As the Black Lives Matter protests erupted across the country in June 2020, Americans witnessed the power of social media as a tool for movement organization and communication. Especially in the context of the global COVID-19 pandemic, where many felt unsafe physically going outdoors to protest, showing support and solidarity online became a priority. Soon, a new method of posting infographic slideshows came to dominate Instagram; and not just for Black Lives Matter, but a wide array of injustices. From one Instagram story to the next, information about social problems was spread through minimalist slides with wide typefaces and bold colorful graphics, thereby transforming the platform from an apolitical one into one that prioritizes digital activism.

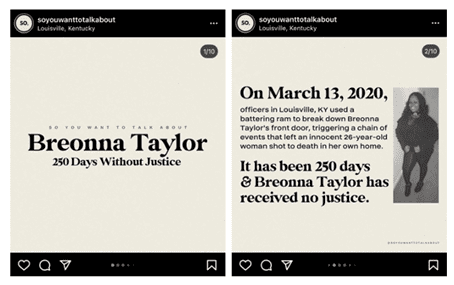

One of the most popular accounts for social justice content is @so.informed (previously known as “So You Want to Talk About”). This page regularly posts infographic slideshows about everything from updates on specific causes, like Breonna Taylor’s, to more general issues of social relevance, like “Characteristics of Fascism” or “Miscarriages.” While topics like these may seem jarring amongst the assortment of selfies and brunch photos available on Instagram, it is the page’s selection of font and colors that allow these posts to seamlessly blend into one’s timeline. In an interview with Vox, Jess (the creator of So Informed) explained:

I’m trying to appeal to the apolitical people, the ones who’d rather stay out of it and enjoy, like, mimosa pictures. I’m also trying to reach women my age, millennials who aren’t participating in the conversation because they don’t know where to start (Nguyen, 2020).

In this way, some see the infographic phenomenon as a positive addition to Instagram by bringing attention to numerous issues that might have otherwise gone unacknowledged. Because the aesthetics and incorporation of popular design elements such as floral details or line art make these heavy topics more approachable and attention-grabbing, they serve as an excellent entry point for apolitical or unaware users to become more concerned about complex social problems. Most importantly, because many infographics also include links to donation websites, templates for emailing representatives, and petitions to sign, the posts are not only educational, but provide ways for individuals to tangibly contribute to social change.

However, while some view this trend as a gateway for thoughtful activism, others are not convinced. Perhaps just as abundant as the eye-catching infographics that have flooded Instagram is the term “performative activism” – which refers to a disingenuous form of advocacy “that is done to increase one’s social capital rather than because of one’s devotion to a cause” (Ashe, 2020). One way this happens is when social media users re-post infographics (sometimes, without even reading them) to appear “woke” online when, in reality, they expend little effort to make lifestyle changes that could result in actual aid to a movement. Despite the goal to provide the digital sphere with social justice education, the popularity that these infographics have garnered is viewed by some as counterproductive.

Moreover, critics fear that reliance on social media infographics for social justice content sets a dangerous precedent. If individuals do not take the time to conduct their own research, information overload and careless consumption of media could lead to the sharing of infographics full of disinformation. One disturbing example of manipulation can already be seen as QAnon conspiracy theorists were able to blend into mainstream social media sites by camouflaging themselves with a similar Instagram aesthetic and uncontroversial hashtags like #savethechildren on their posts (Haubursin, 2020). Indeed, Vox reports that several high-profile Instagram accounts boosted inaccurate or misleading statistics stemming from QAnon conspiratorial thinking in 2020 (Haubursin, 2020). Given this evidence, the potential for others to use this format as a means for deception is not unreasonable. Hypothetically, anyone with an eye for design and a motive to mislead could create a viral infographic.

Overall, while some have applauded the Instagram infographic industrial complex for helping people become more aware of social issues and ways to help important causes, others have been skeptical whether that outweighs of all of the ways this trend has been manipulated. Because the need to amplify marginalized voices is important, and aesthetic design choices alone cannot be blamed for performative activism or the spread of misinformation, it is crucial that we consume these infographics critically. In the end, their usefulness depends completely on how users choose to interact with them.

Discussion Questions:

- What values are in conflict when deciding whether to create/re-post an infographic slideshow on Instagram?

- What is the best way for someone to engage critically with Instagram infographics? What are problematic ways of engaging or using these infographics?

- Does aestheticizing social justice to be more palatable online water down the central message of such movements? Why or why not?

- How should one manage the tension between intent and impact, or means and ends, in promoting a cause on social media?

Further Information:

Ables, Kelsey. (2020, August 15). “Selfies and Sunsets Be Gone: The Latest Instagram Trend Is PowerPoint-Style Presentations.” The Washington Post. Available at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2020/08/15/instagram-race-activism-slideshow-graphics/

Ashe, Lauren. (2020, June 23). “The Dangers of Performative Activism.” VoxATL. Available at: https://voxatl.org/the-dangers-of-performative-activism/

Berman, Hannah. (2020, July 28). “Should We Trust Instagram Infographics?” Medium. Available at: https://medium.com/age-of-awareness/should-we-trust-instagram-infographics-f80f04e1549e

Gallucci, Nicole. (2020, July 23). “Instagram is Flooded with Artsy Activism Guides. Here’s the Story Behind Them.” Mashable. Available at: https://mashable.com/article/user-made-educational-instagram-guides/

Haubursin, Christophe. (2020, October 28). “The Instagram Aesthetic that Made QAnon Mainstream.” Vox. Available at: https://www.vox.com/videos/2020/10/28/21538763/save-the-children-qanon-instagram

Hawley, Rachel. (2020, August 19). “The Lazy Liberalism of Instagram Slideshows.” The New Republic. Available at: https://newrepublic.com/article/158972/instagram-black-lives-matter-posts

Nguyen, Terry. (2020, August 12). “How Social Justice Slideshows Took Over Instagram.” Vox. Available at: https://www.vox.com/the-goods/21359098/social-justice-slideshows-instagram-activism

Authors:

Nhu Nguyen, Romi Geller, & Kat Williams

Media Ethics Initiative

Center for Media Engagement

University of Texas at Austin

January 19, 2022

Screenshot from @so.informed (previously @soyouwanttotalkabout) via Instagram

This case can be used in unmodified PDF form in classroom or educational settings. For use in publications such as textbooks, readers, and other works, please contact the Center for Media Engagement.

Ethics Case Study © 2022 by Center for Media Engagement is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0