Comments posted on online news stories and news organizations’ social media sites have become a ubiquitous part of journalism today. Hundreds or even thousands of comments are often posted in response to a single story, and all too often these comments are laced with personal attacks, profanity, insults, or name-calling. This project sought to understand how professional journalists – in print, broadcast, and web-only publications – deal with these comments.

To do so, we interviewed 34 professional journalists from a wide geographic area who are employed in a variety of journalistic jobs. Our sample included journalists with years of experience, as well as relative newcomers to the field. We analyzed their responses as a whole, looking for common experiences across the journalists we interviewed. Journalists are not identified by name to protect their privacy and encourage openness.

The main questions we sought to answer were:

- To what extent – if any – do you see reading comments posted on your news site or its social media pages as part of your job?

- To what extent – if any – do you moderate or manage uncivil comments by hiding or deleting them?

- To what extent – if any – do you engage with commenters by responding, pointing out errors, or providing new information?

Key Findings

The following results stand out:

- All the journalists interviewed reported that they at least occasionally read comments, although only some set aside a specific period of work time to do this.

- Some journalists had the power to moderate, hide, or delete comments, but others did not. They were mixed in how frequently they utilized this power.

- Two-thirds (66.7%) of the journalists reported responding to commenters at least occasionally, although most tried to steer clear of responding to uncivil comments.

- One third (33.3%) were strongly opposed to responding to comments in any manner, seeing it as outside their journalistic role.

Implications for Newsrooms

Our interviews suggest a shift toward journalists embracing commenting and seeing reading them – and sometimes responding to them – as a vital part of their jobs. Earlier studies have found that journalists had a more negative view of online comments.1 For example, a survey of 647 journalists at 36 news organizations found most did not read the comments.2 Similarly, interviews with journalists in two other studies reported a dim view of comments and little interaction between journalists and commenters.3

The journalists we interviewed viewed comments as a means to understand what their audience members are thinking, to improve their coverage with follow-up stories, and to engage with their readers. A few reported that engaging with readers was essential to driving traffic to their sites, so they saw responding to comments as necessary for their news organizations’ survival.

However, our interviews also suggest that journalists have some ambivalence about this new task. Some embraced reading and responding to comments heartily, but others felt overwhelmed by how much time it took. Others saw responding to comments as outside of their journalistic duties, suggesting they could not continue as objective watchdogs of the public trust if they engaged with the audience.

In particular, journalists were cautious about responding to uncivil comments online for fear they might escalate the situation or because they were unsure what to say. Most said they steered clear of responding to uncivil comments, although a few offered strategies for calming the incivility. But they would back off if things began to escalate.

The Study

Reading Comments Posted on Stories is a Regular Part of the Job

All the journalists we interviewed reported reading comments, at least occasionally. Some embraced this task enthusiastically, seeing it as a necessary and welcome expansion of their duties. As a freelancer with 12 years’ experience described it: “I sometimes see the comments as the extra track on the album.” His thoughts were typical of other journalists who embraced the comments. He saw them as a place where he could see what his audience thought of his stories.

While not all the journalists were as enthusiastic, most saw reading the comments as an important means to see if they had made a mistake or to find suggestions for follow-up stories. “It’s a way of finding out much more immediately how your work is being received,” explained a newspaper reporter on the job since 1981.

However, just reading the comments can be exhausting or impossible because there are so many. A television journalist with three years’ experience said she sets aside 30 minutes daily to read comments, but she cannot even get through a third of the comments she wants to read in that time.

A journalist with 20 years’ experience who works at a web-only publication said she checks comments every couple of hours to see what the public is saying. The number of comments is too high for her to get through them all.

Sometimes the vitriol journalists see in the comment streams can lead them to give up even looking at comments. A journalist who works at a web-only publication recalled a story she did regarding the funeral of a newsmaker. It drew heated debate online and vicious attacks against her, claiming her report was biased. She started to read the comments, but it was too painful to continue. “I just shut the computer, closed Facebook, and said, ‘I done,’” she recalled.

Hiding, Masking, and Deleting Comments are Tools to Head Off Incivility

The journalists we interviewed varied on whether they had the power to moderate, hide, or delete comments. Some journalists could do this at will. Others could only report or flag an offensive comment to a third party or an editor, who would then decide what to do. This delay could lead to frustration as the journalists waited for a nasty comment to be removed.

Those journalists with the power to manage comments directly reported that they used it as a means to control the conversation and head off incivility before it escalated. Hiding or masking comments, in particular, was a useful method, the journalists said, to remove a comment that seemed to bait other people. For example, the TV journalist with three years’ experience said she watches for incendiary comments and tries to mask them before others see them and react. An example of the type of comment she might mask is: “I hate Obama.” “I can see where it’s about to get ugly, but it’s not ugly there yet,” she said.

However, a newspaper reporter with eight years’ experience takes an opposite approach. She can flag offensive comments, and moderators at her news organization will remove them. But she chooses to never do this.

“People aren’t stupid. If people put a bunch of vitriolic nonsense on a comment board and they are swearing. … Everyone who can read that comment can see that comment for what it is,” she explained. “I would probably leave these comments there and let people see them for what they are.”

Other journalists said they generally spiked a comment if it contained profanity or personal attacks, but some name-calling would be allowed to give the public freedom to speak out. “I think people like to argue with other people,” said a newspaper social media editor with three years’ experience. “I think it’s kind of a really fine balance. I think you have to know when to delete and not to delete.”

A newspaper reporter who is not allowed to delete comments directly said he frequently flags them, so a moderator will delete them to maintain the publication’s brand. “A lot of times you see F***. If I see it, I’ll flag it. I’m a bit of a flagger. It’s a website that we control, and we shouldn’t allow it. We wouldn’t allow it in print,” said the journalist, who has 35 years’ experience.

Some journalists worried that deleting any comment would lead to complaints from readers about unfairness, so they tended to leave all of them up. “I never delete even an uncivil comment. It’s freedom of expression and deleting is sort of censorship,” said a wire service reporter with 30 years’ experience.

Majority of Journalists Interviewed Saw Value in Engaging with Commenters

The majority of the journalists we interviewed reported that they believe it is part of their jobs to engage with commenters, at least occasionally. Engaging in comments may set a tone for the conversation, some of the journalists said, or make it less likely people will act inappropriately. But that works best if the public knows the journalist, said a newspaper journalist with 33 years’ experience.

“It helps when the people know the person who is monitoring,” she said. “If it’s a faceless organization monitoring, you get attacked for monitoring.” These findings add further validity to the previous Center for Media Engagement report which experimentally found that a recognizable journalist engaging in the comment section can improve the tone of the comments.4

Journalists said they considered talking to commenters as a way to connect with them and build community, as well as provide additional information on stories that may not have fit in the original report. “It’s a way of building readership,” explained the newspaper reporter with 35 years’ experience. “If you connect with your readers, they are more likely to come back.”

In fact, several journalists saw engaging with the audience as vital to the survival of their news organizations, which depend on page views for success. “We engage pretty frequently,” said a reporter for a web-only publication with 12 years’ experience. “We are a traffic-based enterprise, so it matters that we engage with our commentators.”

Another reporter with 10 years’ experience said he tries to respond to comments on all his stories, answering questions or even challenging readers politely when they write untruths. “It is an extension of your work to get in there and participate, “ he said. “It’s ugly and messy.” But he will stop short of getting into an argument. If he points out an inaccuracy in what a commenter has said, and the commenter attacks, he will back off.

Most of the journalists said they received little training on how to respond to commenters or what to say to calm incivility. The most they were told was to stay respectful and objective and not get emotional. Many of the journalists we interviewed felt unequipped to diffuse tension or incivility online or suggested doing so would be futile. So they engaged only when comments were civil, but steered clear of arguments.

“If someone is calling me names, I’ll just utterly ignore it,” reported the freelancer with 12 years’ experience. “But if someone makes a good point, I might say, ‘Yeah, that’s a good point.’ If someone says, ‘That isn’t quite right,’ I might say, ‘I was looking at it this way.’ … If someone says I’m an idiot, what can I say? It doesn’t seem worth it.”

A Minority of Journalists Interviewed Say They Never Engage with Commenters

A third of the journalists we interviewed expressed strong feelings that it is inappropriate for them to ever engage with commenters, even in civil discussions. The main reason they stayed away from engaging is they did not see it as part of their jobs. In fact, some saw any form of engagement – even thanking a reader for a positive comment – as a potential breach of their journalistic obligation to be objective. For example, the newspaper reporter with eight years’ experience worried that if she responded to positive comments, her audience might perceive her as biased.

“As a journalist, I think I need to publicly remain impartial not only to what I’m covering but to my coverage,” she said. “I’m hesitant to respond to both positive and negative feedback. I just wonder if that’s an attempt to manipulate my future coverage.”

Many of the journalists saw the comment streams as a place for the public to engage with each other, where journalists did not really belong. “It’s a chance for readers to engage and sound off,” explained a newspaper journalist with 35 years’ experience. “That’s their space.”

Others said they saw it as overstepping their roles as journalists to try to control the conversation or attempt to maintain civility. They preferred to let readers police themselves, by letting them point out each other’s mistakes. Or they felt their efforts to improve the conversation would fail.

“Strict policy at the moment – under absolutely no circumstances will I engage with those who post hate comments,” said a reporter with 4 years’ experience who works at a web-only publication. “They are not interested in debate. I have seen this on other peoples’ website as well. It just escalates.”

Some felt unprepared to tame incivility, noting that they worried they would get into an argument with the commenters or lose their tempers. “I feel like it would be difficult to respond to the comments in a way that it wasn’t me defending myself,” said the reporter with eight years’ experience.

Methodology

Journalist Interviews

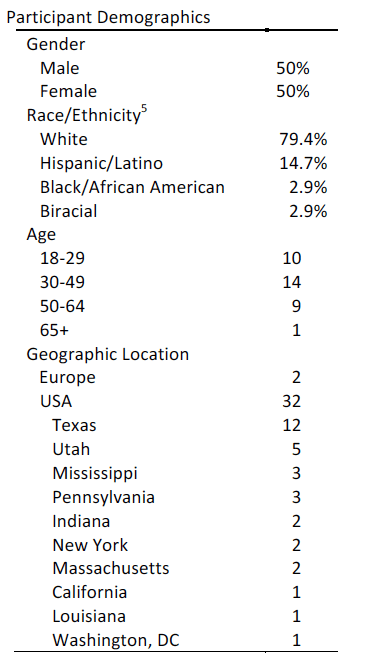

To find journalists to interview, we started by asking journalists we knew. We also sought referrals from our journalism faculty colleagues, as well as from social media and listservs geared to journalism professors and journalists. Whenever a person agreed to be interviewed, we asked that person to suggest other journalists we could interview. Our goal was to have as diverse a sample of journalists to interview as possible. We wanted diversity in terms of gender, age, race, as well as geographic location. We ended up interviewing 34 journalists. This comprises 32 American journalists, one journalist located in Spain and one in the United Kingdom. The table below shows the demographic breakdown of the journalists we interviewed.5

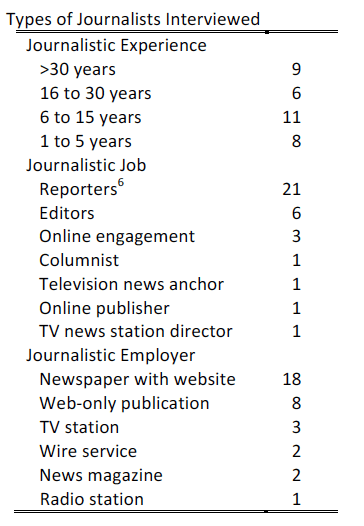

We wanted to interview journalists who worked for a wide range of media organizations, including newspapers, magazines, radio, television, and web-online publications, so we could get a fuller picture of what journalists think about comments. The journalists’ experience on the job ranged from 1 to 40 years, with an average of 17 years. Most worked as reporters, although editors, a television news anchor, and an online publisher were among the ranks. The table below details the experience, jobs, and type of employers of the journalists we interviewed.6

We conducted the interviews by phone from February 5 to March 10, 2016. Interviews lasted 15 to 45 minutes, with an average length of 21 minutes. All were recorded, and sometimes we also took handwritten notes to highlight important portions of the interview. We asked the journalists a series of questions about whether they read comments posted on their news organizations’ website or social media pages, whether they responded to comments, and how they handled uncivil comments. Additional questions were added in the flow of the interview. Mainly, we were interested in letting the journalists tell their stories about how they handle comments.

In all cases, the journalists were prompted to speak broadly about their experiences with commenting, regardless of whether the comments were posted on the news organizations’ website or on its Facebook, Twitter, or other social media pages.

To analyze our interviews, we read through our notes and replayed the recordings, searching for commonalities in what the journalists were saying. We then categorized what they were saying into groups of quotes or paraphrases that answered our initial questions about how they handled comments.

SUGGESTED CITATION:

Chen, Gina Masullo and Pain, Paromita. (2016, August). Journalists and online comments. Center for Media Engagement. https://mediaengagement.org/research/journalists-and-online-comments

- Canter, L. (2013). The misconception in the online comment threads: Content and control on local newspaper websites,” Journalism Practice, 7(5), 604-619; Nielsen, C. (2012). Newspaper journalists support online comments, Newspaper Research Journal, 33(1), 86-100; Mabweazara, H.M., (2014). Reader comments on Zimbabwean newspaper websites,” Digital Journalism, 2(1), 44-61. [↩]

- Nielsen, 2012. [↩]

- Canter, 2013; Mabweazara, 2014. [↩]

- See the Center for Media Engagement report “Journalist Involvement in Comment Sections” at https://mediaengagement.org/research/journalist-involvement/ [↩]

- Numbers do not add up to 100 because of rounding. [↩]

- Some reporters also had editing duties in addition to their reporting duties. [↩]