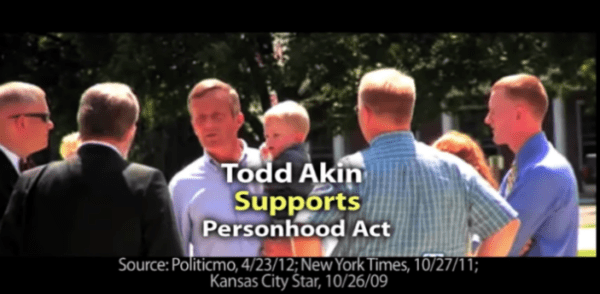

In 2012, Democratic Missouri Senator Claire McCaskill purchased $1.7 million in television advertisements focusing on one of her Republican rivals, Rep. Todd Akin. Instead of tearing him down, the ad surprisingly made claims that would endear him to Republican voters. One of McCaskill’s purchased television commercials called Akin a “crusader against bigger government” and referenced his “pro-family agenda,” finally concluding that “Akin alone says President Obama is ‘a complete menace to our civilization’” (McCaskill for Missouri 2012, 2012a).

McCaskill also ran advertisements meant to question the integrity and conservative credentials of Akin’s Republican rivals. Her advertisements attacked businessman John Brunner for an inconsistent history of voting in elections, and saying he “can’t even say where he would cut the federal budget.” Another ad called former state Treasurer Sarah Steelman “more pay-to-play,” and “just more of the same” (McCaskill for Missouri 2012, 2012b). Steelman’s campaign said the ad “further shows that Sarah Steelman is the candidate that the status quo fears the most,” while the Senate Conservatives fund (which opposed Akin but had not yet chosen one of the other candidates) said “Akin isn’t weak because he’s too conservative. He’s weak because he’s too liberal on spending and earmarks.” The Akin campaign also declined to comment on whether the ad was meant to help them: “While there is much speculation about Claire McCaskill’s strategy, what is clear is that Todd Akin has honestly and directly answered questions and unabashedly articulates a vision for the path ahead. McCaskill and other Democrats may see this as a liability; voters see this as integrity” (Catanese, 2012).

McCaskill later stated that her campaign’s goal in running these commercials for a possible opponent was to boost Akin among his Republican opponents running for the nomination: “Running for reelection to the U.S. Senate as a Democrat from Missouri, I had successfully manipulated the Republican primary so that in the general election I would face the candidate I was most likely to beat” (McCaskill, 2015). NPR matter-of-factly referred to Akin as “the Republican [McCaskill] preferred to face.” (Frank, 2012). POLITICO reported that “If there was any doubt which Republican Sen. Claire McCaskill wants to run against this fall, a trio of ads she released Thursday put it to rest.” (Catanese, 2012). There are few critiques of the strategy, and they focus on the strategy’s savviness (or lack thereof). For example, Roll Call wrote “Missouri political insiders saw the McCaskill tactic as too-cute-by-half, unless it worked, and it did.”

Debate about this strategy’s ethical dimensions was hard to come by, though the effort to aid Akin led to a campaign finance complaint: in 2015, a watchdog group filed a complaint against McCaskill for spending $40,000 polling Republican voters in Missouri and sharing findings with the Akin campaign, in excess of the $2,500 limit for an in-kind (non-monetary) campaign contribution (Scott, 2015). While the complaint was dismissed, it underscores that there were some who found McCaskill’s treatment of the Akin campaign in the Republican primary questionable (Hunter et al, 2015).

McCaskill acknowledged that this tactic of helping weaker political opponents succeed brought with it political worries: “I was fully aware of the risk and would have felt terrible if Todd Akin had become a United States senator. On the other hand, if you went down the list of issues, there was not a dime’s worth of difference among the three primary candidates on how they would have voted if they had become senators.” Yet McCaskill’s campaign team thought there was something different about Akin, something that they could exploit to win the election for the senate seat. McCaskill went on to defeat him in the general election after he made comments about “legitimate rape” rarely resulting in pregnancy, bolstering the extreme image McCaskill’s campaign had set out to create (Cohen, 2012).

Some are not convinced that this is an ethical strategy for a political candidate to utilize. Even if the ads were factually accurate, the motivations behind the ads were not as transparent as most political advertisements are (“I’m candidate X, I approve this message because I want to defeat this person I am attacking”). If democracy is concerned with placing the best leaders in positions of power through advocacy and votes, McCaskill could be indirectly helping to elect someone that might be less qualified than his rivals. Even if the gamble paid off with her victory, some would worry that the tactic involved deception about her true motives—her ads were not really meant to echo her or her campaign’s views of Akin’s liabilities (such as abortion, on which she later campaigned aggressively and effectively against Akin), but instead used appeals targeted to Republican primary voters so that they would pick a candidate against their electoral interests. By pressing the right Republican “buttons” with her praise, critics could worry that McCaskill’s ads represent the kind of manipulative communication that we want to discourage in political discourse. In the eyes of skeptics, this sort of strategic communication was an ethical risk that might reduce voter trust in any message from McCaskill’s campaign.

Beyond this particular election, McCaskill’s strategy of bolstering her most beatable opponent raises larger ethical issues in political communication. Candidates are free to produce persuasive ads, including ones that are emotionally powerful in their provocative wording, claims, and imagery. But advocating for someone one believes would be a disastrous Senator, should they win, seems deceptive. Even if the information in the advertisement was accurate, running an advertisement subtly encouraging voters to vote for Todd Akin for a purpose other than electing Todd Akin to the U.S. Senate could undermine voters’ faith in both the information they’ve been given and in the political process itself. If voters knew that the McCaskill campaign’s motivation for attacking Akin was to help Akin win a Republican primary, would they receive the message the same way, and would this tactic feed into cynicism about the political process?

Are political advertisements best thought of as a reflection of what a candidate believes, and what they want us to believe about them or their opponents? Or are they simply tools to motivate or demotivate certain behaviors by voters? With our enhanced ability to distance messages from one speaker (through real or fake organizations, super PACs, and so forth), and with our technological ability to crunch data to target specific messages to specific groups, what are the ethical limits on the creative and strategic messaging a campaign uses?

Discussion Questions:

- Should campaigns devote resources to advancing or helping prospective opponents who hold views they truly believe are dangerous or extreme?

- If you were a campaign manager, could you live with the prospect (however unexpected) of this candidate being elected?

- What is your threshold for your opponent where you could not entertain the possibility of “helping” them?

- There is always the possibility that your decision will become publicly known. In the event “your” candidate is successful and you face them in a general election, are your attacks against them less credible if it becomes known that you helped put them closer to elected office?

- If you were in a competitive primary and one of your opponents was helped by the opposing party, would you have the same reaction to the ethics of the situation?

Further Information:

Catanese, David. 2012, July 19. “McCaskill meddles in GOP primary.” POLITICO. Available at: https://www.politico.com/story/2012/07/mccaskill-meddles-in-gop-primary-078737

Cohen, David. 2012, August 19. “Earlier: Akin: ‘Legitimate rape’ rarely leads to pregnancy .” POLITICO. Available at: https://www.politico.com/story/2012/08/akin-legitimate-rape-victims-dont-get-pregnant-079864

Hunter, Caroline C., Lee E. Goodman, and Matthew S. Petersen. 2017. Statement of Reasons of Vice Chair Caroline C. Hunter and Commissioners Lee E. Goodman And Matthew S. Petersen. Washington, DC: Federal Election Commission, https://eqs.fec.gov/eqsdocsMUR/17044406199.pdf

James, Frank. 2012, August 8. “Missouri’s Claire McCaskill Gets Clarity On Her Opponent, If Not Her Future.” National Public Radio. Available at: https://www.npr.org/sections/itsallpolitics/2012/08/08/158413422/missouris-claire-mccaskill-gets-clarity-on-opponent-if-not-her-future

McCaskill, Claire. 2015, August 11. “How I Helped Todd Akin Win — So I Could Beat Him Later.” POLITICO. Available at: https://www.politico.com/magazine/story/2015/08/todd-akin-missouri-claire-mccaskill-2012-121262

McCaskill for Missouri 2012. 2012a, July 19. “Three of a kind, one and the same: Todd Akin.” YouTube. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ec4t_3vaBMc

—. 2012b, July 19. “Three of a kind, one and the same: Sarah Steelman.” YouTube. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JwPWqg_z4EQ

Miller, Jonathan. 2012, August 7. “Missouri: Todd Akin Wins GOP Nod to Face Claire McCaskill.” Roll Call. Available at: https://www.rollcall.com/2012/08/07/missouri-todd-akin-wins-gop-nod-to-face-claire-mccaskill

Murphy, Kevin. 2012, November 6. “Missouri Republican Akin loses after comments on rape.” Reuters. Available at: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-campaign-senate-missouri/missouri-republican-akin-loses-after-comments-on-rape-idUSBRE8A60HJ20121107

Scott, Eugene. 2015, August 14. “Group accuses McCaskill of violating federal campaign finance laws.” CNN. Available at: https://www.cnn.com/2015/08/13/politics/claire-mccaskill-todd-akin/index.html

Authors:

Conor Kilgore & Scott R. Stroud, Ph.D.

Project on Ethics in Political Communication / Center for Media Engagement

George Washington University / University of Texas at Austin

May 7, 2020

This case study is supported by funding from the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. It can be used in unmodified PDF form for classroom or educational settings. For use in publications such as textbooks, readers, and other works, please contact the Center for Media Engagement.

Ethics Case Study © 2020 by Center for Media Engagement is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0