On October 31, 1984, two of Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi’s bodyguards assassinated her. The political killing came four months after the Prime Minister ordered the raid and siege of a shrine in the Punjabi city of Amritsar’s Golden Temple complex. Sikh separatists controlled the temple and Gandhi sent the Indian Army to oust them from the holy site. Hundreds died; an Indian Army general called it a “killing ground” (Raj & Najar, 2014). The two bodyguards and a third co-conspirator were Sikhs who sought revenge by killing the Prime Minister. Following their ambush of Gandhi, one was shot dead by police in the immediate aftermath of the assassination, and the second was hanged in 1989 for the crime alongside the third. The assassination provoked nationwide violence, with the communal retaliation resulting in the deaths of over 3,000 Sikhs.

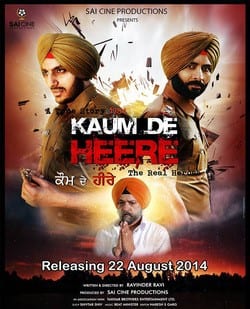

Thirty years later, a film titled “Kaum De Heere”—which translates to “Diamonds of the Community”—was on the verge of opening in India. It would not be the first film to deal with Prime Minister Gandhi’s life, legacy, or death, but it would be the first to center on her assassins. In 2014, days before it was slated to be released the Central Board of Film Certification (CBFC) reversed its clearance of the movie and blocked it from distribution after Home Ministry objections that it could create religious tensions. Leela Samson, the CBFC chairperson, said “the problem lies in the fact that [the film] eulogizes things it shouldn’t … like taking the law into your own hands” (Raj & Najar, 2014). Religious tensions were particularly high when discussing the film, furthering Samson’s concern that it “puts a community or religious group above the interests of the nation” (Raj & Najar, 2014). Citing similar tensions, intelligence agencies warned the film could spark violence among religious communities within India. Youth in the Indian National Congress Party lobbied the current Indian prime minister, Narendra Modi, to ban the film because it allegedly glorified the assassins.

One of the producers, Pardeep Bansal, countered these criticisms, stating that “it is a completely balanced film wherein no religion or sect has been belittled” (Raj & Najar, 2014). Another producer, Ravinder Ravi, claimed to have spent time with the families of the two assassins—Satwant and Beant Singh. He argued, “films have been made about political assassinations all over the world, so why can’t a film be made” about Prime Minister Gandhi’s (Biswas, 2014)? What’s more, the Revising Committee screened the film multiple times before originally granting clearance adding to speculation that the Congress Party and Bharatiya Janata Party called for the reversal. By October 2014, the producers had filed an appeal of the decision.

Fast forward to 2019 and the film is finally slated for release. Justice Vibhu Bakhru of the Delhi High Court, which overturned the CBFC ban, argued once the body clears a film, they cannot use law and order as an excuse to halt its release. Bakhru also stated that the board improperly used the unconstitutional Section 6(1) of the Cinematograph Act to justify their decision. The now illegitimate section “enable[d] the Central Government to exercise revisional powers in respect to decisions rendered by CBFC,” and in this case, the procedure dictated by the now defunct policy was not even followed properly, per the high court (Press Trust of India, 2019). The court’s finding supports the producers’ appeal, which argued there was “no factual or legal basis for withdrawal of certificate” to release the film (Press Trust of India, 2019), dismissing concerns of renewed violence as either immaterial or improbable. None of the speculated violence behind the CBFC decision has come to pass since the court cleared the film for release at the end of August and the Congress Party and Bharatiya Janata Party have not mounted significant protests, yet religious tensions are still simmering.

Meanwhile, a new web series on Prime Minister Gandhi is under production. Actress Vidya Balan, who will play Gandhi, claims the series “is not about any political party, [it] is about an individual who goes beyond the party” (Indo-Asian News Service, 2019). Perhaps it too will run into trouble clearing the CBFC; after all, Balan’s argument could just as easily be applied to the Sikh bodyguards as the Prime Minister she’s slated to portray. How can the values of free speech, artistic freedom, and communal safety be balanced in the turbulent media environment of India?

Discussion Questions:

- What issues are at stake in dramatized retellings of contentious history, such as the events of Gandhi’s administration or her assassination?

- What consideration, if any, should the CBFC—or similar bodies elsewhere—give to political and cultural climate when making censorship decisions?

- When making a movie about historical events, is there an ethical responsibility to condemn—or at least not to encourage or valorize—violence and its perpetrators?

- More broadly, how do ethics relate to artistic products? Are there subjects that are simply not suitable for art?

Further Information:

Soutik Biswas, “Indira Gandhi assassination: Controversial film blocked.” BBC News, August 22, 2014. Available at: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-28892001

Indo-Asian News Service, “Vidya Balan on why she decided to make web series on Indira Gandhi.” India Today, August 28, 2019. Available at: https://www.indiatoday.in/television/web-series/story/vidya-balan-on-why-she-decided-to-make-web-series-on-indira-gandhi-1592657-2019-08-28

Press Trust of India, “Delhi HC clears release of Punjabi movie ‘Kaum De Heere.’” Business Standard, August 29, 2019. Available at: https://www.business-standard.com/article/pti-stories/delhi-hc-clears-release-of-punjabi-movie-kaum-de-heere-119082900771_1.html

Suhasini Raj and Nida Najar, “Film about Indira Gandhi’s assassination is barred from Indian Theaters.” The New York Times, August 22, 2014. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2014/08/23/world/asia/film-about-indira-gandhis-assassination-is-barred-from-indian-theaters.html

Authors:

Dakota Park-Ozee & Scott R. Stroud Ph.D.

Media Ethics Initiative

Center for Media Engagement

University of Texas at Austin

January 22, 2020

Image: Theatrical Release Poster

This case was produced by the Center for Media Engagement with support from the South Asia Institute. It can be used in unmodified PDF form for classroom or educational settings. For use in publications such as textbooks, readers, and other works, please contact the Center for Media Engagement.

Ethics Case Study © 2020 by Center for Media Engagement is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0