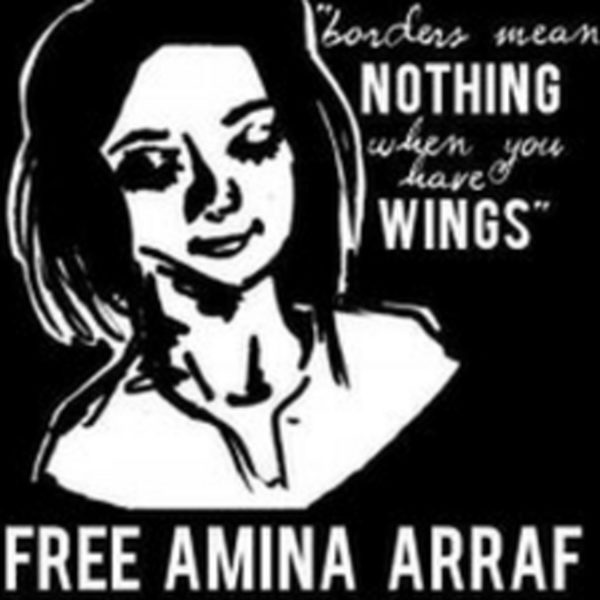

In March 2011, as the Arab Spring protests erupted across the Middle East to defy corrupt regimes throughout the region, an “unlikely hero of revolt” arose from the depths of the blogosphere to illuminate the plight of cultural and political dissidents (Marsh, 2011). Amina Arraf’s blog “A Gay Girl in Damascus” became an Internet sensation, as the bi-racial feminist wrote about her first-hand experiences with violent governmental crackdowns and secret homosexual romances in the conversative country of Syria (Marsh, 2011). The blog gained even more attention by June 2011, after her cousin reported that Arraf had been kidnapped by government agents, and supporters around the world launched various campaigns to advocate for her safe release (Addley, 2011). A week after her disappearance, Arraf was outed – Not as a lesbian, but as a hoax. In an apology letter posted to the blog, “Amina Arraf” (and the “cousin” who reported her missing) was revealed to be nothing more than a character created Tom MacMaster – a 40-year-old, heterosexual, American man attending a university in Edinburgh, Scotland (Addley, 2011).

As a Middle Eastern peace activist and co-director of the Atlanta Palestine Solidarity group, MacMaster said he was troubled by the events in Syria and wanted to “bring attention to the human rights record of a country where media restrictions make traditional reporting almost impossible” (Bell & Flock, 2011). However, his identity was viewed with suspicion, which he claimed made it difficult to effectively circulate information on his own. MacMaster told BBC News that:

In discussions on Middle East issues in the US, often when I presented real facts and opinions, the immediate reaction to someone with my name was: “Why are you anti-American? Why are you anti-Jewish?” So, I invented a name to talk under that would keep the focus on the actual issue [rather than]… the man behind the curtain. (BBC News, 2011)

MacMaster felt Arraf’s persona was necessary to “illuminate the situation [in Syria] for a Western audience” and noted that “while the narrative voice may have been fictional, the facts on [the] blog are true” (Bell & Flock, 2011 and Addley, 2011).

Despite the blogger’s seemingly good intentions, once the truth was revealed, the hoax “provoked a furious response” from blog readers and the Syrian gay community alike (Addley, 2011). Sami Hamwi, the Damascus editor for GayMiddleEast.com, argued that MacMaster “put [Syrian LGBTQ individuals and activists] in danger… and caused doubts about the authenticity [their] blogs [and] stories” (Addley, 2011). Indeed, not only could the activists have been outed and targeted themselves while trying to save a fictious figure from a fake kidnapping, but the Syrian government was also able to capitalize on the hoax and cast the Arab Spring into doubt as if the whole movement was “crafted, or instigated, by… foreigners” (Young, 2017). Ultimately, those hurt by the blog argued that MacMaster “exploited their trust and may have jeopardized their ability to use pseudonyms” (Bell & Flock, 2011).

On one hand, MacMaster successfully reported the facts of Syria’s human rights abuses and informed Western audiences about important events they otherwise would not have known about. On the other hand, he falsified his identity and potentially endangered activists on the ground to do so. Though “information from online sources has become particularly important in coverage of… countries that severely restrict foreign media” the Gay Girl in Damascus blog hoax “raises difficult questions about the reliance on blogs… and other Internet communications as they increasingly become a standard way to report on global events” (Bell & Flock, 2011).

Discussion Questions:

- What values are in conflict in the evaluation of “A Gay Girl in Damascus”?

- Do you agree with the actions MacMaster took? Why or why not?

- What could MacMaster have done differently to achieve his aims without the negative effects?

- What guidelines should blog readers adhere to when following users with unconfirmed identities?

- Under what circumstances is it in/appropriate to use pseudonyms and false personas online?

Further Information:

Addley, Esther. (2011, June 12). “Syrian Lesbian Blogger is Revealed Conclusively to be a Married Man.” The Guardian. Available at: https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-scotland-13747761

BBC News. (2011, June 13). “Gay Girl in Damascus: Tom MacMaster Defends Blog Hoax.” Available at: https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-scotland-13747761

Bell, Melissa, & Flock, Elizabeth. (2011, June 12). “‘A Gay Girl in Damascus’ Comes Clean.” The Washington Post. Available at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/lifestyle/style/a-gay-girl-in-damascus-comes-clean/2011/06/12/AGkyH0RH_story.html

Marsh, Katherine. (2011, May 6). “A Gay Girl in Damascus Becomes a Heroine of the Syrian Revolt.” The Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2011/may/06/gay-girl-damascus-syria-blog

Young, Kevin. (2017, November 9). “How to Hoax Yourself: The Case of A Gay Girl in Damascus.” The New Yorker. Available at: https://www.newyorker.com/books/page-turner/how-to-hoax-yourself-gay-girl-in-damascus

Authors:

Kat Williams & Scott R. Stroud, Ph.D.

Media Ethics Initiative

Center for Media Engagement

University of Texas at Austin

July 26, 2022

Internet Image Reproduced in The Guardian

This case was supported by funding from the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. These cases can be used in unmodified PDF form in classroom or educational settings. For use in publications such as textbooks, readers, and other works, please contact the Center for Media Engagement.

Ethics Case Study © 2022 by Center for Media Engagement is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0