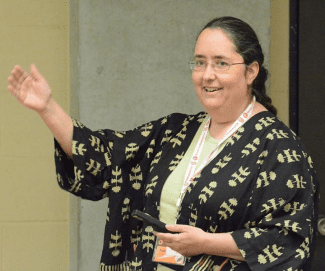

An Interview with Dr. Jean Goodwin

In less than a week, Dr. Jean Goodwin (North Carolina State University) will deliver a public lecture for the Media Ethics Initiative on the ethical issues in our communication and argument about climate change. Dr. Scott Stroud, MEI Director, sat down with Dr. Goodwin (virtually, of course, since we live the future at MEI) and found out more about her approach to rhetoric, communication, and ethics.

Stroud: Can you tell me a bit about your training and interests in communication? What got you into this line of work, and what are you interested in?

Goodwin: I was enjoying legal practice, but couldn’t figure out an institutional setting I was willing to put up with—staying with the bureaucracy at legal aid, working for a big firm, or hanging up my own shingle and spending half my time trying to squeeze money out of clients. I had had some courses in rhetoric as an undergrad, and had learned that rhetoric was creative, systematic, and argumentative. Cool! I was happy to find that there were actually PhD programs where you could study it.

Stroud: I see you’ve done some past work on classical rhetoric, including important figures such as Cicero. How did you get interested in that area? Why do you think classical rhetoric still matters to us today?

Goodwin: I fell into classical rhetoric partially by accident: when it was time for me to choose a dissertation topic, I had had at least one seminar a year on Cicero, so he was the rhetorician I knew the most much about! But this turned out to be a piece of good luck, since the highly agonistic politics of the Roman Republic provides useful perspectives on our own. Cicero had neither armies, high birth or exceptional wealth; to survive in political combat, he had only words. How did he make them work?

Stroud: What are some of your present research projects? What else are you involved in right now that may be of interest to those thinking about the intersection between ethics and communication?

Goodwin: There’s a fundamental question underlying all communication: Why does it work at all? Why should we pay attention to others’ messages, much less credit them? After all, junk mail gets tossed into the bin by the door. I have been collaborating with other colleagues in argumentation studies to examine precisely this question, focusing on civic controversies–situations where we expect disagreement and distrust to be widespread. Our research suggests that speakers establish themselves as trustworthy by making and living up to ethical commitments. In this sense, communication can only be effective if it is ethical.

Stroud: Some of your recent work focuses on science communication. What are some of the pressing ethical issues that those studying science communication should think more about?

Goodwin: Scientists often voice concern about the poor state of science communication. But being scientists, what they think they need are social scientific studies that document the effectiveness of specific communication techniques. In my view, communicators who set out to meddle with others’ minds are likely to be perceived as manipulative, and their messages rejected. (In fact, this is an ancient lesson, going back to Plato’s Gorgias.) Instead, I believe that scientists should be thinking much more about their ethical responsibilities–what they need to do to earn the trust of their fellow citizens.

Stroud: Specifically, I see that you’re thinking more about the choices that scientists may make in public deliberation over climate change’s causes and possible solutions. What are some of those ethical choices in the communication over climate change?

Goodwin: Scientists tend to be very aware of disagreement within their own fields. But when communicating with broader publics, they sometimes become less tolerant of differing views. While is is entirely appropriate for scientists to use their rights as citizens and advocate strongly for the single, correct answer, there are other roles that they can usefully play in public deliberations. Selecting among roles–advocate, advisor, reporter, educator–is the key ethical choice a scientist can make in climate communication.