SUMMARY

The Center for Media Engagement in the U.S. teamed up with researchers from Erasmus University in the Netherlands and NOVA University in Portugal to figure out how people from these three countries define hateful speech and whether they differentiate it from profanity.

The results offer global guidance for social media platforms and news outlets on how to effectively create moderation guidelines that limit confusion about why certain posts and comments are removed while others are allowed. Based on the results we suggest that:

- Content moderation guidelines should be tailored to the culture of specific countries. For example, platforms in Portugal and the Netherlands should highlight their definitions of hate speech more prominently because that distinction is not clear for users in those countries.

- Users should be informed about the definitions of profanity or hateful speech when they agree to use the platform, so they are clear about what is permitted.

- Users should be told what was wrong with the content if it is removed, so they will learn how profanity or hateful speech is defined on that platform.

THE PROBLEM

Social media platforms and news outlets want online comment sections to be productive spaces for discussion, so they use content moderation to remove hateful speech. But there is no universal global definition of hate speech. Under European law, hate speech is defined as inciting hatred or perpetuating stereotypes about specific groups based on characteristics such as race, gender, or sexual orientation.1 However, the European approach has not been adopted worldwide, and U.S. law has no official hate speech definition.

The Center for Media Engagement in the U.S. teamed up with researchers from Erasmus University in the Netherlands and NOVA University in Portugal to figure out how people from these three countries define hateful speech and whether they differentiate it from profanity. We conducted an experiment where we showed internet users from the three countries a series of social media posts, and asked them to rate the hatefulness and degree of profanity of each post.2 This project was funded by Facebook. All research was conducted independently.

KEY FINDINGS

- Overall, Americans had a clearer perception of what they considered hate speech than Europeans. This is notable because the U.S. does not have a legal definition of hate speech, while some European countries do.3

- Americans saw coarse language or swear words as substantially less hateful than derogatory comments about immigrants or comments that incited violence.4 They also saw comments with swear words as significantly more profane than comments that incited violence or targeted specific vulnerable groups.5

- For participants in both European countries, the distinction between profanity and hatefulness was less clear. In the Netherlands, participants perceived posts with profanity as both more profane6 and more hateful7 than comments that incited violence or attacked specific vulnerable groups.

- This line between hate speech and profanity was particularly blurry for participants in Portugal. Participants there rated comments as equally profane or hateful, regardless of whether they contained swear words or derogatory comments about specific vulnerable groups.8

IMPLICATIONS

Our findings offer global guidance for social media platforms and news outlets on how to effectively create moderation guidelines that limit confusion among users about why certain posts and comments are removed while others are allowed. We suggest that:

- Content moderation guidelines should be tailored to the culture of specific countries. For example, platforms in Portugal and the Netherlands should highlight their definitions of hate speech more prominently because that distinction is not clear for users in those countries.

- Users should be informed about the definitions of profanity or hateful speech when they agree to use the platform, so they are clear about what is permitted.

- Users should be told what was wrong with the content if it is removed, so they will learn how profanity or hateful speech is defined on that platform.

THE EXPERIMENT

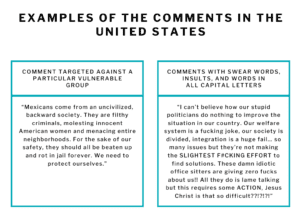

A total of 304 participants9 from the U.S., the Netherlands, and Portugal were randomly assigned to view either five posts that contained derogatory barbs against immigrants or incitements of violence against these immigrants or five posts that were not targeted at a specific vulnerable group and that contained swear words, name-calling, or words in all capital letters to indicate shouting.10 All posts appeared as if they were posted to a social media platform like Facebook and were translated into Dutch or Portuguese for participants in those countries. Posts in one experiment group referred to vulnerable minority populations in each country – “Mexicans” in the U.S. experiment, “refugees” in the Dutch experiment, and “Brazilian migrants” in the Portuguese experiment.11

WHAT WE FOUND

Participants answered two questions about each comment they viewed regarding how profane they found it and how hateful they found it. Both questions were rated on a 1 to 5 scale with a higher number meaning the comment was seen as more hateful or more profane.12

We found that:

- In all countries, posts were seen as similarly profane. However, only participants from the U.S. made a clear distinction between expressions they considered profane and expressions they considered hateful. This suggests Americans think of hate speech and profanity as distinct concepts.

- In both European countries, perceptions of profanity and hatefulness overlapped. For Dutch participants, comments containing insults, all caps, and swear words were perceived as profane and as more hateful than comments that attacked specific vulnerable groups.

- Portuguese participants rated comments that targeted specific vulnerable groups and comments that contained profanity as equally hateful and profane. Overall, the Portuguese seemed to make the least distinctions between hate speech and profanity. They perceived profane language as more hateful than

American participants13 and expressions targeting specific vulnerable groups as more hateful than Dutch participants.14

METHODOLOGY

The experiment was conducted on March 5 and 6, 2020, using Qualtrics. Our sample was recruited through Dynata, an online survey company. A total of 149 people from the U.S., 93 from the Netherlands, and 62 from Portugal participated.15 Participants accessed the survey experiment through an online link and completed it on their own computers.

SUGGESTED CITATION:

Weber, Ina, Laban, Aquina, Masullo, Gina M., Gonçalves, João, Torres da Silva, Marisa, and Hofhuis, Joep. (September, 2020). International perspectives on what’s considered hateful or profane online. Center for Media Engagement. https://mediaengagement.org/research/perspectives-on-online-profanity

- ECRI. (2016). ECRI General Policy Recommendation No. 15 on combating hate speech. Strasbourg: Council of Europe. [↩]

- For each comment, participants rated on a 1 to 5 scale, “To what extent would you say does this post contain profanity?” to measure profaneness and “To what extent would you say does this post contain hate speech?” to measure hatefulness. Rating were done for five comments that contained swear words or insults, and scores were averaged together for a composite score. Ratings were also done for five comments that incited violence or attacked a specific vulnerable group, and these scores were averaged together for a composite score. [↩]

- ECRI. [↩]

- All statistical tests were conducted on the composite scores. An independent t test (t (147) = -2.33), showed that U.S. participants rated comments that incited violence or attacked specific vulnerable groups (M = 4.02) as significantly more hateful than comments with profanity (M = 3.58, p = .02) [↩]

- An independent t test (t (133.61) = 6.69), showed that U.S. participants rated comments with swear words (M = 3.83) as significantly more profane than comments that incited violence or attacked specific vulnerable groups (M = 2.51, p < .001) [↩]

- An independent t test (t (86.47) = 7.92) showed that Dutch participants rated comments with swear words (M = 4.22) as significantly more profane than comments that incited violence or attacked specific vulnerable groups (M = 2.49, p < .001). [↩]

- An independent t test (t (76) = 2.55) showed that Dutch participants rated comments with swear words (M = 4.35) as significantly more hateful than incited violence or attacked specific vulnerable groups (M = 3.82, p = .02). [↩]

- An independent t test (t (60) = -1.15) showed that Portuguese participants rated comments with swear words (M = 4.14) as equally profane as comments that incited violence or attacked specific vulnerable groups (M = 3.85, p = .26). They also rated comments that incited violence or attacked specific vulnerable groups (M = 4.48) as equally hateful as comments with swear words (t (60) = -1.51, M = 4.18, p = .14). [↩]

- Erasmus University in the Netherlands granted Ethics Review Board approval for the project on February 3, 2020. Institution- al Review Board approval for the project was granted by The University of Texas at Austin on February 26, 2020. [↩]

- We based these categories on definitions of hateful speech from ECRI. (2016). ECRI General Policy Recommendation 15 on combating hate speech. Strasbourg: Council of Europe; Article 19. (2015). Hate speech explained. A toolkit: London; Gagliardone, I., Gal, D., Alves, T., & Martinez, G. (2015). Countering online hate speech. Paris: UNESCO. Our profanity condition was based on the conceptualization of incivility from Chen, G.M. (2017) Online incivility and public debate: Nasty talk. Palgrave Macmillan and Muddiman, A. (2017). Personal and Public Levels of Political Incivility. International Journal of Communication, 11, 3182–3202. [↩]

- For Portugal, we chose Brazilian migrants because Brazilians have a long history of immigrating to Portugal, and they constituted the largest group of immigrants in Portugal in 2019 (Silva, M.T. (2019). Fact sheet Portugal. Country report on media and migration. New Neighbours. Retrieved from: https://newneighbours.eu/research/). For the Netherlands, we chose refugees because this minority group has affected public opinion strongly even though numbers of incoming refugees have declined since a peak in 2015 (d’Haenens, L., Joris, W., & Heinderyckx F. (Eds.). (2019). Images of immigrants and refugees in Western Europe. Media representations, public opinion, and refugees’ experiences. Leuven: University Press). For the U.S., Mexicans were used because the U.S. has had long-time tension over immigration from Mexico that heightened during the presidency of Donald J. Trump. [↩]

- Ratings were done separately for each country. [↩]

- Results of an ANOVA with Tukey post hoc tests for hatefulness of comments that contained swear words (F (2, 140) = 9.9, p < .001, partial η2 = .12) showed that Portuguese participants rated these comments as significantly more hateful (M = 4.18) than U.S. participants (M = 3.58, p = .02), but not significantly different than Dutch participants (M = 4.35, p = .74). Post hoc tests also showed Dutch and American ratings were different, p < .001. [↩]

- Results of an ANOVA with Tukey post hoc tests for hatefulness of comments that attacked a specific vulnerable group or incited violence, (F(2, 158) = 3.51, p = .03, partial η2 = .04) showed that Portuguese participants rated these comments as significantly more hateful (M = 4.48) than those in the Netherlands (M = 3.82, p = .03) but not when compared to U.S. participants (M = 4.02, p = .12). Ratings from participants in the Netherlands were not significantly different from those in the U.S. (p = .60). [↩]

- Initially, there were 334 participants in total, but data from 30 participants had to be removed because they completed the survey too quickly to be reliable. [↩]