Terms like “fake news” dominated early discussions of problematic false content circulating online. As academics, policymakers, and industry professionals addressed the issue – and social media platforms allowed the public to identify “false news” on their feeds – researchers reiterated the importance of using alternative phrases such as “misinformation.” This project explores why this language matters and how some of the most common terms for false content affect public perceptions of journalists and news media.

Our results offer two main suggestions for news organizations:

- Use the term “misinformation” in your reporting

Compared to “false news” or “fake news,” using the term “misinformation” improves journalists’ perceived credibility. - Stop using the term “fake news” entirely

Using “fake news” in reporting decreases trust in the news organization using the term.

Additionally, we found that when politicians used the term “fake news” in a tweet aimed at a news outlet, it hurt trust in the news organization and in the credibility of its journalists more than when a news organization used the term. Given this, we recommend that newsrooms emphasize the journalist-reader relationship in ways that can build trust in their outlet and lessen the chance that attacks from political elites could damage those relationships.

For a more in-depth write-up of these studies, please see our recent peer-reviewed article in the Journal of Applied Communication Research.

Testing the Ways We Discuss False Content

This study considered three commonly used phrases for false content: fake news, false news, and misinformation. We anticipated that the effects of each phrase on audience trust might vary in two distinct circumstances. In the first, specific labels like “fake news” might lead people to associate the term more negatively with liberal-leaning news outlets like The New York Times as this description, or insult, has frequently been leveled in reference to such newsrooms. In the second case, because false content is associated with partisan cues, labels might be more influential when coming from a politician compared to when they are used by a news organization. We conducted two studies that measured how each of the three phrases for describing false content – fake news, false news, and misinformation – influenced peoples’ levels of trust in media in general, their trust in the specific news organizations, and the credibility of journalists working at those news organizations in these two circumstances.1

Does How We Talk about False Content Matter for Right- or Left-Leaning Media Organizations?

In our first study, we showed participants a set of tweets with stories originating from either a conservative-leaning news outlet (The Wall Street Journal) or a liberal-leaning news outlet (The New York Times) and randomly varied the phrases for false content (fake news, false news, or misinformation). Then, we measured participants’ media trust in general, their trust in the news outlet cited in the tweets, and how they felt about the credibility of the journalists from that outlet.

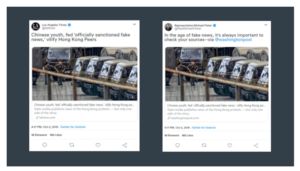

Example Tweets from a News Outlet

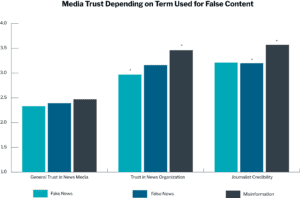

The results from this experiment produced four key takeaways:

- Using the phrase “fake news” did not affect media trust in general, regardless of whether people saw the term appear in tweets citing a right-leaning or left-leaning source

- People who saw the phrase “fake news” reported lower trust in the specific news organization referenced in the tweets (either The Wall Street Journal or The New York Times) compared to people who saw tweets using the term “misinformation”

- People who saw the term “fake news” or “false news” reported the outlet’s journalists as significantly less credible than people who saw the term “misinformation”

- There were no differences in any of the trust or credibility measures based on whether the tweets referred to right- or left-leaning outlets (either The Wall Street Journal or The New York Times)

Do Terms for False Content Affect Media Trust More When Used by a News Organization Or by a Politician?

In our second study, we showed participants a set of tweets originating from either a fictional politician or Los Angeles Times. We randomly varied the phrases for false content used in these tweets (fake news, false news, misinformation – or a control group that saw no tweets).3 Then, we measured participants’ media trust in general, their trust in Los Angeles Times, and how they felt about the credibility of journalists at Los Angeles Times.

Example Tweets from a News Organization and a Politician

The results from this experiment produced several key takeaways:

- Using the phrase “fake news” did not influence media trust in general, regardless of whether people saw a politician or a news organization use the term

- There were no differences in trust for Los Angeles Times or its journalists if they used fake news, false news, or misinformation in their tweets

- Compared to those who saw Los Angeles Times use the phrase “fake news,” people who saw a fictional politician use the phrase “fake news” reported lower trust in Los Angeles Times and perceived their journalists to be less credible

What Our Research Means for Discussions of False Content

Our research produced several important findings related to the importance of word choice when covering issues of false content.

First, “fake news” is a phrase that should be avoided. More so than “false news” or “misinformation, “fake news” consistently negatively affects media trust and journalist credibility. This seems especially consequential for the news organization using the term rather than for the media in general. Based on these findings, we suggest news organizations avoid the term even when using it as a strategic choice. For instance, some newsrooms have implemented advertising campaigns to distinguish themselves from the phrase “fake news” while simultaneously invoking the phrase itself (e.g., campaigns calling their journalism “real news”). Since association with the term can undermine audience trust, we recommend that newsrooms distance themselves from the term entirely.

Second, our results suggest that who is using the term may matter just as much if not more than the term itself. We found that the negative effects of these terms for false content are strengthened when used by a politician to describe a news story compared to when they are used by the news outlet itself. While we do not expect newsrooms to combat discourse from political elites, we do suggest newsrooms acknowledge that this discourse can negatively impact evaluations of their content and their journalists. Drawing from past work on incivility – of which accusations of “fake news” arguably qualify – we recommend that newsrooms emphasize the journalist-reader relationship in a way that can build trust in their outlet and lessen the chance that attacks from political elites could damage those relationships.

Thank you to the Hewlett Foundation and the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation for funding this report.

- In this study, we focus on levels of media trust for the American public, but there are reasons to expect outcomes would be similar in other countries based on existing research. For example, see: Farhall, K., Carson, A., Wright, S., Gibbons, A., & Lukamto, W. (2019). Political elites’ use of fake news discourse across communications platforms. International Journal of Communication, 13, 4353-4375.[↩]

- Media trust in general was measured by asking participants, ‘How much of the time do you think you can trust media organizations to report the news fairly?’ with response options of just about always (1) to none of the time (4). Responses were reverse-coded so higher values indicated more trust in media. For media trust in specific news organizations, participants were asked to rate whether the news outlet they saw tweets from: ‘are fair, tell the whole story, are accurate, can be trusted’ on a scale from always true (1) to almost never true (5). For both outlets, we took the mean of the four items (NYT: M = 3.31, SD = 1.00, Cronbach’s α = 0.96; WSJ: M = 3.09, SD = 1.00, Cronbach’s α = 0.95). For journalist credibility, participants were asked three items about journalists at either The New York Times or The Wall Street Journal. Participants were asked to evaluate how true statements were that journalists (1) express criticism in an adequate manner, (2) have well-founded opinions, and (3) have well-reflected conclusions. Items were averaged (NYT: M = 3.25, SD = 0.91, Cronbach’s α = 0.90; WSJ: M = 3.40, SD = 0.94, Cronbach’s α = 0.91).[↩]

- We chose to include a control group in Study 2 in order to determine if exposure to any tweets at all, beyond just those referencing fake news/false news/misinformation, would affect participants’ media trust and/or trust in the specific news organization. [↩]