It’s no secret that pollution has a drastic impact on the earth. Each year, plastic is one of the most common pollutants found in our oceans and landfills. In fact, it is estimated by 2050 there will be more plastic than fish in our oceans (Kaplan, 2016). Much of this pollution can be traced back to large corporations and their impact on the environment. Because such companies often have enormous amounts of funding, many believe they should put it towards cleaning up their environmental messes and carbon footprints. However, this pressure from the public has led to the issue of Greenwashing – when a brand claims to be better for the environment than it really is (Edwards, 2022).

There are many brands that try hard to protect the environment. For example, Patagonia’s founder Yvon Chouinard announced that he wants to give the outdoor clothing retailer “to the world” (Patagonia, “Patagonia’s Next Chapter”). His wife and children gave their shares of the company (totaling over three billion dollars) to non-profit organizations in an effort to use business profits to give back to the earth. Moreover, Patagonia hopes to encourage their customers to think about the role consumerism plays in climate change. In 2011, the company ran a now-iconic full-page ad in The New York Times that said “Don’t Buy This Jacket” to encourage responsible, thoughtful shopping during the busiest retail day of the year (Patagonia, “Don’t Buy This Jacket, Black Friday and the New York Times”). Since then, the company has continued to run unique and thought-provoking ads around Black Friday, such as the more recent “reversible poem” ad that, at first glance, appears to be a fatalistic account of climate change, but switches to a message of hope when read backwards (Beer, 2020).

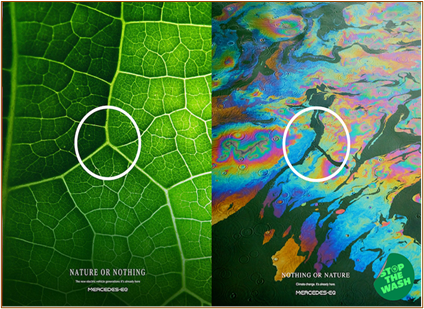

Despite the work of brands that are truly trying their best, there are also plenty that get called out for not doing enough. For example, Windex’s 2020 “Help Seas Sparkle” campaign claimed their product “Windex Vinegar Glass Cleaner” would be the “first-ever” plastic bottle created from 100 percent recycled “ocean plastic” (Windex, 2020). Many customers believed this meant Windex was removing plastic from the ocean to create bottles, but that was not the case. Instead, this “ocean plastic” was being retrieved not from the ocean, but from plastic banks in Haiti, the Philippines, and Indonesia (Toto, 2019). While the plastic was recycled and some had been found anywhere up to thirty miles from an ocean or waterways to prevent the further pollution of water, the ad was slammed for using the term “ocean plastic” in a misleading way that left consumers confused (Moxie Future, 2020). Similarly, Mercedes-Benz recently came under fire for their “Nature or Nothing” campaign promoting a new line of electric automobiles. The ads show the Mercedes logo enmeshed within different visuals from nature, such as the veins of a leaf and honeycombs (Truth in Advertising, 2022). However, many were upset by this move since the luxury car company has been “sued several times in recent years for cheating on emissions tests” (Truth in Advertising, 2022). In response, a sustainability group hijacked the ad, depicting the Mercedes logo over visuals of environmental damage, such as oil spills and Arctic ice cracks, since those images align more closely with Mercedes’ actual environmental footprint (Truth in Advertising, 2022). Indeed, making an electric car does little to give back to the environment, especially at its hefty six-figure price point.

Pollution increases every year, and with that comes difficulty in deciding how to move forward. Corporations should care about their environmental footprint, but some rely on greenwashing rather than genuine solutions for addressing the climate crisis, which can also make it difficult for the public to trust the companies that are seemingly keeping their promises to work towards greener business practices. That said, it is easy to point fingers at large corporations and claim they are not doing enough – but what actually is “enough”? Despite generally positive responses to their actions, even Patagonia has faced criticism from some (Wood, 2022). We can all agree it’s not ideal for a company to ignore its environmental impact, but how much does a company have to do to avoid being accused of greenwashing?

Discussion Questions:

- How would you define greenwashing in advertising? What is ethically problematic about this practice?

- What ethical values are in conflict companies try to “greenwash” their image or products? Why might it be reasonable for companies to use these sorts of appeals in their ads?

- Can you outline a few ethical principles that could guide companies in ethically using environmental appeals in their advertising?

- How could a company design a campaign for one of the products mentioned in this case (or a product supplied by your instructor) that emphasizes care for the environment but that avoids greenwashing?

Further Information:

Beer, Jeff. (2020, November 30). “Patagonia’s reversible poem ad is a check on runaway Black Friday Cyber Monday spending.” Fast Company. Available at: https://www.fastcompany.com/90580854/patagonias-palindrome-poem-ad-is-a-check-on-runaway-black-friday-cyber-monday-spending

Edwards, Carlyann. (2022, August 5). “What is Greenwashing?” Business News Daily. Available at: https://www.businessnewsdaily.com/10946-greenwashing.html

Kaplan, Sarah. (2016, January 20). “By 2050, there will be more plastic than fish in the world’s oceans, study says.” The Washington Post. Available at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/morning-mix/wp/2016/01/20/by-2050-there-will-be-more-plastic-than-fish-in-the-worlds-oceans-study-says/

Moxie Future. (2020, December 18). “8 brands called out for greenwashing in 2020,” Available at: https://moxiefuture.com/2020/12/8-brands-called-out-for-greenwashing-in-2020/

Patagonia. (2022, September 14) “Patagonia’s Next Chapter.” Available at: https://www.patagoniaworks.com/press/2022/9/14/patagonias-next-chapter-earth-is-now-our-only-shareholder

Patagonia. (n.d.). “Don’t Buy This Jacket, Black Friday and the New York Times.” Available at: https://www.patagonia.com/stories/dont-buy-this-jacket-black-friday-and-the-new-york-times/story-18615.html

Toto, DeAnne. (2019, February 27). “SC Johnson launches Windex bottle made completely from ocean plastics.” Available at: https://www.recyclingtoday.com/article/sc-johnson-launches-windex-bottle-made-with-ocean-bound-plastics/.

Truth in Advertising. (2022, September 1). “Mercedes Accused of Greenwashing.” Available at: https://truthinadvertising.org/articles/mercedes-accused-of-greenwashing-with-nature-or-nothing-ads/

Windex. (2020). “Help Seas Sparkle.” Available at: https://www.windex.com/en-us/help-seas-sparkle

Wood, Robert Jackson. (2022, October 5). “Patagonia’s Greenwashing Ignores Workers and Won’t Solve the Climate Crisis.” Truthout. Available at: https://truthout.org/articles/patagonias-greenwashing-ignores-workers-and-wont-solve-the-climate-crisis/

Authors:

Kayla Madureira, Kat Williams, & Scott R. Stroud, Ph.D.

Media Ethics Initiative

Center for Media Engagement

University of Texas at Austin

January 12, 2023

Image from Truth in Advertising

This case was supported by funding from the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. It can be used in unmodified PDF form in classroom or educational settings. For use in publications such as textbooks, readers, and other works, please contact the Center for Media Engagement.

Ethics Case Study © 2023 by Center for Media Engagement is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0