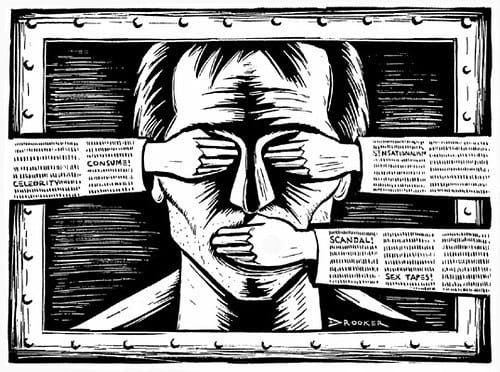

For many, there is little debate needed to reach the conclusion that Pakistan’s state sanctioned press intimidation is too harsh. One of the most pressing challenges to journalism ethics in Pakistan focuses on what the press is or is not obligated to do in response. Contemporary Pakistani laws combined with military and administrative aggression toward journalists have created a climate of self-censorship where journalists no longer act as watchdogs and informants for fear of reprisal. Self-censorship “is the worst kind of censorship, because it is done out of fear” said longtime Pakistani journalist, Ghazi Salauddin (Gannon, 2018). In response to the hostile media environment, journalists might persevere, seek greater independence, move online, or adapt to regulation, but each option is not without its own ethical considerations.

Cyril Almeida—assistant editor and columnist for Dawn—was recently named the International Press Institute’s 2019 World Press Freedom Hero for “his tenacious coverage” in reporting of the relationship between the state and militant groups and “tremendous resolve in tackling—at great risk to himself—deeply contentious issues that are nevertheless of central importance to Pakistan’s democracy” (Hashim, 2019). Almeida wrote a weekly column—discontinued in January—and interviewed an exiled former Prime Minister. As punishment for his coverage and refusal to back down from criticizing the government and military, Almeida faces treason charges, restrictions on his movement, and intimidation. Perseverance provided the citizenry with much needed information but cost Almeida much of his freedom.

On the other hand, press organizations may seek greater independence through financial divestment. Steven Butler from the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) argues Pakistan’s pressure on journalists comes in part “though the owners of media properties” (Gannon, 2018). Mohammad Ziauddin of the Pakistan Press Foundation explains that many of the business people running Pakistani media are there “not to make money, not to serve the public, but to have clout” (Gannon, 2018). In the last year, there have been layoffs and programming cuts associated with “the worst financial crisis the media industry has seen since it was liberalized,” according to Afzal Butt of the Pakistan Federal Union of Journalists (Ali, 2018). The crunch was caused by a drastic cut in government spending on media advertising because, as Saroop Ijaz of Human Rights Watch Pakistan explains, Pakistani news organizations “still rely heavily on government advertisements and subsidies” (Ali, 2018). The huge step back by the administration at once makes TV stations less beholden to government funds and thus government wishes but also makes them cash poor. As Butler asserts, “while reliance on government revenues is not a healthy model for press freedom, the sudden cutbacks have imposed extreme hardship on the media, which has had basically no time to adjust business models” (Gannon, 2018).

A third option for Pakistani journalists is to move online to less regulated and less capitally driven venues. Unfortunately, the government is cracking down on social media use by citizens but especially by journalists. They repeatedly ask companies like Twitter and Facebook to remove posts and pages and to suspend accounts. Journalist Taha Siddiqui moved to France after he was attacked but still cannot escape censorship from the Pakistani government. Reportedly, Twitter suspended his account twice in just three days because of “objectionable content that was in violation of Pakistani law” (Gannon, 2018). Several other journalists still in Pakistan, like Murtaza Solangi, have received similar notifications from Twitter that the government reported their tweets for violating the law. The problem of digital censorship is exacerbated by commonly-held impressions because, as highlighted by Asad Beyg of Media Matters for Democracy, “most accredited journalists bodies don’t recognize digital journalism as ‘real’ journalism” (Chaudry, 2018).

The CPJ advises news media owners and editors to strengthen security protocols and training, enhance self-regulation to instill confidence in accuracy and fairness, and universally condemn attacks, threats, and intimidation, potentially via professional guidelines. Almeida himself says the line of what is acceptable is drawn in terms of specificity; conflict between press and state occurs “if granular detail and specifics are reported on or commented on” (Hashim, 2019). Perhaps a solution then is to provide citizens with broad overviews of the issues and trust them to find more information for themselves, allowing journalists to serve as informants, generally, without risking censure or worse. But, if the press cannot provide details, who will? Yet, when, according to the CPJ, Pakistan’s military “restricts reporting by barring access, encouraging self-censorship through direct and indirect acts of intimidation, and even allegedly instigating violence against reporters” (Hashim, 2019), how much can we ask journalists to do?

Discussion Questions:

- Are journalists obligated to be the public watchdogs of governmental institutions even when it puts them at risk?

- Should social media companies participate in state censorship of journalism in adherence with national laws, or should they refuse such government control of information?

- What is the best way for journalists to fight state censorship of the press?

- Is there an ethical obligation for non-journalist citizens to intervene on behalf of the press? Put another way, is the reading public compelled to defend the freedoms of those institutions from which we benefit?

- What concerns might be raised by approaches that protect journalists by relying upon readers to gather more information outside of a vaguely-reported story?

Further Information:

Umer Ali, “The Pakistan government’s financial squeeze on journalism.” Columbia Journalism Review, December 20, 2018. Available at: https://www.cjr.org/analysis/journalism-pakistan.php

Suddaf Chaudry, “Pakistan: Censorship by stealth.” New Internationalist, November 15, 2018. Available at: https://newint.org/features/2018/11/15/pakistan-censorship-stealth

Kathy Gannon, “Pakistan’s journalists complain of increasing censorship.” Associated Press, December 26, 2018. Available at: https://www.apnews.com/09e9a7466e9c4c6f878e424833e5f03c

Asad Hashim, “Pakistan’s Cyril Almeida named IPI’s World Press Freedom Hero.” Al Jazeera, April 24, 2019. Available at: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2019/04/pakistan-cyril-almeida-named-ipi-world-press-freedom-hero-190424094705064.html

Authors:

Dakota Park-Ozee & Scott R. Stroud Ph.D.

Media Ethics Initiative

Center for Media Engagement

University of Texas at Austin

October 15, 2019

Image: Bill Kerr/CC BY-SA 2.0

This case was produced by the Center for Media Engagement with support from the South Asia Institute. It can be used in unmodified PDF form for classroom or educational settings. For use in publications such as textbooks, readers, and other works, please contact the Center for Media Engagement.

Ethics Case Study © 2019 by Center for Media Engagement is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0