SUMMARY

American society today feels more divided than ever, particularly along racial lines. In this project, the Center for Media Engagement asked Black Americans how news organizations could better cover their communities to help bridge the divide between them and the media. We found that:

- Journalists Aren’t Trusted Storytellers: Overall, our survey showed that Black Americans’ trust in news is low, similar to most Americans’ trust in news. Our interviews showed that Black Americans did trust journalists in general, but they did not necessarily trust journalists to cover Black communities.

- Journalists Aren’t Well Known in Black Communities: Most participants had never met a journalist in their communities. They didn’t know how to connect with journalists.

- Coverage Isn’t Complete: Participants felt coverage of their communities lacked context and was one-sided and incomplete.

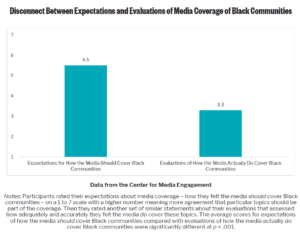

- Expectations Don’t Match Reality: There was a stark disconnect between how Black Americans felt the media should cover their communities and how they felt the media actually do cover their communities.

- Coverage and Representation Matter: What really influenced whether Black Americans trust the news media was how well they felt the media covered their communities, and, to a lesser extent, how diverse they felt newsrooms were. Being a Democrat or liberal-leaning and older also were linked to greater media trust.

Our interviews helped reveal six approaches journalists can take to help bridge the divide between the media and Black communities.

THE PROBLEM

News coverage of the death of George Floyd at the hands of police in the summer of 2020 – and the resulting protests – highlighted a decades-long problem with how Black Americans are covered in the media.1 Floyd, a Black man, died after a white Minneapolis police officer kneeled on his neck, pinning Floyd to the ground for nearly nine minutes.2 His death was just one of hundreds of deaths of Black Americans caused by police in recent years.3 The cases have raised concerns about police violence,4 the justice system, racism, and how the media responds to this crisis.5

Headlines and front pages covering Floyd’s case and others like it have been critiqued for their emphasis on sensationalism over substance and their focus on property damage during protests, rather than on larger issues like racism in everyday life. Coverage of Floyd’s case led to several walkouts from journalists claiming they were “sick and tired of pretending things are ok.” Critiques of the media coverage of Black Americans are not new. More than 50 years ago, the Kerner Commission warned against divisive news coverage that did not accurately or adequately represent Black people6 and called for more diverse newsrooms. But these problems remain.7

In this project, the Center for Media Engagement asked Black Americans how news organizations could better cover their communities to help bridge the divide between them and the media. This research, funded by the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation and Democracy Fund, is part of our connective democracy initiative. Connective democracy seeks to find practical solutions to problems of divisiveness.

KEY FINDINGS

The following findings stand out:

- Journalists Aren’t Trusted Storytellers: Overall, our survey showed that Black Americans’ trust in news is low, similar to most Americans’ trust in news. Our interviews showed that Black Americans did trust journalists in general, but they did not necessarily trust journalists to cover Black communities.

- Journalists Aren’t Well Known in Black Communities: Most participants had never met a journalist in their communities. They didn’t know how to connect with journalists.

- Coverage Isn’t Complete: Participants felt coverage of their communities lacked context and was one-sided and incomplete.

- Expectations Don’t Match Reality: There was a stark disconnect between how Black Americans felt the media should cover their communities and how they felt the media actually do cover their communities.

- Coverage and Representation Matter: What really influenced whether Black Americans trust the news media was how well they felt the media covered their communities, and, to a lesser extent, how diverse they felt newsrooms were. Being a Democrat or liberal-leaning and older also were linked to greater media trust.

IMPLICATIONS FOR NEWSROOMS

Our interviews helped reveal the following six approaches journalists can take to help bridge the divide between the media and Black communities:

- Find “Black Joy”: Intentionally cover positive stories about Black people and communities, rather than focusing coverage on police brutality or protests.

- Provide a More Complete Story: Develop more sources in Black communities and tell stories that include their points of view, rather than overly rely on official government sources.

- Diversify Blackness: Don’t treat one neighborhood or community as “Black people.” Instead, realize that Black people live throughout your coverage area and that their needs and beliefs are not all the same.

- Explore Your Own Unconscious Biases: Think about the decisions you make about what stories to cover and how you cover those stories, even if it makes you uncomfortable.

- Hire Black Journalists: Make a real commitment to hiring diverse staff at all levels.

- Connect with Black Communities: Build trust by finding ways to make connections in Black communities before big news happens. Consider getting involved in local causes or community events.

FULL FINDINGS

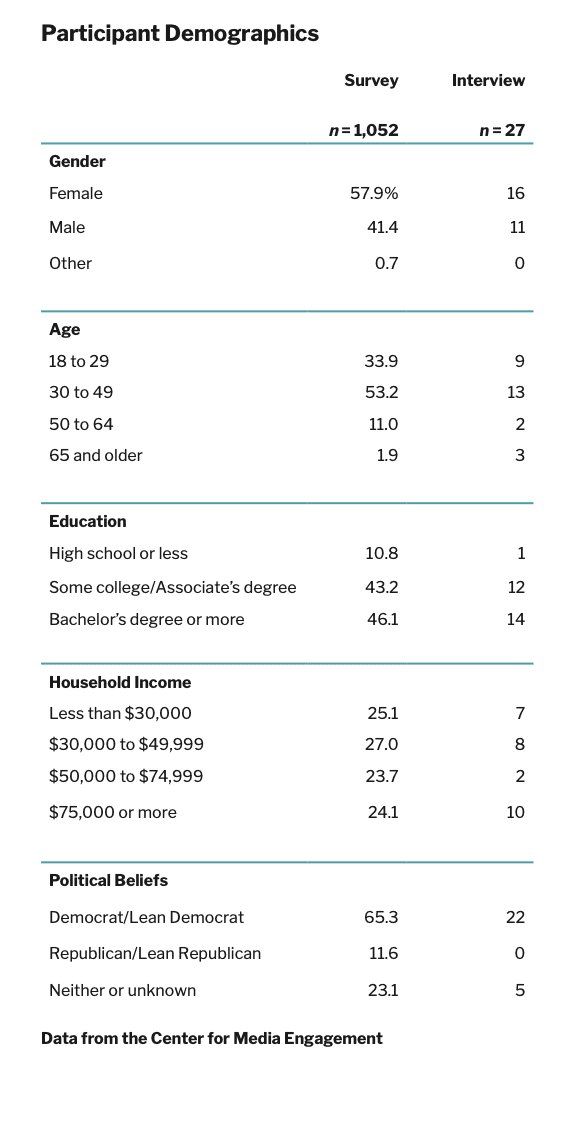

We surveyed 1,052 Black Americans and then interviewed 27 of them at length. Participants are described using their chosen pseudonym. Our findings focus on two main areas: “What’s Wrong?” and “How Do We Fix It?”

What’s Wrong?

Across the survey and interviews, Black Americans identified the following four main issues regarding their perceptions of the news media.

Journalists Aren’t Trusted Storytellers

In the survey, Black Americans rated low trust in media, with an average score of 3.2 on a 1 to 7 scale with 7 indicating higher trust.8 When they were asked to answer an open-ended question about media trust, their answers were related to media bias or biased news 467 times. The interviews provided more nuance about this finding. Participants seemed to trust journalists in general, but that trust was weaker when it came to covering Black communities. “For the local news, I kind of trust them. … [But] they’re so quick to post negative stories about minorities,” said Sarah, 36, of Louisiana.

Others noted they thought bias might be intentional. For example, Palla, 34, of Pennsylvania, said: “There’s some journalists in particular who have their own agenda, and they don’t, they’re not as impartial as they should be. … I think, you know, there’s certain people out there that I think are getting some kind of financial benefit from how they report, and that just disgusts me.”

Journalists Aren’t Well Known in Black Communities

Most participants had never met a journalist in their communities and didn’t know any journalists who work in their communities. They also didn’t know how to connect with journalists or understand how journalists specifically reach out to and connect with communities. People also felt that local newsrooms lacked diversity.

Coverage Isn’t Complete

Many participants felt coverage of their communities lacked context and was one-sided and incomplete. For example, they perceived that news coverage presented Black Lives Matter protests as overwhelmingly violent even though the protests were largely peaceful.9 “They have been showing protestors as overly violent, when in actuality, it’s the police that’s actually starting to [aggravate] issues between them,” said Kole, 18, of Georgia.

Expectations Don’t Match Reality

In survey responses, Black Americans indicated a strong preference for the media taking on the role of helping the public understand racial injustice and breaking down barriers between people, as well as covering protests like Black Lives Matter. But they did not see the media as actually doing a very good job of this. There was a stark disconnect between Black Americans’ expectations – how they felt the media should cover their communities – compared with their evaluations – how they believed the media actually does cover their communities.10

How Do We Fix It?

Coverage and Representation Matter

To understand more fully what might improve Black Americans’ trust in news, we examined what attitudes made it more likely that people would trust the media. In the survey, we considered “expectations of how the media should cover Black communities,” “evaluations of how the media actually does cover Black communities,” “perceptions of newsroom diversity,”11 and “general perceptions of the treatment of Black people in American society.”12 Statistical analyses showed the following results from the survey:

- The more people perceived that the media did a good job of covering Black communities and the more they perceived that newsrooms are diverse, the more likely they were to trust the media. Coverage perceptions mattered more than perceptions that newsrooms are diverse.13

- Participants who identify as Democrats or liberal-leaning or who are older also were more likely the trust the media.

- “General perceptions of the treatment of Black people in American society” and “how the media should cover Black communities” were not related to media trust perceptions.

Strategies for Journalists

In the interviews, our participants offered six main strategies that news outlets could take to bridge divides with Black Americans, as described below.

Find “Black Joy”

Participants suggested intentionally covering positive stories about Black people and communities, not focusing coverage on police brutality or protests. “I’d like to see like a counter-balance of ‘Here’s a really positive thing that’s happening in the community,’ or like, ‘Here’s a way that you can help today.’ I don’t know, just a balance in between the awful and the kind of more upbeat,” explained Lucy, 21, of California.

Provide a More Complete Story

Participants yearned for journalists to develop more sources in Black communities and to tell stories that include these voices even if they conflict with what police or other officials are saying. All too often, participants felt they weren’t getting the whole story. “I really think that [media] contribute to racism when they won’t tell the whole story, you know? If I was to see Black Lives Matter anything concerning them … the media gives me 90% of them knocking in the windows and things of that nature. … I always feel like I’m missing the rest of the story,” said Abigail, 52, of New York.

Diversify Blackness

Participants wanted journalists to realize that Black people live throughout a community, not just in specific neighborhoods, and that they have varied experiences and beliefs. It’s also important for journalists to report on variations within Black thinking about solutions to problems and to push against seeing Black people as all the same by allowing various Black voices in news coverage. “I guess for me personally, it’s being aware that we’re not all the same. … We’re just as diverse economically and socially as every other group in the country,” said Mark, 31, of Florida.

They also wanted journalists to understand that Black people fall into intersecting social groups, based on income, education, geographic location, etc., that may make their experiences different from each other. Journalists should take that into account when diversifying coverage to make it more relatable. Explaining this point, Croft, 25, of Missouri said, “Rural, poor people and black people actually have a lot in common, but the media likes to act like they just have completely separate problems that aren’t related.”

Explore Your Own Unconscious Biases

Participants recommended that reporters and editors think about their own unconscious biases by exploring ideas or questions that might make them uncomfortable as they consider what stories to cover and how to cover them. Then journalists should include those narratives in their coverage. Queen, 60, of New York, said that one way journalists can combat racism is by “making decent white people feel uncomfortable. That’s the thing that’s going to spark some kind of debate and possible change.”

Hire Black Reporters

With calls for the diversification of newsrooms beginning as early as the 1960s, this solution is not new or unique. However, studies show newsrooms are still dominated by white men, particularly in management, so more work is needed.14 Participants said this lack of diversity needs to change. “Hire more black reporters, writers, and management from top to bottom level,” said Quincy, 26, of California.

Connect with Black Communities

Most participants didn’t know journalists in their communities or know how to go about contacting a reporter. To address this concern, journalists could get more involved in local causes or community events that may help connect them to Black communities. “I think the easiest way [journalists can bridge racial divides] is to just spend more time or be more comfortable around other minority groups,” said Mark, 31, of Florida. “I know for a fact I wouldn’t be nearly as comfortable around white people if I didn’t spend my whole life being around them.”

METHODOLOGY

This project was funded by Knight Foundation and Democracy Fund as part of the connective democracy project. We recruited 1,05215 participants through CloudResearch, which draws participants from Amazon Mechanical Turk. Participants had to identify as Black Americans,16 be at least 18 years old, and reside in the United States. This is neither a representative nor a randomly selected sample, but we specifically sought out a cross-section of Black Americans.

Participants were asked open-ended and close-ended questions about their general impressions of what it’s like to be a Black American, their media and news use, and their perceptions of how the news media covers Black Americans. All participants were invited to be interviewed, and 531 indicated a willingness to do so. Participants who agreed to be interviewed were randomly selected to be invited to interviews, although efforts were made to balance gender, income, and education categories in those invitations. A total of 257 were invited to be interviewed, and of those, 27 went through with the interview process. The survey and interviews took place from August 1 to 31, 2020.

Interviews were conducted via Zoom and each lasted about 45 minutes. They were recorded and professionally transcribed. During interviews, participants elaborated on their perceptions of life as Black Americans and media coverage of Black communities. We looked for commonalities in their observations. A computer program was used to help sort through interview transcripts to aid in analysis.

- Campbell, C., LeDuff, K., Jenkins, C. D., & Brown, R. A. (2012). Race and news: Critical perspectives. Routledge. [↩]

- Montemayor, S., & Xiong, C. (2020, June 4). Four fired Minneapolis police officers charged, booked in killing of George Floyd. Star Tribune. https://www.startribune.com/four-fired-minneapolis-officers-booked-charged-in-killing-of-george-floyd/570984872/ [↩]

- Fatal force: Police shootings database. (2020). The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/investigations/police-shootings-database/ [↩]

- Davis, A. J. (2017). Policing the Black man: Arrest, prosecution, and imprisonment. Pantheon. [↩]

- Kilgo, D. K., & Harlow, S. (2019). Protests, media coverage, and a hierarchy of social struggle. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 24(4), 508-530. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161219853517 [↩]

- Lamb, Y. R., & Byerly, C. M. (2019). Kerner @ 50 looking forward; looking back. Howard Journal of Communications, 30(4), 317–331. https://doi.org/10.1080/10646175.2019.1627959 [↩]

- Grieco, E. (2018, November 2). Newsrooms employees are less diverse than U.S. workers overall. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/11/02/newsroom-employees-are-less-diverse-than-u-s-workers-overall/ [↩]

- “Media trust” was measured by having participants rate their level of agreement or disagreement on a 1 to 7 scale with 7 being more agreement regarding whether the following words or phrases describe the news media: “fair,” “biased,” “accurate,” “tells the whole story,” and “separates fact from fiction.” Answers for “biased” were reverse scored so a higher number indicated less bias, and then all five items were averaged together into a composite score (M = 3.2, SD = 1.2, Cronbach’s α = 0.87). [↩]

- A report released in September 2020 by the Armed Conflict Local & Event Data project (ACLED) found that of the 10,600 protests in the United States from May 24 to August 22, 95% were peaceful. Well over 80% of the total protests were related to either Black Lives Matter or COVID-19, the report said. ACLED is a non-profit disaggregated data collection, analysis, and crisis mapping project. https://acleddata.com/acleddatanew/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/ACLED_USDataReview_Sum2020_ SeptWebPDF_HiRes.pdf [↩]

- To figure out what statements best measured these concepts, we initially conducted a principal component analysis (PCA) with promax rotation using a scree plot test to determine what items loaded together as separate concepts. That analysis suggested three factors, two of which are described here. “Expectations of how the media should cover Black communities” was measured with ratings on a 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) scale to three statements that were then averaged together regarding what the news media should do. These were: “Should play a role in helping people understand racial injustice issues,” “Should play a role in breaking down barriers between people of different races,” and “Cover protests of racial injustice, such as the recent Black Lives Matter protests,” (M = 5.5, SD = 1.3, Cronbach’s α = 0.84). “Evaluations of how the media actually do cover Black communities” was measured with ratings on a 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) scale regarding what the news media actually do, using the following statements: “Do a good job at breaking down barriers between people of different races,” “Do a good job covering protests of racial injustice, such as the recent Black Lives Matter protests,” and “Do a good job helping people understand racial injustice issues.” In addition, participants rated on a 1 (very inaccurately) to 7 (very accurately) scale the following: “How accurately do the media portray black communities,” “How accurately do the media portray my community,” “How accurately do the media portray other communities of color,” and “How accurately do the media portray my personal interests.” All seven items were averaged together (M = 3.3, SD = 1.3, Cronbach’s α = 0.89). A paired t test showed that the mean for “How should the media cover Black communities” was significantly higher than the mean for “How does the media cover Black communities,” (t (1,051) = 40.71, p < .001). [↩]

- Based on the PCA explained above, “perception of newsroom diversity” did not load on any of the three factors, so it was measured as a single item by having people rate on a 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) scale their feelings about one statement: “Newsrooms are diverse” (M = 3.7, SD = 1.6). [↩]

- This was measured using the third factor in the PCA explained above. “General perceptions of the treatment of Black people in American society” was measured on a 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) scale in regard to two statements: “Black people have equal rights to white Americans” (M = 3.0, SD = 1.9) and “All things considered, it is good to be a Black person in the United States” (M = 4.0, SD = 1.7). While the PCA analysis showed these two statements loaded together as one factor, a Spearman- Brown test showed they were unreliable if averaged together, so they were kept as single items. [↩]

- This was tested using ordinary least squares (OLS) regression with “media trust” as the dependent variable, R2 = 0.52, Adjusted R2 = 0.51, F = 86.02, p < .001. “How does the media cover Black communities” (β = 0.64, p < .001), “perception of newsroom diversity” (β = 0.09, p = .001), identifying as a Democrat or being liberal-leaning (β = 0.10, p < .001), and being older (β = 0.08, p = .001) all were significantly related to media trust. No other significant relationships were found. [↩]

- Grieco, 2018. [↩]

- A total of 1,123 survey responses were received, but data from 71 were not used because participants appeared to take the survey more than once (n = 21); did not indicate they were 18 or older (n = 10); did not indicate they were Black or African American (n = 7); used an invalid, duplicate, or no mTurk ID (n = 16), and did not finish most of the survey (n = 17). [↩]

- Participants were asked “Would you describe any part of your racial or ethnic identity as Black or African American?” and only those who selected “yes” were eligible to continue with the survey. [↩]