The Center for Media Engagement looked at how uncivil comments affect perception of a news site. We examined two main questions:

- Do uncivil comments on news stories make people perceive other site users and the news site more negatively?

- Do people make this evaluation about the news site based on the first few comments they see or based on the predominant tone of all the visible comments in the stream?

The results of our research showed that uncivil comments do taint perceptions of a news site. We also found that it doesn’t matter if the first comments people see are civil. People’s perception of the site was almost the same whether they saw civil comments or uncivil comments first. This suggests that people make judgments about a news site based on the predominant tone of the comments, not on whether the first comments are civil or uncivil.

The Problem

Online comment sections provide a space for people to give an opinion, learn where others stand, and weigh in on stories that affect their communities. Yet, these sections can also be filled with disrespectful speech marked by profanity, name-calling, and yelling in all caps.1 Previous research has found that uncivil comments made people rate a blog post or a news story more negatively.2 For this project, we looked at whether uncivil comments make people perceive other site users and the entire news site, not just the individual story, more negatively.

Some news organizations urge journalists to post the first comment to set a positive tone for the whole thread.3 This project tested whether this premise actually works to improve audience perceptions of other site users and the news site as a whole.

We examined two main questions:

- Do uncivil comments on news stories make people perceive other site users and the news site more negatively?

- Do people make this evaluation about the news site based on the first few comments they see or based on the predominant tone of all the visible comments in the stream?

To answer these questions, we conducted two online experiments with 520 people in the first experiment and 1,056 in the second.

Key Findings

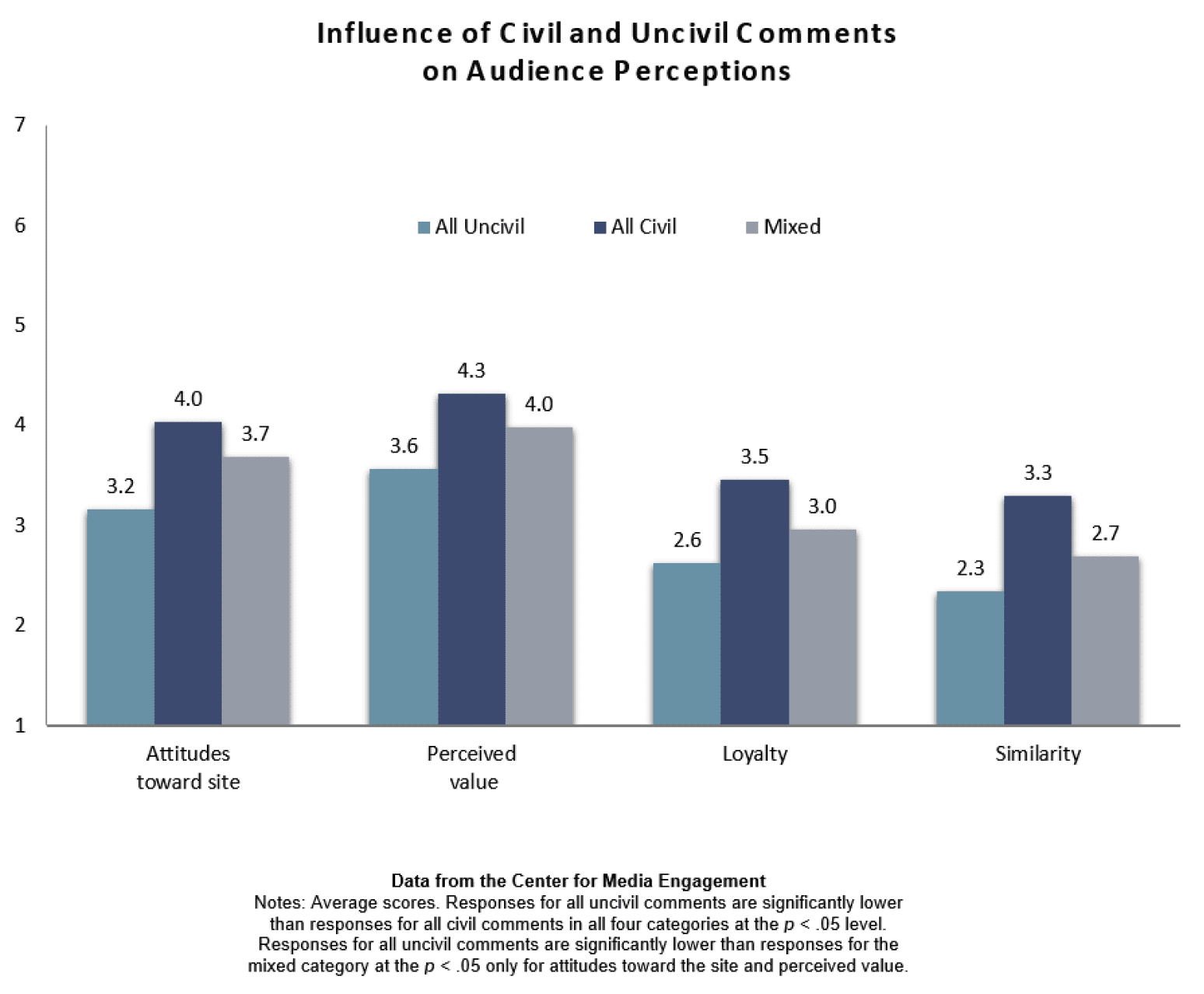

Uncivil comments taint perceptions of a news site

- People who viewed news stories with only uncivil comments had less positive attitudes toward the site and saw it as less valuable, compared to those who saw stories with only civil comments. Those who saw uncivil comments also felt less loyal to the site and less similar to the commenters.

Seeing civil comments first doesn’t matter

- We expected people to view the news site more favorably if the first comments they saw on a story were civil. But we did not find that. In fact, people’s perception of the site was almost the same whether they saw civil comments or uncivil comments first.

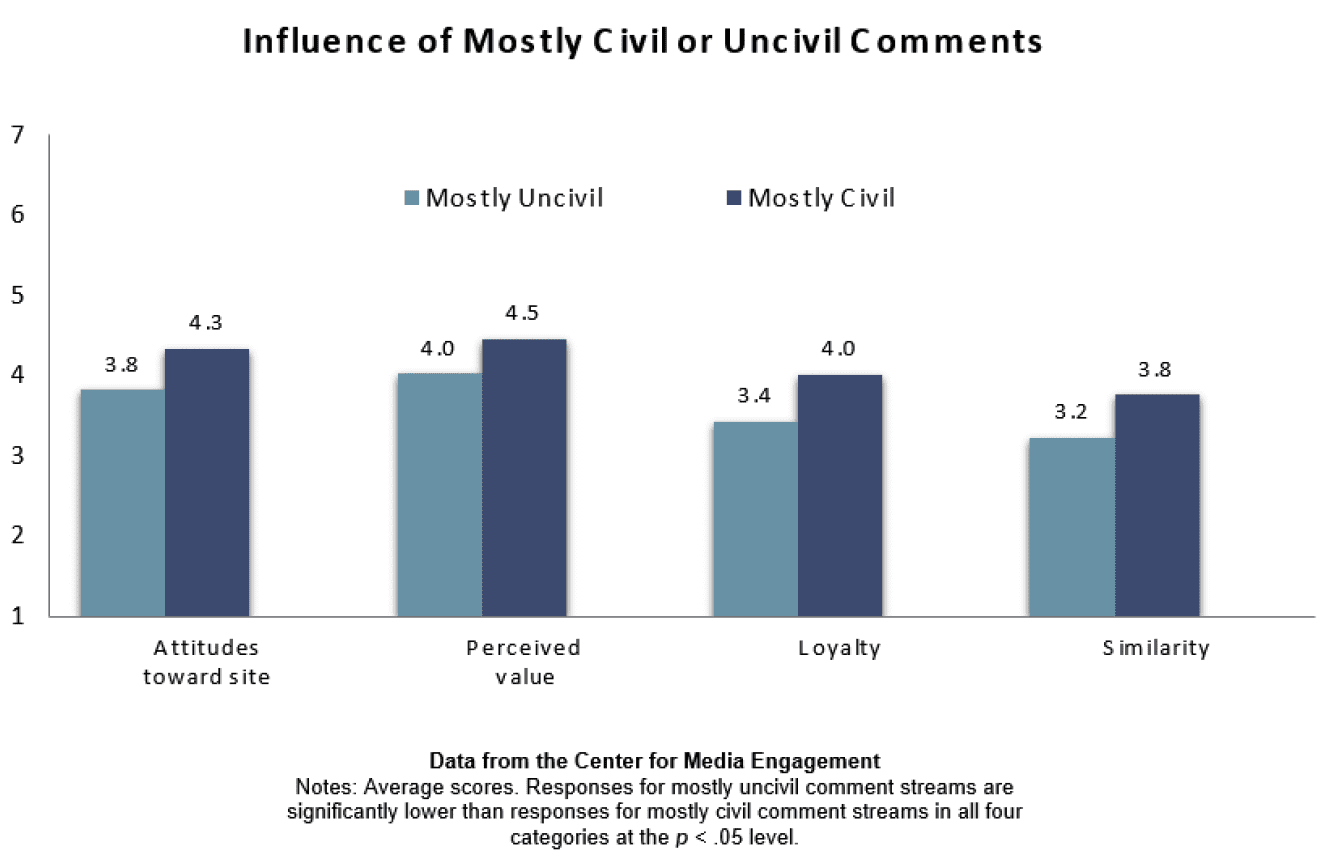

Mostly uncivil comment streams lead to negative perceptions

- People had a more positive view of the news site and other site users if the comment stream they saw contained mainly civil comments. But the order of the comments (civil first or uncivil first) didn’t make much of a difference.

Implications for Newsrooms

Our results suggest that incivility in comment sections can influence how people perceive a news organization’s brand—which is key to attracting an audience.4 The study shows that news organizations would benefit from improving comment sections. Some organizations have tried to deter incivility by encouraging journalists to highlight comments that are civil and thoughtful or to post the first comment to set a positive tone for a comment thread.5 These practices are worthy, but they may not be enough. News organizations should focus on the whole comment stream or at least the parts that are visible when people visit the site.

Our research shows that audience members can handle some incivility when it does not dominate the comment stream. But when 75% of the comments are uncivil, people’s perceptions of the site and the commenting space were less favorable.

In addition, our findings show that setting a positive tone in a comment stream may not be as simple as ensuring that the first few comments are civil. People did not evaluate the news site based on the first few comments, but rather on the overall tone of the visible comment stream. When most comments were civil, they rated the site more highly, even if the comment stream started with incivility.

News organizations that wish to attract and retain an audience should ensure that their comment streams are not overly uncivil. Some news organizations have disabled their comment sections, but we do not recommend this for all newsrooms. Citizen discussions about public affairs can play an important role in a democracy6 and news organizations can help to facilitate these conversations.

The Study

In the first experiment, we showed people news stories with only uncivil comments, only civil comments, or a mix of civil and uncivil comments. We found that news stories with uncivil comments lead people to view a news site and other site users negatively. Specifically, people who saw only uncivil comments on news stories:

- Had less positive attitudes toward the site,7

- Were less likely to perceive the site as valuable,8

- Were less likely to report a sense of loyalty to the news site,9

- Were less likely to feel similar to other commenters on the site.10

Overall Tone of Comment Thread Matters More Than Tone of First Comments

The goal of the second experiment was to figure out whether people made their assessment about the news site and other site users based on the tone of the first few comments they read or based on the predominant tone of the entire thread they viewed. Some people saw news stories that had an even mix of civil and uncivil comments. Others viewed news stories with an uneven mix. There were two types of uneven mix: 75% uncivil and 25% civil, and 75% civil and 25% uncivil.

Our findings show that whether the first few comments were civil or uncivil didn’t matter much. What mattered was the predominant tone of the overall comment stream.

Specifically, we found that when most (75%) of the comments were uncivil, compared to when most of the comments were civil, people:

- Had less positive attitudes toward the news site,11

- Perceived the news site less favorably,12

- Felt less loyalty to the site,13

- Felt less similar to other commenters.14

Methodology

To create comments for the experiments, real comments were collected from news sites. Then comments were tailored so that uncivil comments included markers of incivility – profanity, name-calling, and words in all capital letters to indicate yelling.15 The civil comments also expressed disagreement, but did so without the markers of incivility. For both experiments, the comments were posted on two stories – one about immigration and one about climate change.16 In all cases, half the comments expressed one viewpoint on the topic (such as pro-immigration) and half expressed the opposite stance (such as anti-immigration).17 Before the experiments, 1,146 people who were not involved in the experiments rated the comments for incivility and for whether the comment expressed a view that supported or opposed immigration or supported or opposed the belief that people contribute to climate change.

This report is based on two separate experiments conducted to analyze the effects of comments. They were asked to provide input on the site before it was opened to the general public. Different people participated in each experiment. Both experiments were embedded in surveys and people participated on their own computers.

For the first experiment, we recruited participants through Amazon.com’s Mechanical Turk,18 an opt-in online tool that provides an active self-selected group of participants for small tasks in exchange for payment. They each read two stories that included four comments on each story. Participants were randomly assigned to view comments that were all uncivil, all civil, or a mix of civil and uncivil.

After viewing the stories and comments, participants answered questions about their attitudes toward the news site, how much they valued the site, how loyal they felt to the site, and how similar they felt to the commenters.

For the second experiment, we recruited participants through Research Now SSI,19 an online survey panel, to create a sample more representative of the demographics of the U.S. Internet population.

In the second experiment, the same mock news site and the same news stories were used. However, for this experiment, 16 comments were posted on each story. Each comment thread had a mix of uncivil and civil comments. Participants were randomly assigned to view a comment thread that was either evenly split between civil and uncivil comments or unevenly split (75% versus 25%). They also were randomly assigned to view comment threads that either started with four uncivil comments or four civil comments. As in experiment 1, the comments each person saw were evenly split between expressing a positive view toward the news topic (such as pro-immigration) or a negative view toward the topic (such as anti-immigration).

After viewing the stories and comments, participants answered the same questions as in the first experiment. The questions were about their attitudes toward the news site, how much they valued the site, how loyal they felt to the site, and how similar they felt to the commenters.

SUGGESTED CITATION:

Tenenboim, Ori, Chen, Gina Masullo, and Lu, Shuning. (2019, January). Attacks in the comment sections: what it means for news sites. Center for Media Engagement. https://mediaengagement.org/research/attacks-in-the-comment-sections/

- Coe, K., Kenski, K., Rains, S. A. (2014). Online and uncivil? Patterns and determinants of incivility in website comments. Journal of Communication, 64(4), 658–579. doi: 10.1111/jcom.12104; Chen, G. M. (2017). Online incivility and public debate: Nasty talk. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [↩]

- Anderson, A. A., Brossard, D., Scheufele, D. A., Xenos, M. A., & Ladwig, P. (2014). The “nasty effect:” Online incivility and risk perceptions of emerging technologies. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 19(3), 373–387. doi: 10.1111/jcc4.12009; Anderson, A. A., Yeo, S. K., Brossard, D., Scheufele, D. A., & Xenos, M. A. (2018). Toxic talk: How online incivility can undermine perceptions of media. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 30(1), 156–168. doi: 10.1093/ijpor/edw022; Prochazka, F., Weber, P., & Schweiger, W. (2018). Effects of civility and reasoning in user comments on perceived journalistic quality. Journalism Studies, 19(1), 62–78. doi: 10.1080/1461670X.2016.1161497 [↩]

- Chen, G.M., & Pain, P. (2017). Normalizing online comments. Journalism Practice, 11(7), 876–892. doi: 10.1080/17512786.2016.1205954 [↩]

- See Bogart, L. (1981). Press and public: Who reads what, when, where, and why in America newspapers. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; Meyer, P. (2004). The vanishing newspaper: Saving journalism in the information age. Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press. [↩]

- Muddiman, A., & Stroud, N. J. (2017). News values, cognitive biases, and partisan incivility in comment sections. Journal of Communication, 67(4), 586–609. doi: 10.1111/jcom.12312; Chen & Pain, Normalizing online comments. [↩]

- See Manosevitch, I., & Tenenboim, O. (2017). The multifaceted role of user-generated content: An analytical framework. Digital Journalism, 5(6), 731–752. doi: 10.1080/21670811.2016.1189840 [↩]

- Attitudes toward the site reflected how engaging people found the site and comprised seven statements, such as “I would like to return to this news site again” and “I would like to share content from this site.” People rated their agreement or disagreement on a 7-point scale. This measure is based on a scale used by Chock, T.M., Wolf, J.M., Chen, G.M., Schweisberger, V.N., & Wang, Y. (2013). Social media features attract college students to news websites. Newspaper Research Journal 34(4), 96-108. doi: 10.1177/073953291303400408. [↩]

- For perceived value of the site, participants rated on a 1 (not at all) to 7 (very much) scale how well 10 words, such as “appealing” and “beneficial” applied to the news site. This scale came from Voss, K.E., Spangenberg, R.R., & Grohmann, B. (2003). Measuring the hedonic and utilitarian dimensions of consumer attitudes. Journal of Marketing Research, 40(3), 310–320. doi: 10.1509/jmkr.40.3.310.19238 [↩]

- For loyalty to the site, participants rated their agreement or disagreement on a 7-point scale to five statements, such as “I could feel involved in a news website community like this one” and “I want to be a member of this news site.” These statements came from prior research and were adapted for this project. See Evans, N.J., & Jarvis, P.A. (1986). The group attitude scale: A measure of attraction to group. Small Group Behavior, 17(2), 203–216. doi: 10.1177/104649648601700205. [↩]

- For similarity to other comments, people rated their agreement or disagreement to nine statements, including “Other news website users are like me” and “I am similar to the people who regularly use this news website.” This scale was adapted from previous research. See Chavis, D.M., & Pretty, G.M.H. (1999). Sense of community: Advances in measurement and application. Journal of Community Psychology, 27(6), 635–642. A series of 3 by 2 mixed factorial Analyses of Variances (ANOVAs) was used with tone of debate (uncivil, civil, and mixed) and political beliefs (liberal/Democrat vs. conservative/Republican) as between-subjects factors. Findings showed main effects for attitude toward the site, F (3, 516) = 12.50, p < .001, η2= .05; perceived value of the news site, F (3, 516) = 11.32, p < .001, η2= .04; group loyalty, F (3, 516) = 12.93, p < .001, η2= .05; and sense of similarity to other commenters, F (3, 516) = 19.06, p < .001, η2= .07. [↩]

- These concepts were measured the same way as in experiment one. The effect on attitudes toward the news site was tested using a one-way Analysis of Covariance (ANCOVA) with political beliefs as the covariate. Results showed a significant main effect, F (3, 1053) = 4.45, p = .004 η2 = .01. [↩]

- The effect on perceived value of the news site was tested using a one-way ANCOVA with political beliefs as the covariate. Results showed a significant main effect, F (3, 1053) = 3.40, p = .02 η2 = .01. [↩]

- The effect on loyalty to the news site was tested using a one-way ANCOVA with political beliefs as the covariate. Results showed a significant main effect, F (3, 1053) = 4.29, p = .01 η2 = .01. [↩]

- The effect on sense of similarity to commenters was tested using a one-way Analysis of Covariance (ANCOVA) with political beliefs as the covariate. Results showed a significant main effect, F (3, 1053) = 3.61, p = .01 η2 = .01. [↩]

- Coe et al., Online and uncivil?; Chen, Online incivility and public debate: Nasty talk. [↩]

- These issues were chosen because they were currently in the news and have clear sides likely to foment online debates. See Chen, Online incivility and public debate: Nasty talk; Stroud, N. J., Scacco, J. M., Muddiman, A., & Curry, A. L. (2015). Changing deliberative norms on news organizations’ Facebook sites. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 20(2), 188–203. doi: 10.1111/jcc4.12104 [↩]

- This was done, so that participants would be reacting to the tone (uncivil or civil) of the comments, not the viewpoint toward immigration or climate change expressed in the comment. [↩]

- MTurk has been found to be more representative of the U.S. adult population than student samples, general web samples, or convenience samples. See Paolacci, G., Chandler, J., & Ipeirotis, P. G. (2010). Running experiments on Amazon Mechanical Turk. Judgment and Decision Making, 5(5), 411–419. [↩]

- At the time of the experiments, Research Now SSI was called Survey Sampling International. [↩]