Introduction

Group identity has the potential to be a strong political motivator. The political position a person takes on an issue, or which party they choose to vote for, can be affected by the norms or attitudes of the group memberships they hold. Political elites have long recognized this potentially powerful and evolving correlation. So too have propagandists. Oftentimes, they are one and the same.

Political elites and their proxies who deploy propaganda campaigns may seek to exacerbate existing social tensions between identity groups: ethnic, racial, economic, gendered, sexual orientation, and more. This includes the manipulation of social orders through the demeaning, rejection, or desirability of identity groups in pursuit of political objectives, otherwise known as identity propaganda. In modern election seasons, political elites and allies wield identity propaganda and divisive rhetoric on social media to grant and deny legitimacy to select political voices based on identity.

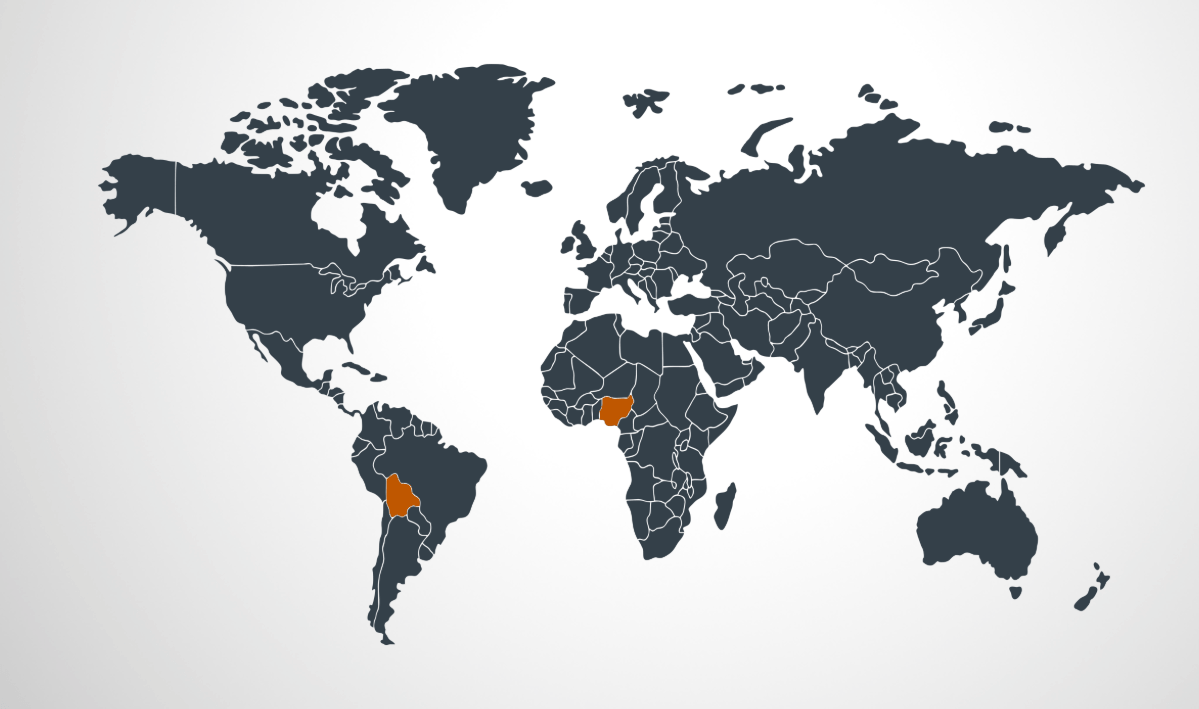

The Center for Media Engagement sought to understand how political, elite-led identity propaganda played a role in recent Bolivian and Nigerian elections.1 We interviewed journalists, digital rights activists, civil society workers, government employees, and more to better understand how identity-driven propaganda unfolds on social media spaces and how this leads to an exclusionary nationalism that pits ethnic groups against each other.

Why Bolivia and Nigeria?

Bolivia and Nigeria exemplify democratic backsliding, which emphasizes the ebbs and flows of democratic emergence and recession. This is demonstrated through their wide array of political systems and actors including guerilla strongmen, military dictatorships, constitutional dictatorships, parliamentary democracy, and most recently American-style Presidential democratic setups.

Both countries also recently experienced presidential elections with tumultuous campaign seasons and contested results. Bolivia’s former MAS party leader, Evo Morales, was disqualified from taking office after a contested 2019 election, resulting in an interim government and followed by a victory for MAS leader Luis Arce in the 2020 reelection. Nigeria’s heated 2023 presidential election resulted in an APC victory for Bola Tinubu that was reinforced after it was taken to the Supreme Court later that year.

Each country also has a history of colonialism and independence. The sixteenth century Spanish conquest of Bolivia left lasting economic, geographical, and political divides between ethnic populations, while British colonial rule in Nigeria strategically reinforced ethnic-religious geographical and political tensions that may be seen in today’s politics.

Lastly, political violence continues to permeate Bolivian and Nigerian elections in the form of violent assault, voter suppression, and state-led violence against protestors.

Identity Propaganda in Bolivia and Nigeria

Political propaganda campaigns aim to exacerbate tensions that already exist in society. Our interviewees spoke of the role of ethnicity and religiosity – and their connections to class and geography – in their countries and how they interplay with politics during elections. In election propaganda, these factors present as an ‘us’ and ‘them’ mentality that emphasizes inclusion or exclusion of group membership. This includes dichotomies of ‘urban (indigenous populations) vs. rural (white populations)’ in Bolivia and ‘North (Muslim populations) vs. South (Christian populations)’ in Nigeria.

These ‘us versus them’ narratives became campaign issues related to political rights and representation in government. Communication consultant and sociologist Rafael spoke of Evo Morales’ political legacy as the first elected indigenous President of Bolivia. He said that Spanish-descendant Bolivians realized a kind of “consciousness” after the election of an indigenous President and learned that their country was not just their “own” but also a place “to share political power, or economic power” with indigenous populations. However, this realization that the country was a shared and equal place for Spanish-descendant and Indigenous Bolivians became a politically charged issue enmeshed in racist rhetoric. Rafael pointed out that political actors on both sides began to use this heightened ethnic tension as a “tool” in order to accumulate political power. This identity propaganda that focuses on ethnic divides only works against all the progress and processes that have been established within governance fighting for indigenous rights in Bolivia, according to Strategy Manager in Vice Ministry of Communications Laura.

This kind of propaganda is far from a new political tactic. While it has evolved in terms of popularity and scale, its use in Nigeria was described as natural to the political systems. Nigerian fact-checker and disinformation researcher Silas framed the deployment of identity propaganda as “not particularly [done] intentionally” but rather as a communication strategy “informed” by these ethnic and religious divides. He commented that local communities like to vote for a member of their own tribe. So, the political opposition is naturally going to attack that tribal credibility to undermine their opponent.

Identity-centered propaganda continues to conflate ‘ethnicity’ and ‘qualification’ within the political spheres in Bolivia and Nigeria. Nigerian public relations consultant Jonathan spoke to this pattern when he said, “Nigeria is a country with over 300 ethnic groups… Which means that our unity is very fragile, right, cause overtime leadership failure has led to, you know, high level of suspicions by the different ethnic groups.”

The Role of Social Media

Identity-centric propaganda continues to transition from offline, traditional realms to digital ones. Digital realms allow these kinds of campaigns to reach greater numbers of people, in disparate geographies, across demographics, in milliseconds. While social media does not create identity-driven propaganda campaigns, it does help optimize them. It also, noted Bolivian policy analyst Jan, helps the “normalization of dehumanization discourse” both on and offline.

This ‘mainstreaming’ or ‘normalization’ of hate through identity propaganda is helped by political elites and allies partaking in propaganda campaigns and perpetuating the content to their followers on social media (or hiring third parties to spread it for them). Legal aid to an opposition senator Carolina spoke of the divisive speech and identity propaganda that exists among Bolivian leadership across the political spectrum, “…our leaders, instead of trying to, you know, heal these [divides], they’re trying to use it to keep us divided and fight each other.”

Another top-down way to spread identity propaganda online is through political influencers on social media, which shields political candidates from the accountability of spreading potentially hateful or discriminatory speech. These influencers can be directly hired or, in many cases, operate through a third-party marketing or PR consultancy. Legal practitioner Khadijah spoke of Nigerian political parties’ use of both mega-influencers (influencers with millions of followers) and micro-influencers (influencers with a smaller but more niche following) within political campaigning. Journalist David also commented on the use of political influencers, saying, “It’s very transactional. There’s no ideology behind it, so, as far as the influences go: pay me, pay me! Here’s my race card. Pay me, and I’ll Tweet whatever you want me to, so I’ll post whatever you want me to.”

Another tactic is the use of bots. In Bolivia, Rafael noted that automated accounts interjected narratives related to the inter-ethnic political violence that resulted in the contested 2019 and 2020 elections. He said these bots:

“…were trying to undermine the credibility of the Chamber and the results…those bots who were in Miami were spreading lies against the indigenous, and some others were in Caracas, in Venezuela, and those ones were spreading the fake news about the about the non-indigenous [and], non-whites.”

Nigerian journalist and fact checker Niyi also pointed towards the importance of religious endorsements within Nigeria politics and the presence of propaganda campaigns meant to confuse or discredit these endorsements, both off and on social media. Journalist Victoria emphasized the powerful impact in Nigeria – a very religious but not necessarily pious country in her view – as she said, “religious leaders are strong opinion leaders, and…they are actually a very good conduits to spread any kind of information.”

Political Consequences

Identity propaganda campaigns within electoral processes worsen structural inequalities, such as socio-economic cleavages of ethnicity, religion, and class. This can present problems establishing a collective identity based on civic collectiveness (which stresses inclusivity based on shared political values). Rather, identity propaganda promotes an ethnic nationalism that highlights belonging or dis-belonging based on ethnicity and relation to a particular place. This can create an exclusionary framework that divides majority and minority populations into ‘us’ versus ‘them,’ further justifying subjugation of one population over the other. The political question then becomes: which groups get to be included and excluded within the vision of a nation?

Propaganda from political elites and their allies reinforces these divides and attempts to link ethnic-group identity with political credibility/incredibility. This diminishes the inclusion and plurality of voices expected within liberal and representational democratic governance. Rather than setting the expectation that a political actor will serve a nation built on a civic-collectiveness, electoral political structures center around an exclusionary ethnic-collectiveness. Propaganda in Bolivia and Nigeria help this endeavor as actors curry partisan favor with a particular ethnic or ethnic-religious group by conflating political virtue and capability with ethnic identity, or by denigrating and denouncing a political actor based on their ethnic group.

Both Bolivian and Nigerian interviewees spoke of the growing importance of social media platforms as a space for reading, sharing, and creating political information. The public has crafted their own ‘public square’ where political movements can be mobilized, and political deliberation can occur. Yet, popular political actors, their spokespersons, or allied influencers spread identity propaganda that threatens this ‘public square’ by polluting the information environment with politically harmful, hurtful, and false information. Democratic deliberation and political participation by citizens on social media is being manipulated by political actors digging into and exposing deep-rooted societal divides. These efforts disrupt political discourse, deliberation, and participation within online spaces, which for many is a core deliberative and expressive daily practice.

It is also worth considering how increasing identity propaganda campaigns can threaten safe political discourse. Political elites and allies driving identity propaganda campaigns can fuel ethnic divides in already polarized and potentially violent political environments. This is highlighted through the polarized ethnic discourse and ongoing political violence within Nigeria’s 2023 elections and Bolivia’s 2019, 2020, and upcoming 2025 elections. In Nigeria, hundreds of people were arrested for violent or hostile acts; including destroying election materials, buying votes, and voter intimidation and threats. In Bolivia, 2019 and 2020 were marked with violent protests between anti-Morales (traditionally thought of as dominantly mestizo, white populations) and pro-Morales (traditionally, though not always, thought of as indigenous populations) demonstrators. The political violence stems from state forces that turned violent against protestors, killing twenty-three Bolivians on a single day in November 2019.

Ethnic, religious, and class tensions exacerbated by identity propaganda and accelerated through social media are increasingly problematic within Bolivian and Nigerian political and national landscapes. They weaken guarantees of safe, free, and fair elections, public political deliberation, expression, participation, and the expectation of credible and inclusive representational governance. Ultimately, the practice of identity propaganda may contribute to Bolivian and Nigerian democratic backsliding.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to acknowledge and thank former research assistant Dr. Zelly Martin and former undergraduate research assistants Angela Lim, Mirya Dila, Tanvi Prem, Meera Hatangadi, and Madison Esmailbeigi for their help with interviews.

This study is a project of the Center for Media Engagement at The University of Texas at Austin and is supported by the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, Omidyar Network, and Open Society Foundations.

- We conducted 33 semi-structured and in-depth interviews [Bolivia (15) and Nigeria (18)] via Zoom from October 2023 to May 2024.[↩]