Solutions journalism is reporting about responses to entrenched social problems. It examines instances where people, institutions, and communities are working toward solutions. Solutions-based stories focus not just on what may be working, but how and why it appears to be working, or, alternatively, why it may be stumbling. In engagements with more than 30 newsrooms and hundreds of reporters, producers, and editors across the U.S., the Solutions Journalism Network has identified growing interest in the practice of solutions journalism. But what happens when we put this form of reporting to the test: How do citizens respond?

This report outlines the results of a quasi-experiment conducted by the Solutions Journalism Network and the Center for Media Engagement.1 The findings demonstrate that solutions-based reporting may be an effective journalistic tool that serves the needs of both audiences and news organizations and that it has the potential to increase reader engagement.

The Problem

Many journalists report compellingly on the world’s problems, but they regularly fail to highlight and explain responses that demonstrate the potential to ameliorate problems, even when those initiatives show strong evidence of effectiveness.

As a result, people are far more aware of what is wrong with society than what is being done to try to improve it. For many issues that receive ongoing news coverage, what’s most absent is not awareness about the problems but awareness about credible efforts to solve those problems. This omission causes many people to feel overwhelmed and to believe that their efforts to engage as citizens may be futile. Research indicates that when journalists regularly raise awareness about problems without showing people what can be done about them, news audiences are more likely to tune out and deny the message or even disengage from public life.2

Key Findings

The study showed that readers of solutions-based news articles were significantly more likely than non-solutions readers to:

- Have a heightened perceived knowledge and sense of efficacy,

- Feel a stronger connection with news organizations,

- Indicate a desire for potential engagement on an issue.

Implications for Newsrooms

These study results suggest that solutions journalism has the potential to address several major concerns confronting today’s newsrooms. These concerns include: (a) readers’ perceptions, real or imagined, that news is overwhelmingly negative, (b) readers’ feeling that the thoroughness of news reporting is on a downward trend; and (c) the decline in news readership. Each of these concerns, along with solutions journalism’s potential to address them, is explored below.

News Negativity. A prevailing mentality among those who attend to the news is the belief that the majority of news is negative.3 Although some research has noted a few positive aspects of negative news, overall, it is believed that, on balance, it does more harm than good.4 Negative news is a contributor to news fatigue, or a diminished desire to turn to the news.5 The pervasive belief is not only that most news is negative, but that it is, in fact, a reporter’s job to cover negative news. In addition, negative news has been shown to inhibit subsequent information recall.6 In other words, readers of negative news stories are less likely to remember what they have read after encountering negative information.

Today, many news organizations try to balance the negativity of news by including periodic feel-good reporting, such as profiles of “heroes” or people “making a difference.” This approach reveals an implicit bias held by many journalists: a belief that reporting on efforts to solve social problems is of secondary importance to society – a belief that may not be shared by news audiences.7 Given the challenge of balancing the tone of coverage, solutions journalism may offer a more serious-minded approach, providing readers with an entry point to engage more deeply with difficult issues.

News Thoroughness. In 2013, the Pew Research Center’s Project for Excellence in Journalism reported that many people had turned away from a news outlet because of a perceived decline in news quality.8 Specifically, the study asked people if they thought the quantity of news was in decline or the quality of news was in decline. More than 60% of respondents said that news quality was in decline. It is possible that solutions journalism, by giving people a broader view of the news – namely, reporting on problems and responses to those problems – could help to reverse this downward trend.

Readership Decline. Dovetailing with the perception of declining news thoroughness is the finding that those who believe news quality is in decline are also turning away from the news. The same Pew study referenced above asked people the following question: “Have you stopped turning to a particular news outlet because you felt they were no longer providing you with the news and information you were accustomed to?”9 Sixty-five percent of respondents answered “yes.” What this tells us is that if a news outlet is not meeting the needs of the news consumers, these consumers may look elsewhere for their information. Given these study results, we believe that further research is warranted to explore questions about whether solutions journalism has the potential to arrest readership decline – particularly decline associated with news quality – and to drive other changes in audience news consumption, engagement or brand loyalty.

The Study

In the study, a sample of 755 U.S. adults was presented with one of six news articles. The articles reported on three different issues: the effects of traumatic experiences on children in American schools, homelessness in urban America, and a lack of clothing among poor people in India. For each issue, highly similar articles were compared: one that focused exclusively on the problem (non-solution version), and one that included identical reporting on the problem, but added reporting about a potential response to mitigate that problem (solution version). The addition of solutions content was the only difference between the two articles.

The results of this test indicate that solutions-based journalism holds promise in at least three areas: heightening audiences’ perceived knowledge and sense of efficacy, strengthening the connection between audiences and news organizations, and catalyzing potential engagement on an issue.

Heightening audiences’ perceived knowledge and sense of efficacy

The study showed that readers of solutions-based news articles were significantly more likely than non-solutions readers to:

- Say the article seemed different from typical news articles

- Perceive that they gained more knowledge about the issue in the article

- Indicate that they felt better informed about the issue

- Respond that the article had increased their interest in the issue

- Believe they could contribute to a solution to the issue

- Believe that there are effective ways to address the issue

- Say that the article influenced their opinion about the issue

- Indicate that they felt inspired and/or optimistic after reading the article

Strengthening the connection between audiences and news organizations

Solutions readers were more likely than non-solutions readers to indicate that they would:

- Read more articles by the person who authored the article they read

- Read more articles from the newspaper in which their article appeared

- Read more articles about the issue

- Talk to friends or family about the issue

- Share the article they read on social media

Catalyzing potential engagement on an issue

Solutions readers were more likely than non-solutions readers to indicate their desire to:

- Get involved in working toward a solution to the issue

- Donate money to an organization working on the issue

All three shifts, we believe, reflect favorably on audience relationships with news and news organizations. People who think they know more about an issue, share a story with a friend, and/or feel more empowered to act are likely to attach greater value to the news and to feel a stronger attachment to the respective news source.10

Changes in Perceived Knowledge and Sense of Efficacy

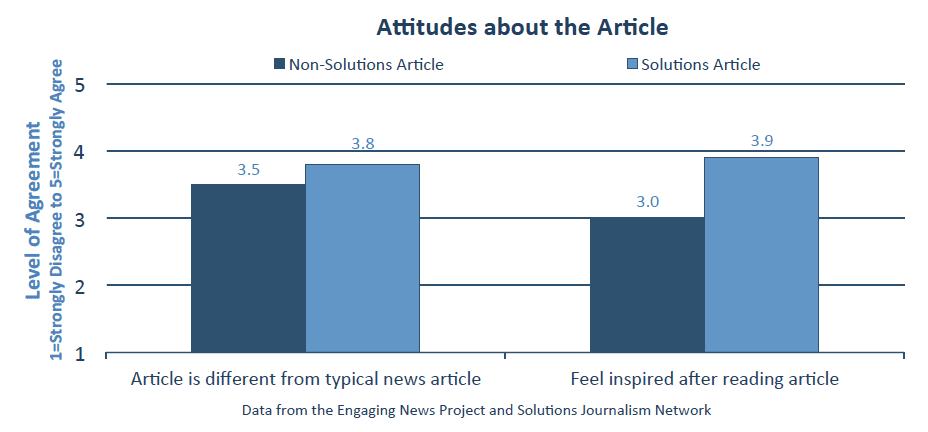

Readers of solutions-based stories expressed more agreement than readers of non-solutions stories that the article they read was different than the typical newspaper article.11 Readers of the solution versions also were more “inspired and/or optimistic after reading the article” than their non-solutions counterparts.12

It should be noted that all of the results reported in this study, and displayed in the accompanying charts, indicate statistically significant differences in responses between solutions and non-solutions article readers. In other words, the chances are extremely slim that the differences in responses are merely based on chance.

Readers also reported differences in how much they believed they knew about the issue, as well as in how interested in and informed they felt about the issue after reading the article.13 In both cases, responses were higher for readers of solutions articles compared to non-solutions articles. Specifically, respondents were asked to agree with the following statements: “The article increased my interest in this topic,” “I feel better informed about the issue discussed in the article,” and “The article did not increase my knowledge of the issue.”14

Readers also reported differences in how much they believed they knew about the issue, as well as in how interested in and informed they felt about the issue after reading the article.13 In both cases, responses were higher for readers of solutions articles compared to non-solutions articles. Specifically, respondents were asked to agree with the following statements: “The article increased my interest in this topic,” “I feel better informed about the issue discussed in the article,” and “The article did not increase my knowledge of the issue.”14

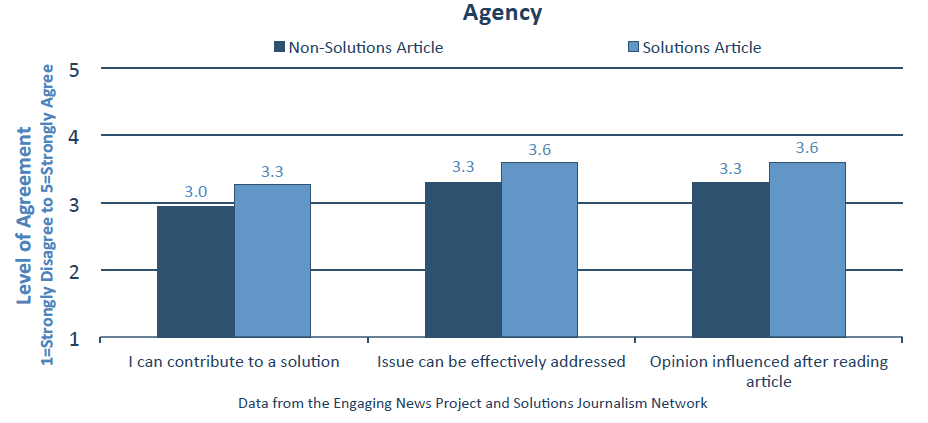

Survey takers also were asked to indicate how they felt about solutions to the issue, including their own ability to contribute to helping solve the problem they read about in their article.15 Respondents noted their agreement with the following statements: “Now that I’ve read this article, I think I can contribute to a solution to this problem;” “Now that I’ve read this article, I think there are ways to effectively address this problem;” and “The article influenced my opinion about the issue.” In all cases, solutions-article readers were more likely to agree with these statements than those who read non-solutions articles.

Survey takers also were asked to indicate how they felt about solutions to the issue, including their own ability to contribute to helping solve the problem they read about in their article.15 Respondents noted their agreement with the following statements: “Now that I’ve read this article, I think I can contribute to a solution to this problem;” “Now that I’ve read this article, I think there are ways to effectively address this problem;” and “The article influenced my opinion about the issue.” In all cases, solutions-article readers were more likely to agree with these statements than those who read non-solutions articles.

Changes in Readers’ Connections to News Organizations

Changes in Readers’ Connections to News Organizations

Respondents were asked how likely they were to: share the article on social media, read more articles by the unnamed author of the article they read, read more articles in the unnamed newspaper in which the article appeared, and read more articles about the particular issue.16 In all instances, survey takers who read solutions articles were significantly more likely to indicate their desire to enact these behaviors than those who read non-solutions articles.

Changes in Citizens’ Engagement in Society

Changes in Citizens’ Engagement in Society

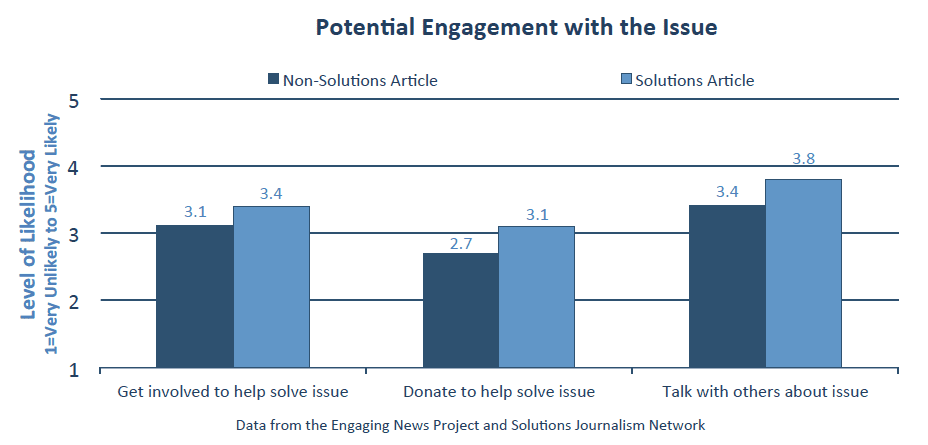

Respondents were asked about their likelihood of getting involved in working toward a solution to the issue, donating to an organization working on the issue, and talking to family and friends about the issue.17 Again, in all cases, those who read solutions articles indicated higher likelihoods than those who read non-solutions articles.

This section’s title includes a key qualifying word, potential, because this study did not measure actual behavior, but instead assessed behavioral intentions. If readers of solutions articles follow suit on such intentions, society may see a benefit due to increased involvement in, funding for, and overall awareness of the issues that are weighing on communities and that are often the focal point of solutions-based reporting.

This section’s title includes a key qualifying word, potential, because this study did not measure actual behavior, but instead assessed behavioral intentions. If readers of solutions articles follow suit on such intentions, society may see a benefit due to increased involvement in, funding for, and overall awareness of the issues that are weighing on communities and that are often the focal point of solutions-based reporting.

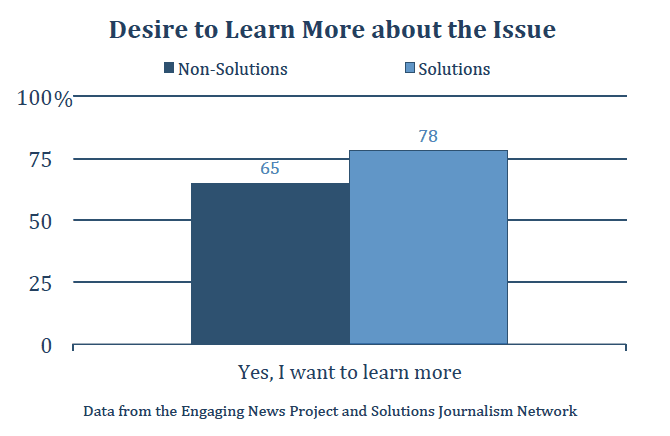

Readers also were asked the following yes/no question at the end of the survey: “Would you like to learn more about how to get involved in finding solutions to this issue?” As was the case in all other instances in this study, readers of solutions-based articles gave significantly more “yes” responses than those reading non-solutions articles.18

These study results suggest that solutions journalism could have significant ramifications for readers and news organizations alike, along with the potential to impact society at large. Compared to readers of non-solutions articles, readers of solutions-based articles not only indicate that they feel more informed by reading solutions stories, but that they want to continue to learn about the issue and were inspired to work toward a solution. For news organizations, the benefits lie in the solutions-readers’ deeper connection to the issues and desire to continue to engage on them, their increased propensity to share what they read, and their desire to read more articles by the author and from the same newspaper. These benefits to individuals, news organizations and, potentially, society, could make solutions journalism a valuable alternative to traditional problem-focused reporting.

These study results suggest that solutions journalism could have significant ramifications for readers and news organizations alike, along with the potential to impact society at large. Compared to readers of non-solutions articles, readers of solutions-based articles not only indicate that they feel more informed by reading solutions stories, but that they want to continue to learn about the issue and were inspired to work toward a solution. For news organizations, the benefits lie in the solutions-readers’ deeper connection to the issues and desire to continue to engage on them, their increased propensity to share what they read, and their desire to read more articles by the author and from the same newspaper. These benefits to individuals, news organizations and, potentially, society, could make solutions journalism a valuable alternative to traditional problem-focused reporting.

Background on Solutions Journalism

Solutions journalism is critical reporting that investigates and explains credible responses to social problems. It delves into the how-to’s of problem-solving, often structuring stories as puzzles or mysteries that investigate questions like: What models are having success reducing the high school dropout rate and how do they actually work?

When done well, the stories can provide valuable insights about how communities may better tackle important problems. As such, solutions journalism can be both highly informative and engaging. News organizations such as The Seattle Times, the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, and the Deseret News, among others, have deployed solutions reporting in an attempt to create a foundation for productive, forward-looking (and less polarizing) community dialogues about vital social issues.

In trying to meet these goals, a solutions journalism story attempts to answer in the affirmative the following ten questions (which serve as a framework, not a set of rules):19

- Does the story explain the causes of a social problem?

- Does the story present an associated response to that problem?

- Does the story refer to problem-solving and how-to details?

- Is the problem-solving process central to the story’s narrative?

- Does the story present evidence of results linked to the response?

- Does the story explain the limitations of the response?

- Does the story contain an insight or teachable lesson?

- Does the story avoid reading like a puff piece?

- Does the story draw on sources that have ground-level expertise, not just a 30,000-foot understanding?

- Does the story give greater attention to the response than to a leader, innovator, or do-gooder?

A good example of solutions journalism will address many, though not necessarily all, of the above questions. Solutions journalism is a form of explanatory journalism that may serve as a form of watchdog reporting, highlighting effective responses to problems in order to spur reform in areas where people or organizations are failing to respond adequately, particularly when better options are available.

Methodology

A survey-based quasi-experimental design was employed to test the effects of solutions journalism. Survey respondents were recruited via the data-collection company, Survey Sampling International, which administered the online survey to a nationwide sample of 1,500 Americans.

Respondents were invited to read “a recent article that appeared in a U.S. newspaper,” and told that after reading the article they would be asked several questions. Respondents were encouraged to read the article thoroughly, as they were told that they would not be able to return to the text of the article after they finished reading. The articles were from the Fixes section of the New York Times. Upon reading the instructions, respondents saw one of six articles. The articles consisted of three topic pairs, where each pair dealt with a different topic. The topics were: (a) the effects of traumatic experiences on children in American schools; (b) homelessness in urban America; and (c) a lack of clothing among poor people in India. Each pair of articles contained a solutions version and a non-solutions version. Other than the presence/absence of solutions content, the articles were identical. The text of each article is located in an appendix at the end of this report.

After reading the article, all respondents were asked to respond to an identical series of survey items. Most of the survey items consisted of 5-point Likert-type scales, where respondents were given a statement and asked to indicate their level of agreement with the statement (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). One closed-ended question was asked (“Would you like to learn more about how to get involved in finding solutions to this issue?), as well as one open-ended item (Did this article influence the way you think about this issue? If so, how?)20

Respondents then were asked whether or not they believed that the author of the story reported on a solution to each problem. This question was used as a manipulation check, to determine whether or not respondents carefully attended to the experimental stimuli. Of the 1,500 respondents who completed the survey, nearly half failed the manipulation check. Those who failed the manipulation check spent significantly less time with the study (Mann-Whitney U=188627.50, p<.001). Data for those who failed the manipulation check were discarded from the statistical analysis. Furthermore, some survey items were counter-valenced in order to detect any respondents who might select responses in a single column for all items (for example, someone who chooses “strongly agree” for every item). All those who gave identically-valenced responses for the nine Likert-type items were removed from the data (n = 55). Lastly, four respondents selected “under 18” in the age question, and as this survey’s target sample was adults, data for these respondents were discarded. The final sample used for data analysis consisted of 755 respondents.

Of those 755 respondents:

- 64% are female

- The median age range is 45-54 years old

- The median education level completed by the respondents is “some college”

- The median yearly income range is $50,000-$75,000

- 34% self-identify as conservative, 31% self-identify as liberal, and 32% indicate that they are neither/middle of the road

- 79% identify themselves as white, 11% identify as black, 6% identify as Asian, and 5% identify as Hispanic

- 9% identify as self-employed, 45% as employed by someone else, 9% as unemployed, 12% as homemakers, 18% as retired, and 7% as students

See full appendix in the full report.

SUGGESTED CITATION:

Curry, Alexander and Hammonds, Keith H. (2014, June). Solutions journalism. Center for Media Engagement. https://mediaengagement.org/research/solutions-journalism/

- This study qualifies as a quasi-experiment, as opposed to a full experiment because we include only data from those who did not fail the manipulation check. Those reading a solutions article were more likely to answer the manipulation check correctly than those reading a non-solutions article. This means that the resulting sample is neither randomly assigned nor randomly selected from the population. To mitigate this concern, we analyzed and controlled for, demographic factors that vary among the conditions. When data analysis is conducted using those who passed and those who failed the manipulation check, (n = 1,443), evidence of significant, albeit more modest, findings remain. In this case, those exposed to a solutions journalism article are significantly more likely than their non-solutions counterparts to feel that they had gained new knowledge about the topic from reading the article, indicate that they felt inspired and/or optimistic after reading the article, and believe that there are effective ways to address the issue. [↩]

- Associated Press and the Context-Based Research Group, A new model for news; Benesh, S. (1998). The rise of solutions journalism. Columbia Journalism Review; Feinberg, M., & Robb, W. (2010). Apocalypse soon? Dire messages reduce belief in global warming by contradicting just-world beliefs. Psychological Science, 22(1), 34-38; Glassner, B., (2004). Narrative techniques of fear-mongering. Social Research: An International Quarterly, 71(4), 819-826; Merritt, D. (1998). Public journalism and public life: Why telling the truth is not enough. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Patterson, T. (2002). Why is the news so negative these days? George Mason University History News Network, http://hnn.us/article/1134, Pauly, J. J. (2009). Is journalism interested in resolution, or only in conflict? Marquette Law Review, 93(1), 7-23. [↩]

- See, for instance, Potter, D., & Gantz, W. (2000). Bringing viewers back to local TV news. Civic Catalyst Newsletter, Pew Center for Civic Journalism;Foerstel, H. N. (2001). From Watergate to Monicagate: Ten controversies in modern journalism and media. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. [↩]

- For example, see: Baumgartner, S. E., & Wirth, W. (2012). Affective priming during the processing of news articles. Media Psychology, 15(1), 1–18; Grabe, M. E. (2006). Hard wired for negative news? Gender differences in processing broadcast news. Communication Research, 33(5), 346–369. [↩]

- Associated Press and the Context-Based Research Group, A new model for news. [↩]

- Biswas, R., Riffe, D., & Zillmann, D. (1994). Mood influence on the appeal of bad news. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 71(3), 689–696. See also Newhagen, J. E., & Reeves, B. (1992). The evening’s bad news: Effects of compelling negative television news images on memory. Journal of Communication, 42(2), 25–41. [↩]

- Associated Press and the Context-Based Research Group, A new model for news; Benesh, The rise of solutions journalism. [↩]

- Enda, J., & Mitchell, A. (2014). Americans show signs of leaving a news outlet, citing less information. The Pew Research Center’s Project for Excellence in Journalism. The State of the News Media 2013: An Annual Report on American Journalism. Retrieved from http://stateofthemedia.org/2013/special-‐reports-landing-page/citing-reduced-quality-many-americans- abandon-news-outlets/ [↩]

- Enda & Mitchell, Americans show signs of leaving a news outlet. [↩]

- Associated Press and the Context-Based Research Group. (2008). A new model for news: Studying the deep structure of young-adult news consumption. [↩]

- For most questions, survey takers were asked to indicate their level of agreement with certain statements. For example, one set of questions was put to survey takers as follows: “Based on your overall response to this article, rate your level of agreement with the following statements: The article increased my interest in this topic.” Response options were as follows: Strongly disagree, disagree, neutral, agree, and strongly agree. In four instances, statistical analyses revealed that responses were influenced not only by exposure to the solutions v. non-solutions articles but also by the topic of the articles. Those four instances include responses to the following statements: the article is different than the typical article; there are ways to effectively address the issue; I feel more informed after reading the article; and Likelihood of reading more articles about the issue. For each of these questions, the differences between solutions and non-solutions articles appear for two issues (trauma, homeless), but not for the third (clothing). While the topic differences affected responses, responses were significantly affected by the presence or absence of the solutions-based article. The variable Article is Different was significantly different for solutions vs. non-solutions journalism F(1, 717) = 14.69, p < .001, controlling for age, gender, employment, and race. [↩]

- The variable Inspired was significantly different for solutions vs. non-solutions journalism F(1, 717) = 160.62, p < .001, controlling for age, gender, employment, and race. [↩]

- The variable Knowledge was significantly different for solutions vs. non-solutions journalism F(1, 717) = 8.16, p < .01, controlling for age, gender, employment, and race; the variable More Interested was significantly different for solutions vs. non-solutions journalism F(1, 717) = 11.59, p = .001, controlling for age, gender, employment, and race; and the variable Feel Informed was significantly different for solutions vs. non-solutions journalism F(1, 717) = 19.01, p < .001, controlling for age, gender, employment, and race. [↩]

- The knowledge item was phrased in this way in order to help determine if some respondents were clicking through survey items without reading the statements. This, and one other similarly phrased item, helped us detect 10 respondents who most likely clicked on responses without reading the accompanying statements. As discussed in the methodology section, data from these 10 respondents were not used in the statistical analyses. [↩]

- The variable Contribute was significantly different for solutions vs. non-solutions journalism F(1, 717) = 19.13, p < .001, controlling for age, gender, employment, and race; the variable Effective Solutions was significantly different for solutions vs. non-solutions journalism F(1, 717) = 23.10, p < .001, controlling for age, gender, employment, and race; and the variable Influenced Opinion was significantly different for solutions vs. non-solutions journalism F(1, 717) = 15.13, p < .001, controlling for age, gender, employment, and race. [↩]

- The variable Share Article was significantly different for solutions vs. non-solutions journalism F(1, 717) = 11.88, p = .001, controlling for age, gender, employment, and race; for the variable Read Article, was significantly different for solutions vs. non-solutions journalism F(1, 717) = 18.02, p < .001, controlling for age, gender, employment, and race; for the variable Read News, was significantly different for solutions vs. non-solutions journalism F(1, 717) = 16.94, p < .001, controlling for age, gender, employment, and race; and for the variable Read Issue, was significantly different for solutions vs. non-solutions journalism F(1, 717) = 17.23, p < .001, controlling for age, gender, employment, and race. [↩]

- The variable Involved was significantly different for solutions vs. non-solutions journalism F(1, 717) = 17.58, p < .001, controlling for age, gender, employment, and race; for the variable Donate, was significantly different for solutions vs. non-solutions journalism F(1, 717) = 17.98, p < .001, controlling for age, gender, employment, and race; and for the variable Talk Friends, was significantly different for solutions vs. non-solutions journalism F(1, 717) = 16.13, p < .001, controlling for age, gender, employment, and race. [↩]

- The variable Learn More was significantly different for solutions vs. non-solutions journalism F(1, 717) = 12.91, p < .001, controlling for age, gender, employment, and race. [↩]

- See the Solutions Journalism Network’s webinar for Poynter’s News University. [↩]

- Responses to the open-ended item were analyzed by the Solution Journalism Network’s Rikha Sharma Rani, using a Stanford University-developed sentiment analysis program called NaSent. Results from NaSent analysis indicated that responses were more positive and less negative for those who read the solutions version of the homelessness and clothing-in-India articles, as well as less negative for those who read the solutions version of the trauma article. [↩]