Multiple-Choice Quizzes Improve People’s Recall of Fact Check Details, but Don’t Reduce Belief in Misinformation

Fact-checkers face the difficult challenge of trying to get readers to retain key bits of information from fact checks while also helping them identify whether a claim is true or false. Online multiple-choice quizzes present an opportunity to encourage readers of a fact-checking article to engage with the content and to help them learn. Previous work from the Center for Media Engagement found that quizzes can improve the time people spend reading news and their political knowledge.

In this project, we investigated whether interactive quizzes can be used by fact-checkers as a tool to improve readers’ recall of key details of an article and to help people make decisions about the accuracy of fact-checked claims. We found that multiple-choice quizzes were effective at improving recall (even if quizzed on the details a week later), but they did not lead to changes in whether people thought the claim from the fact check was true or false.

The findings suggest that quizzes may be a useful tool for newsrooms and fact-checking organizations to assess the effectiveness of fact check articles and to determine whether readers are retaining the most useful and important pieces of information. Additional research is needed to see if these gains in knowledge aid in helping audiences come to more accurate conclusions in the long-term.

Study Details

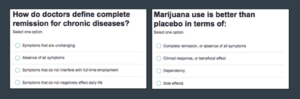

We conducted three studies that addressed various circumstances where fact checks might benefit from being accompanied by a multiple-choice quiz. Our online experiments measured how the presence of a multiple-choice quiz, either before or after a fact check, influences peoples’ recall of key pieces of information from the fact check and their ability to accurately identify claims as true or false.

Can Quizzing Before or After a Fact Check Improve Recall and Accuracy?

In the first study, participants were shown one of two fact check articles about a piece of health misinformation. Each of the claims in the articles were false. The first article debunked the notion that marijuana could cure Crohn’s disease. The second article debunked the rumor that women retain DNA from every man they have slept with.

We randomly varied whether participants saw a quiz before the fact check, a quiz after the fact check, or a fact check with no quiz. We also randomly varied whether participants answered questions about the fact check immediately after or one week after reading the article. Open-ended questions were used to measure how well people remembered key information from the fact check.

The results from this experiment produced three key takeaways:

- Multiple-choice quizzes helped readers recall specific details from the fact check.

- Even one week later, people were more likely to recall details from the fact check if they were quizzed before or after reading it.

- Multiple-choice quizzes did not help readers accurately identify a false claim.

Can Quizzing People on the Debunked Claim Itself Improve Recall and Accuracy?

Our second study used the same health misinformation as the first. We randomly varied whether participants read either a fact check by itself, or a fact check accompanied by two multiple-choice quiz questions. As in the first study, we also randomly varied whether participants answered questions about the fact check immediately after or one week after reading the article. Open-ended questions were used to measure how well people remembered key information from the fact check, but in this study, we tailored the questions to be more directly related to the false claim.

The results from this experiment produced takeaways that align with those from the first study:

- Multiple-choice quizzes helped readers recall specific details from the fact check.

- Even one week later, people were more likely to recall details from the fact check if they were quizzed after reading it.

- Multiple-choice quizzes did not help readers accurately identify a false claim.

Can Quizzing People on True or False Claims Improve Recall and Accuracy?

Our third study set out to understand what conditions might be necessary for multiple-choice quizzes to reduce belief in misinformation. This study included both true and false claims for participants to read and evaluate. We also used political misinformation to extend our findings beyond health misinformation.

Participants were shown a series of four fact checks. We randomly varied whether they received a two-question multiple-choice quiz after reading each fact check or received no quiz at all. All participants were contacted one week later to answer questions about the fact check and to rate the accuracy of the claims from the fact checks.

Despite incorporating additional contexts, the results from this experiment echo the takeaways from the first two studies:

- Multiple-choice quizzes improved participants’ recall of details from the fact checks.

- Even one week later, people were more likely to recall details from the fact check if they were quizzed after reading it.

- Multiple-choice quizzes did not help readers accurately identify true or false claims.

What Our Research Means for Fact-Checkers

Our research produced several important findings for fact-checking organizations and newsrooms implementing their own fact checks.

First, multiple-choice quizzes present a useful tool for fact-checkers aiming to improve peoples’ recall of the key details of a fact check. This finding seems especially useful for fact-checkers tasked with debunking complex topics like health or politics. Across three studies, we found that peoples’ recall of complex details from fact checks, such as “what is the blood-brain barrier,” improved after receiving a quiz with the debunked claim. This effect lasted even when measured one week later. We recommend that fact-checkers consider implementing quizzes as a means of helping the public digest and recall fact-checked information.

Second, multiple-choice quizzes are not a remedy for misinformation. Despite finding that quizzes aid in recall, we did not find that they are effective at changing peoples’ beliefs about whether a claim is true or false. Understandably, getting people to change their minds is a tall order that cannot be solved with a quiz alone. Based on this finding, we still encourage fact-checking organizations and newsrooms to implement multiple-choice quizzes but acknowledge that they do have limitations.

For a more in-depth write-up of these studies, please see our recent article in the peer-reviewed academic journal, Cognitive Research: Principles & Implications.

Thank you to Democracy Fund, the William & Flora Hewlett Foundation, and the Reboot Foundation for funding this research.