EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Anonymity is essential to a free society because it provides freedom to seek information and express ideas even if they are critical or generally unpopular.1 Yet having such rights does not guarantee that people will engage in these behaviors – or that different groups of citizens will display the behaviors in similar ways.

In this report, the Center for Media Engagement provides one of the first efforts to document the frequency with which people engage in various anonymous civic participation behaviors – both as senders and receivers. Second, it examines how those anonymous behaviors might vary based on key identity-centered differences among communicators. We found that:

- The most frequent anonymous behaviors (averaging a few times each year) were anonymously searching for information online, completing anonymous surveys/polls, and reading/hearing about anonymous government leaks.

- The least frequent anonymous behaviors (averaging once or twice in a three-year period) were blowing the whistle anonymously, anonymous reports to tip lines, anonymous uploads to WikiLeaks or similar sources, receiving an anonymous complaint, and sending an anonymous letter to the media.

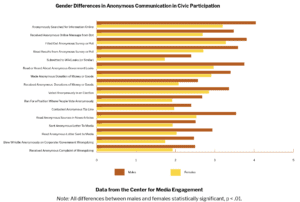

- Men engaged in every anonymous behavior assessed more frequently than did women.

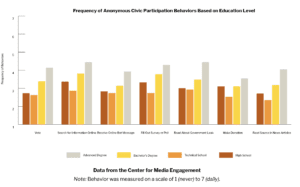

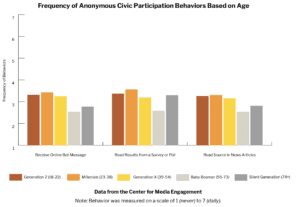

- For several different forms of civic participation, anonymous behaviors were more frequent among highly educated, younger, more liberal users who spend more time online.

BACKGROUND

The ability to communicate anonymously is regularly viewed as part of a basic right to free expression in the U.S.; furthermore, the ability to read, browse, and view information anonymously is also part of that first amendment right.2 Although online anonymity has presented some new challenges, that interpretation has been historically upheld in U.S. courts.3

People may engage in anonymous behaviors in a variety of ways – and several of these can be linked to civic participation as informed citizens. Examples might include unsigned letters sent to the media, anonymous tips or reports of wrongdoing to law enforcement or other officials, anonymous gift-giving, filling out anonymous polling or research surveys, and voting by secret ballot. Other examples might include receiving anonymous communication while searching online, reading results from anonymous polls/surveys, receiving anonymous gifts, reading news stories with anonymous sources, viewing anonymous reports of wrongdoing, and other instances of receiving such communication as a citizen in our society.

Anonymity is essential to a free society because it provides freedom to seek information and express ideas even if they are critical of the government or generally unpopular.1 Yet having such rights does not guarantee that people will engage in such behaviors. It also does not mean that different groups of citizens will display these anonymous behaviors in similar ways.

This research attempts to add to our understanding of anonymous free expression in two key ways. First, it provides one of the only efforts to document the frequency with which people in engage in various anonymous behaviors – both as senders and receivers. Second, it examines how those anonymous behaviors might vary based on key identity-centered differences among communicators. To answer these questions, the Center for Media Engagement analyzed responses gathered in late 2019 from a nationally representative sample of U.S. respondents reporting on their anonymity behaviors over the previous three years.

KEY FINDINGS

Overall, people sent and received anonymous communication with relatively low frequency over a three-year period.

- The most frequent anonymous behaviors were anonymously searching for information online, completing anonymous surveys/polls, and reading/hearing about anonymous government leaks. On average, people engaged in these behaviors a few times a year.

- Other behaviors were slightly less frequent, but still averaged just over once per year. These included voting anonymously in an election, receiving an automated message believed to be sent by a bot, reading results from an anonymous survey/poll, making anonymous donations, and reading anonymous sources in a news article.

- The least frequent anonymous behaviors were blowing the whistle anonymously, making anonymous reports to tip lines, uploading information anonymously to WikiLeaks or a similar platform, receiving an anonymous complaint from someone, and sending an anonymous letter to the media. A number of people reported never having engaged in such behaviors, though the average was once or twice in the previous three years.

- Men engaged in every anonymous behavior assessed more frequently than women.

- For several different forms of civic participation, anonymous behaviors were more frequent among highly educated, younger, and more liberal users who spent more time online.

- The most frequently used anonymous behaviors generally conveyed broader actions where individuals were not personally connected to a message source (e.g., searching for information, filling out a survey), nor were they a specific message target (e.g., reading about a government leak).

- The least frequent anonymous behaviors often indicated individuals having a sense of personal connection with a message target (e.g., blowing the whistle, contacting a tip line) or source (e.g., receiving a complaint of wrongdoing).

IMPLICATIONS

Our study revealed that people do engage in anonymous communication in relation to civic participation, even if only infrequently for most behaviors. Additionally, findings reflected associations between people’s uses of anonymous communication and their identity-based characteristics. In other words, there are systematic differences in who engaged in these anonymous civic participation behaviors. These findings and broader conclusions may be useful for political leaders and organizers, as well as citizens considering participating in anonymous ways.

- People engage in anonymous behavior primarily as a method of acquiring information, staying civically informed, and expressing views generally through voting or polls. They indicated being less likely to use established communication channels such as tip lines or WikiLeaks to anonymously speak out about issues in corporate and government contexts. Future research should seek to better understand some of the motivations behind these variations in anonymous behavior frequency, as well as how anonymous communication use may differ between more individualized (e.g., tip lines) vs. public (e.g., social media) channels.

- Men’s greater use of anonymous communication could suggest they are more comfortable with behaviors where their identity is concealed, while women value more transparent communication. This may run counter to some research suggesting women value anonymity more so than men. Our study’s focus on behaviors may be tapping into something different and indicates the need for more research considering the gendered nature of anonymous communication in civic participation. Future research might also compare gender differences among these same types of behaviors (e.g., sending letters to the media, whistle-blowing) when individuals remain anonymous vs. share their identity.

- Younger individuals and those spending more time online used more anonymous communication. Given that most behaviors examined in this study depended at least in part on mediated forms of communication, our findings could be indicative of greater exposure for these individuals, who are likely online more, to messaging and behaviors conveyed anonymously. If these and subsequent generations are more comfortable using anonymity online, we may see greater frequency of such behaviors or more use across a wider range of citizens in the future.

- The use of anonymous civic participation behaviors appears to differ based on education and political views. These differences may represent important divides in the population that manifest in the different ways citizens engage in political and other processes. If such distinctions continue to grow in a polarized society, we may see anonymous civic participation being used even more heavily by more highly educated citizens on the political left.

FULL FINDINGS

Behavior Frequency

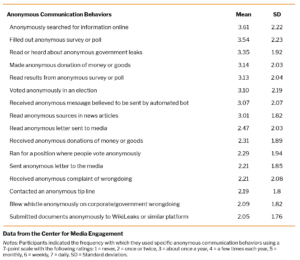

Analysis was conducted by first calculating frequency for each of the sending and receiving anonymous civic participation behaviors that participants reported using during the past three years.

The most frequent anonymous behaviors were anonymously searching for information online, completing anonymous surveys/polls, and reading/hearing about anonymous government leaks. On average, people engaged in these behaviors a few times each year. Other behaviors were slightly less frequent, but still averaged just over once per year. These included voting anonymously in an election, receiving an automated message believed to be sent by a bot, reading results from an anonymous survey/poll, making anonymous donations of money/goods, and reading anonymous sources in a news article. The least frequent anonymous behaviors were blowing the whistle anonymously, making anonymous reports to tip lines, uploading information anonymously to WikiLeaks or a similar platform, receiving an anonymous complaint from someone, and sending an anonymous letter to the media.

Identity-Based Differences

Next, to consider how people’s use of anonymous communication in civic participation varied based on identity-based differences, we tested to see if anonymous sending and receiving behaviors varied according to people’s gender, education, age, political orientation, time spent online per day, and race/ethnicity. To meet requirements for the ANOVA tests and minimize potential for bias, we did not consider significant findings that failed to demonstrate equal variance among different groups. The findings showed gender differences for every behavior examined.

There are a number of differences in anonymous civic participation behaviors based on education level. Individuals with advanced degrees were more likely to conduct anonymous searches for information online and to fill out an anonymous survey or poll compared to those who completed technical school or high school. People with advanced degrees were also more likely to make an anonymous donation compared to those who completed technical school. People with advanced degrees were also more likely to receive an anonymous online “bot” message, to vote anonymously, and to read anonymous news sources compared to individuals who completed a bachelor’s degree, technical school, or high school. Additionally, individuals with advanced degrees were more likely to read or hear about anonymous government leaks compared to people who completed a bachelor’s degree, technical school, or high school. Individuals with a bachelor’s degree were more likely to vote anonymously in any type of election compared to people with a high school diploma. Individuals with a bachelor’s degree were also more likely to read anonymous news sources and anonymously search for information online compared to people who completed technical school.

Only a handful of differences were related to age (generational cohort). Specifically, individuals identifying as Millennials or Generation X were more likely to receive anonymous messages from an automated “bot” compared to members of the Baby Boomer cohort. People identifying as Generation X were more likely to read results from an anonymous survey/poll compared to Baby Boomers. Finally, Millennials and Generation X individuals were more likely to indicate reading anonymous sources in news articles compared to members of the Baby Boomer generation.

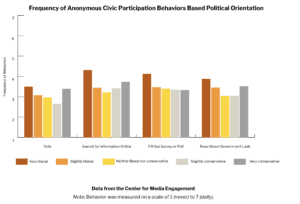

The frequency of four anonymous behaviors varied based on political orientation. People who identified as highly liberal were more likely to anonymously search for information online compared to people who had slightly liberal, moderate, or slightly conservative political views. Individuals who described themselves as highly liberal were also more likely to fill out an anonymous survey compared to those with moderate political views. Highly liberal individuals were statistically more likely than those who identify as moderate or slightly conservative to read or hear about anonymous government leaks. However, considering that highly conservative individuals’ scores were almost as strong as the highly liberal respondents, it may be that people with the most extreme political views are the most likely to encounter anonymous government leaks. Finally, people who identified as highly liberal were more likely than those who have slightly conservative political views to vote anonymously.

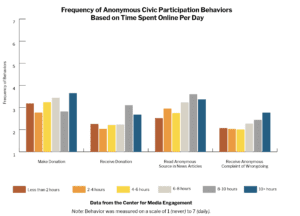

We also note four behaviors that varied based on time spent online each day. People who spent more than 10 hours online a day were also more likely to make an anonymous donation compared to people who spent between two and four hours a day online. Similarly, people who spent between eight and 10 hours per day online were more likely to have received anonymous donations compared to those who spent between two and four hours a day online. People who spent between eight and 10 hours online per day were more likely than individuals who spent less than two hours per day online to read anonymous sources in news articles. Finally, individuals who spent more than 10 hours a day online were more likely to have received an anonymous complaint of wrongdoing compared to women or those who spent between two and four hours a day online.

Overall, survey results indicated that people’s anonymous communication in relation to their civic participation varied in diverse ways based on individuals’ gender, age, education, political orientation, and time spent online. Differences in anonymous behaviors according to individuals’ race and ethnicity were also examined, although no significant differences were found.

METHODOLOGY

A representative sample — based on age, education, gender, race, income, and geographic region — of 617 respondents from the United States was recruited through Qualtrics panels to complete an online survey during the latter part of Fall 2019. To participate, respondents had to be English speakers from the U.S. and at least 18 years of age. Respondents took on average 17 minutes to complete the survey and were compensated by Qualtrics. Participation was voluntary. Survey responses where respondents skipped substantial sections of the questionnaire, provided patterned or straight-line responses, or did not meet minimal criteria for this IRB-approved study (e.g., at least 18 years old) were excluded.

Participants first responded to items assessing their identity-based demographic characteristics. In addition to the options outlined here, “prefer not to answer” was also available. For gender, respondents were asked “what gender do you identify as,” with options including female, male, and other (with an option to write in a response). Age ranges were created corresponding with generational differences: 18-22 (Gen Z), 23-38 (Millennials), 39-54 (Gen X), 55-73 (Baby Boomers), and 74+ (Silent Generation). Highest degree or level of education was collapsed into the following categories: completed some or graduated high school, bachelor’s degree, master’s/doctoral (graduate) degree, and trade/technical school. Respondents indicated their political views according to one of five options: very liberal, slightly liberal, neither liberal nor conservative (moderate), slightly conservative, and very conservative. Finally, time spent online each day was assessed according to the following categories: less than two hours, two to four hours; four to six hours; six to eight hours; eight to ten hours; more than ten hours.

After completing measures unrelated to the current study, participants responded to questions capturing the extent to which they personally used or encountered various types of anonymous communication in multiple settings. For the research reported here, we focus on 16 behaviors potentially connected to one’s civic participation in society. Table 1 lists each specific measurement item as well as their means and standard deviations. All items were assessed on the following 7-point scale that asked about behavior frequency over the past 3 years: 1 = never, 2 = once or twice, 3 = about once a year, 4 = a few times each year, 5 = monthly, 6 = weekly, 7 = daily.

SUGGESTED CITATION

Scott, C. R. & Schlag, K. (December 2022). Anonymous Civic Participation Behaviors: Gender-Based and Other Differences. Center for Media Engagement. https://mediaengagement.org/research/anonymous-civic-participation-behaviors-differences-across-gender-and-other-demographics/