People with disabilities are one of the largest minority groups in the world (World Health Organization, 2021). Yet in fashion, they have been historically underrepresented (Haines, 2021). This is slowly changing, however, and adaptive fashion –defined as clothing, accessories or footwear specially designed around the needs of people with varying disabilities– is now on the rise (Amputee Coalition, 2019). From magnetic closures to sensory-friendly fabrics and wheelchair-specific outfits, adaptive fashion offers practical and stylish clothes for people with disabilities. This inclusive fashion revolution can be even seen in the marketing of high-profile brands like Victoria’s Secret and their new line of diverse Angels (D’Zurilla, 2021), Tommy Hilfiger’s “Tommy Adaptive” fashion line created in 2016 (Webb, 2021), and Nike’s Go FlyEase shoe that wearers step in and out of “hands free” (Weaver, 2021). Indeed, by 2026, the industry is expected to be valued at $400 billion (Gaffney, 2019).

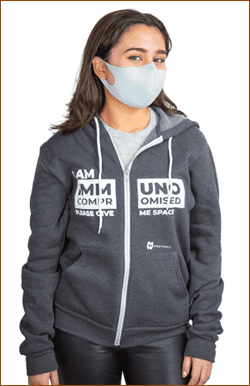

Despite the high need for adaptive fashion and the newly exploding industry, the artificial intelligence (AI) used to filter social media advertisements is not innovating at the same pace. For example, in early 2021, the adaptive fashionwear company Mighty Well tried placing an ad on Facebook for a gray hooded sweatshirt with the text “I am immunocompromised – please give me space.” Immediately, Facebook’s AI system that accepts or rejects advertisement requests, denied Mighty Well’s ad (Friedman, 2021). Facebook reasoned that the ad violated their policy of advertising “medical and healthcare products and services including medical devices” (Friedman, 2021). Similarly, the inclusive clothing company Yarrow also ran into issues with Facebook advertising. When their ad for a pair of pants featured a model who uses a wheelchair was submitted, Facebook’s AI again denied the ad – this time, due to the image of the wheelchair, not the actual product. In both cases, Facebook’s AI system missed the mark on what these companies were actually attempting to advertise. Thankfully, after both Mighty Well and Yarrow resubmitted their ad requests, Facebook eventually accepted both and apologized for their AI’s oversights (Friedman, 2021).

Although both companies were, ultimately, able to advertise their products, many have questioned why it took so much time and effort for the ads to make it onto Facebook’s platform. For some, the answer is simple: biased gatekeeping delayed inclusive advertising for adaptive fashion. While some may argue that this problem is due to technological error rather than intentional discrimination by humans, critics point out that Facebook’s advertising AI is coded by humans. Kate Crawford, author of the forthcoming book Atlas of AI, explains that AI excels at “large-scale classification” and “is very bad at detecting nuance” (Friedman, 2021). Nuance –in this sense, attention to clothing details that could make getting dressed easier for people disabilities— is what adaptive fashion is all about. If “regular,” fashion brands for abled bodies don’t have to run into issues like this when marketing their products, inclusive and adaptive fashion companies should not have to either.

However, fixing the problem is easier said than done. While imperfect, Facebook’s advertising AI is valuable. Indeed, it would be dangerous if there were no barriers at all to advertising on the platform, as anyone could place ads for, say, random pills or faulty medical equipment. And while it could be argued that this job should be given to humans instead, Facebook’s content moderators are already overburdened with reviewing hundreds of posts per day – many of which cause workers to develop PTSD from continued exposure to graphic content (Criddle, 2021). In this sense, the AI performs the incredibly important job of decreasing the information overload that makes it to Facebook’s human moderators, and in doing so, rejects suspicious ads that vulnerable people may be suspectable to. The question then, is how the AI can be trained to draw the line between shady medical products and legitimate products like adaptive clothing.

Unfortunately, Mighty Well, Yarrow, and other inclusive fashion companies may start to stray away from using Facebook advertising if problems with the AI aren’t addressed in a swift manner. For example, Abilitee Adaptive, which made accessories for insulin pumps and ostomy bags until 2020, already stopped advertising on Facebook and Instagram due to frequent and frustrating rejections (Friedman, 2021). And since Facebook “currently sits at more than 2.89 billion monthly active users,” adaptive fashion companies feeling forced to abandon these platforms altogether may mean that fewer people with disabilities – who could really benefit from clothing made specifically for them— will even be aware of some of the new options now on the market (Statistica, 2022). Furthermore, if the problem of able-biased AI isn’t addressed on one social media platform (let alone the largest and most popular), other platforms may resist updating their algorithms too.

In the end, whether or not Facebook will devote the time and resources necessary to promptly fix their AI’s bias has yet to be seen. But while the company is dragging its feet to do so, these problems will only increase as the adaptive fashion industry continues to evolve and grow. To ensure that everyone can finally feel seen and heard in fashion, it is crucial for social media platforms to make taken-for-granted privileges –like the ability to easily market clothes for abled-bodies—accessible to all.

Discussion Questions:

- What ethical values are in conflict in this case about Facebook’s advertising AI?

- How would you suggest that Facebook address their AI’s problems with distinguishing between fake and honest product submissions?

- While AI improvements are developed and tested, how would you suggest that adaptive fashion companies like Mighty Well and Yarrow navigate the issues they will continue to face with advertising on Facebook and other social media platforms?

- What are the limitations to using AI to police advertisements? What are the concerns with using humans to do the same task?

Further Information:

Amputee Coalition. (2019, May). Adaptive Clothing Resources. Available at: https://www.amputee-coalition.org/resources/adaptive-clothing-resources/

Criddle, C. (2021, May 12). “Facebook Moderator: ‘Every Day Was a Nightmare.’” BBC News. Available at: https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-57088382

D’Zurilla, C. (2021, June 17). “Victoria’s Secret Retires its Angels, Deciding They’re Not Culturally Relevant.” Los Angeles Times. https://www.latimes.com/entertainment-arts/story/2021-06-17/victorias-secret-rebrand-influencers-angels

Friedman, V. (2021, February 11). “Why is Facebook Rejecting These Fashion Ads?” New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/02/11/style/disabled-fashion-facebook-discrimination.html

Gaffney, A. (2019, July 29). “The $400 Billion Adaptive Clothing Opportunity.” Vogue Business. https://www.voguebusiness.com/consumers/adaptive-clothing-differently-abled-asos-target-tommy-hilfiger

Haines, A. (2021, June 24). “The Fight for Adaptive Fashion: How People with Disabilities Struggle to be Seen.” Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/annahaines/2021/06/24/the-fight-for-adaptive-fashion-how-people-with-disabilities-struggle-to-be-seen/?sh=1b975a15694d

Statistica. (2022, January). “Most Popular Social Networks Worldwide as of January 2022, Ranked by Number of Monthly Active Users.” Available at: https://www.statista.com/statistics/272014/global-social-networks-ranked-by-number-of-users/

Weaver, J. (2021, May 14). “How the Nike Go Flyease Upended the World of Adaptive Fashion.” CBC News. https://www.cbc.ca/news/entertainment/flyease-adaptive-fashion-1.6026277

Webb, B. (2021, March 22). “Tommy Hilfiger Ramps Up Adaptive Fashion. Who’s Next?” Vogue Business. https://www.voguebusiness.com/fashion/tommy-hilfiger-ramps-up-adaptive-fashion-whos-next

World Health Organization. (2021, November 24). Disability and Health: Key Facts. Available at: https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/disability-and-health

Authors:

Meghan Barrasso, Kat Williams, & Lisa Perks, Ph.D.

Merrimack College / University of Texas at Austin

Center for Media Engagement

August 25, 2022

Image: Screenshot from Mighty Well

This case was supported by funding from the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. It can be used in unmodified PDF form in classroom or educational settings. For use in publications such as textbooks, readers, and other works, please contact the Center for Media Engagement.

Ethics Case Study © 2022 by Center for Media Engagement is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0