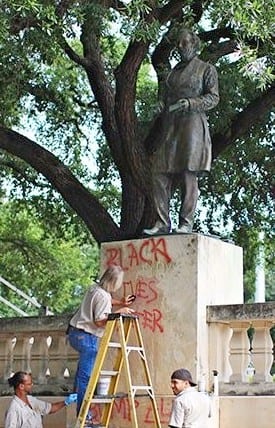

In the dead of night of August 20, 2018, the University of Texas removed four statues on the south mall of the campus. Three of these statues depicted the Confederate leaders: Robert E. Lee, Albert Sidney Johnston, and John Reagan. The statues were removed in response to violent protests over Confederate monuments in Charlotte, Virginia. Two years before these statues were removed, the university took down a prominent statue of Jefferson Davis, the Confederate president. The University of Texas president, Gregory Fenves, stated that these statues were removed because they are depictions “that run counter to the university’s core values.” The men portrayed by the statues were important figures in the history of the Civil War and the United States, but many argue that they stood for a cause that is contrary to the values of our current society. Much debate has risen as to whether figures like these should be presented and honored in our public areas.

Some argue that these statues must remain to remind us of our nation’s history, whether that history is good or bad. They claim that these monuments do not have to represent a celebration of slavery or a commemoration to the Confederacy, but rather as a reminder of our past. For instance, Lawrence Kuznar of the Washington Post argues that “when racists revere these monuments, those of us who oppose racism should double our efforts to use these monuments as tools for education. Auschwitz and Dachau stand as mute testimonials to a past that Europeans would never want to forget or repeat. Why not our Confederate monuments?” In an attempt to shift the focus of these monuments to education, many local governments have chosen to supplement confederate monuments with additional context and information to increase its educational value. For example, a historical commission in Raleigh, North Carolina voted to supplement its confederate statues “with adjacent signs about ‘the consequences of slavery’ and the ‘subsequent oppressive subjugation of African American people.’” Supplemental information is provided to help to relieve the negative effect of the statues while maintaining or increasing their educational value.

To many other observers, however, these statues can only be perceived as a symbolic celebration of white power and racial inequality because of the people they depict. To some, the symbolic significance of the statues outweighs any historical significance. Ilya Somin, a professor at George Mason University, believes that “no one claims that we should erase the Confederacy and its leaders from the historical record. Far from it. We should certainly remember them and continue to study their history. We just should not honor them.” The men commemorated by the statues in discussion fought to defend slavery. Although the institution of slavery has been removed from the United States, racial divides still dominate much of the social and political discourse. For opponents of these statues on Texas’s campus, honoring these white men who risked their lives and the unity of their country to protect their right to enslave others does not present a positive image for furthering the contemporary cause of racial equality. The historical lesson depicted by these statues could, some argue, be preserved in a museum without the implications of placing a negative symbol in a public area.

Proponents of the removal of confederate statues often challenge the primary motivations for building these statues. Typically, the statues in question were not created during the Civil War or even during the reconstruction era. The four confederate statues at UT were placed in 1933, nearly 70 years after the end of the Civil War. Some argue that the decision to commemorate the Confederate leaders may reveal more about the statues’ builders’ desires to maintain segregation in the 1930s than the commemorated men’s fight to protect slavery in the late 1800s. The University of Texas president, Gregory Fenves, defended the University’s decision to remove the statues by referencing the historical context of when the statues were built. He argued that because the statues were “erected during the period of Jim Crow laws and segregation” this implied that “the statues represent the subjugation of African Americans.” The statues were commissioned by George Littlefield, a man who supported segregation so strongly that “the inscription on his namesake fountain honors the South’s fight for secession.” Supporters of the removal of the statues contend that the statues do not create a welcoming educational environment for African American students, past or present.

Statues of notable figures as those that dot campuses such as the University of Texas at Austin provide a powerful way to integrate the history of regions and institutions into everyday spaces. But they also enshrine histories that are value-laden, and our moral values change over time. Who should be honored in our monuments, and when should we knock certain figures off their literal pedestals in our public spaces?

Discussion Questions:

- What are the various values in conflict when it comes to monuments honoring confederate leaders?

- What role to the motives or intentions of those who installed the statue play in the ethics of removing or leaving in place such statues? What role do our contemporary reactions to the memorialized figures play these disputes?

- To what lengths can communities go in their quest to remove these statues? Is vandalism and destruction of these statues ethically problematic? Why or why not?

- Is there any hope for these statues being “reframed” in public spaces? Or is removal the only option?

- Are there any ethical issues or considerations that must be dealt with if the removed statues are displayed elsewhere, such as in a museum?

Further Information:

Nelson, Sophia. “Opinion: Don’t Take Down Confederate Monuments. Here’s Why.” NBC News, June 1, 2017. Available at: https://www.nbcnews.com/think/news/opinion-why-i-feel- confederate-monuments-should-stay-ncna767221

Kuznar, Lawrence. “I detest our Confederate monuments. But they should remain.” The Washington Post, August 18, 2017. Available at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/i-detest-our-confederate-monuments-but-they-should-remain/2017/08/18/13d25fe8-843c-11e7-902a-2a9f2d808496_story.html

Watkins, Matthew. “UT-Austin removes Confederate statues in the middle of the night.” Texas Tribune, August 21, 2017. Available at: https://www.texastribune.org/2017/08/20/ut-austin-removing-confederate-statues-middle-night/

Somin, Ilya. “The case for taking down Confederate monuments.” The Washington Post, May 17, 2017. Available at https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/volokh-conspiracy/wp/2017/05/17/the-case-for-taking-down-confederate-monuments/

Waggoner, Martha & Robertson, Gary. “North Carolina will keep 3 Confederate monuments at Capitol.” Associated Press, August 22, 2018. Available at https://apnews.com/c0cb1c1ed22a4302bb638748a4e62217

Fenves, Gregory (2017). Confederate Statues on Campus [transcript]. Retrieved from https://president.utexas.edu/messages/confederate-statues-on-campus

McCann, Mac. “Written in Stone: History of racism lives on in UT monuments” Austin Chronicle, May 29, 2015. Available at https://www.austinchronicle.com/news/2015-05-29/written-in-stone/

Authors:

Colin Frick & Scott R. Stroud, Ph.D.

Media Ethics Initiative

Center for Media Engagement

University of Texas at Austin

October 31, 2018

Top Image: Jesus Nazario

This case study can be used in unmodified PDF form for classroom or educational settings. For use in publications such as textbooks, readers, and other works, please contact the Center for Media Engagement.

Ethics Case Study © 2018 by Center for Media Engagement is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0