Stopping the spread of misinformation on Facebook is a difficult proposition. One of the reasons it is so difficult, particularly in the United States, is high levels of political polarization. Center for Media Engagement research shows that Democrats and Republicans are susceptible to believing misinformation about candidates from the opposing party and that Democrats and Republicans respond differently to fact checks.

Our results offer some strategies for employing fact checks effectively. First, utilizing strong language is important. We found that an early Facebook attempt to label misinformation as “disputed” is ineffective compared to the stronger label of “false,” which reduced misperceptions among Democrats. Second, our analysis demonstrated that providing context about the fact-checker can help to increase the effectiveness of a fact check. A random set of study participants were shown fact checks accompanied only by the name of the fact-checking source. Another random set of participants were shown the name of the fact-checking source and the source’s tag line, such as PolitiFact’s “Sorting out the truth in politics.” Fact checks accompanied by a tagline were more effective at correcting misperceptions for Republicans than fact checks without a tagline.

For a more in-depth write-up of these studies, please see our recent article that appears in the peer-reviewed academic journal New Media & Society.

Testing Fact Checks on Facebook

To understand how people react to political fact checks, the Center for Media Engagement built a mock Facebook News Feed that allows study participants to Like, Share, or Comment on posts (actions that could only be seen by us). The mock News Feed displayed five news articles – one of which was our crafted piece of misinformation. In both studies, the misinformation was targeted at either Donald Trump or Hillary Clinton.

Misinformation Labels

Our first study tested Facebook’s previous approach to fighting misinformation – a “disputed” label attached to articles that fact-checkers deemed misinformation – and compared it to a bolder label of “false.” We randomly altered the language of the fact check (either “disputed”, “false”, or the control which had no label) and later assessed participants’ belief in the topic of the misinformation.

There were three main takeaways:

- Democrats and Republicans believed misinformation targeted toward their political opponent more than misinformation targeted at like-minded political figures.

- The “disputed” label was not effective in correcting Democrats or Republicans about misinformation targeted toward their opponents.

- The “false” label was effective in correcting Democrats but not Republicans.

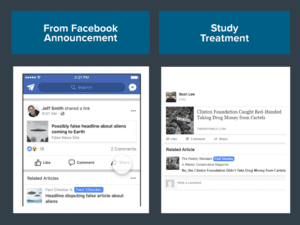

Mock Newsfeed Images for Study 1

Adding Fact Check Source Information

Our second study tested Facebook’s next attempt at correcting misinformation – including fact-check information as “related articles” underneath a misinformation post. Some participants were shown articles that only mentioned the source of the fact check and others were shown the source as well as a short tagline about the source. We also included a control with no fact check.

The symmetric partisan effects were confirmed – both Republicans and Democrats believed the misinformation about their opponents. We also learned two additional points:

- Changing the source of the fact check didn’t meaningfully alter the results, but, in some cases, including more information about the source did increase the effectiveness of the fact check.

- Republicans, when given a tagline about the fact-checking source, corrected their misbeliefs about their opponent more than Republicans who didn’t see a fact check.

Mock Newsfeed Images for Study 2

The source of the fact check was either PolitiFact, a state and national fact-checking organization, or Weekly Standard, a conservative opinion magazine. Both are part of the International Fact-Checking Network, which verifies those agreeing to a code of principles.

What our research tells us about fact-checking on Facebook

These findings translate into two primary points related to fact-checking on Facebook. First, whether you are a Democrat or a Republican (and likely if you’re something else too), we are all motivated to believe what we want to believe. This kind of motivated reasoning encourages people to believe misinformation about their opponent at higher rates than they would believe misinformation about their preferred candidates.

Second, fact-checking efforts did reduce misperceptions for Democrats and Republicans in some circumstances. For this reason, we encourage fact-checkers and social media companies to think about best practices for providing corrective information. Keep in mind that effective strategies may not always be the same for both groups. In our study, we found that simply giving a little more information about the fact-checking source was helpful for correcting misperceptions among Republicans and blunt statements about the factuality of a statement were helpful among Democrats. We encourage other researchers – both in the academy and in the field – to continue experimenting with ways to sweeten the bitter pill of corrective information.

Thank you to The Annenberg Public Policy Center and The William and Flora Hewlett Foundation for funding this study.