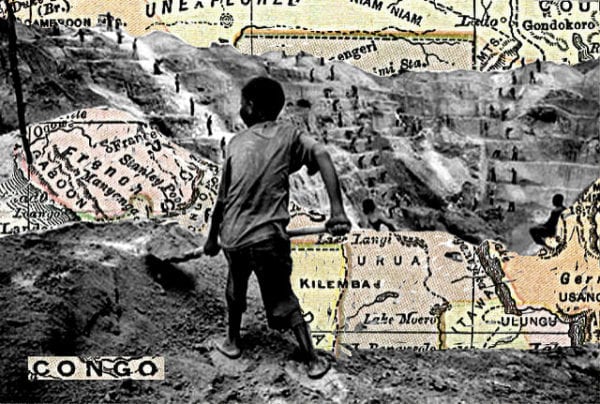

Laura Heaton, a reporter for the NGO, traveled to Luvungi in 2011, a village in the Democratic Republic of the Congo that was known for atrocities such as mass rape that the community had endured in war-torn past decades. These women had all been attacked by rebel troops surrounding the village as a further weapon in the violence. Many articles had been written on the mass rape—the largest instance in the world, with 242 reported survivors over a period of four days—with detailed reports from the women on their experiences and trauma.

A couple of years after all the stories had been published, Heaton traveled back to Luvungi with the goal of speaking to the community about how things have improved (or not) since the last reports had been made about the crimes against this community. When she arrived, she was greeted with villagers simply lining up to once again repeat their stories of their “systematic rape.” After listening to the stories, she sensed that something was wrong. After looking for more information from the doctors of the village and some of the women themselves, Heaton arrived at a startling realization: although over 200 women had reported being survivors of rape, the actual numbers of rape victims seemed much lower.

Most of the women, Heaton learned, didn’t come forward with stories until after the many Non-Governmental Organizations arrived on the scene to help victims of the violence and rape. As Heaton continued in her research and talked to more of the women (promising anonymity) she realized that most of them had lied in an attempt to get much-needed medical help from the NGOs. The organizations gave more food and attention, she claimed, to women who simply said that they had survived rape.

After talking with the women and learning the truth, Heaton wrote and published an article titled “What Happened in Luvungi?” for Foreign Policy about her findings. While she didn’t critique the amount of aid given to Luvungi—“no one suggests that giving millions of dollars to help this vulnerable, traumatized, population isn’t warranted”—Heaton did question the heavy emphasis on sexual violence in aid organizations (Heaton, 2013). She noted that this may have created the perception that women only get adequate support and welfare if they are victims of rape. Caring for this community, she continued to visit the village periodically to stay up to date with the women and their experiences.

Since publishing the article, Heaton has received heated criticism about her story. Eve Ensler, a playwright who opened a recovery center in the Congo in 2011, told Heaton that the article was unnecessary and will lead to new problems for the women of the Congo. Ensler argued that by pointing out the lying of many of the women involved, the people who funded the recovery centers and foreign aid might not see this as a cause worth supporting any more. Because some women lied, now all the women who did need help and who had been victims of rape would be hurt even more. In another follow-up article posted on Foreign Policy, Micah Williams and Will Cragin disputed her facts and accused her of simply wanting to discredit rape victims.

Heaton felt very conflicted about her position. As a reporter, she believed in telling the truth and nothing but the truth. Like many reporting on war-torn areas of Africa, she also felt that the west too often forgot the problems it helped to create on the continent with its policies and legacy of colonialism. Her article ostensibly focused on the problems with inflating rape numbers, and was not arguing that rape isn’t a problem in similar areas of Africa. However, she herself began to question how much the truth matters in journalism if it conflicts the pursuing the general welfare, leading her to recently question if publishing her original article was the right thing to do as a journalist concerned about African communities (Warner, 2017).

Discussion Questions:

- What values are in conflict in Heaton’s account of the Luvungi situation and its reporting?

- What went wrong in the original reporting of the Luvungi atrocities? Did Heaton do the right thing in her reporting on the situation and past stories?

- Should Heaton have looked the other way on “correcting” the previous Luvungi stories? What if her corrections hurt donations and attention to this war-torn area?

- How should a journalist balance the consequences of their reporting for the social good versus the journalist duty to tell the truth? What if telling the truth mitigates the help a story could bring to a community?

- Do reporters have a duty to correct past reporting done by others, especially when it might undo helpful effects of those already published accounts?

Further Information:

Heaton, Laura. “What Happened in Luvungi.” Foreign Policy, 4 March 2013.

Available at: www.foreignpolicy.com/2013/03/04/what-happened-in-luvungi/

Warner, Gregory, and Fountain, Nick. producers. “The Congo We Listen To.”

Rough Translation, Episode 1, National Public Radio, 28 August 2017. Available at:

www.npr.org/templates/transcript/transcript.php?storyId=545879897

Williams, Micah, and Cragin, Will. “Our Experience in Luvungi.” Foreign Policy, 5

March 2013. Available at: www.foreignpolicy.com/2013/03/05/our-experience-in-luvungi/

Authors:

Emma Matus & Scott R. Stroud, Ph.D.

Media Ethics Initiative

Center for Media Engagement

University of Texas at Austin

February 12, 2019

Image: Natasha Mayer / CC BY-SA 2.0

This case study can be used in unmodified PDF form for classroom or educational settings. For use in publications such as textbooks, readers, and other works, please contact the Center for Media Engagement.

Ethics Case Study © 2019 by Center for Media Engagement is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0