Headlines are snapshots of the news, designed to summarize, provoke, question, and, often, entertain. As many news outlets shift resources to digital forms of journalism, the function of news headlines has gained renewed importance. Amid a nearly limitless amount of news choice, “clickbait” headlines attempt to entice and engage news audiences.

The Problem

How different headlines influence individuals has been a long-term concern among journalists and academics. Past research has found that headlines can change perceptions of a criminal suspect’s supposed guilt, influence how individuals assess political candidates, and affect comprehension and memory of news articles.1

How headlines are worded and the issues headlines discuss also can affect individuals. In an earlier Center for Media Engagement white paper on headlines, Research Associate Alex Curry and Director Talia Stroud investigated how solutions-oriented headlines are received by audiences. These headlines mention the possible solutions to the problems facing communities. In general, headlines that discuss “solutions” lead to more digital clicks compared to non-solutions-based headlines.

The influence of headlines on perceptions of news events also can vary based on the issue discussed.2 For instance, prior research has found that headlines can influence feelings about political candidates as well as change perceptions of racial violence.3 In science contexts, however, headlines have been found to have little effect on attitudes related to genetic determinism (e.g. “gene causes high blood pressure”).4 Although headlines can influence subsequent attitudes and beliefs, effects also can be highly contextualized based on the news issue.

Key Findings

In summary, this research finds:

- Question-based headlines lead to more negative attitudes about the headline and more negative expectations for the associated news story compared to traditional headlines

- Forward-reference headlines did not lead to different reactions, expectations, or anticipated engagement compared to traditional headlines

- Types of headlines and policy issues should be paired carefully; question-based headlines about Congress yielded the most negative reactions.

- News source brand (USA Today, BuzzFeed, and Fox News/MSNBC) matters for headline and story perceptions

Implications for Newsrooms

News outlets are investing resources in producing and testing different types of headlines. These headlines often communicate varying degrees of certainty about the associated news article in order to generate clicks. Our findings show that the amount of uncertainty framed in a news headline is noticed by and has meaningful effects for individuals.

Headlines styled as questions led to the most negative reactions compared to traditional and forward-reference headlines, especially when paired with a topic the participants found particularly unappealing. Forward-reference headlines, however, did not lead to more negative reactions compared to traditional headlines.

Additionally, news source matters. People reacted more positively toward a legacy news brand but anticipated engaging slightly more with a digital news brand. One possible explanation for these engagement findings may be the behavioral habits individuals are developing toward digital news, a possibility that warrants continued study by practitioners and researchers.

We find that the type of headline used matters above and beyond source and issue factors, differences that were small but still quite meaningful at times. The modest effects are important because headline type is something that journalists and the news organizations for which they work can alter at any time, unlike a newsworthy topic or the source attached to their headlines.

As news outlets attempt to garner competitive advantage in a changing media landscape, even small influences can lead to substantive changes both commercially within a news organization as well as democratically. The results show that the type of headline and the source of the headline can affect whether a person reacts more or less positively to a news product and intends to engage with that product in the future.

The Study

In this study, we tested whether headlines written using varying levels of uncertainty prompt different reactions to political news. Specifically, we determine whether traditional, forward-reference or question-based headlines elicit negative reactions to a headline, negative expectations about a news article, and fewer intentions to engage with the news article. Each headline style illustrates different degrees of certainty.

Traditional news headlines provide an overview of the main idea in an inverted pyramid-structured news story.5 News editors and writers compose these headlines to be short and clear.6 In the process, the news writing evinces a relatively certain tone.7

“‘Brexit’ Vote Reflects How Diversity Adds to E.U. Pain”

Forward-reference headlines create more uncertainty about information in a story compared to traditional headlines. These clickbait-type headlines are designed to generate traffic to news articles by emphasizing unknown information.8

“How Far-Right Groups Are Using Orlando to Turn LGBT People Against Muslims and Immigrants”

Question-based headlines are another type of clickbait-style headline designed to create uncertainty by posing a question about information contained in a news story. The question headline is then answered by reading the remainder of the story.

“How ‘Kooky’ is Trump’s Keystone Pipeline Proposal?”

To test these headlines, we conducted an experiment with 2,057 U.S. adults during January 2016. We varied the three types of headlines (traditional, forward reference, or question-based) participants saw in the experiment alongside the brand of a news source (USA Today, BuzzFeed, and Fox News/MSNBC) and the policy issue (the economy, immigration, and the U.S. Congress). Participants saw one headline type, responded to questions about that headline, then saw the next headline. Each participant evaluated 3 headlines.

Result #1: Headlines Framed As Questions Lead to More Negative Outcomes

We tested effects of headline type by asking:

- Whether participants had generally positive or negative thoughts about the headline using nine questions about whether the headline was informative/uninformative, clear/unclear, etc.

- Whether participants had positive or negative expectations for the news article using seven questions about whether they thought the article would be informative/uninformative, clear/unclear, etc.

- How likely participants would be to engage with the headline using six questions about whether participants would like or favorite, share or Tweet, etc.

We found that:

- Compared to traditional headlines, people had slightly more negative reactions toward the question-based headline.9

- People had slightly more negative expectations of the news articles that would follow question-based headlines compared to news articles that would follow traditional headlines.10

- Question-based headlines slightly decreased anticipated engagement with the news compared to traditional news headlines.11

- Reactions to forward-reference headlines did not differ from traditional headlines.12

In sum, people responded more positively overall to traditional headlines compared to question-based headlines. Forward-reference headlines did not change opinions relative to traditional news headlines. Notably, the differences between traditional headlines and question-based headlines were modest, but they occurred even when taking the source of the headline and the topic of the headline into account.

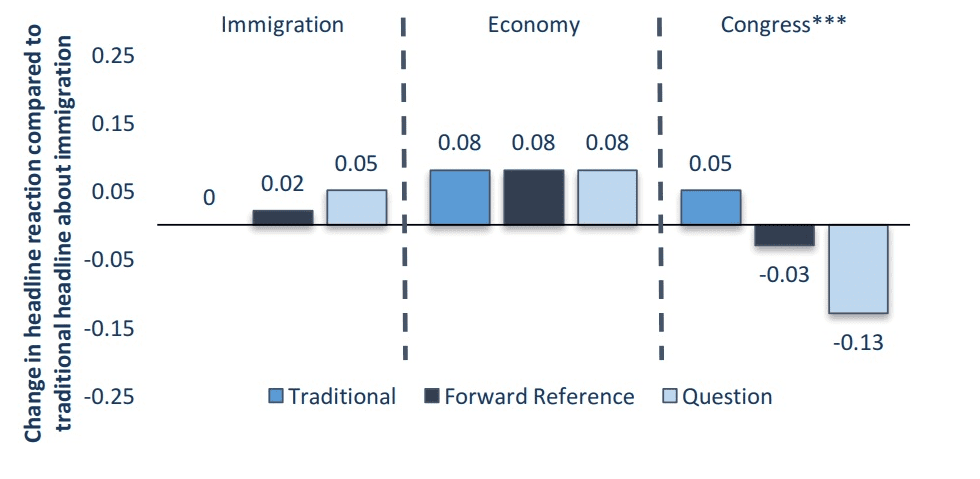

Result #2: Types of Headlines Should Be Carefully Paired with Particular Policy Issues

To explore whether the effects of the headlines were influenced by the topic of the headline, we tested the headline types across three different topics: immigration policy, the economy, and the U.S. Congress.

We found that, compared to a traditional headline that covered immigration, individuals reacted strongly to a headline about Congress that was written as a question. Whereas a traditional headline about Congress produced a positive reaction toward the headline, a question-based headline about Congress produced a negative reaction.13

Affective Reactions to Headlines Across Issue

Change in headline reaction compared to traditional headline about immigration

Data from Center for Media Engagement

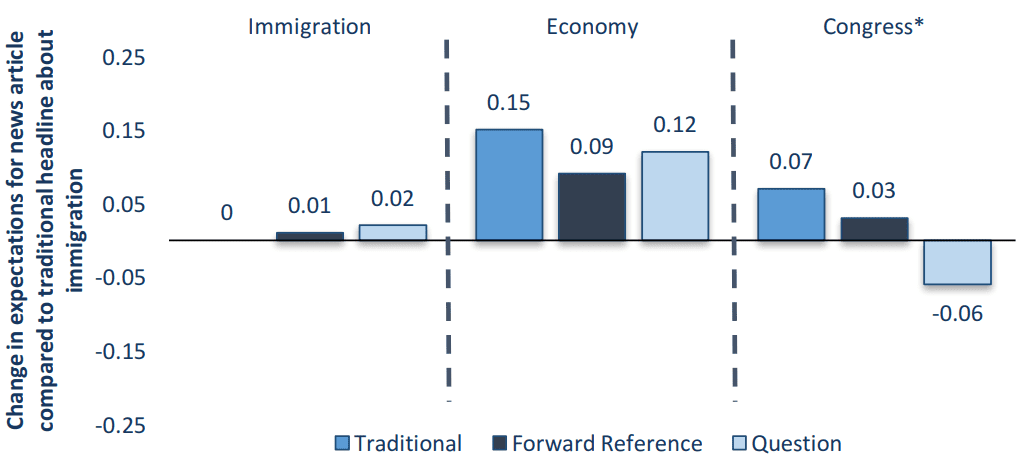

Similarly, a headline about Congress and written as a question prompted the most negative expectations about a news article that would follow the headline, especially compared to a traditional headline about Congress.14

Expectations for News Article Across Issue

Change in expectations for news article compared to traditional headline about immigration

Data from Center for Media Engagement

The topic did not always affect individuals’ reactions to news headlines. However, when the question headline was matched with Congress – which was the most negatively received topic in our study – the combination led to the most negative responses to the headline.

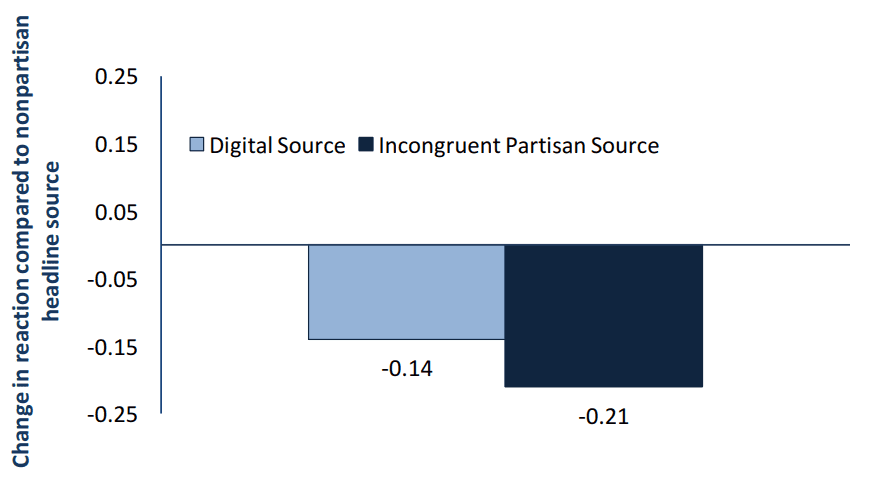

Result #3: News Source Brand Matters for Headline and Story Perceptions

As legacy and digital-based news outlets experiment with new ways of headline writing, different styles of headlines have become characteristic of particular news platforms. Legacy-based news media outlets, like The New York Times, use more traditional styles of headlines.15 Digital-based outlets, like BuzzFeed and Upworthy, include a mixture of headline styles.

We examined whether the source attached to the headline affected reactions to the headlines, expectations of the news article that would follow the headline, and anticipated engagement with the headline. Specifically, we compared the appeal of a nonpartisan news source (USA Today), a digital news source (BuzzFeed), and a news source that was incongruent with a person’s partisanship (either Fox News or MSNBC). We found that:

Compared to the headline from USA Today, headlines from BuzzFeed or a partisan news source (Fox News, MSNBC) prompted more negative reactions from participants.16

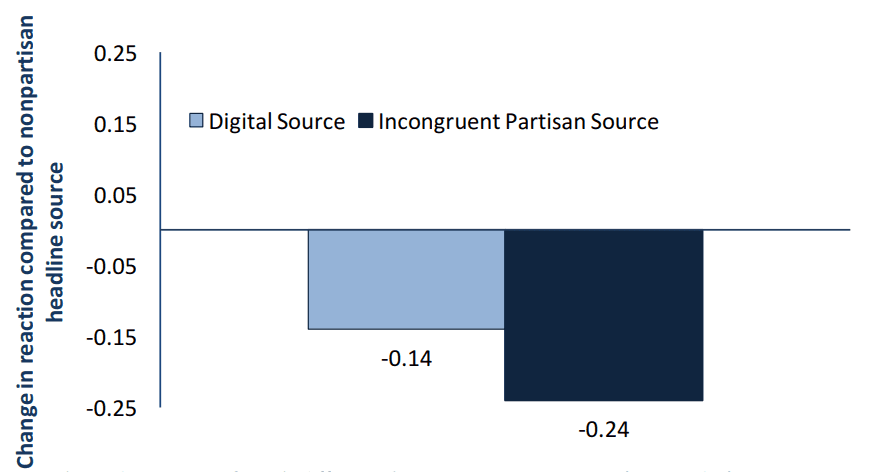

Reaction to Headline Across News Source

Change in reaction compared to nonpartisan headline source

Data from Center for Media Engagement

Compared to the headline from USA Today, headlines from BuzzFeed or a partisan news source (Fox News, MSNBC) prompted more negative expectations about a news article that would follow the headline.17

Expectations for Article Across News Source

Change in reaction compared to nonpartisan headline source

Data from Center for Media Engagement

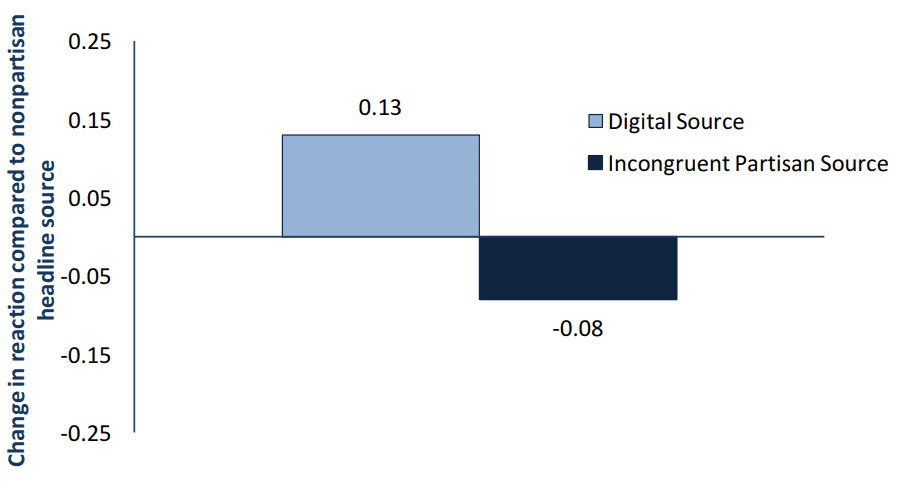

Compared to headlines connected to USA Today, headlines connected to BuzzFeed prompted slightly more anticipated future engagement whereas incongruent partisan news source prompted less.18 19

Anticipated Behaviors Across News Source

Change in reaction compared to nonpartisan headline source

Data from Center for Media Engagement

Overall, people reacted not only to the type of headline but also to the source of the headline. Across headline type, a legacy nonpartisan news source prompted more positive reactions than digital and incongruent partisan sources, but a digital news source was modestly more likely to encourage people to engage with the news in the future.

Methodology

Survey respondents were recruited from Survey Sampling International between January 18 and January 26, 2016. Just over 2,000 participants (n=2,057) took part in the experiment. Participants from various demographics were recruited. Although not nationally representative, the sample matched the demographic information of Internet users according to the Pew Research Center’s most recent findings. Participants were U.S. residents who were at least 18 years old.20

| SSI Sample | Pew Research Center | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 47% | 48% |

| Female | 53% | 52% |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| White, non-hispanic | 73% | 74% |

| Black, non-hispanic | 13% | 13% |

| Other | 13% | 13% |

| Age | ||

| 18-29 | 24% | 24% |

| 30-49 | 38% | 38% |

| 50-64 | 25% | 25% |

| 65+ | 12% | 13% |

| Education | ||

| HS Grad or less | 25% | 36% |

| High school | 42% | 33% |

| College + | 34% | 31% |

| Income | ||

| <$30K | 29% | 31% |

| $30K to <$50K | 24% | 20% |

| $50K to <$75K | 18% | 16% |

| >$75K | 30% | 33% |

Participants began the study by answering questions about their partisan identification and completing a series of distractor activities designed to minimize the pre-test questions priming partisanship (i.e. they sorted images of public figures into categories of either journalists or celebrities). After completing the pre-test items, individuals were randomly assigned to three experimental news headlines. Participants were exposed to one headline, responded to questions about that headline, then saw the next headline. The random assignment to three headlines followed a 3(headline type) x 3(issue) x 3(source) Greco-Roman Latin Squares design.21 This design allowed all individuals to see one headline from each of the headline types (traditional, forward reference, question) without repeating the same topic and news source. Each participant was exposed to three headline type-policy issue-news source pairings. In all, there were 27 combinations of headlines.

We tested the effects of three types of headlines: traditional, forward reference, and question. The traditional headlines provided the main thrust of a story in much the same way as traditional headlines in print newspapers (e.g., American Economy About to Boom Again). The forward-reference headlines were written as declarative sentences, like the traditional headline, but made clear in the headline that some major part of the news story was left out of the headline (e.g., Why the American Economy is About to Boom Again). Finally, the question-based headline was written in the form of a question, rather than a statement. Like the forward-reference headline, the question hinted that there was more to the story than what was contained in the headline (e.g., Is the American Economy About to Boom Again?).

We used three policy issues in our headlines. The three issues were chosen using responses from the November 2015 Gallup poll that asked respondents what they thought was the most important problem facing the U.S. The top responses were the economy, immigration, and dissatisfaction with government (i.e. the U.S. Congress).

Finally, we varied the news sources seen by participants by presenting a logo next to each headline. Participants were exposed to one traditionally nonpartisan source (USA Today), one digital source (BuzzFeed), and one source with an incongruent political party’s lean (either Fox News or MSNBC). Those who identified as Democrats were shown Fox News and Republicans were shown MSNBC. Nonpartisan identifiers were not shown a partisan headline.

Example Headline Stimulus

We examined how individuals reacted to the headlines presented, the expectations survey respondents developed of a hypothetical news article that might follow each headline, and likelihood of future news engagement.

To measure reactions to the headlines, participants responded to a series of nine 5-point semantic differential items. Participants were asked to complete the statement “The headline you just read is…” by marking somewhere in between each of the following: uncivil/civil, untrustworthy/trustworthy, partisan/nonpartisan, uninformative/informative, boring/entertaining, inappropriate/appropriate, confusing/clear, silly/serious, not credible/credible.22

To measure the expectations participants had for the article that would come after each headline, participants responded to seven 5-point semantic differential items. Survey respondents completed the statement “Based on the information you have been given, do you expect the article following this headline to be…” by marking somewhere in between each of the following: uncivil/civil, untrustworthy/trustworthy, partisan/nonpartisan, uninformative/informative, boring/entertaining, inappropriate/appropriate, confusing/clear.23

To measure participants’ interest in engaging with the hypothetical news article based on the headline alone, participants responded to six 5-point Likert-type items (Very Unlikely = 1 to Very Likely = 5) assessing whether they would engage in the following behaviors: read the article, “Like” or “Favorite” the article via a social media site, share or “Tweet” the article via a social media site, leave a comment in the comment section, talk to someone about the article, or pay a small fee for the article.24

Demographics for our sample were matched to the population of U.S. internet users, as determined using frequencies provided by Pew Research Center. The Pew Research data asked a combined race/ethnicity question where we asked two separate questions. We recalculated the racial composition of the Pew data for non-Hispanic identifiers to compare with our data.

SUGGESTED CITATION:

Scacco, Joshua and Muddiman, Ashley. (2016, August). Investigating the influence of “clickbait” news headlines. Center for Media Engagement. https://mediaengagement.org/research/clickbait-headlines

- Tannenbaum, P. H. (1953). The effect of headlines on the interpretation of news stories. Journalism Quarterly, 30, 189-197.; See also: Geer, J. G., & Kahn, K. F. (1993). Grabbing attention: An experimental investigation of headlines during campaigns. Political Communication, 10, 175–91.; Ecker, U. K. H., & Lewandowsky, S. (2014). The effects of subtle misinformation in news headlines. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 20, 323-335. [↩]

- Condit, C. M., Ferguson, A., Kassel, R., Thadhani, C., Gooding, H. C., & Parrott, R. (2001). An exploratory study of the impact of news headlines on genetic determinism. Science Communication, 22, 379–95.; See also: Pfau, M. R. 1995. Covering urban unrest: The headline says it all. Journal of Urban Affairs, 17, 131–41.; Geer & Kahn, 1993; Tannenbaum, 1953. [↩]

- Geer & Kahn, 1993; Pfau, 1995. [↩]

- Condit et al., 2001. [↩]

- Andrew, B. C. (2007). Media-generated shortcuts: Do newspaper headlines present another roadblock for low-information rationality? The Harvard International Journal of Press/Politics, 12, 24-43. [↩]

- Bronzan, N. C. (2015, June 22). Headline writing with an NYT guru. Retrieved from https://www.propublica.org/podcast/item/headline-writing-with-nyt-guru; See also: Dor, D. (2003). On newspaper headlines as relevance optimizers. Journal of Pragmatics, 35, 695–721. [↩]

- Hart, R. P. (2000). Campaign talk: Why elections are good for us. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.; See also Rubin, V. L. (2010). Epistemic modality: From uncertainty to certainty in the context of information seeking as interactions with texts. Information Processing and Management, 46(5), 533–540. [↩]

- Blom, J. N., & Hansen, K. R. (2015). Click bait: Forward-reference as lure in online news headlines. Journal of Pragmatics, 76, 87-100. [↩]

- We ran a fixed effects linear model predicting affective reactions to a news headline. The model included the headline source, topic of the headline, and the type of headline as predictor variables. We held the effects of the individual fixed. Compared to the traditional headlines (included as the reference group), reactions to the forward-reference headlines were more negative (B = -0.02; SE = -0.02; p > .05), though not significantly so, and reactions to the question headlines were significantly more negative (B = -0.04; SE = -0.02; p < .05). [↩]

- We ran a fixed effects linear model predicting affective expectations for a news article that would follow the headlines. The model included the headline source, topic of the headline, and the type of headline as predictor variables. We held the effects of the individual fixed. Compared to the traditional headlines (included as the reference group), expectations for articles following the forward reference headlines were more negative (B = -0.03; SE = -0.02; p > .05), though not significantly so, and expectations for articles following the question headlines were significantly more negative (B = -0.05; SE = -0.02; p < .05). [↩]

- We ran a fixed effects linear model predicting anticipated engagement with the headline and news story. The model included the headline source, topic of the headline, and the type of headline as predictor variables. We held the effects of the individual fixed. Compared to the traditional headlines (included as the reference group), forward-reference headlines prompted fewer anticipated behaviors (B = -0.01; SE = -0.02; p > .05), though not significantly so, and the question-based headlines prompted significantly fewer anticipated behaviors (B = -0.03; SE = -0.02; p < .05). [↩]

- See endnotes 5, 6, and 7 for the statistical details. [↩]

- We ran a second fixed effects linear model predicting affective expectations for a news article that would follow the headlines. The model included the headline source, topic of the headline, and the type of headline as predictor variables, as well as two-way interactions variables between the headline topic and the type of headline. There were no significant interactions with the headline source, so those interaction coefficients were not included in the model. We held the effects of the individual fixed. The two-way interaction between a dummy-coded question headline variable and a dummy-coded variable for the topic of Congress was significant (B = -0.15; SE = -0.06; p < .05). No other two-way interactions were significant. [↩]

- We ran a second fixed effects linear model predicting affective reactions to a news headline. The model included the headline source, topic of the headline, and the type of headline as predictor variables, as well as two-way interactions variables between the headline topic and the type of headline. There were no significant interactions with the headline source, so those interaction coefficients were not included in the model. We held the effects of the individual fixed. The two-way interaction between a dummy-coded question headline variable and a dummy-coded variable for the topic of Congress was significant (B = -0.22; SE = -0.06; p < .05). No other two-way interactions were significant. [↩]

- Bronzan, 2015. [↩]

- We ran a fixed effects linear model predicting affective reactions to a news headline. The model included the headline source, topic of the headline, and the type of headline as predictor variables. We held the effects of the individual fixed. Compared to the traditional nonpartisan headlines (included as the reference group), reactions to the headlines matched with a digital source (B = -0.14; SE = -0.02; p < .05) and headlines matched with an incongruent partisan source (B = -0.21; SE = -0.02; p < .05) were significantly more negative. [↩]

- We ran a fixed effects linear model predicting affective expectations for a news article that would follow the headlines. The model included the headline source, topic of the headline, and the type of headline as predictor variables. We held the effects of the individual fixed. Compared to the traditional nonpartisan headlines (included as the reference group), headlines matched with a digital source (B = -0.14; SE = -0.02; p < .05) and headlines matched with an incongruent partisan source (B = -0.24; SE = -0.02; p < .05) prompted significantly more negative expectations for a news article that would follow the headline. [↩]

- We ran a fixed effects linear model predicting anticipated future engagement with the headline and news story. The model included the headline source, topic of the headline, and the type of headline as predictor variables. We held the effects of the individual fixed. Compared to the traditional nonpartisan headlines (included as the reference group), headlines matched with a digital source (B = 0.13; SE = -0.02; p < .05) significantly increased anticipated future engagement and headlines matched with an incongruent partisan source (B = -0.08 SE = -0.02; p < .05) prompted significantly decreased anticipated future engagement. [↩]

- Notably, this result does not hold for every statistical test. When all individual characteristics of participants are held fixed, a digital news source prompts more anticipated future engagement. When a hierarchical linear model (HLM) is used, instead, with the measured demographic characteristics of the participants (age, sex, race, income, education) included as level-two variables, a traditional news source prompts more anticipated future engagement than a digital news source. [↩]

- Participants were, on average, slightly Democratic (Range: Strong Republican = 1 to Strong Democrat = 4 M = 2.71, SD = 1.022; 15% Strong Republican, 25% Lean Republican, 33% Lean Democratic, 27% Strong Democrat). [↩]

- For a fuller description of a similar experimental design method, see Day, M. V., Fiske, S. T., Downing, E. L., & Trail, T. E. (2014). Shifting liberal and conservative attitudes using moral foundations theory. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 40, 1559–1573. We chose this design because a repeated measures design (where each participant was exposed to headlines of different types but with the same source and/or topic) would have made the purpose of the study too clear for participants. Typically, Latin Square designs are used to control for variables rather than to test for interactions among the variables. However, we increased the sample size to over 2,000 people so that each of the 27 headlines was viewed by a large enough sample to run interaction analyses. Each of the 27 headlines was viewed by between 227 and 241 participants. The large sample size provided enough power to test for two-way interaction effects. [↩]

- We averaged each participant’s responses to these items to create a reactions measure, with higher numbers representing more positive reactions to the headline (Cronbach’s alpha = .84, Range: 1 to 5; M = 3.33, SD = 0.72). [↩]

- We averaged each participant’s responses to these items to create an article expectations measure, with higher numbers representing more positive expectations for the article that would follow the headline (Cronbach’s alpha = .82, Range: 1 to 5; M = 3.32, SD = 0.74). [↩]

- We averaged each participant’s responses to these items to create a future engagement measure, with higher numbers representing a greater anticipation of future news engagement (Cronbach’s alpha = .91, Range: 1 to 5; M = 2.52, SD = 1.04). [↩]