SUMMARY

Protest coverage often casts protesters and their causes in a negative light, particularly when covering underrepresented groups. To help journalists frame stories in ways that do not harm these groups, the Center for Media Engagement examined two story areas of particular concern.

The results showed that stories that humanize – rather than criminalize – the person whose death sparked a protest can lead people to have more positive attitudes toward the person, the protest itself, and the protesters. Additionally, stories that legitimize protests can result in more positive attitudes toward the protest and the protesters.

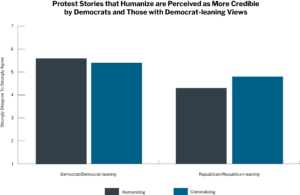

When it comes to story credibility, stories that humanize the person whose death sparked a protest can lead Democrats and those with Democrat-leaning views to perceive the news story as more credible. However, it can also lead Republicans and those with Republican-leaning views to perceive the story as less credible.

PROBLEM

Decades of research show that mainstream media tend to cover protests — particularly of underrepresented groups — in ways that cast protesters and their causes in a negative light.1

In this study, the Center for Media Engagement examined how journalists can better tell stories about protests so that they do not marginalize protesters or their causes. We focused on protests about police violence against Black people and violence against Latin American immigrants because both issues are racialized. Historically, protests challenging racism and colonialization have received the type of coverage that marginalizes or delegitimizes protesters and their causes, at least in the United States.2

This research is part of our connective democracy initiative, funded by the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. Connective democracy seeks to find practical solutions to the problem of divisiveness.

KEY FINDINGS

Participants viewed a news story about a protest that stemmed either from the death of a Black teenager shot by police or from the death of a Latin American immigrant teenager who died in a migrant detention center. We found that across both topics:

- Stories that humanized – rather than criminalized – the teenager whose death sparked the protest led people to have more positive attitudes toward the teenager, the protest itself, and the protesters.

- Stories that humanized the teenager led Democrats and those with Democrat-leaning views to perceive the news story as more credible. The opposite was found for Republicans and those with Republican-leaning views. They perceived the humanizing story as less credible.

- Stories that legitimized – rather than delegitimized – the protest resulted in more positive attitudes toward the protest and the protesters. Stories told in a legitimizing way had no effect on attitudes toward the teenager in the story or on perceptions of the story’s credibility.

IMPLICATIONS

Newsrooms should humanize – rather than criminalize – people whose deaths prompt protests, especially among underrepresented groups. Additionally, they should use language that legitimizes, rather than delegitimizes, the protests.

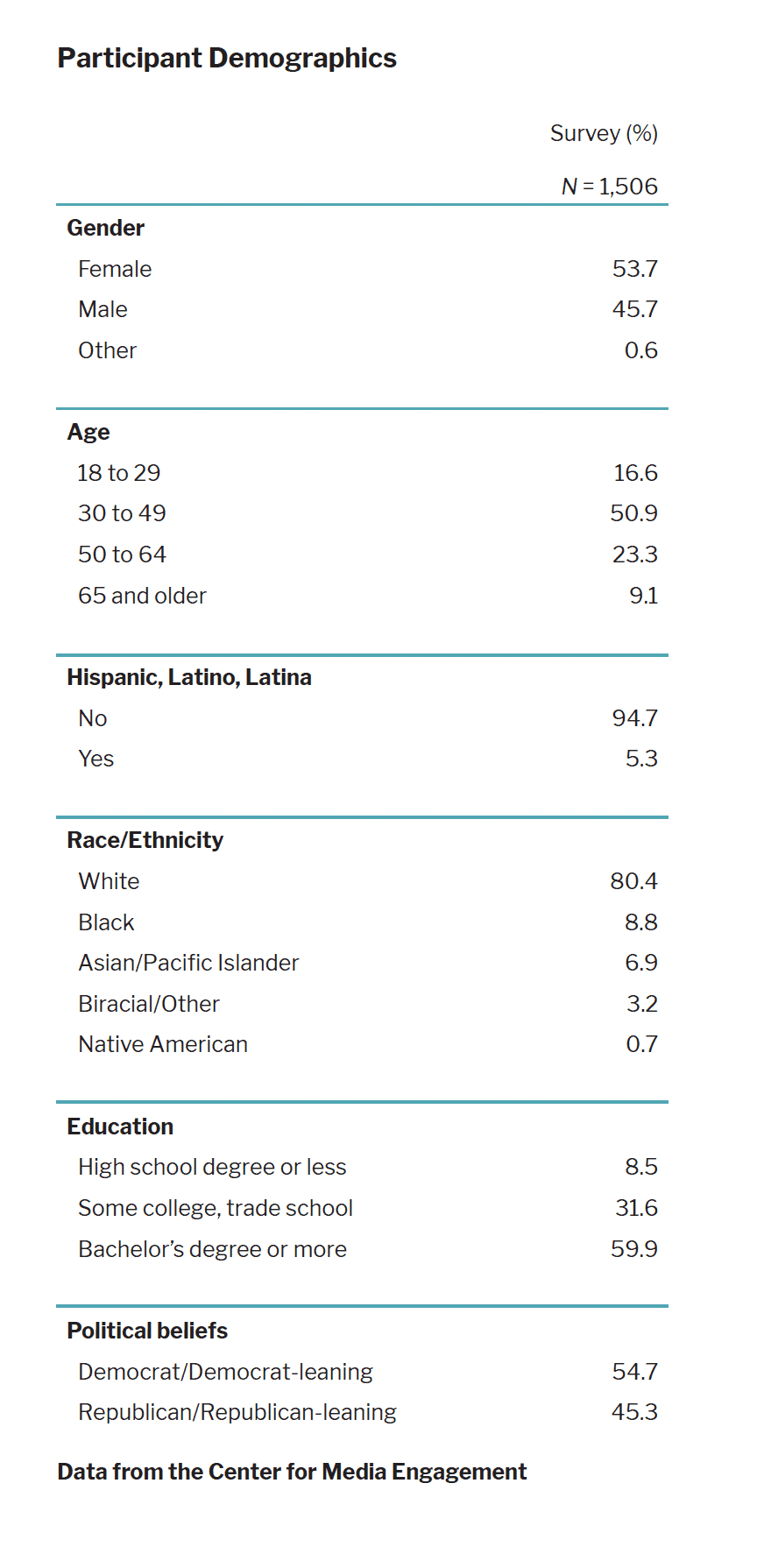

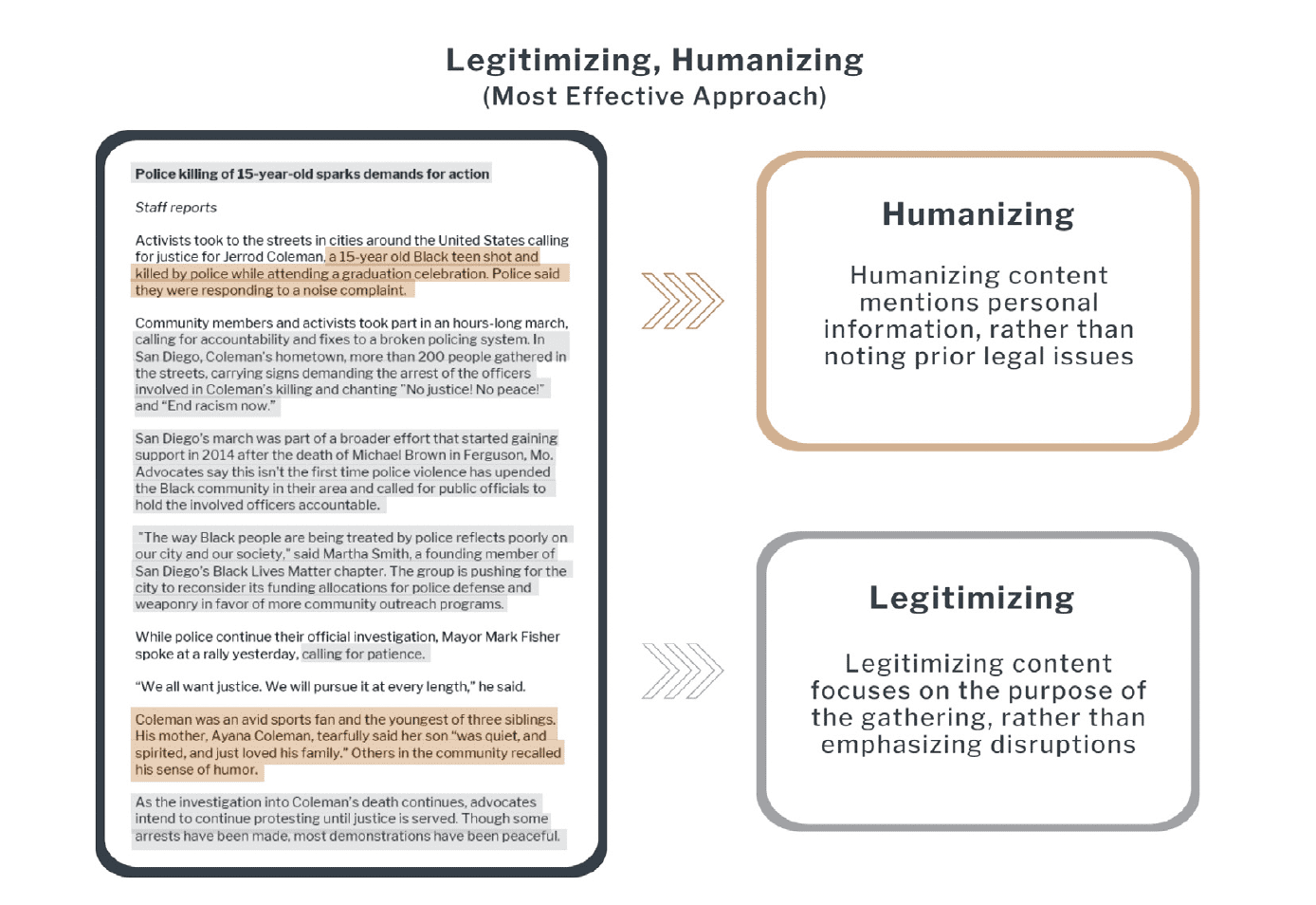

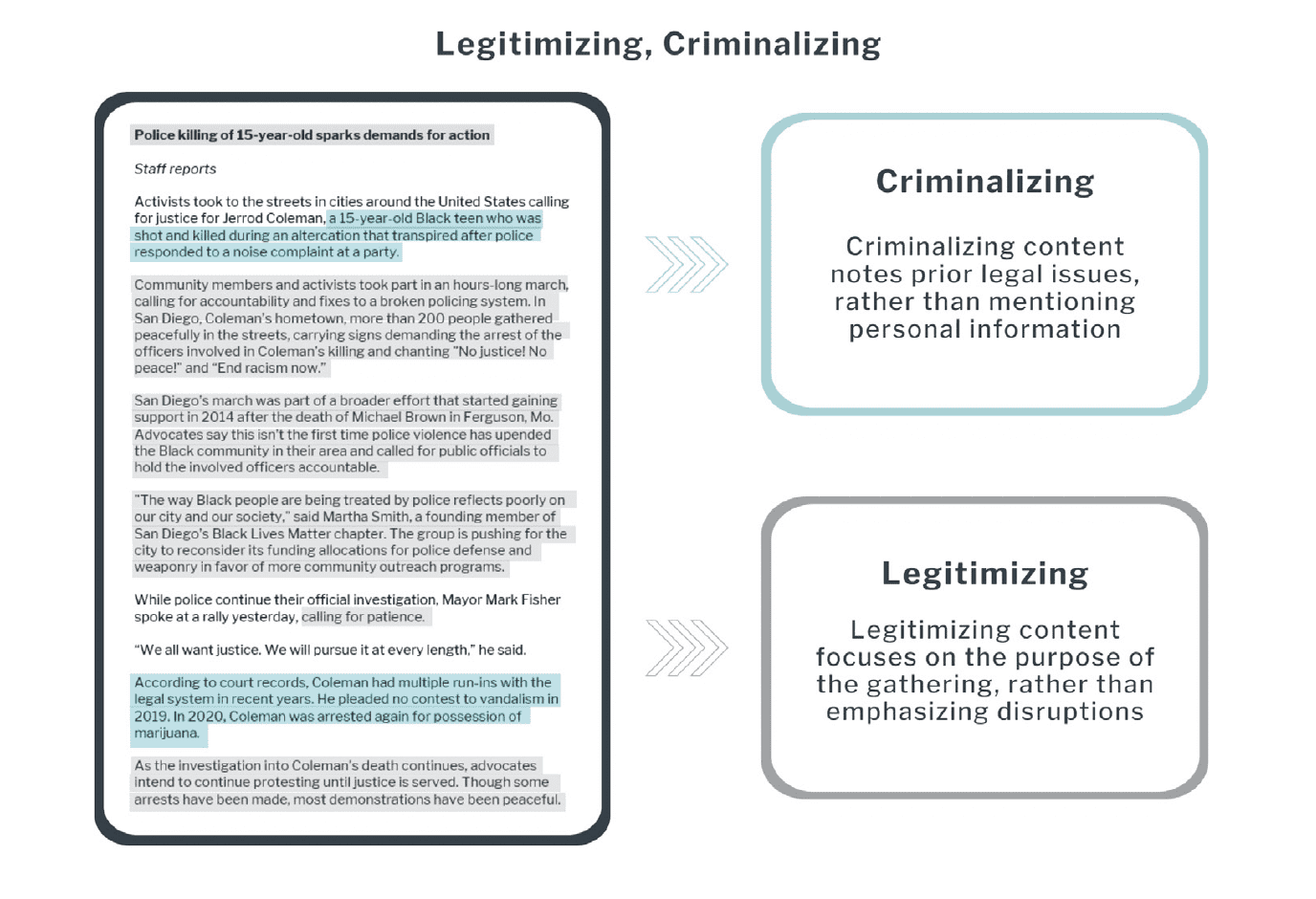

To humanize a story, reporters can mention personal information about the person who is the focus of the protest. For example, the story can touch on their personality, hobbies, family, and the circumstances that led to the protest, rather than focus on details like their criminal past or speculation about possible criminal activity.

Language that legitimizes the protest should focus on the purpose of the demonstration, rather than emphasizing disruptions. Reporters can include motivations for the protest, changes that are being called for, and background information on the broader movement and relevant past events. When stories mention protest activity and protesters’ actions, peaceful and non-radical demonstration tactics should be acknowledged, especially when isolated clashes, property damage, and violence are being discussed.

Telling stories in these ways may help people better understand the protest and the protesters, thereby running less of a risk that protesters or the protests will be delegitimized. Also, in some cases, telling stories this way may boost perceptions that the news story is credible. While this may backfire with some audiences, the benefits of telling stories in humanizing and legitimizing ways outweigh the drawbacks.

FULL FINDINGS

The Center for Media Engagement examined two story areas journalists should consider when telling stories about protests involving underrepresented groups. These were whether the person whose death spurred the protest was humanized or criminalized and whether the protest itself was legitimized or delegitimized.

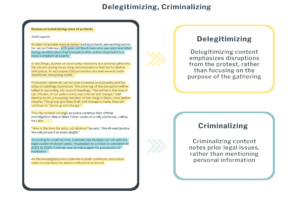

These two areas were considered because research has identified the coverage of these particular areas as problematic in protest stories.3 Humanizing stories are intended to show the person whose death spurred the protest as a human being, rather than a criminal. In our study, humanizing stories mentioned personal information about the teenager, while criminalizing stories noted prior legal issues. Stories that legitimized the protest focused on the purpose of the demonstration, while delegitimizing stories emphasized disruptions from the protest.4

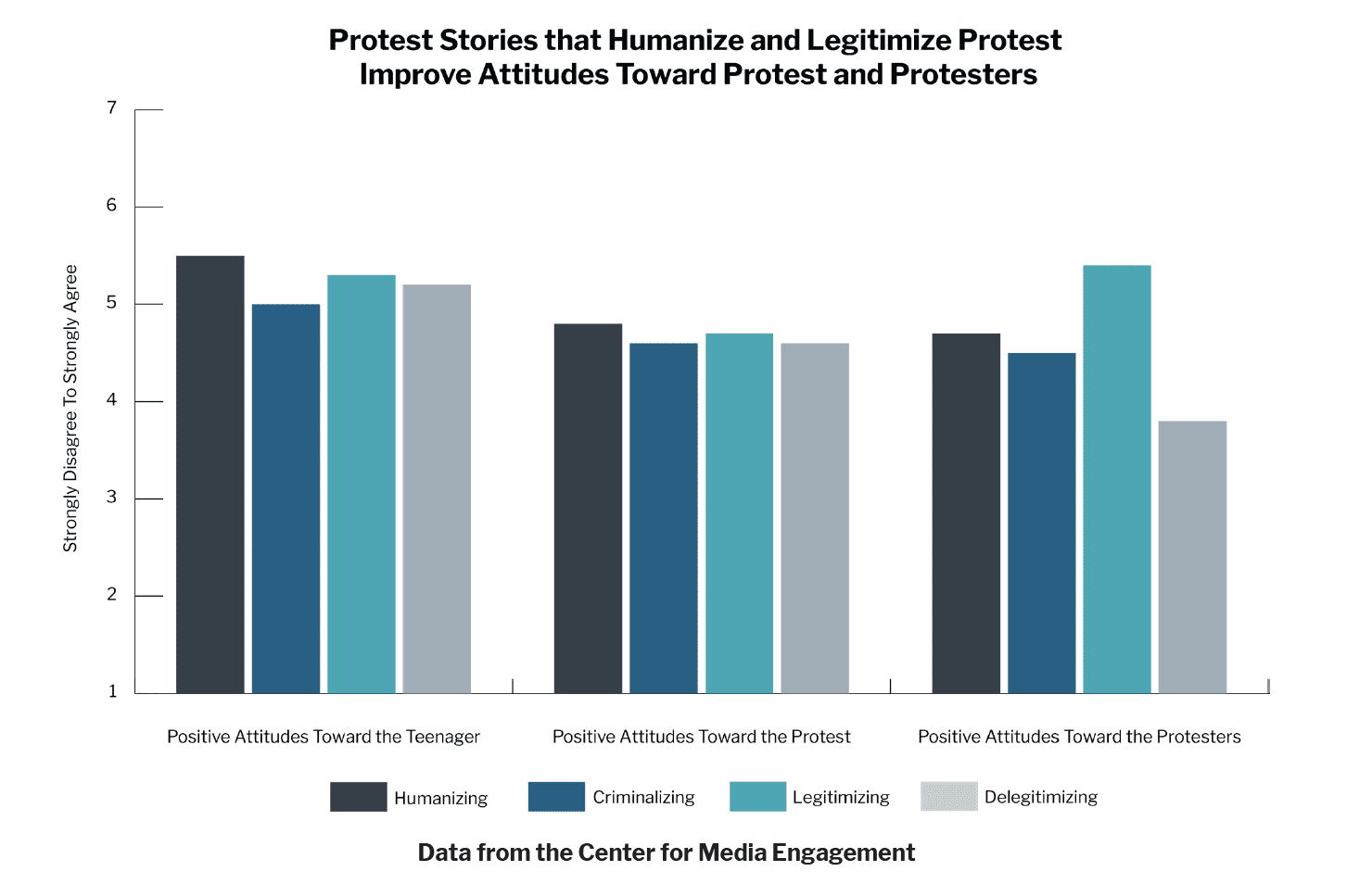

The stories that humanized the teenager whose death led to the protest prompted more positive attitudes toward the teenager,5 the protest itself,6 and the protesters.7 Stories told in a legitimizing way led to more positive attitudes toward the protest and the protesters but had no effect on attitudes toward the teenager who was the focus of the story. These results were consistent across both topics (Black Lives Matter and immigration) and held up regardless of participants’ political beliefs.

We also examined what effect telling protest stories in a humanizing and legitimizing way would have on people’s perceptions of how credible the story was. Results differed based on political beliefs. For Democrats and those with Democrat-leaning views, seeing a story told in a humanizing way increased their perception that the story was credible. But the opposite happened with those with Republican and Republican-leaning views. They viewed the story as less credible if it was told in a humanizing way.8 Whether a story was told in a legitimizing or delegitimizing way had no effect on credibility perceptions.

METHODOLOGY

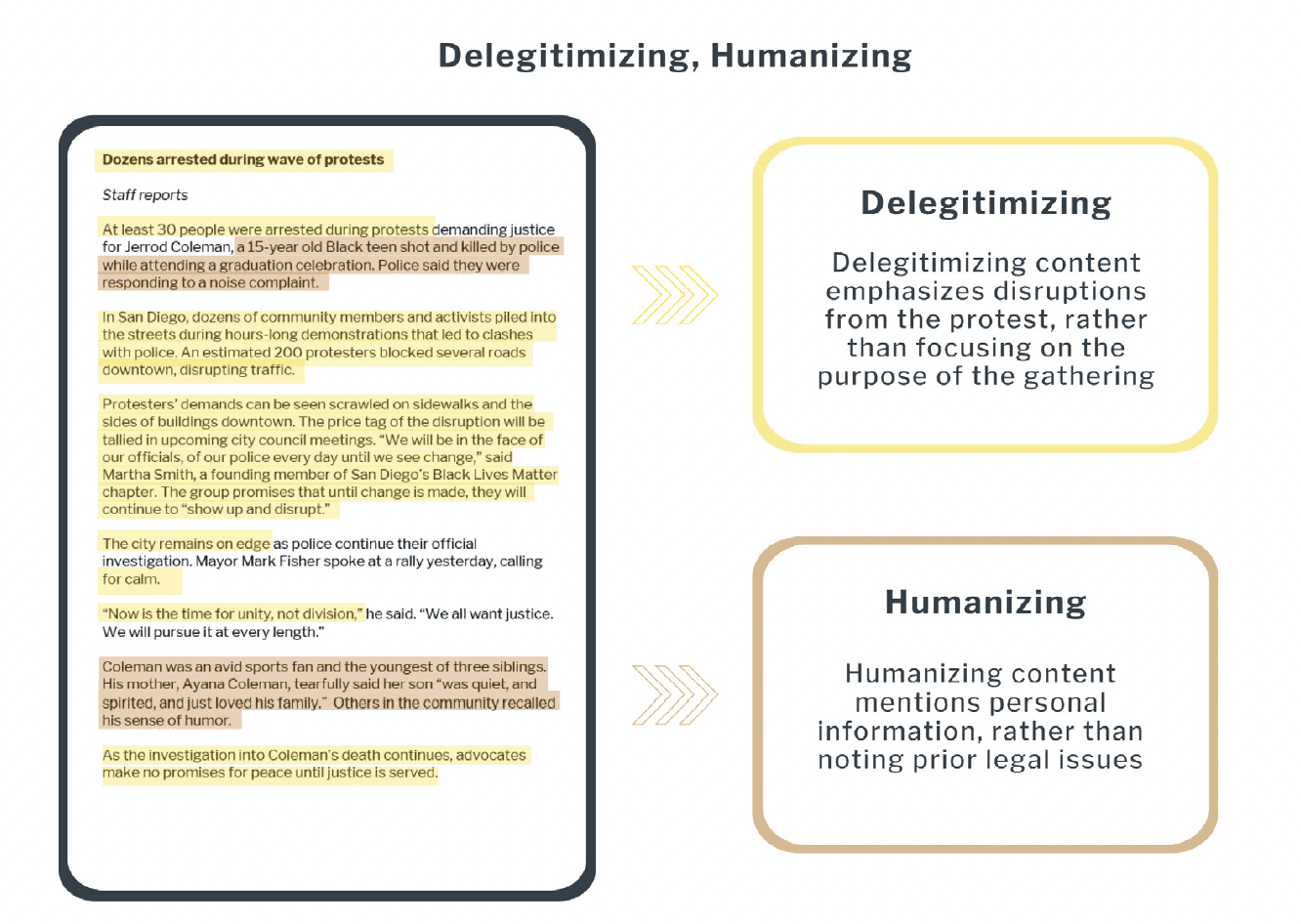

Our 1,5069 participants were recruited through CloudResearch, which draws participants from Amazon Mechanical Turk. Participants had to be at least 18 years old and live in the United States. We set up quotas to ensure we would recruit roughly half participants who are Democrats or have Democrat-leaning views and half who are Republican or have Republican-leaning views. This was neither a random nor a representative sample.

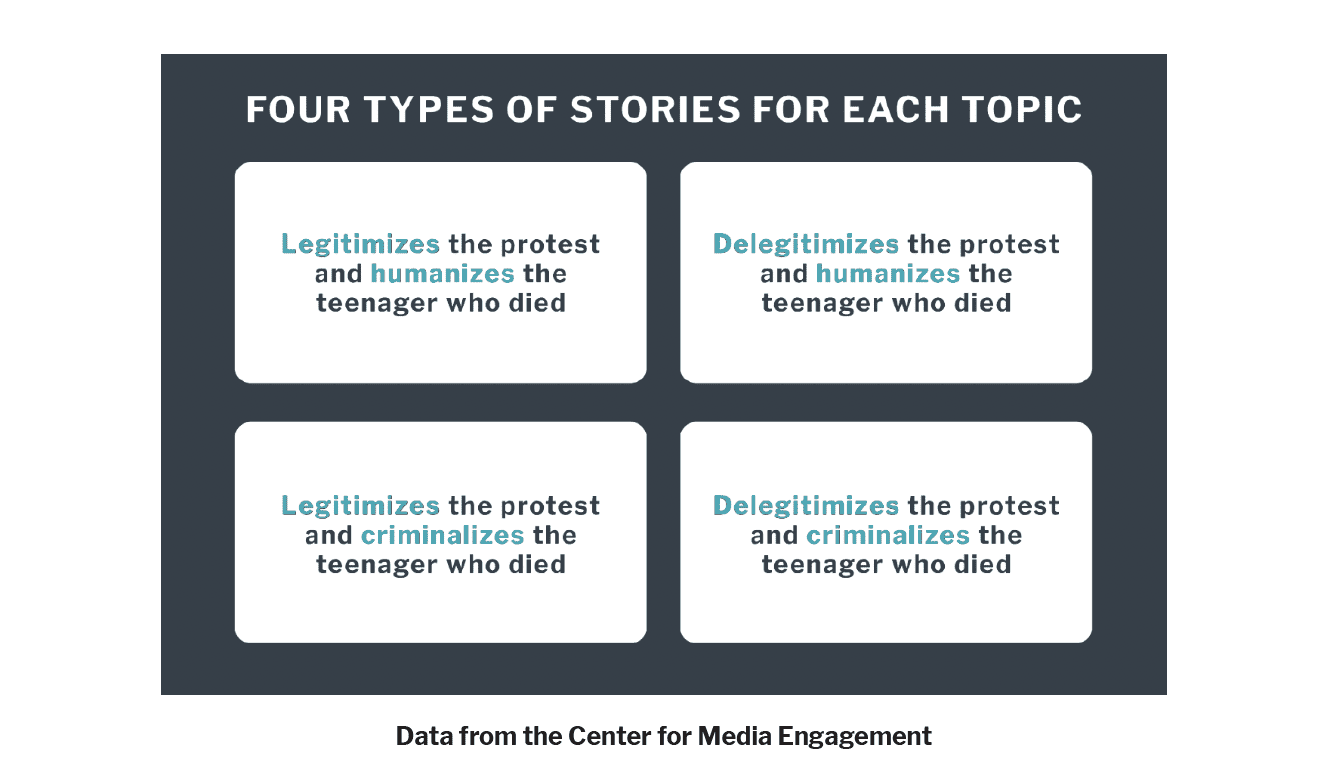

After consenting,10 participants were randomly assigned to view a news story about a protest involving an underrepresented group. They either saw a news story about a Black Lives Matter protest after a Black teenager was shot by police or a news story about a protest after a Latin American immigrant teenager was killed at a migrant detention center.

Additionally, participants were randomly assigned to view a story that either legitimized or delegitimized the protest and that either humanized or criminalized the teenager whose death spurred the protest. Multiple parts of the story were changed to reflect the different types of stories for each topic.

The news stories were adapted from real news stories about actual events but were edited for length, clarity, and to fit the experimental conditions.11 Two topics were used to examine robustness of results across topics, not because specific differences were predicted.

The stories were all posted on The Gazette-Star, a mock news site we created. All stories had a “staff reports” byline, and a functional “like” button, although almost no participants clicked it.

We kept story details as consistent across topics as possible so they were comparable. Text was added to stories to reflect the experimental conditions (legitimizing versus delegitimizing and humanizing versus criminalizing). This content was consistent across topics. To help ensure people read the stories, the stories were short (roughly 300 words each), the survey was designed so that people could not advance past the story they were to read for 5 seconds, and participants who could not see the story or indicated they failed to read the story were screened out.

After viewing the news story, participants answered questions about their attitudes toward the teenager in the story whose death spurred the protest, the protest itself, the protesters, and their perceptions of how credible the news story was.

SUGGESTED CITATION:

Masullo, G.M., Brown, D.K., and Harlow, S. (October, 2021). A better way to tell protest stories. Center for Media Engagement. https://mediaengagement.org/research/a-better-way-to-tell-protest-stories

- Chan, J. M., & Lee, C. C. (1984). The journalistic paradigm on civil protests: A case study of Hong Kong. In A. Arno & W. Dissanayake (Eds.), The news media in national and international conflict (pp. 183–202). Westview; Gitlin, G. (1980). The whole world is watching. University of California Press; McLeod, D. M., & Hertog, J. K. (1992). The manufacture of “public opinion” by reporters: Informal cues for public perceptions of protest groups. Discourse & Society, 3(3), 259–275. https://doi.org/10.1177/0957926592003003001; Shoemaker, P.J. (1982). The perceived legitimacy of deviant political groups: Two experiments in media effects. Communication Research, 9(2), 249-186. [↩]

- Harlow, S., & Kilgo, D. K. (2021). Protest news and Facebook engagement: How the hierarchy of social struggle Is rebuilt on social media. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 10776990211017243; Kilgo, D. K., & Harlow, S. (2019). Protests, media coverage, and a hierarchy of social struggle. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 24(4), 508-530. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161219853517. [↩]

- Kilgo, D. K. (2021). Police violence and protests: Digital media maintenance of racism, protest repression, and the status quo. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 65(1), 157-176. [↩]

- This assertion stems from the protest paradigm, which has found that systemic biases built into journalistic routines tend to delegitimize and marginalize social movements. See Harlow, S., & Kilgo, D. K. (2020). Perceptions versus performance: How routines, norms, and values influence journalists’ protest coverage decisions. Journalism, Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884920983058. [↩]

- This was measured using six statements on a 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) scale. These were: “(The teenager) was a criminal,” “(The teenager) was responsible for his own death,” “Police were responsible for (the teenager’s) death,” “The (teenager’s family) deserves justice,” “(The teenager) was too young to die,” and “(Black Lives Matter/Immigration) protests are warranted.” The name of the teenager or the protest was inserted into the question for the appropriate condition. The first two statements were reverse scored, so that for all statements a higher number indicated more positive attitudes. The statements were averaged into an index, M = 5.30, SD = 1.27, Cronbach’s α = 0.85. This index was the dependent variable for a multi-factorial ANOVA with both humanizing/ criminalizing and legitimizing/delegitimizing as independent variables. A main effect was found for humanizing, F (1, 1340) = 79.27, p < .001, η2 = 0.04, but not for legitimizing, F (1, 1340) = 0.19, p = .66, η2 = 0.00. This model and all other models reported in this study included income and education as covariates because a random assignment test showed that one income group and one education group were slightly over-represented in one manipulated condition. Political beliefs was also used as covariate given the partisan divide regarding attitudes toward race and immigration. See Doherty, C., Kiley, J. & Johnson, B. (2017, October). The partisan divide on political values grows even wider, Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2017/10/05/4-race-immigration-and-discrimination/ [↩]

- This was measured using four statements on a 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) scale. These were: “The protests were a waste of time,” “There was a legitimate reason to protest,” “More protests are needed to achieve justice,” and “The protests don’t accomplish anything.” The first and fourth statements were reverse scored, so for all statements, a higher number indicated a more positive attitude toward protest. These were averaged together into an index, M = 4.74, SD = 1.69, Cronbach’s α = 0.92. This index was the dependent variable for a multi-factorial ANOVA with both humanizing/criminalizing and legitimizing/delegitimizing as independent variables. A main effect was found for both humanizing, F (1, 1340) = 7.74, p = .01, η2 = 0.003, and legitimizing, F (1, 1340) = 5.62, p = .02, η2 = 0.002. [↩]

- This was measured using three statements on a 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) scale from Mourão, R. R., & Kilgo, D. K. (2021). Black Lives Matter coverage: How protest news frames and attitudinal change affect social media engagement. Digital Journalism, Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2021.1931 900. These were: “Protesters were out of line,” “Protesters were violent,” and “Protesters helped initiate conflict.” The items were reversed scored so that a higher number indicated more positive attitudes toward protesters and averaged into an index, M = 4.67, SD = 1.81, Cronbach’s α = 0.92. This index was the dependent variable in a multi-factorial ANOVA with both humanizing/criminalizing and legitimizing/delegitimizing as independent variables. A main effect was found for both humanizing, F (1, 1335) = 3.78, p = .05, η2 = 0.002, and legitimizing, F (1, 1335) = 499.55, p < .001, η2 = 0.21.[↩]

- This was measured using a scale from Appelman, A., & Sundar, S. S. (2016). Measuring message credibility: Construction and validation of an exclusive scale. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 93(1), 59–79. On a 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) scale, participants rated how “authentic,” “accurate,” “believable,” and “trustworthy” the story was. Scores were averaged together into an index, M = 5.01 SD = 1.27, Cronbach’s α = 0.91. This index was the dependent variable in a multi-factorial ANOVA with both humanizing/criminalizing and legitimizing/delegitimizing as independent variables. A significant interaction effect, F (1, 1339) = 30.87, p < .001, η2 = 0.02, was found for political beliefs and humanizing, although no significant main or interaction effects were found for legitimizing. A Sidak adjustment showed that story credibility perceptions for Democrats and Democrat-leaning participants were significantly higher when exposed to the humanizing story, compared to the criminalizing story. The same test showed that story credibility perceptions for Republicans and Republican-leaning participants were significantly lower when exposed to the humanizing story, compared to the criminalizing story. [↩]

- Initially, 1,623 people started the survey, but data were removed for those who sped through the survey (n = 56), indicated they could not see the news story that was the experiment stimulus (n = 29), may have taken the survey more than once (n = 24), failed at least one of three attention checks embedded in the survey (n = 6), did not indicate they were at least 18 years old (n = 1), and indicated they did not read the provided news story that was the experimental stimulus (n = 1), resulting in N = 1,506. [↩]

- The Institutional Review Board at The University of Texas at Austin approved the project June 24, 2021. [↩]

- The stories used in this experiment were adapted from exemplars that appeared in previous content analyses of immigration and anti-Black racism protests stories that appeared in local and national newspaper coverage. [↩]