SUMMARY

The threat of online harassment is ever-present for women journalists. Since engaging with audiences over social media is often an expected part of the job, the Center for Media Engagement wanted to find out what kind of harassment female journalists face online, how it affects the way they do their jobs, and how they handle the problem.

Interviews with journalists in Germany, India, Taiwan, the United Kingdom, and the United States suggest that online harassment of women journalists is a global problem that needs to be addressed. Though journalists are expected to engage online, most of the women interviewed faced harassment as a result and felt they had little support from news organizations. Some took steps to protect themselves and others even changed they way they approached reporting as a way to mitigate the problem.

The findings suggest that newsrooms need to invest resources in supporting women as they face harassment on the job and to provide training for how to handle issues as they arise.

PROBLEM

Women journalists face the threat of online harassment as they do their job and try to engage with their audience over social media.1 This harassment — vitriolic sexist attacks or inappropriately sexual barbs — mirrors the experiences many women face online.2 It can be different from the harassment male journalists encounter because it often targets women based on their gender or sexuality. The Center for Media Engagement sought to understand how professional journalists at print, broadcast, and online publications deal with this harassment and what effect it has on their ability to do their jobs, which increasingly require engagement with the public.3

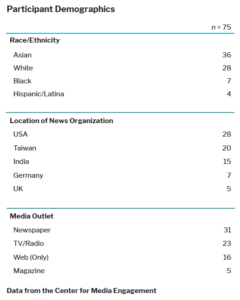

To do this, we interviewed 75 female professional journalists who work or who have worked for news organizations in Germany, India, Taiwan, the United Kingdom, and the United States. We interviewed women from various cultures to more fully understand how harassment influences how women journalists do their jobs. Our interviews included journalists who were new to the profession, as well as those who had spent many years on the job. We analyzed these interviews to look for common experiences, as well as differences, across our sample. The journalists are not identified by name or news organization to encourage candor.

KEY FINDINGS

- Most of the female journalists we interviewed had experienced negative audience feedback that went beyond mere critiques of their work and, instead, often took the form of harassment, targeting them personally with a focus on their gender or sexuality.

- Journalists in India, the U.K., and the U.S. felt strong pressure to engage online as part of their job and often felt they had no choice but to face the harassment.

- Most of the women interviewed felt that they had little support from management and little training on how to handle the abuse.

- The German-speaking journalists in our sample reported less pressure to engage, while the journalists in Taiwan often did not see interacting with their audience as an important part of their jobs.

- Some journalists developed specific strategies for preventing harassment, including limiting what words could be used in comments on their Facebook pages or being more careful to include a variety of voices in a story to head off abuse.

- Some women reported that they felt tension over harassment and opted to ignore the abuse or refrain from engaging on social media as a result.

IMPLICATIONS

Our interviews suggest that online harassment is a prevalent problem across countries and that news organizations need to do more to help journalists — particularly female journalists — as they encounter online harassment. Most of the journalists we interviewed felt pressure to engage online as part of their job, although there was less pressure for journalists in news organizations in Germany and Taiwan. As journalists tried to engage, however, they felt emotionally spent or even physically threatened.

Most of the women we interviewed felt that their news organizations could do more to train them on how to handle abuse and to back them up when harassment happens. Many of the journalists wished their supervisors saw it as part of their job to ensure a safer place to engage, free from online harassment. The women sometimes felt a lack of freedom to report abuse or felt that their news organization saw it as their personal problem. More stringent moderation of online comments and more oversight of professional social media pages were identified as possible solutions.

Overall, the results of the interviews point to a need for more support from news organizations as well as a need for training on how to handle online harassment as part of journalism schools and professional development courses.

FULL FINDINGS

Online Harassment Can Become a Normal Part of the Job

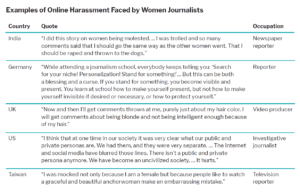

Almost all of the journalists we interviewed reported experiencing some form of harassment online that focused on their person, gender, or sexuality. “It was not criticism of my work; it was actually the destruction of my person,” recalled an online editor who worked for a German news organization.

Some interviewees noted that the abuse differed from what their male colleagues encountered because criticism of their work included sexist attacks or, sometimes, threats of sexual violence. Echoing what other participants shared, an online editor in India reported: “Sex is used to intimidate us. Rape is used to frighten, intimidate, and stop us… from doing our work, but at a deeper level it is actually about stopping us from having opinions, showing any semblance of independence.”

Among the journalists we interviewed, harassment happened most frequently to the 23 television journalists.

Some of the abuse was more benign but still difficult to handle. “Women have to deal with the sexual comments that males never have to deal with,” explained an American online journalist. “You’re viewed more often as a sexual objects … I’ve been told I need to get laid… They’re rare, but they’re so much worse than what my male colleagues have to deal with.”

Journalists said the attacks were most virulent when they covered stories on topics normally associated with men, such as automobiles or video gaming. Divisive topics, such as immigration, race, feminism, or politics, also seemed to elicit greater abuse. For example, a U.S. journalist said she faced denigration when she covered a story on the Black Lives Matter movement, which highlights abuse of African Americans at the hands of police. “The F word was hurled at me in a way that I have never experienced before. It was a frenzy,” she said.

Similarly, a British video producer encountered intense harassment, filled with references to her gender, when she produced a story about Halal certification, a process that ensures food has been prepared according to Islamic law. She recalled: “They made some really horrible, racist comments that I should go join ISIS. I even received comments about the color of my hair being blonde, so how can I be intelligent in any sort of way?”

Some broadcast journalists we interviewed reported that audience members either told them they were too fat or ugly to be on television or peppered them with unwanted sexual invitations that undermined their value as professionals. An anchorwoman in Taiwan explained: “Most of my followers on Facebook are male. They don’t really care about the news I share. They follow me because they want to see beautiful girls.”

It’s worth noting that for most of our sample, we did not specifically seek out women who had experienced harassment. The German research team did intentionally look for women who had experienced harassment for its seven interviews.

Strategies for Dealing with Online Harassment

Of the journalists interviewed, 24 reported developing specific strategies for dealing with online harassment. An American television journalist said she uses Facebook’s word-blocker function on her professional page to prevent words like “sexy,” “hot,” or “boobs” from being posted by users. Another U.S. TV journalist said she deletes comments that seem like come-ons from her professional Facebook page for fear that leaving them up will attract more of the same types of responses.

Other journalists reported changing the way they cover the news to prevent harassment. An online reporter in Taiwan said she focuses on covering positive news so she won’t get attacked for a negative story. After facing extreme harassment at the start of her job, a Latina newspaper reporter in the U.S. is now extra-vigilant about showing multiple sides of a story to prevent complaints that may escalate into abuse. On the other hand, a TV journalist in the U.S. said she tries to avoid details in her stories that she knows will upset people. “Yes, it affects the way I do my stories,” she said. “I am more careful.”

Even journalists who did not report developing a specific strategy to deal with harassment said that they find themselves preparing emotionally for the onslaught after a story is published. “You really do have to build a wall. You really have to have a thick skin,” noted an American journalist. A freelancer in the U.K. said she at times stops engaging after a story runs to avoid the abuse. “If I write for the Sunday newspaper, those comments will appear on my Twitter feed and… it’s thrown my whole weekend,” she noted.

All seven of the German-speaking women we interviewed felt it was important to have colleagues to rely on to talk about harassment they encountered and to help by, for instance, moderating the comments. Most of the women interviewed felt they had little support from their managers and reported that their news organizations offered little training to help them handle the abuse or to prevent it. They worried that if they complained about harassment, they would be labeled as hypersensitive. Online harassment, explained a U.K. video producer, is not really talked about in her newsroom: “We only really discuss it if it’s in a big scale or we’re not really prepared for it.”

METHODOLOGY

We recruited interviews through social media, web searches, email lists, a labor union, and a public service broadcasting complaint office. Our goal was to have a diverse sample in terms of age, race, years of experience, job type, and geographic location. The women we interviewed ranged in age from 21 to 60 years old (with an average age of 34), and had been on the job from 9 months to 35 years at the time of the interviews.

Seventy-five interviews were conducted from spring 2016 to fall 2017, mostly by phone. Each interview was recorded and lasted between 15 and 47 minutes. Participants were asked a series of open-ended questions about their general experiences interacting online as a journalist and about whether they had experienced harassment. They were prompted to provide examples of their experiences and of how the situations affected their work. Participants were also asked what they would like their news organizations to do to improve the situation.

Interviews with journalists in Taiwan were conducted in Mandarin by a Mandarin-speaking researcher, who then translated the interviews into English. Interviews with German- speaking journalists were conducted by German researchers and then translated into English. The rest of the interviews were conducted in English.

To analyze the interviews, researchers listened to the recordings, read through notes, and searched for similarities and differences in what these women were saying. Findings were then categorized into groups of quotes or paraphrases about experiences with online harassment.

SUGGESTED CITATION:

Chen, Gina Masullo, Pain, Paromita, Chen, Victoria Y., Mekelburg, Madlin, Springer, Nina, and Troger, Franziska. (2018, April). Women journalists and online harassment. Center for Media Engagement. https://mediaengagement.org/research/women-journalists

- Edström, M. (2016). The trolls disappear in the light: Swedish experience of sexualized hate speech in the aftermath of Behring Breivik. International Journal for Crime, Justice, and Social Democracy, 5(2), 96-106. [↩]

- Chess, S., & Shaw, A. (2015). A conspiracy of fishes, or, how we learned to stop worrying about #gamergate and embrace hegemonic masculinity. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 59(1), 208-220; Cole, K.K. (2015). “It’s like she’s eager to be verbally abused”: Twitter, trolls, and (en)gendering disciplinary rhetoric. Feminist Media Studies, 15(2), 356-358; Ging, D., & Norman, J.O. (2016). Cyberbullying, conflict management or just messing? Teenage girls’ understanding and experiences of gender, friendship, and conflict on Facebook in an Irish second- level school. Feminist Media Studies, 16(5), 805-821; Perreault, G.P., & Vos, T.P. (2018). The GamerGate controversy and journalistic paradigm maintenance. Journalism, 19(4), 553-569. [↩]

- Chen, G.M., & Pain, P. (2017). Normalizing online comments, Journalism Practice, 11(7), 876-892; Singer, J.B. (2005). The political j-bloggers: “Normalizing” a new medium to fit old norms and practices. Journalism, 6(2), 173- 198. [↩]