SUMMARY

The Center for Media Engagement looked at people living in areas with limited or no access to local newspapers – so-called “news deserts”– to see how they find news and information and whether they feel informed and are knowledgeable about local issues.

We found that people living in news deserts don’t always believe that they live in news deserts. Those who feel this way said they still have access to information about their community, often through non-traditional sources such as Facebook. Additionally, social cohesion – a sense of trust, belonging, and the willingness to help – correlated with people’s feelings of being informed and their understanding of local issues.

PROBLEM

According to a recent report from the Local News Initiative at Northwestern University, one-fifth of Americans live in a news desert, a community with one or no local newspapers, and thus have limited access to local news.1 This is a problem because the absence of local newspapers is tied to negative democratic outcomes like lower rates of voting and greater polarization and corruption.2 The Center for Media Engagement surveyed people living in news deserts across the U.S. to find out what alternative sources of information allow them to stay informed on local issues. Though some turn to other available news sources like broadcast news and radio, we found that many turn to posts from Facebook pages that share local news.

KEY FINDINGS

People Don’t Necessarily See Themselves As Living in News Deserts

- 46% of those we surveyed who live in news deserts don’t believe their communities are news deserts.

- People who do not believe that their communities are news deserts:

- Believe they can access information about their community,

- Feel more informed about their community, and

- Are more knowledgeable about local issues like community unemployment rates, the presence of superfund sites, and poverty levels than people who agree their community is a news desert.

A Feeling of Social Cohesion is Helpful

- People who view their community as more socially cohesive – meaning people are willing to help their neighbors, feel that others can be trusted, and believe that people get along with each other – are more able to find information, feel more informed, and are more knowledgeable about most local issues than those who view their community as less socially cohesive.

People in News Deserts Still Have Access to News

- Local Facebook pages provide content that meets critical information needs and helps people build community.

- Misinformation is shared in less than 1% of posts from local Facebook pages.

IMPLICATIONS

Local newsrooms could consider experimenting with some of the techniques used on local Facebook pages that serve people in news deserts. For instance, they could employ more audience-centered journalism that reports on specific local people, traditions, or events using the tone of a fellow community member. This sort of journalism may relate to feelings of social cohesion, which our study shows is connected to people’s knowledge and feelings of being informed.

Organizations and individuals producing information for people in news deserts may benefit from training and greater connections to the broader journalism community and to those running similar sources in other communities. The low levels of misinformation in the Facebook pages we analyzed are encouraging, but moving forward, ensuring that these local hubs are well-equipped to deal with challenges like false information is key.

FULL FINDINGS

Many People Living In a News Desert Do Not Believe They Are in One

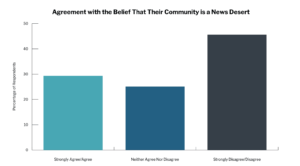

We surveyed 1,007 residents living in zip codes that were categorized as news deserts in previous research.3 When we asked them how much they agreed or disagreed that their “community is a news desert,” 45.6% disagreed or strongly disagreed, even though their community fits the definition of a news desert.4 We note that this was not a random sample, meaning that the actual percentage of people who do not believe that they live in a news desert may differ. Nonetheless, it is noteworthy that a near majority of those who we surveyed did not believe that their area was a news desert.

Note: Ratings are on a scale from 1 (strongly agree) to 5 (strongly disagree).

When asked to explain their rating, many survey participants who agreed that their community is a news desert justified the lack of a newspaper due to factors such as having few people or being rural. “Not a lot happens here” was a typical response.

Those participants who have, or had, access to a local newspaper had concerns. Chief among them was unreliable delivery. One person noted that the local paper is published once per month, so while informative, the news is not current. Another person indicated the same problem from a local paper that closed:

“We had a newspaper, Hopewell News. It closed down about 6 years ago. It was [a] twice a week publication. Now, we have the Progress-Index that covers some of our local news, such as festivals or accidents. We don’t have news about everyday, down to earth stuff. We had 4 prisoners escape from the prison which is run by our county. We didn’t know about it until they were still looking for 2 [of] them!”

Those who indicated that their community is not a news desert said that they received information about their community through local television, newspapers, and radio. One participant summed up the availability of information:

“We live in a pretty decent sized city. There is a lot of places to access the news. Mainly being that we’re in 2022, most people have access to phones and social media. In today’s society, you can’t get on social media without seeing what’s happening in the news locally and around the country/world.”

Others who disagreed that their community is a news desert mentioned access to non-traditional sources for news as a rationale. These responses included mentions of local Facebook pages, Chambers of Commerce, community bulletin boards, and word of mouth. One participant even noted the importance of physical billboards:

“Because there is info online and our newspaper comes out once a week. There is also info on [an] electronic billboard by the library. This is a small town, but we can find out what we need to know easily.”

People Who Believe They Don’t Live In News Deserts Feel Informed

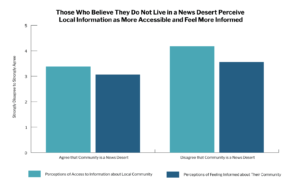

Next, we asked participants about their perceptions of access to information about their local community, perceptions of being informed on local issues, and their knowledge about their local community.

Compared to those who believed that they did live in a news desert, participants who did not believe their community is a news desert were more likely to report that they:

- Have access to information about local politics

- Know where to get information about community events

- Believe it is easy to find news about local issues

- Feel informed about what is happening in their community

- Are up to date with local issues

- Are familiar with what elected officials are working on

Notes: Average ratings are shown. Survey participants rated how much they agreed with a series of questions about their access to information about their local community and feelings of being informed on a 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) scale. Means were significantly different at p < .001.5

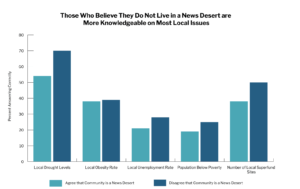

People Who Feel They Don’t Live In News Deserts Are Knowledgeable About Local Issues

We wanted to know how knowledgeable people actually were about their local communities. We asked the survey respondents a series of multiple choice questions about the number of weeks their county was in a severe drought in the previous year, the percentage of the adult population that is considered obese in their county, the unemployment rate in their county, the percentage of their county’s population below the poverty level, and the number of superfund sites located in their county. We recorded whether their responses were correct or not.

On average, people who disagree that their community is a news desert were more knowledgeable on 4 of the 5 issues. Obesity was the only local issue where we found no differences between those who agreed their community was a news desert and those who disagreed.

Notes: Percentages are shown. Survey participants answered each knowledge question by selecting among multiple choice response options. Their responses were coded as correct or incorrect. Means were significantly different at p < .001 for the drought and superfund questions. Means were significantly different at p < .05 for the unemployment and poverty questions. Means did not differ significantly for the obesity question.6

People Who Feel Their Community Is Socially Cohesive Feel More Informed

We asked participants about the people in their communities and whether they felt that their communities are socially cohesive, meaning people are willing to help their neighbors, can be trusted, and get along with each other. We found that the more people believe their community is socially cohesive, the more likely they were to:

- Feel informed

- Believe they can find local information

- Actually be more informed about local issues (drought frequency, unemployment rates, populations in poverty, number of superfund sites)7

Many People in News Deserts Get Local News from Social Media

In our survey, 35.9% of respondents reported getting information about their local community from social media “every day.” Social media represented the most frequently accessed source for local information among the sources that we asked participants about (local newspaper, local television, local radio, blogs, newsletter/email, word of mouth, post office or local bulletin boards, and church or religious organizations).

We wanted to know what type of local, public Facebook content people in news deserts consume. To do this, we examined 3,010 Facebook posts shared by local pages. We came up with a list of sources by contacting librarians or town officials in 87% of all U.S. counties without a local newspaper8 and asking them where people in their communities go for news. We supplemented their list with our own keyword searches through Facebook, a technique similar to one that might be employed by residents of these localities.

Local Facebook Pages Share Mostly Local, Mostly Informative News

Of the 3,010 posts that we examined, 87.7% were locally focused. The remaining 12.3% of posts communicated state- or national-level information. In our analyses below, we focus only on those posts that were locally focused.

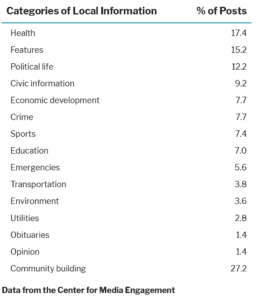

Posts could be categorized into more than one category of local information. The most popular categories of news featured in the posts were health9 (17.4%), features or human interest posts (15.2%), political life (12.2%), civic information (9.2%), economic development (7.7%), and crime (7.7%).

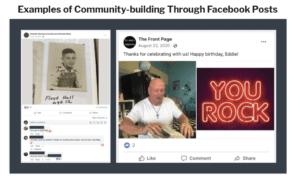

Community-building posts (27.2%) included notices of community events, historical information or photos from the community, general local announcements, lost/found items or pets, birthday/anniversary/wedding announcements and wishes, and instructional or how-to posts. We include examples of these types of posts below.

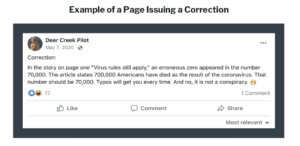

Misinformation Is Rarely Shared By Local Public Facebook Pages

Of the posts that shared local information, we found almost no misinformation.

- Only 8 posts (0.3% of our sample) addressed the issue of misinformation or shared false content.

- Of these posts, two were corrections to previous posts by the Facebook pages themselves. Two posts were flagged and fact-checked by Facebook and an additional two posts addressed the ongoing nature of a story and the need to wait to share information. One post refuted a local rumor, and one post was a piece of misinformation about hydroxychloroquine and ivermectin that went unchecked.

Even of the posts that shared non-local information, we found only two posts that addressed the issue of misinformation. One was a shared video produced by PolitiFact about fact-checking voter fraud misinformation. The other was a meme featuring misinformation about COVID-19 and patent claims.

Local Facebook Pages Vary In Who Shares News and How

We also considered how content from local Facebook pages is shared. We found that:

- Of local posts, 18.4% were shared from other sources, such as local school districts, sheriff’s departments, utility providers, or Chambers of Commerce.

- Posts infrequently ask people to engage, such as requests to share content or like the page (2.6%).

- Some posts include calls-to-action (18.7%), such as encouraging readers to:

- Read a full news article on another site

- Abide by emergency safety protocols such as avoiding the site of an accident or following shelter-in-place orders

- Participate in civic behaviors like mask-wearing or voting

- Attend community events

The sources of local Facebook pages are sometimes not traditional sources of news, though as noted above, do share information critical to local communities. Additionally, these pages do more than communicate local news as they engage less in self-promotional posting and more in calls-to-action that encourage fellow community members to take actions that benefit society.

METHOD

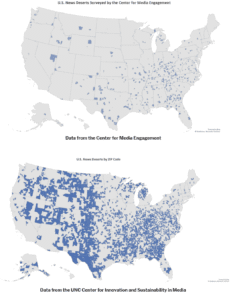

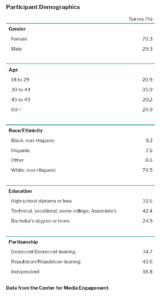

The findings that we report are based on survey responses from 1,007 residents of local news deserts (with one or no local newspaper) as well as from an analysis of 3,010 posts from 301 public Facebook pages in news deserts with no local newspaper. We combine these data to understand the quality of information, perceptions about the availability of information, feelings of being informed, and actual knowledge about local communities.

Measuring Audience Perceptions

We contracted with SSRS to survey 1,007 residents who lived in one of 4,806 ZIP codes that have been identified as news deserts by the Local News Initiative at Northwestern University. We balanced our survey of people living in counties identified as news deserts based on whether their county had no local newspapers (n = 505) or a single local newspaper (n = 502). The study was fielded in both English and Spanish in June of 2022. In total, 1,000 participants took the survey in English and seven participants took the survey in Spanish.

Below are maps of (1) the news deserts represented among our survey respondents along with (2) all news deserts in the U.S. from which we sampled.

Assessing Facebook Pages in News Deserts

To assemble the list of 301 public Facebook pages, we (a) searched on Facebook and (b) contacted librarians or town officials in U.S. counties identified as news deserts.

We assembled a list of Facebook pages and groups identified by searching for town and county names via Facebook. For example, we would search “Fluvanna Virginia news” or “Palmyra Virginia news” to uncover pages and groups that might serve Fluvanna County, Virginia of which Palmyra is one of the larger towns. Using these methods, we identified 253 Facebook pages. Of these pages, 233 were public and 20 were private.

To ensure that our means of locating local pages was exhaustive, we contacted people in 148 of the 171 counties across the U.S. without local newspapers as identified by Abernathy (2020).10 We were unable to contact someone in the remaining 23 counties. Of the 148 counties that we contacted, there were 33 counties where we either could not locate a local library or could not reach a librarian at the library. In these instances, we contacted the mayor’s office of the largest town in the county. In total, we received emails from 62 librarians and spoke to 53 of them by phone. We randomly selected 10% of the counties in our population of news deserts and contacted all of the towns within those counties to be sure that our methods surfaced all possible information-sharing Facebook pages. We did not find that this method yielded more results than contacting the largest town in each county and proceeded with our initial method.

In our conversations, we mentioned to the librarians or town officials that their county was considered a news desert, which was often met with disagreement and further detail about the local information environment. Their explanations are illustrative. For example, a librarian in Denali Borough, AK, told us that Fairbanks was the nearest town, around 110 miles to the north, so a local newspaper wasn’t needed because their news was shared on a local Facebook page, through local prayer chains, or by word of mouth. Similarly, a county clerk in Macon County, GA, noted that a retired journalist in the community publishes an online newspaper. In Rich County, UT, home delivery of mail does not exist; all residents must go to their local post office to retrieve mail. Consequently, they receive considerable local news and information about their community through physical bulletin boards. These conversations started as a method to identify local Facebook pages or groups that shared local news, and potentially problematic content, in news deserts. The conversations ended with a rethinking of what constitutes “news deserts” and a desire to re-evaluate the lens through which we view different, but possibly still rich, information environments.

Overall, this method of contacting librarians and elected officials allowed us to identify an additional 133 Facebook pages or groups. Of these, 105 were public and 29 were private. Notably, many of the pages identified through this method either duplicated those in our original list or consisted of pages operated by official governing bodies such as the local Sheriff’s Department, Chamber of Commerce, or school district. Although these are not pages that we originally would have considered news, we include them in our dataset.

Using both methods, we identified a total of 386 local news Facebook pages or Groups. We excluded pages that were private (n = 49), or which had not shared more than 20 posts in our 20-month sampling period (January 1, 2020, to September 30, 2021) as we considered these to be inactive pages (n = 36). Excluding these pages left us with a final sample of 301 local news Facebook pages.

To analyze the content of these pages, we collected posts using data from CrowdTangle, a public insights tool owned and operated by Meta.11 Since CrowdTangle only accesses public pages, we excluded private pages or groups from our dataset. We pulled all of the posts from January 1, 2020, to September 30, 2021. This time frame represents the start and continuation of the COVID-19 pandemic, which is a period where sharing explicitly local news about COVID infections, restrictions, and deaths would be of the utmost importance to communities. If these pages were to traffic heavily in local news addressing critical information needs, this is a time frame when we would most expect to see that type of content. We randomly sampled 10 posts from each page to produce a final dataset of 3,010 posts. This method ensured that we did not oversample from pages that were particularly prolific. Next, we coded each post for whether it (1) was local/not local, (2) addressed critical information needs such as emergencies, health, and economic development, (3) contained misinformation, or (4) was meant to encourage engagement with the page rather than to communicate news and information.12

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Natalie (Talia) Jomini Stroud and Gina M. Masullo for their contributions to the survey and for providing extensive feedback on previous versions of this paper. Thank you also to Julia Elias and Abby Nguyen for their assistance with the survey. This report was supported with funding from Democracy Fund and the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation.

Suggested Citation

Collier, J. R. & Graham, E. (December, 2022). Even in “news deserts” people still get news. Center for Media Engagement. https://mediaengagement.org/research/people-still-get-news-in-news-deserts

- Abernathy, P. M. & Franklin, T. (2022, Oct. 4). The state of local news 2022. Local News Initiative, Medill School of Journalism, Media, Integrated Marketing Communication, Northwestern University.[↩]

- Darr, J. P., Hitt, M. P., & Dunaway, J. L. (2018). Newspaper closures polarize voting behavior. Journal of Communication, 68(6), 1007-1028; Darr, J. P., Hitt, M. P., & Dunaway, J. L. (2021). Home style opinion: How local newspapers can slow polarization. Cambridge University Press; Rubado, M. E., & Jennings, J. T. (2020). Political consequences of the endangered local watchdog: Newspaper decline and mayoral elections in the United States. Urban Affairs Review, 56(5), 1327-1356; Shaker, L. (2014). Dead newspapers and citizens’ civic engagement. Political Communication, 31(1), 131-148.[↩]

- Abernathy, P. (2020). News deserts and ghost newspapers: Will local news survive? The Center for Innovation and Sustainability in Local Media, Hussman School of Journalism and Media. https://www.usnewsdeserts.com/[↩]

- To measure perceptions that their community is/is not a news desert, participants were first provided the following lay definition of news desert: “A news desert is a community where residents have very limited access to news and information about local issues and local politics.” Then, they were asked to indicate on a scale from 1 (strongly agree) to 5 (strongly disagree) their level of agreement with the statement: “My community is a news desert.” 25.1% neither agreed nor disagreed, 19.1% agreed, 10.2% strongly agreed, 28.3% disagreed, and 17.3% strongly disagreed.[↩]

- Access to information was measured using three items: “I have access to information about local politics,” “When something happens in my community, I know where to go for information,” and “It is easy for me to find news about local issues.” Participants rated their agreement with each statement from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Items were averaged together to create a measure of access to information, Cronbach’s ɑ = 0.87. Feelings of being informed were measured using three items: “I feel informed about what is happening in my community,” “I am up to date with local issues,” and “I am familiar with what elected officials are working on.” Participants rated their agreement with each statement from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Items were averaged together to create a measure of feeling of being informed, Cronbach’s ɑ = 0.86. All findings were tested using ANOVAs. The measure of whether participants believed their community is a news desert was collapsed into a binary measure of (a) participants believed their community is not a news desert and (b) participants who believed that their community is a news desert or neither agreed nor disagreed with description. In each ANOVA, perceptions that their community is/is not a news desert was entered as a between-subjects factor. For access to information, there was a significant main effect of perceptions that community is/is not a news desert, F(1,1000) = 171.1, p < .001. For feelings of being informed, a significant main effect was also found for perceptions that community is/is not a news desert, F(1,977) = 56.39, p < .001.[↩]

- All findings were tested using ANOVAs. In each analysis, perceptions that their community is/is not a news desert was entered as a between-subjects factor. For drought, a significant main effect was found for perceptions that community is/is not a news desert, F(1,1005) = 27.17, p < .001. For unemployment, a significant main effect was found for perceptions that community is/is not a news desert, F(1,1005) = 14.67, p < .001. For poverty, a significant main effect was found for perceptions that community is/is not a news desert, F(1,1005) = 5.45, p < .05. For superfund sites, a significant main effect was found for perceptions that community is/is not a news desert, F(1,1005) = 4.77, p < .05 . For obesity, no significant effect of news desert perceptions was found, F(1,1005) = 0.21, p = .648.[↩]

- These are the results of several OLS regressions. In each analysis, social cohesion was entered as an independent variable. For feelings of being informed, greater social cohesion was associated with significantly greater feelings of being informed (B = 0.34, SE = 0.04, p < .001). For access to information, greater social cohesion was associated with significantly greater access to information (B = 0.38, SE = 0.04, p < .001). These analyses were repeated for knowledge of local issues. For drought, greater social cohesion was associated with significantly greater knowledge of local drought levels (B = 0.07, SE = 0.02, p < .001), local unemployment rates (B = 0.07, SE = 0.02, p < .001), local population in poverty (B = 0.04, SE = 0.02, p < .05), and superfund sites (B = 0.10, SE = 0.02, p < .001). Again, for the issue of obesity, we find no significant result. Social cohesion is not significantly associated with knowledge of local obesity rates, (B = 0.01, SE = 0.02, p = .510)[↩]

- We were unable to contact individuals in 23 U.S. counties identified as news deserts without a local newspaper.[↩]

- The posts in our dataset were shared between January 1, 2020, and September 30, 2021. This timeframe represents the start and continuation of the COVID-19 pandemic, which may be one reason why we see a high prevalence of health-related news.[↩]

- Abernathy, P. (2020). News deserts and ghost newspapers: Will local news survive? The Center for Innovation and Sustainability in Local Media, Hussman School of Journalism and Media. https://www.usnewsdeserts.com/[↩]

- CrowdTangle Team (2022). CrowdTangle. Facebook, Menlo Park, California, United States. [1543057][↩]

- Two independent coders coded a sample of the full dataset of posts. Disagreements were discussed through several rounds of coding to achieve reliability for each of the coding categories.[↩]