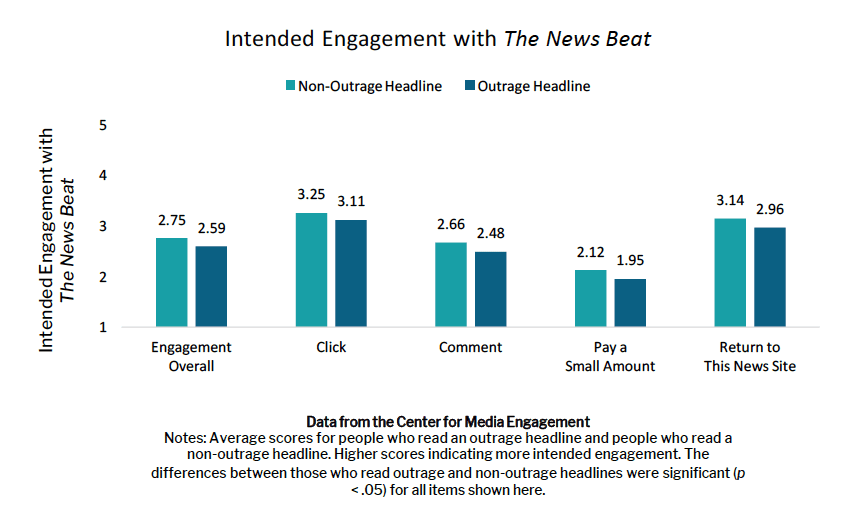

This study tracked two types of engagement. The first involved intent to engage with a news article.7 Participants who saw outrage headlines were less likely to want to engage with the article.8 When participants read an outrage headline, they were less likely to say they would click or comment on the article, pay for the article, or even return to the news site.9

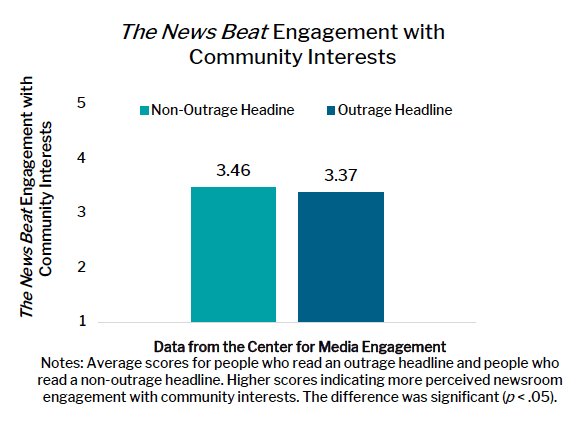

Second, we measured whether participants perceived that the news organization (i.e. The News Beat) was engaged with their community. CME has examined this perception in previous work. Participants were asked whether The News Beat: understands concerns that people like me have, is concerned with my interests, reflects my perspective in its coverage, etc. We found that perceptions of newsroom engagement were worse with outrage content. Outrage headlines prompted readers to think that the news source was less engaged with the interests of their communities.10

Second, we measured whether participants perceived that the news organization (i.e. The News Beat) was engaged with their community. CME has examined this perception in previous work. Participants were asked whether The News Beat: understands concerns that people like me have, is concerned with my interests, reflects my perspective in its coverage, etc. We found that perceptions of newsroom engagement were worse with outrage content. Outrage headlines prompted readers to think that the news source was less engaged with the interests of their communities.10

#3: News Audiences Recognize Incivility in Outrage Headlines and Articles

#3: News Audiences Recognize Incivility in Outrage Headlines and Articles

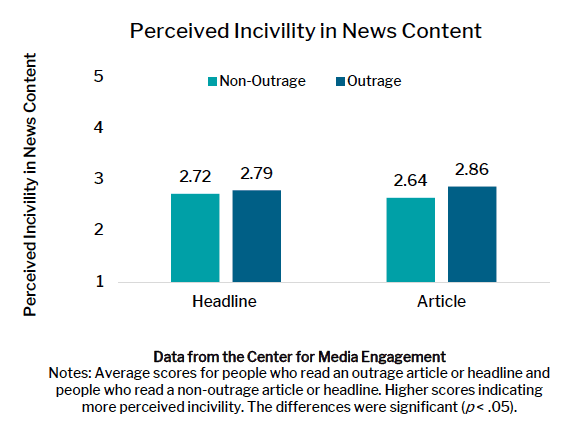

Previous research has suggested that people perceive outrage content as uncivil, and that these perceptions of incivility can decrease news engagement.11 Given this, we asked participants how uncivil—that is, how rude, uncivil, hostile, emotional, agitated, quarrelsome, uncooperative, uncompromising, and exaggerated—they perceived the news content to be. The result was that readers perceived outrage articles and headlines to be more uncivil than non-outrage articles and headlines.12

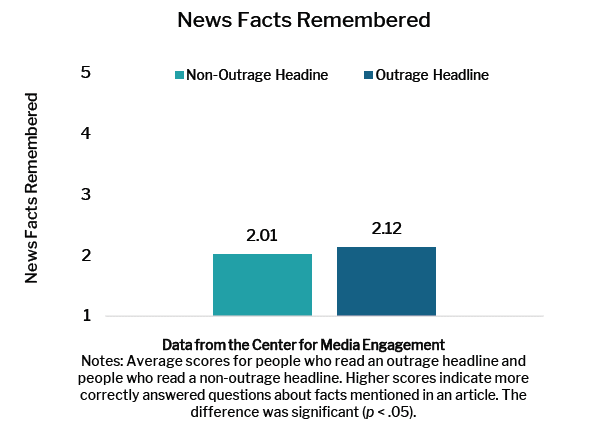

#4: Outrage Headlines Help People Remember Facts from News Articles

#4: Outrage Headlines Help People Remember Facts from News Articles

We also considered readers’ ability to remember facts from outrage and non-outrage articles. After reading the articles, participants were asked three questions about facts from the piece. When shown an outrage headline, they remembered more of the article facts than when they read a non-outrage headline.13 Even though outrage leads people to think more negatively about the news, it may simultaneously encourage them to pay more attention to the information.

Methodology

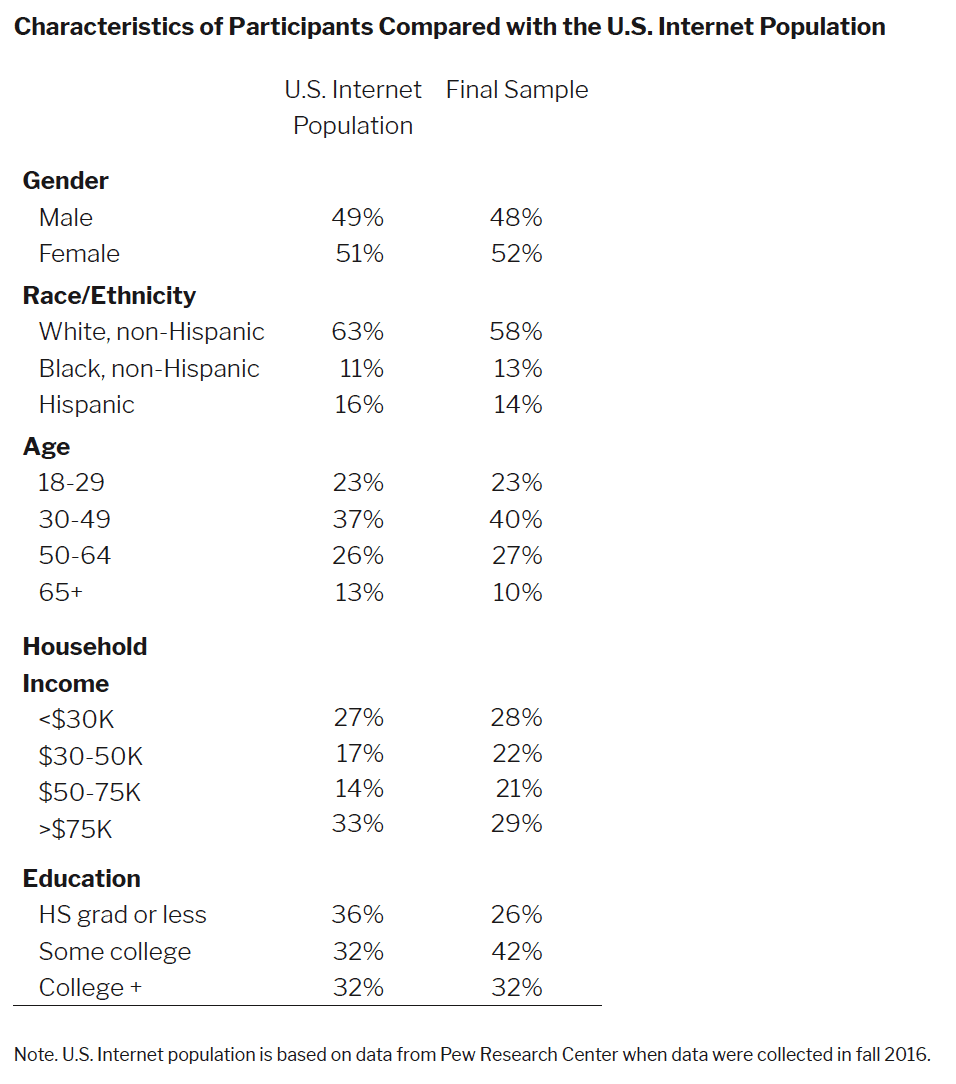

For this experiment, 1,535 participants were recruited from the United States using Research Now (formerly Survey Sampling International) in May 2018. Participant demographics were matched to the population of U.S. Internet users, according to benchmarks provided by the Pew Research Center.

Participants clicked on a link to the online study, read a consent form, and were randomly assigned to one of eight experimental conditions. The experimental conditions varied according to a 2 (outrage headline) x 2 (outrage article) x 2 (topic) experimental design.

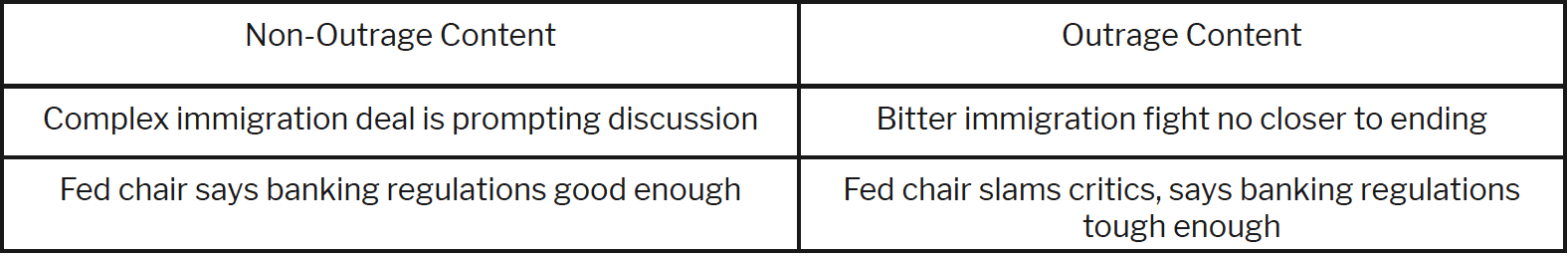

First, the groups varied by outrage headline: whether the headline emphasized heightened conflict, tense interactions among politicians, and strong emotions (“Fed chair slams critics, says banking regulations tough enough” and “Bitter immigration fight no closer to ending”) or took a less emotional approach to the same topics (“Fed chair says banking regulations good enough” and “Complex immigration deal is prompting discussion”). Content perceptions were pre-tested via Mechanical Turk.14

Second, the groups varied by outrage article: whether the article emphasized verbal fighting among political leaders, partisan gridlock, and overall disrespect or not. For instance, the outrage articles included the sentences, “Don’t spew that stuff on me – This bullcrap you guys throw out here really gets old after a while” and “Sen. Brown accused Sen. Hatch of ‘debasing the country.’” The non-outrage articles included lower levels of conflict and less emotional exchanges between political leaders. For example, the non-outrage articles included the statements, “Immigration is on the agenda. You guys know we will get to it soon” and “Sen. Brown stated Sen. Hatch was ‘losing focus.’” Content perceptions were pre-tested via Mechanical Turk.15

Finally, we also varied the issue of the article topic. We chose a more salient issue and a less salient issue for the article topics using Gallup polling data on perceptions of the “most important problem.” For a salient issue, we chose immigration. In May 2018, 10 percent of Gallup respondents reported that immigration was the most important problem facing the United States, making it the second most important problem behind general dissatisfaction with government. For a non-salient issue, we chose banking regulations. Although the economy consistently appears on the most important problems list, banking, specifically, did not appear on the list in May 2018 or in the months leading up to the experimental analysis. The results presented in this report did not significantly differ by article topic.

No matter the condition, participants were first shown a headline and lede sentence and told that they would be reading the associated news story on the next page. When they clicked to the next page, they viewed an experimental news article.16 The article was programmed to look and act like a live news article webpage and was embedded in the questionnaire to enhance the authenticity of the article. After reading the article, participants answered questions about the credibility of the news source, the likelihood that they would engage with news content, and their belief that the news source engaged with community interests. Participants also responded to questions about facts that appeared in the article. After answering these questions, participants reported their perceptions of incivility in the news content. The study ended after participants provided demographic and political background information.

SUGGESTED CITATION:

Muddiman, Ashley and Scacco, Joshua. (2019, May). Clickbait content may not be click-worthy. Center for Media Engagement. https://mediaengagement. org/research/clickbaitcontent-may-not-be-clickworthy

- See, for discussion, Kilgo, D. K., Harlow, S., García-Perdomo, V., & Salaverría, R. (2018). A new sensation? An international exploration of sensationalism and social media recommendations in online news publications. Journalism, 19, 1497–1516. http:// doi.org/10.1177/1464884916683549; Stroud, N. J. (2017). Attention as a valuable resource. Political Communication, 34(3), 479– 489. http://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2017.1330077[↩]

- Kilgo et al. (2018); Sobieraj, S., & Berry, J. M. (2011). From incivility to outrage: Political discourse in blogs, talk radio, and cable news. Political Communication, 28(1), 19–41. http://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2010.542360 [↩]

- A two-tailed t-test indicated a significant difference in agreement with the statement “The News Beat could be fake news” between participants who read a non-outrage news article and participants who read an outrage news article [t(1549) = -3.633, p < .001]. [↩]

- Work examining the effects of incivility in politics and news has, for instance, found that uncivil exchanges among political candidates can decrease political trust and that uncivil online news comments can prompt audiences to think more negatively about a news organization. See the following for more details: Mutz, D. C., & Reeves, B. (2005). The new videomalaise: Effects of televised incivility on political trust. American Political Science Review, 99(01), 1–15. http://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055405051452; Searles, K., Spencer, S., & Duru, A. (forthcoming). Don’t read the comments: the effects of abusive comments on perceptions of women authors’ credibility. Information Communication and Society. http://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2018.1534985; Tenenboim, Ori, Chen, Gina Masullo, & Lu, Shuning. (2019, January). Attacks in the comment sections: what it means for news sites. Center for Media Engagement. https://mediaengagement.org/research/attacks-in-the-comment-sections [↩]

- A series of two-tailed t-tests indicated marginally significant differences in some perceptions of news source credibility between participants who read a non-outrage news article and participants who read an outrage news article. There was a marginally significant difference in overall perceptions of credibility, a measure averaging responses to a variety of credibility items (Do you think The News Beat is: trustworthy, believable, biased, fair, objective, honest, balanced, accurate, tells the whole story, helps society, t(1528) = 1.90, p = .06). There were also marginally significant differences in two of the individual credibility items: trustworthy (t(1557) = 1.68, p = .09) and believable (t(1548.74) = 1.71, p = .09). [↩]

- Shoemaker, P. (1996). Hardwired for news: Using biological and cultural evolution to explain the surveillance function. Journal of Communication, 46(3), 32–47. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.1996.tb01487.x [↩]

- We also unobtrusively tracked actual comments, likes, and shares on the digital article. Outrage in the headline and article did not significantly increase or decrease these engagement behaviors, providing more evidence that outrage content does not necessarily prompt the desired engagement with news. [↩]

- Participants were asked to report, now that they read the news content, how unlikely or likely they would be to engage in a series of actions: click on a similar headline, like or favorite the article, share or tweet the article, leave a comment in the comment section, talk to someone about the article, pay a small fee for this article, and return to this news site. Responses to these items were averaged to create an “intended engagement” measure, with higher averages indicating more engagement. A two-tailed t-test indicated a significant difference in intended engagement between participants who read a non-outrage headline and those who read an outrage headline (t(1523) = 2.90, p < .01). [↩]

- A series of two-tailed t-tests indicated significant differences in intended engagement with some of the specific intended engagement items. For clicking on a similar headline (t(1538) = 2.15, p < .05), commenting in the comment section (t(1540) = 2.64, p < .01), paying a small feel for the article (t(1542) = 2.50, p < .05), and returning to the news site (t(1539) = 2.93, p < .01), non-outrage headlines prompted significantly more engagement than outrage headlines. The other individual measures of intended engagement (like/favorite, share, and talk) indicated only marginally significant differences at the p < .10 level. [↩]

- Participants were asked to report whether they disagreed or agreed about whether The News Beat: understands concerns that people like me have, is concerned with my interests, cares about people in my nation, is focused on helping my nation, covers what matters most, reflects my perspective in its coverage, is responsive to my nation, and cares about getting the facts right. Responses to these items were averaged to create a community engagement measure, with higher averages indicating more engagement. A two-tailed t-test indicated a significant difference in community engagement between participants who read a non-outrage headline and those who read an outrage headline (t(1523) = 2.06, p < .05). [↩]

- Muddiman, A., Pond-Cobb, J., & Matson, J. E. (forthcoming). Negativity bias or backlash: Interaction with civil and uncivil online political news content. Communication Research. http://doi.org/10.1177/0093650216685625 [↩]

- Participants were asked how rude, uncivil, hostile, emotional, agitated, quarrelsome, uncooperative, uncompromising, and exaggerated they perceived the news content they read to be. Responses to these items were averaged to create a perception of incivility measure, with higher averages indicating more perceived incivility. A two-tailed t-test indicated a significant difference in incivility perceptions between participants who read a non-outrage headline and those who read an outrage headline (t(1501) = -2.04, p < .05), as well as between participants who read a non-outrage article and those who read an outrage article (t(1501) = -6.96, p < .001). [↩]

- Participants were asked three questions about facts mentioned in the news article they read. In the articles about immigration, the questions were: (1) What government position does Chuck Schumer currently hold? (Senate Minority Leader, U.S. Senator from Utah, Director of the “Dreamer” Program, or Ambassador to Italy), (2) Democrats in Congress want protections for undocumented immigrants brought to the U.S. as children (True or False), and (3) Voters from which political party are most likely to say that immigrants strengthen the country (Republican Party voters or Democratic Party voters). In the articles about banking, the questions were: (1) What government position does Jerome “Jay” Powell currently hold? (Federal Reserve Chair, Ambassador to Italy, U.S. Senator from Utah, or Secretary of Treasury), (2) Republicans in Congress argue that regulations on Wall Street banks are not tough enough (True or False), and (3) Candidates from which political party campaigned on rolling back regulations on banks (Republican Party candidates or Democratic Party candidates). Answers were coded as correct or incorrect, then added together to create a knowledge measure than ranged from 0 correct to 3 correct. A two-tailed t-test indicated a significant difference in factual recall between participants who read a non-outrage headline and those who read an outrage headline (t(1680) = -2.12, p < .05). [↩]

- We asked participants whether the headlines were friendly/hostile, unemotional/emotional, calm/agitated, agreeable/ quarrelsome, polite/rude, uncooperative/cooperative, compromising/uncompromising, understated/exaggerated. All of the outrage headlines were, based on one-way two-tailed t-tests, perceived as significantly uncivil (Range M = 3.55, SD = 0.69 to M = 3.76, SD = 0.57) and all of the non-outrage headlines were perceived as either neutral or significantly civil (Range M = 2.74, SD = 0.66 to M = 2.87, SD = 0.82). [↩]

- All of the outrage articles were, based on one-way two-tailed t-tests, perceived as significantly uncivil (Range M = 3.35, SD = 0.76 to M = 3.65, SD = 0.72) and all of the non-outrage articles were perceived as either neutral or significantly civil (Range M = 2.89, SD = 0.69 to M = 2.90, SD = 0.61). [↩]

- For all of the stimuli, we used real news articles from local and national news agencies (e.g. The Atlantic, ABC News) as our guides. These articles are not as outrageous or sensational as those created by for-profit clickbait factories, but they reflect the boundaries of what real-life news about these issues looked like. The news articles across all of the conditions were of similar length (290 words) and reading ease (between 46.6 and 51.5). [↩]