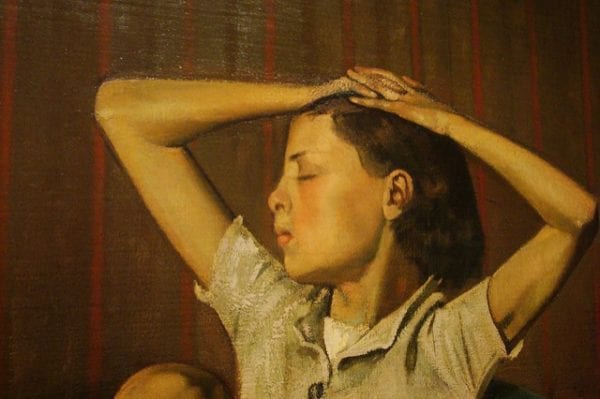

A painting at the Metropolitan Museum of Art titled Thérèse Dreaming (1938), painted by the French artist Balthasar Klossowski de Rola (or simply, Balthus), depicts a young girl in a suggestive pose, “leaning back in a wicker chair, eyes closed, arms clasped above her head, her knees are splayed open and her red skirt is flipped up to reveal a pair of white underwear.” The girl in this painting was said to be Balthus’ neighbor who modeled for him for several years, who was around 12 or 13 years of age at the time.

Mia Merrill visited the museum and was shocked and disturbed by this piece in particular. Leveraging the growing societal concerns with sexual harassment, Merrill created an online petition to have the museum remove the piece. She later altered her demands, suggesting the alternative of the Met editing the description accompanying the painting to better inform people about the “potentially disturbing nature” of the piece. Merrill’s concern about the painting was fueled by today’s climate around sexual assault and the #MeToo movement. Her worry is that museums aren’t doing their part in standing up for women and minors when they are being objectified or sexualized in paintings that are hanging on their walls. Merrill was not alone in her objections to showcasing this work: her petition received over 11,000 signatures.

Priscilla Franks notes that Merrill’s petition simply crystalized an ongoing worry in the #MeToo era: “Some have wondered, in particular, whether museums have a responsibility to change the way they present work that sexualizes or objectifies women ― especially vulnerable populations like minors and sex workers. What should become of images made under murky conditions, when a female subject’s dignity, agency and safety were potentially at risk?” As Merrill stated in an interview, “at the end of the day, we’re talking about an artist who asked very young girls to come to his studio and take their clothes off. What does that do to the question of consent?” This is important, Merrill notes, since “the Met is, perhaps unintentionally, supporting voyeurism and the objectification of children.” If museums enshrine and valorize “great art,” should works created under such conditions be rewarded with this spotlight?

Shortly after Merrill’s petition, the Met announced that they would not be making any changes to Thérèse Dreaming. They added that “moments such as this provide an opportunity for conversation” and that “visual art is one of the most significant means we have for reflecting on both the past and the present.” The National Coalition Against Censorship also agreed with the museum’s decision to not remove the painting or alter the text accompanying it.

Some art critics voiced their opposition to Merrill’s demands, saying that if this painting were to be taken down because of its content and production history, then there would be many others that would also have to be removed, including works from artists such as Picasso, Klimt, and Munch. During this era, women were usually the subject of these paintings and often were depicted nude. These artists were also, for the most part, male, and therefore implicated in Merrill’s concern with western art’s “dominant male narrative.” How much art is to be thrown out or reframed if we take into account often-problematic cultural contexts of their production history?

However, most of these critics also believe that these paintings can be used as a way of teaching about consent and sexualization of women. Ronna Tulgan Ostheimer, the director of education at the Clark Museum argued that discussing the paintings’ problematic context is a “much more valuable choice than putting something out of someone’s eyes.” In the end, a painting’s context of production and history of the artist is crucial to understanding the piece, but the question still remains: how much should museums do to correct the sins of our artistic past?

Discussion Questions:

- What should the Met do about Balthus’ painting? If they leave it on display, should they do anything further to contextualize its history and content? If so, what in particular should they say?

- Do you see any potential conflicts or problems emerging if descriptions of artists or artworks begin to address matters as complex as the consent involved in their production?

- Is the value of a “great” artwork harmed by an immoral context of production? Why or why not? Is this damage to an artwork’s aesthetic value irreparable, or can it be recovered or repaired in some way?

- If an artist—or an artist’s other works—have been found to be misogynistic or racist, does this impugn or harm the value of their other works that aren’t problematic? Could an artist be so toxic that there would exist a reason to never display anything that he or she created in a museum?

Further Information:

Mia Merrill, “Metropolitan Museum of Art: Remove Balthus’ Suggestive Painting of a Pubescent Girl, Thérèse Dreaming.” The Petition Site, November 30, 2017. Available at: https://www.thepetitionsite.com/157/407/182/

Eileen Kinsella, “The Met Says ‘Suggestive’ Balthus Painting Will Stay After Petition for Its Removal Is Signed by Thousands.” Art Net News, December 5, 2017. Available at: https://news.artnet.com/art-world/met-museum-responds-to-petition-calling-for-removal-of-balthus-painting-1169105.

Associated Press, “New York art museum refuses to remove painting of girl after ‘voyeurism’ complaint.” The Guardian, December 5, 2017. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2017/dec/06/new-york-metropolitan-museum-art-refuses-remove-girl-balthasar-klossowski-voyeurism-complaint.

Priscilla Frank, “In The #MeToo Era, Do These Paintings Still Belong In A Museum?” Huffington Post, December 14, 2017. Available at: https://www.huffingtonpost.com/ entry/museums-me-too-sexual-harassment-art_us_5a2ae382e4b0a290f0507176.

Authors:

Bailey Sebastian & Scott R. Stroud, Ph.D.

Media Ethics Initiative

Center for Media Engagement

University of Texas at Austin

July 16, 2018

Image:Regan Vercruysse / CC BY 2.0 / Modified

This case study can be used in unmodified PDF form for classroom or educational settings. For use in publications such as textbooks, readers, and other works, please contact the Center for Media Engagement.

Ethics Case Study © 2018 by Center for Media Engagement is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0