SUMMARY

Previous research by the Center for Media Engagement found that a sense of common humanity – where people recognize that their own failings are common human experiences – can help bring people together. Now we examine whether this feeling can be fostered with something as simple as a meme.

The results of the study show that memes designed to encourage people to think about common humanity helped people feel more positively about people they disagree with politically. This suggests that social media platforms could help bridge divides by prioritizing these types of memes in their algorithms, especially when people are discussing politics.

PROBLEM

Efforts to help ease the animosity that people have for those they disagree with politically have proven particularly elusive.1 This can pose challenges in a democracy because it may limit people’s ability to see issues from others’ viewpoints or to work together to solve problems.2

A recent Center for Media Engagement study found that having a sense of common humanity – where people recognize that their own failings are common human experiences as a means to understand others’ mistakes – might help. We found that the more sense of common humanity people felt, the more likely they were to feel they had the skills to develop relationships with those they disagree with.

The findings led us to examine whether it was possible to foster a sense of common humanity through the use of memes, and, if so, whether it would help people see those they disagree with politically in a better light. This research is part of our connective democracy initiative, funded by the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. Connective democracy seeks to find practical solutions to the problem of divisiveness.

KEY FINDINGS AND IMPLICATIONS

Study findings show that something as simple as a meme can be used to get people in a mindset where they can view their political outgroup more positively. We found that:

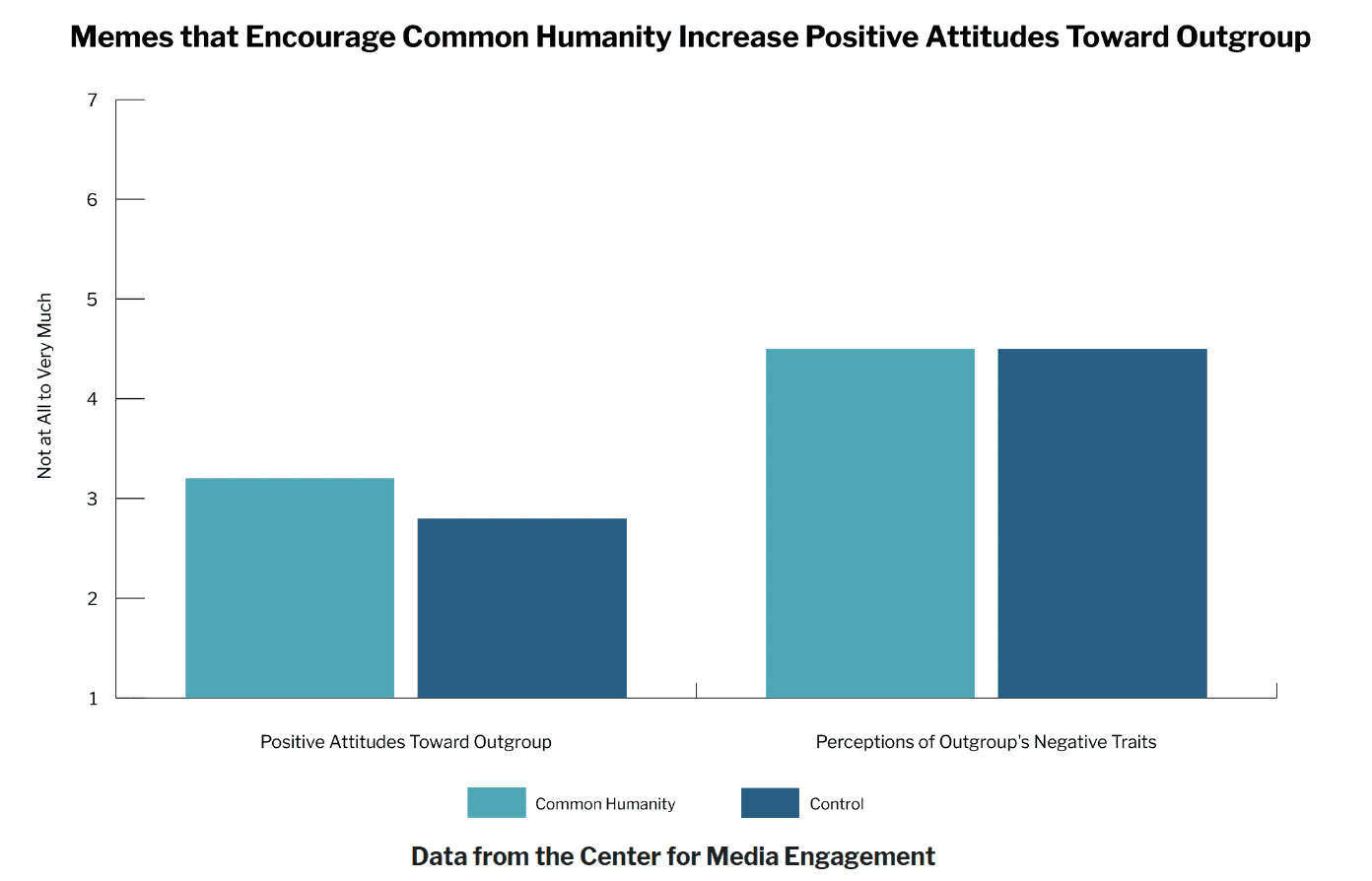

- Using Facebook memes to encourage people to think about their common humanity with others significantly increased their positive feelings toward people they disagree with politically.

- Exposure to the memes had no significant effects on people’s perceptions that people they disagree with politically have negative traits.

This suggests that social media platforms could help bridge divides by prioritizing positive memes in their algorithms, so they would surface to more users. This could be especially effective when people are discussing politics.

FULL FINDINGS

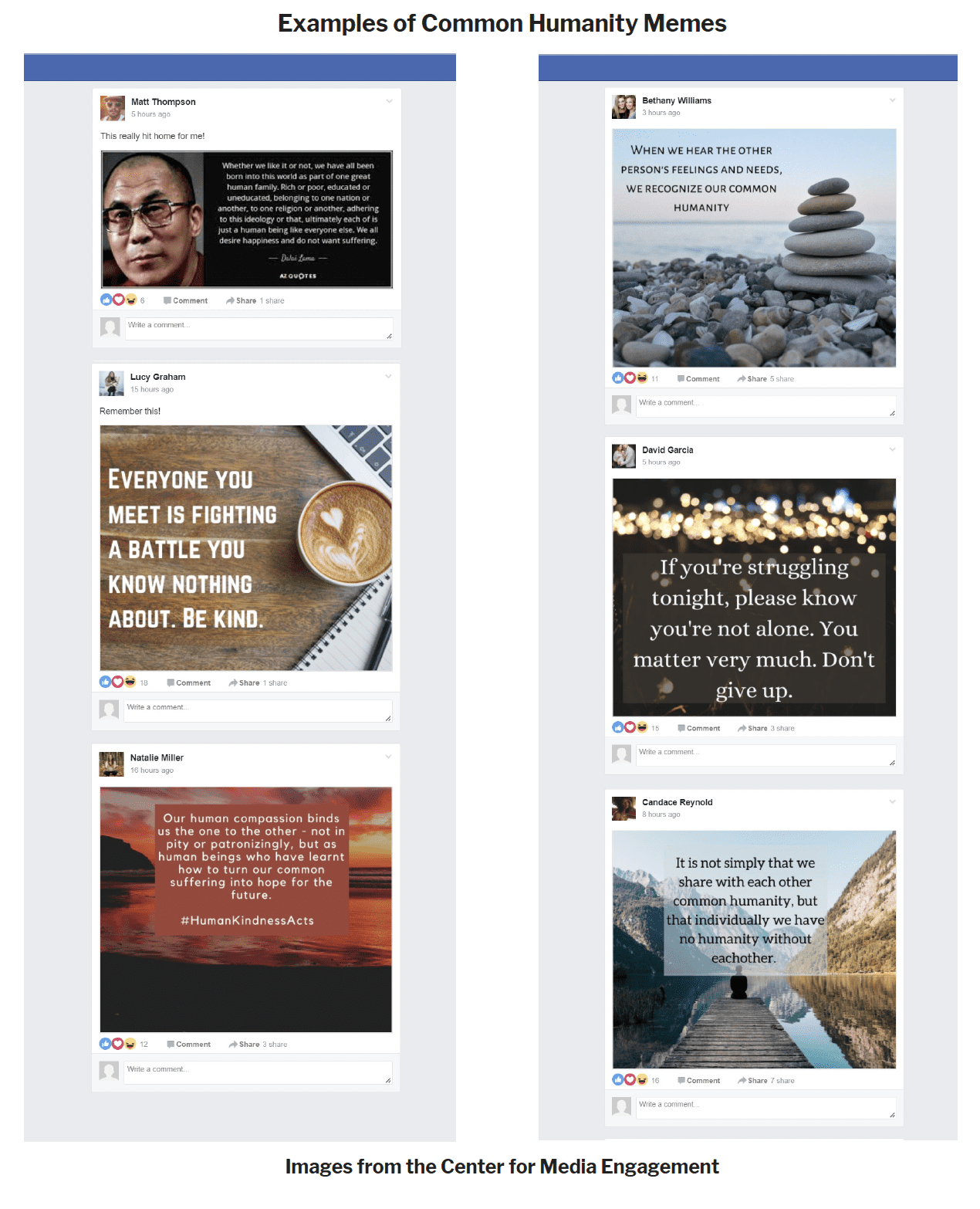

Participants were shown either a Facebook feed with eight memes designed to encourage them to think about common humanity or a control condition that showed a feed with eight generic memes.

Results showed that people exposed to the common humanity memes had significantly more positive attitudes toward their outgroup members,3 although it had no effect on their perceptions that outgroup members have negative traits.4

METHODOLOGY

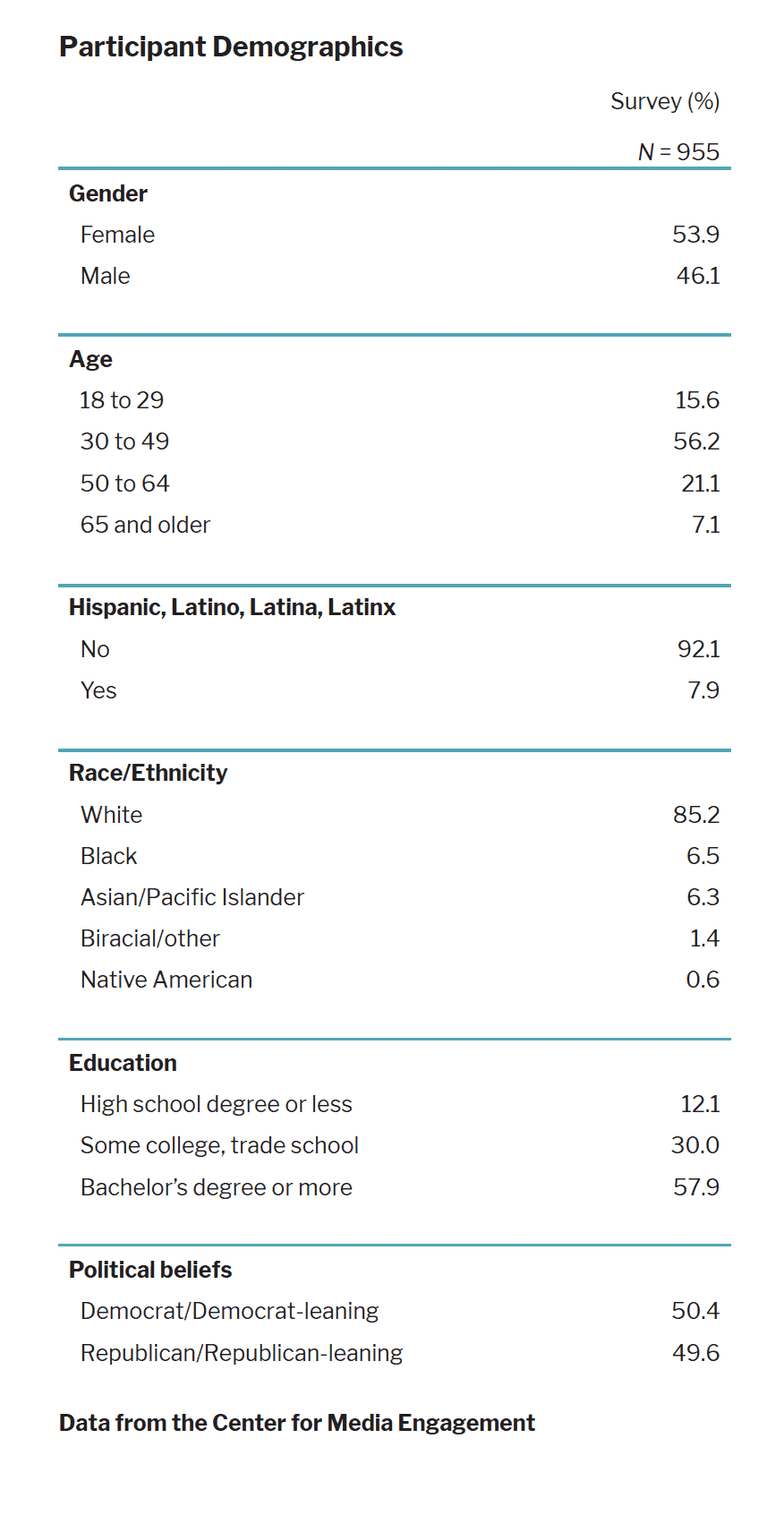

We recruited participants for the experiment through CloudResearch, which draws participants from Amazon Mechanical Turk. Participants had to be at least 18 years old, live in the United States, and follow politics at least some of the time.5 We set up quotas to ensure we would recruit roughly half participants who are Democrats or have Democrat-leaning views and half who are Republican or have Republican-leaning views. This was neither a random nor a representative sample.

After consenting,6 participants (N = 955)7 were randomly assigned to view a thread of Facebook posts that included memes designed to encourage people to think about their common humanity8 with others or a thread of generic memes, which was the control condition. The memes were shown on a functional replica of a Facebook feed and were fully interactive. In both cases, the same generic posts (e.g., “Does anybody have any good book recommendations”) were interspersed within the feed to make it look more realistic.

SUGGESTED CITATION:

Masullo, G. M. (April, 2022). Bridging political divides with Facebook memes. Center for Media Engagement. https://mediaengagement.org/research/bridging-political-divides-with-facebook-memes

- Levendusky, M.S. (2018). Americans, not partisans: Can priming American national identity reduce affective polarization?” The Journal of Politics, 80(1), 59–70; Iyengar, S., Lelkes, Y., Levendusky, M., Malhorta, N., et al. (2019). The origins and consequences of affective polarization in the United States, Annual Review of Political Science, 22(1), 129–146 https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-051117-073034 [↩]

- Hetherington, M. J., & Rudolph, T. J. (2015). Why Washington won’t work: Polarization, political trust, and the governing crisis. University of Chicago Press; Jacobson, G. C. (2016). Polarization, gridlock, and presidential campaign politics in 2016. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 667(1), 226–246. [↩]

- To measure positive attitudes toward the outgroup, participants rated five adjectives regarding people they disagree with politically on a 1 (not at all) to 7 (very much) scale, and these were averaged into an index. These were: “sympathetic,” “soft-hearted,” “warm,” “compassionate,” and “tender,” M = 2.97, SD =1.97, Cronbach’s α = 0.97. This measure was the dependent variable in a one-way ANOVA, F (1, 924) = 15.19, p < .001, η2 = 0.02. Exposure to the common humanity memes significantly increased positive attitudes toward the outgroup (M = 3.2) compared to the control (M = 2.8). [↩]

- To measure perceptions of the outgroup’s negative traits, participants rated 11 adjectives on a 1 (not at all) to 7 (very much) scale, adapted from Wojcieszak, M., & Warner, B. R. (2020). Can interparty contact reduce affective polarization? A systematic test of different forms of intergroup contact. Political Communication, 37(6), 789–811. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2020.1760406. These were: “brainwashed,” “racist,” “hateful,” “misinformed,” “misguided,” “selfish,” “mean,” “reasonable,” “honest,” “caring,” and “informed.” The last four items were reversed scored, so a higher mean was more negative perceptions, and then all were averaged into an index, M = 4.46, SD =1.35, Cronbach’s α = 0.93. This measure was the dependent variable in a one-way ANOVA, F (1, 923) = 0.07, p = .80, η2 = 0.00. Exposure to the common humanity memes had no effect on perceptions of the outgroup’s negative traits (M = 4.5) compared to the control (M = 4.5). [↩]

- This was assessed with the prompt, “Would you say you follow what is going on in government and public affairs …” Those who answered “most of the time” or “some of the time” were permitted to proceed with the experiment, while those who answered “only now and then” or “hardly at all” were not.[↩]

- The Institutional Review Board at The University of Texas at Austin approved the project on March 25, 2021. [↩]

- Initially, 1,187 started the experiment but data were not analyzed for those may have attempted to take the experiment more than once (n = 121), were not interested in politics (n = 51), indicated they could not see the stimuli (n = 26), participated in the experiment more slowly than most participants (n = 16), failed at least one of three attention checks (n = 8), had no Amazon Mechanical Turk ID (n = 6), and did not indicate they identify with either major political party, violating a requirement of the project (n = 4). This resulted in N = 955. [↩]

- The common humanity memes were created by several undergraduate students, based on the concept from Neff, K.D., Tóth-Király, I., Knox, M., Kuchar, A., & Davidson, O. (2021). The development and validation of the state self-compassion scale (long and short form). Mindfulness, 21, 121-140; Neff, K. D., & Pommier, E. (2013). The relationship between self-compassion and other-focused concern among college undergraduates, community adults, and practicing meditators. Self and Identity, 12(2), 160–176. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298868 .2011.649546. Then we pretested these memes to ensure people were perceiving them as fostering common humanity. Across two pretests (n = 65, n = 50), participants were randomly assigned to view either memes meant to depict common humanity or general memes. A series of t tests showed that eight memes intended to depict common humanity were rated as significantly more about common humanity than the generic memes at p < .05. These became the stimuli for the experimental treatment, while the generic memes were the control for the experiment. [↩]